Arnold Palmer wasn’t a great athlete because he could hit a golf ball farther than his competitors. He wasn’t a great athlete because he collected 62 victories, including seven major titles, on the PGA Tour. And he wasn’t a great athlete because his accomplishments ushered in an era of unprecedented growth and prosperity for the sport and its professionals. Palmer was a great athlete because he defied expectations. When glory beckoned, Palmer would “go for broke,” as he liked to say. And when he went, it wasn’t just for him. It was also for us.

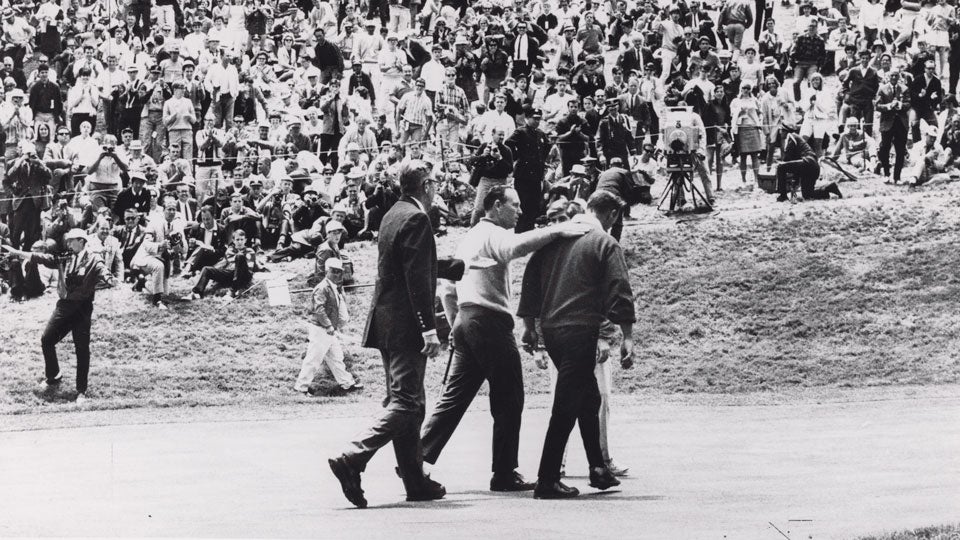

In 1963, Palmer was stalking the lead in the U.S. Open at Brookline. Four grueling rounds had failed to produce a winner, so Palmer, Jacky Cupit and Julius Boros embarked on an 18-hole playoff for the hardware. After 10 holes, Arnie trailed Boros by four shots, the early deficit foreshadowing a charge.

Palmer hooked his tee shot on the 11th hole and found his ball nestled in a rotten tree stump left of the fairway. He had three choices: take a penalty drop, hit another tee shot, or try to win his seventh major. Palmer pulled a 4-iron. He hacked once, twice, three times before lumberjacking his way back onto the fairway en route to an agonizing 7 that handed the national championship to Boros. Palmer had lost, and lost badly, and he later identified the culprit.

“Once again my bold style of play had mortally wounded me,” he wrote of the episode in A Golfer’s Life. “And frankly, it hurt like hell.”

MORE: Buy Sports Illustrated’s Arnold Palmer Commemorative

As thrilling as the wins were in Palmer’s Hall of Fame career, his defeats could be stinging—sometimes devastating. His was a high-wire act without a safety net, an exhibition of wild tee shots and daring approaches and putts struck so hard that they might run off the green—but at least, by golly, they wouldn’t fall short. Palmer freely admitted that the same brand of high-risk, high-reward golf that helped him win seven majors probably cost him at least seven more, but he was also keenly aware that even his failures had helped feed his legend.

“Perhaps the reason people enjoyed watching me play so much was that they could relate to my predicament,” Palmer wrote. “I was often where they were as I came down the stretch—in the rough, in the trees, or up the creek.”

