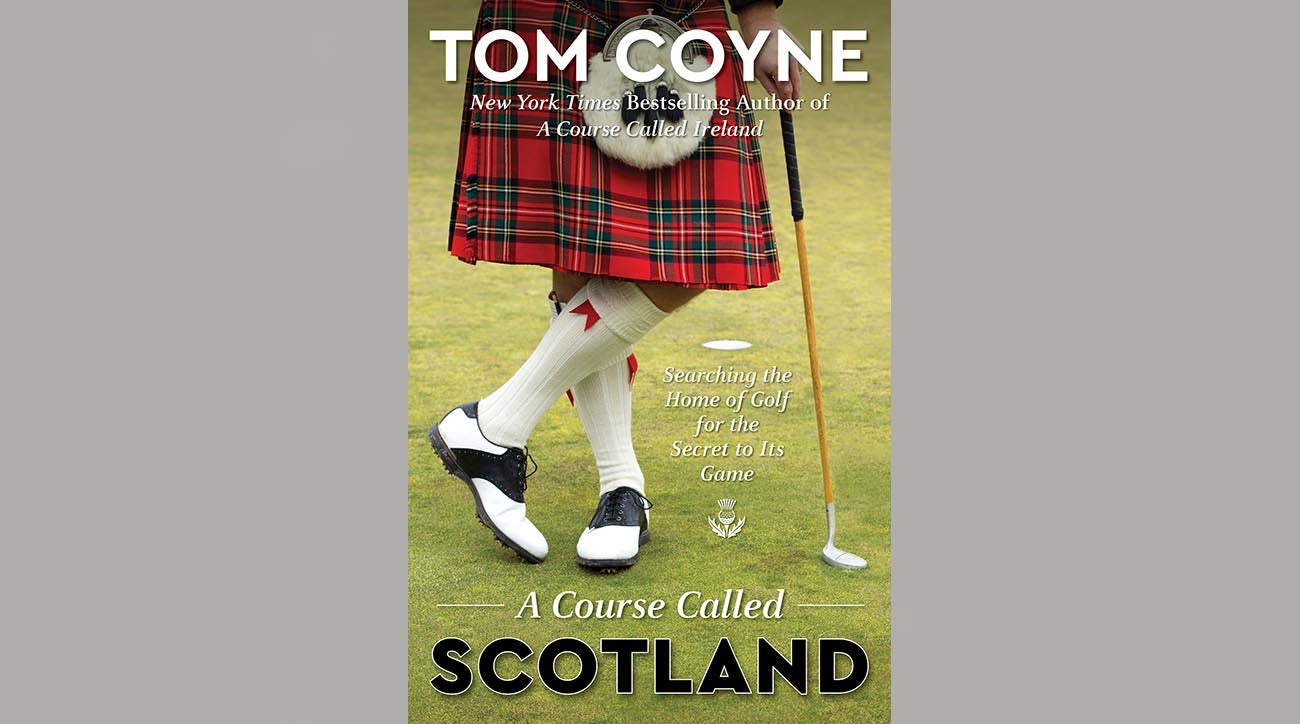

Tom Coyne isn’t afraid to play a little golf. The author of several golf tomes, including the best-seller A Gentleman’s Game, is back with his latest work, A Course Called Scotland, which chronicles his adventures (and aches and pains) from 111 rounds over 57 days in Scotland. Coyne hits the headliners, like the Old Course at St. Andrews, but also ventures far off the beaten path. In the section excerpted below, he visits Carnoustie, site of the 2018 British Open. You can order the book here.

On my list of many courses, there was only one whose name conjured actual fear. Perhaps the panic came from the 1999 bloodbath of an Open Championship, when the links famously left a poor Frenchman barefoot in a burn, and where the winner’s score of six over was a throwback to the days of hickory-shafted champions. But if you gave most golfers a free-association test and threw them the word “Carnoustie,” the flinch responses would be “Hard,” or “Really hard,” or perhaps, as the locals called it, “Car-Nasty.”

When I told Dad that the last round of his week in Scotland would be at the site of Jean van de Velde’s unwatchable collapse, I could see the apprehension in his eyes as he gazed off into the distance and nodded, whispering “Carnoustie” with the look of a willing but outnumbered soldier.

In case you missed it—and you’re lucky if you did—in 1999, the French pro brought a three-stroke lead to the final hole, prompting the Claret Jug engraver to begin etching his name into the trophy. He would soon go hunting for sandpaper as van de Velde knocked his ball around the grandstands, taking off his shoes and standing in a stream to contemplate a water blast, and eventually getting up and down out of the sand for a triple bogey that led to a playoff he would lose to Scotsman Paul Lawrie. Sadly for Lawrie, few remember that his record-setting ten-shot comeback on the final day was one of the greatest feats in golf; it would forever be overshadowed by one of the most tragic.

Some might remember Carnoustie for the Irish pride of Pádraig Harrington’s breakthrough win in 2007, or the birth of Tom Watson’s links love affair in 1975, or Ben Hogan’s victory during his only trip to the UK, where his gutsy play on number six between death bunkers and out-of-bounds led to the hole being named “Hogan’s Alley.” But most of us recall watching golf on a Sunday morning back in the 1990s and feeling that sick excitement the Romans must have felt in the Colosseum as lions had their lunch. For all the pain and empathy, I remember feeling a tinge of relief as well—golf was hard for everyone, it turned out, and it could embarrass us all.

I expected to find black clouds swirling above a haunted clubhouse, with a soundtrack of grim organ music and a staff dressed in funeral colors. But there were no hearses queued up in the parking lot at Carnoustie; rather, it was a bright and cheery place with a modern clubhouse and a laughing starter eager for us to have a great day. Like St. Andrews, the course was a true municipal track shared by six golf clubs, and the spirit of welcome was palpable, most notably in our sage caddie, Steve, who came along to carry for my father.

