At the time of his death, Arnold Palmer had an estimated 14,000 golf clubs, including 2,500 putters, but since then the number of clubs in his estate has grown. That’s because the R&D people at Callaway and a good number of basement inventors across the world already had equipment en route to Palmer at the time of his death last Sept. 25.

Palmer was a rare blend of personality types, some of them conflicting. In dress and manner he was conservative. (He once gave me two of his old-school hard-collar shirts from his massive stockpile; fearful that the shirts would stop being manufactured, he had loaded up.) But in all things mechanical, he loved innovation. Palmer was, and no one would say this is common, a sentimental person who had little attachment to objects. Yet he could not throw things away. As the elder of his two daughters, Peg Palmer, said recently, “In western Pennsylvania, the attitude is, ‘Never know when you might need that.'” Hence, the 14,000 clubs.

Palmer owned three houses on the fringes of the Latrobe Country Club, ostensible real-estate investments that over the years became depositories for his ever-growing club collection. Kitchens, living rooms and bedrooms were lined with clubs. More recently, the majority of the equipment was moved to an enormous warehouse on the outskirts of the course. Walking its Walmart-like aisles is like being in a museum devoted to club manufacturing, circa 1940 to the present.

Palmer’s estate managers, under the guidance of veteran IMG executive Alastair Johnston, would like to identify what clubs have particular significance. For instance, they hope to determine which clubs Palmer used in his seven major titles and other significant victories, like his 1981 U.S. Senior Open win. Wish them luck. As Hall of Famer Bob Goalby recently noted while discussing Palmer’s win at the 1962 Colonial, “He used four sets of irons! And I’m not making that up.” Who knows what was in the bag for the fifth round, an 18-hole playoff.

“Arnold was probably the first guy to say, ‘It’s not me—it’s the clubs,” says Goalby, the 1968 Masters champ. There’s a lot to be said for that attitude, especially when you are the best player in the world, or one of them. Palmer’s approach could be called an early version of what sports psychologists today call self affirmation. Peg Palmer calls it part of her father’s “magical thinking,” which she believes explains much of his success. What U.S. Open contender would want to reinvent his game, and question his talent, on the basis of shooting one round of 75? In his prime, Palmer had two club-repair guys in downtown Augusta—one was a retired U.S. Army colonel, Bernie Porter—he would visit regularly during the Masters for post-round club-tweaking. The colonel watched. Arnold did his own tinkering.

“Arnold could travel with a lot of clubs because he had his own plane,” says Goalby. He paints the scene on the tarmac in Latrobe. “I flew with him some. You’d see him put his bag in, loaded with clubs. Then his co-pilot, he’d be carrying a bunch of clubs too. Arnold would waggle the clubs on the tarmac. `Let’s bring this one. Let’s bring this one.'” It didn’t sound like many got left behind.

“[Ben] Hogan, see, he was nothing like that,” Goalby says. “I was paired with Hogan for the first two rounds of a tournament, and I switched out my irons between rounds. Hogan makes some comment to me about it and then when he’s teeing up his shot he says, `I need eight years just to break in a new set of irons.'” Goalby’s point is that Palmer and Hogan approached the issue of commissioning clubs for their bags in wholly different ways. Not surprisingly, the Hogan-Palmer relationship was famously frosty.

If Palmer’s co-pilot was carrying audition clubs, you can imagine what his caddies had to haul. It was a common sight at tournaments to see Palmer carrying five or more clubs on his way to the practice tee while his caddie lugged a bag stuffed with maybe 18 more. Palmer, naturally, would only carry 14 clubs for the tournament, but in practice rounds he would sometimes ask friends in the gallery to retrieve clubs from the locker room on his way to, say, the 2nd green.

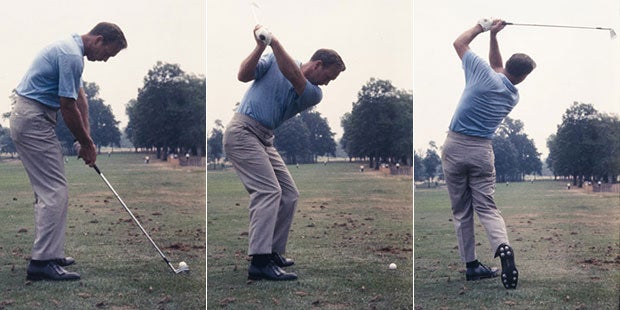

For decades, visitors to Latrobe Country Club or Bay Hill would see Palmer’s cart near the clubhouse with two big bags strapped on the back, with 15 to 20 clubs in each one, plus a collection of putters on the seat. I’ve had the pleasure of being with Palmer on the Bay Hill range, and on one occasion he handed me a driver out of his bag and said, “Give this a try.” Its black head was the size of softball and whether it was legal or not I could not say, but my shots with it were uncommonly long. Palmer, who in his prime was one of the longest, straightest drivers the game has ever seen, was like every other golfer who has ever played: He wanted a driver that would give him extra distance and a putter that would hole more putts. At tournaments, Palmer often went to the practice green with three or four putters. At Bay Hill, that could be a mere starting point.

