ORLANDO, Fla. — What often gets lost in PGA Tour coverage, what you don’t see on TV, is what transpires from Monday to Wednesday. Three days of warming up, schmoozing, shooting the breeze. It’s prime time for media members seeking interviews, too. On these days, whenever I have a spare moment by the practice area, I find myself drawn to Bryson DeChambeau range sessions, arguably the most fascinating spectacle in golf.

On this occasion I come upon DeChambeau Wednesday mid-afternoon at Bay Hill, doing work after his pro-am round. The movement of 90 percent of pros on the range is casual, languid, inscrutable. There’s none of that in Bryson. There was nothing casual on the range last June, when he hit balls past sunset on Saturday at the Memorial, the night before he won the event. He was hardly inscrutable during a complete range meltdown at the British Open. He has said he’d have to “shoot 54” to skip a range session after a round.

Even Wednesday, when he’d made some time to mess around with Bubba Watson, he had a purpose: watching the FlightScope numbers of intentional shanks, plus mastering this ridiculous trick shot. Now, as DeChambeau pounds wedge after wedge, there is still nothing casual. He lifts the club up to his eyes to study the face and shakes his head.

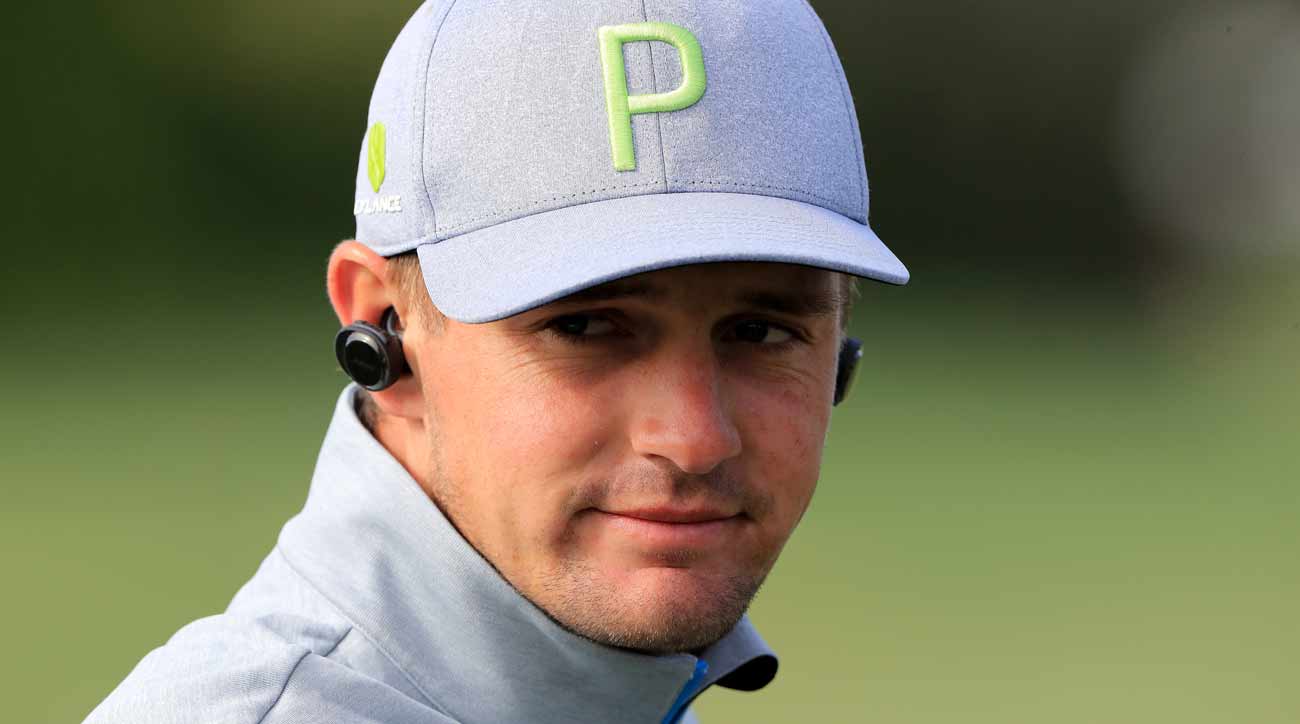

Steve Stricker, the presiding U.S. Ryder Cup captain, is hitting balls directly to his left, accompanied by his caddie (and wife) Nicki Tiziani. Bryson’s caddie Tim Tucker stands guard over his bag, a large white Puma-branded number that’s custom-decorated with Arnold Palmer’s umbrellas for the week. Behind Tucker and Bryson are three men wearing FlightScope apparel and checking his numbers, plus two more wearing Sik hats (his putter company). His agent Brett Falkoff is also there. Media members pop by, drawn in by the same gravity that compelled me here, and each time a pro-am group passes by, they, too, stop and gawk. A DeChambeau range sesh is different.

He is wearing a set of black earpieces; it’s not clear if he’s listening to anything. Perhaps the buds factor into his extensive brain-training regimen (which involves, among other things, watching Deadpool while hooked up to a machine that will automatically stop the movie if his brain’s electrical current gets too active).