In his early thirties, Steve was wrapped up in wind gear and tattered hiking boots with a cigarette held in his teeth, but I could tell before shaking his hand that he was a player moonlighting as a looper. I had learned to spot the sticks over the years; it was their comfort on the course, combined with the sinewy frame of someone who spent more on tournament entries than on meals. Steve had that lean, unshaven, unimpressed look of a person who golfed with his rent check and for whom an Open venue was his natural setting. For Steve, it actually was—he had grown up on the Carnoustie links and played on professional tours around the world. He was a journeyman on hiatus, making a few pounds and visiting his family before plotting his next season on the minitours. Maybe it was the way he skillfully lit his cigarette in a thirty-mile-per-hour wind or how he didn’t flinch at Dad’s mishits, but his was the look of a golfing creature, and this was his living room, while I too often felt like I was crashing in somebody else’s. I wanted that look and that feeling. I wasn’t going to leave Carnoustie without asking him how he’d gotten it.

Dad played steady golf around Car-Nasty, knocking low and short shots along the fairway but keeping his ball in play and out of the bunkers. Steve coached him around with enthusiasm and good humor, handing my dad the 4-wood without his having to ask for it and reading the requisite two inches of wind into Dad’s putts. On the sixth green, Steve knelt down behind Dad’s ball and confidently declared, “Two cups outside left.” When Dad missed left by a good four feet, Steve explained, “I didn’t say two Stanley Cups.”

Perhaps it was my pent-up Carnoustie anxiety, but I played my nines by a flip-flopped script. The back nine and the final five holes were supposed to be the card-wreckers, but I played them in one over par, making the four on the final hole that van de Velde had so needed, and I parred the 446-yard tenth that had the best name on the card. It was called South America, and Steve explained that its curious moniker came from a clubhouse party many years before. A local lad was shipping off to seek his fortunes in South America, so they celebrated him with a proper sendoff, at which most of the Scotch in Scotland was consumed. The merriment inspired him to set out on his trek to South America that very evening, and when he was found asleep near the tenth hole the next morning, the name of his destination stuck.

I flailed my way through the front nine, where I attempted to play down Hogan’s Alley on six but instead blazed a new path down Coyne’s Crumbling Sidewalk, sampling a medley of bunkers on my way to double bogey. I feared I wasn’t going to be able to summon the courage to ask Steve about the secrets to his game, not after a front-side 44; surely he would dismiss me with a charitable “Keep your head down, and keep swinging.” But after navigating my ball safely over the famed Spectacles on fourteen in two shots (the two side-by-side bunkers that gobbled approaches on the par 5 resembled spectacles if you missed them but looked more like giant sheep balls if you didn’t), my confidence was buoyed. I managed a par on the 245-yard sixteenth, a hole Watson called the hardest par 3 in golf, and I somehow kept my ball out of the snaking Barry Burn on seventeen and eighteen, both played into a wind that doubled their already punishing length. The looping burn plagued the closing holes and seemed to defy the rules of nature—water was not meant to flow in nine directions at once, and Bernard Darwin had aptly described the stream as “the ubiquitous circumbendibus.” As we approached the finish I closed with a string of hard-fought pars, so I sidled up to Steve and asked him what was going through his mind when he was playing his best.

“I don’t know. I’m not thinking about much, really. I’m just thinking about going low. If I’m swinging well, that’s it—just go low.”

Just go low. Easy enough. I should have expected an unsatisfying answer to such an obvious question. I already knew that when you were playing well, your head was mostly empty. But Steve did elaborate after a drag.

“In a tournament, I’m just thinking about fundamentals. I’m thinking about using what’s working on that day. Every day, your makeup is different.

Your nerves, your muscles, your head—it’s always different. You can’t change it. So you go with what you have on the day. Stay on your fundamentals, use the shot you have with you, and make birdies.”

I was interested to hear him hint at acceptance and not forcing a game you didn’t bring with you. His keys might have seemed overly plain, but as with all grand mysteries, the answers were wrapped in simplicity. The player’s mind-set was not one of Go pretty good or Go to not shame yourself or Go look good or Go make the right swing or Go find that backswing position you’ve been working on with your coach for a year but can’t quite find this morning or Go make them think you can play or Go so they’ll say generous things; rather, it was go to one place, and f— everywhere else: Go low.

Steve also shared that he would not have played golf today. He was glad he was caddying, because playing in wind like this had wrecked his swing in the past.

“My coach tells me to take two days off if I play in bad wind. You start making swings in this stuff that you need to forget about. You can learn a bad way.”

I understood what he was telling me, and it hit a vulnerable spot. I didn’t have the luxury of two days, let alone two hours to put down the clubs, and I could feel how this week’s tempest had left my swing feeling like I was throwing wild haymakers at my golf ball. With a little more than a month to go, I’d expected my links moves to be thoroughly grooved by now, but there was nothing groovy about punchy stabs at a wobbly golf ball.

Acceptance, he said. Well, the wind would have to change, because my itinerary wouldn’t. I was sticking with the plan that brought me here, and I was trusting the powers that had me completing Carnoustie with my eighty-one-year-old father, who had just finished the toughest closing stretch in golf in a wind that would have kept a Tour player indoors, and neither one of us took off our shoes even once. Who knew—maybe the wind would be blowing fifty miles per hour at Bruntsfield. If it was, I would have to find a bookmaker and double all bets.

A Course Called Scotland is Tom Coyne’s fourth book. He lives in Philadelphia with his wife and two daughters, and is an associate professor of English at St. Joseph’s University. Learn more about Tom on his website.