His modest garage at his home in Latrobe was for years chiefly a workshop for club repair and tweaking, as was his garage at his condo at Bay Hill. Neither could accommodate a car.

The Latrobe workshop was also a de facto meditation studio. It was a place where Palmer could be alone, or with others, in silence, and work out issues that went far beyond the pressing problems facing his clubs. But the Bay Hill garage-workshop was not a temple for anything except club gossip, dinner plans and story-telling. Beers came out of a small refrigerator at 5 p.m. sharp for Palmer, his close friend Dow Finsterwald, golf-course architect Ed Seay, Palmer’s son-in-law Roy Saunders and anyone else who happened to be around.

Later, when Palmer built a one-story office complex at Latrobe beside his house, it included a large workshop. (“When I get pissed off at everybody, I come in here and work on the clubs,” he once told me.) At the time of his death, the workshop had hundreds of clubs in it, and every tool a repair buff could possibly need—pliers, files, vices, screwdrivers, various grades of sandpaper—plus dozens of cans of spray paint, lacquer and varnish. Players from Palmer’s era jokingly talk about how Palmer would “butcher” beautiful drivers and fairway woods in the name of improvement. Palmer was devoted to function, not form. That and putting his personal stamp on his equipment, making each club his own.

Palmer’s longtime aide de camp, Doc Giffin, saw him operate on hundreds of clubs over their half-century together. “He just loved to tinker,” Giffin says. “He had an obsessive search for the perfect club. He felt that a perfect club might produce perfect shots.” It was a quest that occupied him nearly to his dying day. “He was also a big believer in changing grips, especially putter grips,” Giffin says. “He put a lot of stock in that.”

For decades, Palmer insisted on changing the traditional wrapped leather grips himself. Then about 20 years ago, he trained one of his former caddies, Cori Britt, who was then working in Palmer’s office, to grip his boss’s clubs and eventually to assemble clubs using components sent by Callaway. Palmer liked Britt’s attention to detail and, after Britt graduated from college, had him work in his club-manufacturing business. Today Britt is a vice president of Arnold Palmer Enterprises in charge of brand management. Palmer believed you could tell a lot about a man by his ability to bend a wedge.

Palmer played Wilson clubs as an amateur, and when he turned pro in 1954 he joined the Wilson staff. He continued to play Wilson exclusively until 1963, when he founded his own club-manufacturing company, the Arnold Palmer Golf Club Company. His ownership of that company didn’t prevent him from signing endorsement contracts, including deals with Dunlop and, yes, Sears. That might be difficult to imagine today, but Sears found that most anything with Palmer’s name on it would sell.

In 1999, Palmer disbanded his various club-manufacturing businesses, which never became a major force in the game. (Hogan’s business enjoyed far greater prominence.) Johnston, the IMG executive, explains Palmer’s struggles as a manufacturer by saying that his prime interest in equipment was making clubs for himself. The club needs of ordinary golfers were less apparent to him. Giffin says that about the most concrete club advice he ever received from Palmer was to put lightweight “senior” graphite shafts in his clubs. (Palmer knew slow clubhead speed when he saw it.) After his company disbanded, Palmer signed an endorsement contract with Callaway, and he remained with the company for the rest of his life. But on any given day, you’d see clubs from four or five manufacturers in his bag.

Palmer liked head-heavy clubs. He was devoted to the idea of taking weight out of the shaft and grip and adding weight to the head. He experimented with gripless clubs, but they never got traction, in any sense. He was an early adaptor of aluminum shafts, one of golf’s many passing fads. (They tended to snap, particularly in cold weather.) In fact, he became for first player on Tour to win with aluminum, at the 1967 Los Angeles Open, in a period when virtually every touring pro was playing traditional heavy steel-shafted clubs. A western Pennsylvania guy forgoing steel shafts. That tells you a lot right there.