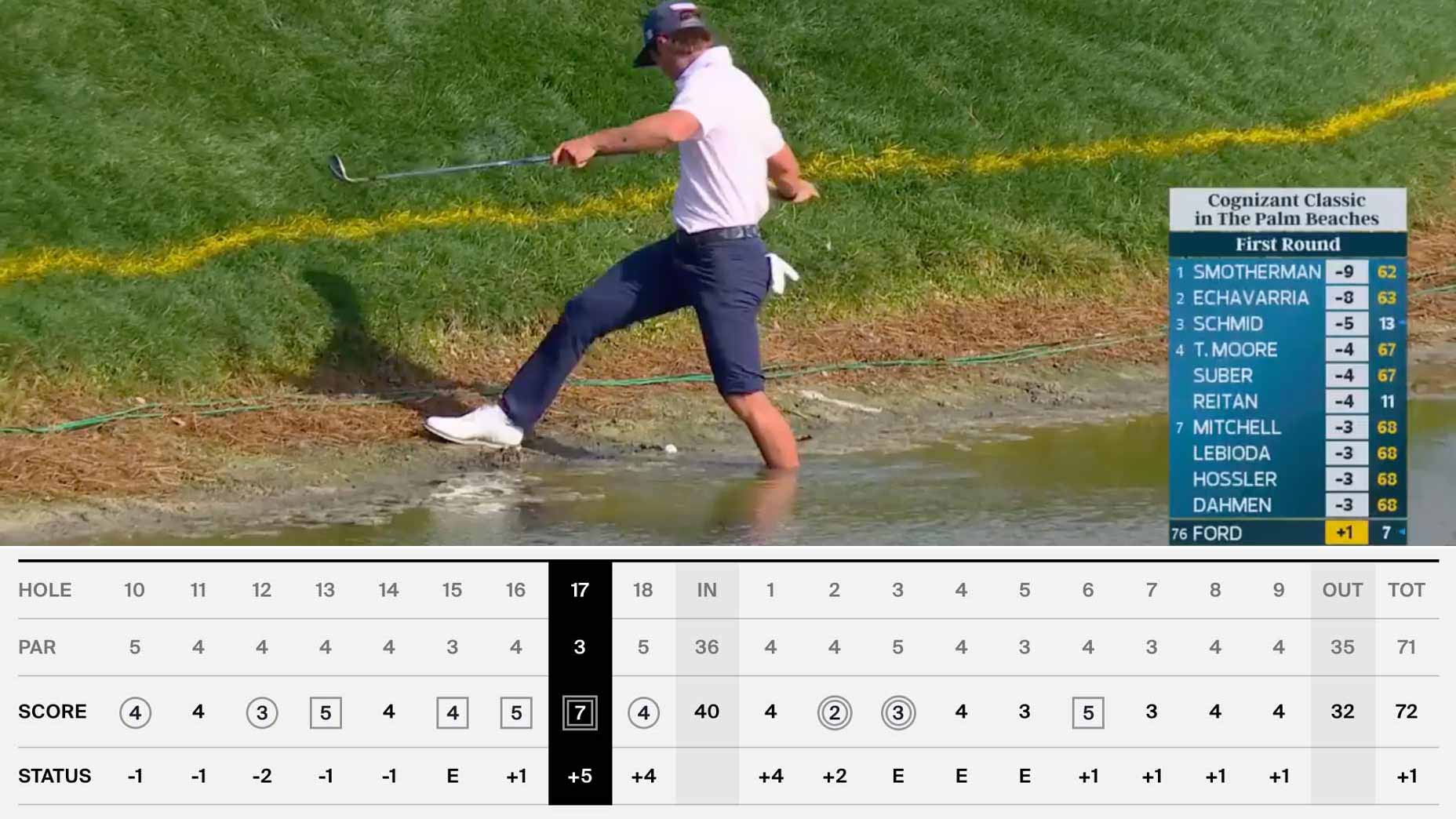

Rae’s Creek at Augusta National would introduce Palmer to major heartbreak in 1959. The defending Masters champion was eyeing back-to-back wins—until he splashed his tee shot on the 12th hole. Palmer avenged that loss at Augusta in 1960, but his collapse at the 1961 Masters made him cringe even decades later. Needing to par the final hole to preserve a one-shot lead, Palmer decided to accept congratulations from a friend in the gallery while assessing his second shot from the fairway, a blunder that he claimed “completely destroyed [his] concentration.” The ensuing double-bogey left Palmer with the honor of helping his rival Gary Player into his first green jacket.

He suffered near misses in both the Open Championship (which dashed his hopes for the calendar year Grand Slam in 1960) and the PGA Championship (which remained the only major missing from his career Grand Slam résumé). Yet the loss that left the most scar tissue and ultimately epitomized the extreme highs and lows of Palmer’s career was his epic implosion at the 1966 U.S. Open.

Enjoying a seven-stroke cushion as he made the final-round turn at the Olympic Club, Palmer set his sights on a new target. He was within striking distance of Ben Hogan’s four-round U.S. Open scoring record, and since he had all but secured his eighth major title, why not make history, too? Palmer even took a moment to reassure a nervous Billy Casper, his closest competitor, that the runner-up finish was his to lose.

“Don’t worry, Bill,” Palmer said. “You’ll finish second.”

A pair of quick bogeys on the 11th and 13th holes ended Palmer’s hopes of erasing Hogan’s mark and breathed new life into Casper, who’d won the 1959 U.S. Open at Winged Foot. Irked by what he perceived as “safe” play by Casper, Palmer grew bolder—and much more erratic. He bogeyed 15. And 16. And 17. His lead disappeared. Palmer salvaged par on 18 to force a playoff the following day, when Casper put Palmer out of his misery, beating him handily by four strokes. Casper was only chasing a trophy. Palmer was chasing a ghost.

According to Doc Giffin, who’s been managing Palmer’s affairs since 1966, his boss never got over those losses at the 1961 Masters or the 1966 U.S. Open. Still, even behind closed doors, disappointment never morphed into bitterness.

“He bounced back quick,” Giffin said. “He was a strong man. He didn’t let things get him down. Things could make him angry, but they didn’t depress him.”

Maybe Palmer seethed only on the inside, as golf etiquette demands. Maybe Palmer, who lived surrounded by family and friends, enjoyed too much support to fall into deep despair. Or maybe Palmer, who once lost his best friend in a car accident, was well-attuned to the difference between on-course disaster and real-life tragedy.

Or maybe Palmer the man had retained something of the boy in him. Once, while playing in an amateur tournament, young Arnie found his tee shot deep in the woods. Rather than pitching back to the safety of the fairway, he decided to attack the green—right through the trees. “For the first time, there was a little gallery following me, and I remember how enthusiastically they cheered that shot,” Palmer wrote. “Their response genuinely surprised me. They loved it…and so did I…I had it within my grasp to please people I didn’t even know with my golfing skills! What a thrill!”

The rewards, for him and for us, would be well worth the risks.