DeChambeau’s swing is a puzzle he is forever unriddling. After one particularly dissatisfactory effort, he turns to Stricker. The issue at hand: Grass direction after impact from an iron shot. Does the grass go down into the ground? Or is it pressed forward, obstructing the contact between ball and club? The matter isn’t quickly resolved.

As they continue to hit balls, the conversation continues. It’s mostly DeChambeau jabbering, with an occasional response from Stricker. Other members of the crew lob in thoughts and observations. “That material needs somewhere to go,” Bryson says, returning to the dirt-grass dilemma. When he’s thinking hard, you can see it. “There needs to be, like, a cut-out. What if you put a ‘V’ at the bottom of the face?” He gestures toward the bottom of the club’s sweet spot.

It’s hard to imagine another Tour player trying to invent a new club technology on the eve of a tournament start. Stricker grabs one of DeChambeau’s clubs. Tucker, Bryson’s caddie, takes a photo of Stricker’s wedge. Another of Bryson’s tribe films Stricker’s swing, which is presented to the young scientist for inspection. DeChambeau borrows Stricker’s nine-iron. Constant motion, evaluation, reconsideration.

After just two swings of the nine-iron, another lightbulb goes off. Bryson says he has to hit down too hard on his short irons to make proper contact. Yet with this motion, something about the bounce of the club suits him. He’s trying to figure out why.

“If too much bounce is making it dig,” he murmurs. “Then not enough bounce — I haven’t tried that, I don’t know what that does.” He shakes his head. “If this really is just a bounce thing, I never thought about going the other way…”

This thought trails off, but he’s satisfied, for now, with this new bit of information, and thanks Stricker for the consult. As Stricker heads to the chipping green, I ask what that was all like. He laughs.

“Well, it’s different, huh? We were talking about the same stuff, but we’re doing it in different languages.” He’s interrupted by a young fan shouting for his autograph. “Sorry,” he tells me. He signs a couple autographs, but keeps walking as a few older fans begin to head his way. “Sorry,” he tells them, gesturing toward the chipping area. It strikes me that pros must spend a lot of time apologizing — the polite ones, anyway.