But Palmer was tradition-minded in certain aspects of club-design. For most of his career, he preferred blade putters, putters that were a distant cousin to Bobby Jones’s beloved Calamity Jane, putters that looked essentially like irons. He had a large collection of Wilson 8802s as well as a similar putter he (and later Callaway) manufactured, sometimes called The Original. These putters would have been at home in Walter Hagen’s bag. But you’ll never pin Palmer’s preferences down. Later in life he fell hard for the Odyssey 2-Ball putter, which looks more like an early model of the Starship Enterprise than a traditional design. As for broom-handle putters, he despised them from the day they first appeared. Palmer believed that keeping the hands together on the grip through the swing was fundamental to the game. He was an ardent supporter of the USGA’s ban on the anchored stroke, which became the law of the land in 2016.

But Palmer could be tough to pin down. In 2000 he endorsed, for recreational play, a Callaway driver called the ERC II that did not meet USGA requirements for face thinness. For a brief period in certain circles, there was a lot of noise and hurt feelings over that endorsement. But Palmer’s point was that golf was meant to be fun and that the ERC driver would make golf more fun for more people. He had a huge fun-meter when it came to clubs. When he signed with Callaway, he went to the company’s southern California testing center, had himself a big time trying various clubs, and was surprised to learn that he wasn’t hitting the big, modern titanium-headed driver the correct way. He was catching the ball on the downswing, as he had done in his prime with wooden drivers. The new drivers, he was told, had to be struck slightly on the upswing.

One of the club lines Palmer started, Peerless Golf, was not noted for its esthetic beauty. The Peerless blade irons had almost no offset and looked hard to hit. (The shaft, hosel and heel of the club formed nearly a straight line.) They had a high pointy toe. (Palmer spoke often about “the lines of a club.” In club design he was drawn to lines and not curves.) Some Peerless irons had an odd, tiny wing hanging off the hosel. But there’s no evidence that feature, or the club in general, helped ordinary players. Peerless woods and irons are well-represented on eBay, at prices that do not suggest they are collectors’ items. For instance, a set of Peerless irons, two-iron through pitching wedge, was offered recently on the auction website for $27.88. Palmer’s interest in clubs was really about his interest in his clubs.

Peg Palmer says that some of the best times of her life with her father came while sitting on stools with him in his Latrobe workshop. “He might be putting a piece of lead tape on a club but thinking about when he has used that club and where he might use it again,” she says. “It was a ritual. He’d put on a piece of tape. Waggle it. Put on another piece. Waggle it.” Maybe take off half a piece. Refine, refine, refine. Along the way, Peg says, her father was developing a relationship with an inanimate object. There is much less of that among Tour players today as club-making has become far more mechanized and clubs can be reproduced almost exactly. “He put the time into his clubs because he loved doing it—he was a man who did what he loved,” Peg says.

“My dad was a manly man, kind of macho, kind of a chauvinist, but he was also a very creative person. The workshop gave him a chance to be creative,” she says. “It wasn’t mindless repetition. It was part of a process. He was at his most focused, his most engaged, his most peaceful, when he was in the workshop. It was a tonic for him. He liked seeing sparks fly, he liked all the stimuli of the workshop.

“Working on the clubs also kept him in touch with his working-class roots. I think my dad really celebrated the working class, and he felt connected to people who did things for themselves, as he did. That helped him be the architect of his own destiny. Doing things with his own tools, with his own hands, that was part of his identity.”

Peg Palmer is not enamored of every product to which her father attached his sturdy name, and his sturdy signature. Particularly, she says, those products loaded with high fructose corn syrup. But it’s a source of great pride for her every time—at yard sales, in sporting good stores, in her father’s workshops—she sees clubs stamped with her father’s name, the 12 cursive letters familiar to generations of golf fans. Palmer had the gift of a rhythmic name, with two perfectly balanced syllables before and after the 50-yard line: Arnold/Palmer. How many clubs around the world carry that name? North of a million. How many clubs did Palmer put in his meaty hands over the course of his 87 years? An incalculable number, but in the thousands.

Whatever that total is, I made one contribution to it. Years ago I gave Palmer a chipping-utility club I had designed. Arnold gave the E-Club a greenside workout in silence and said, “I like your club. There’s only one problem with it.”

“What’s that?” I asked. My heart was racing. I knew it was a USGA conforming club, so that wasn’t the issue.

“What club are you gonna take out of your bag to make room for it?”

The game’s 14-club rule saved Palmer from his own instincts and gave him a polite way to say nice try to any number of basement inventors. I like to think that Arnold held on to the club I brought him. He probably did. He didn’t part with much.

“Daddy liked bigger, better, faster,” Peg told me near the end of a long conversation about her father and his clubs. “He appreciated classic things but what really excited him was innovation.”

That makes total sense. Innovation offers the promise of improvement, and that, above all, is the game’s central tenet, the thing that keeps us coming back. Nobody understood that better than Arnold.

[gallery:13802243]