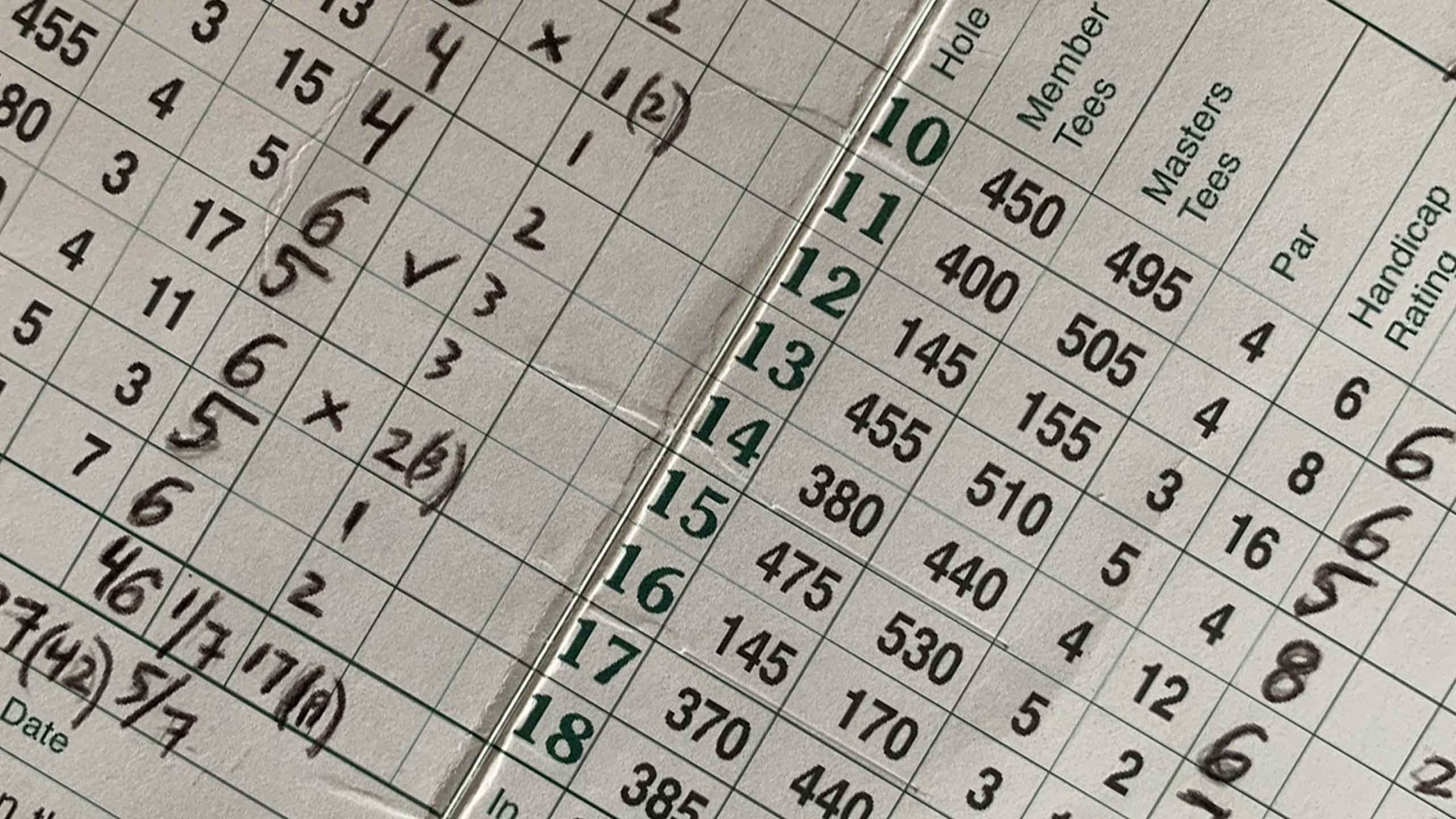

Stricker explains that DeChambeau has been noticing wild fluctuations in the spin rates of his short irons, so he wanted Stricker to hit some of his clubs and vice versa.

“He’s an intelligent guy and you can see he thinks all of this stuff through. He wants it his way, and that’s good in this game. He believes so much in what he’s doing,” Stricker says. “And he’s onto something there, by the way. Because when he hit my wedge, the spin rates were all the same. You could hear it. With his, it was all over the place. So it was either the bounce, or the lie angle, or something.”

Now DeChambeau is coming down to the practice green, flanked by the men in Sik hats. Does he have a minute to talk bounce with a reporter? He says he does — just not right now. He’s setting up another putting machine, different from the one he used Tuesday.

“I have to get this done before the sun comes down,” he says. “Er, when the dark comes up. Whatever.” He laughs.

It’s 3:46 p.m., three hours before nightfall.