For a glimpse of what’s in store for golf fans in this country who like to have a little extra rooting interest, we take you to a ground-floor office in a bland business complex, four miles west of the Las Vegas Strip.

It’s approaching noon on a Friday. Five televisions on the wall are screening live feeds of the second round of the 2018 Players Championship. On one, Bubba Watson, wielding his pink driver, sails his tee shot on the first hole deep into the trees.

“He’s an underdog to make par here,” Martin de Knijff says.

An intense but amiable man in his mid-40s, with a dark goatee and a gleaming pate, he is watching the broadcast from behind a conference table, flanked to his right by three colleagues at computers.

“Put him at plus-one-twenty,” de Knijff says.

A coworker clacks a keyboard, and on one of the TVs, up pop those odds, alongside Golf Channel’s coverage of the hunt for Bubba’s ball.

“Let’s see what kind of lie he has,” de Knijff says. “Maybe I should have made him an even bigger ‘dog.”

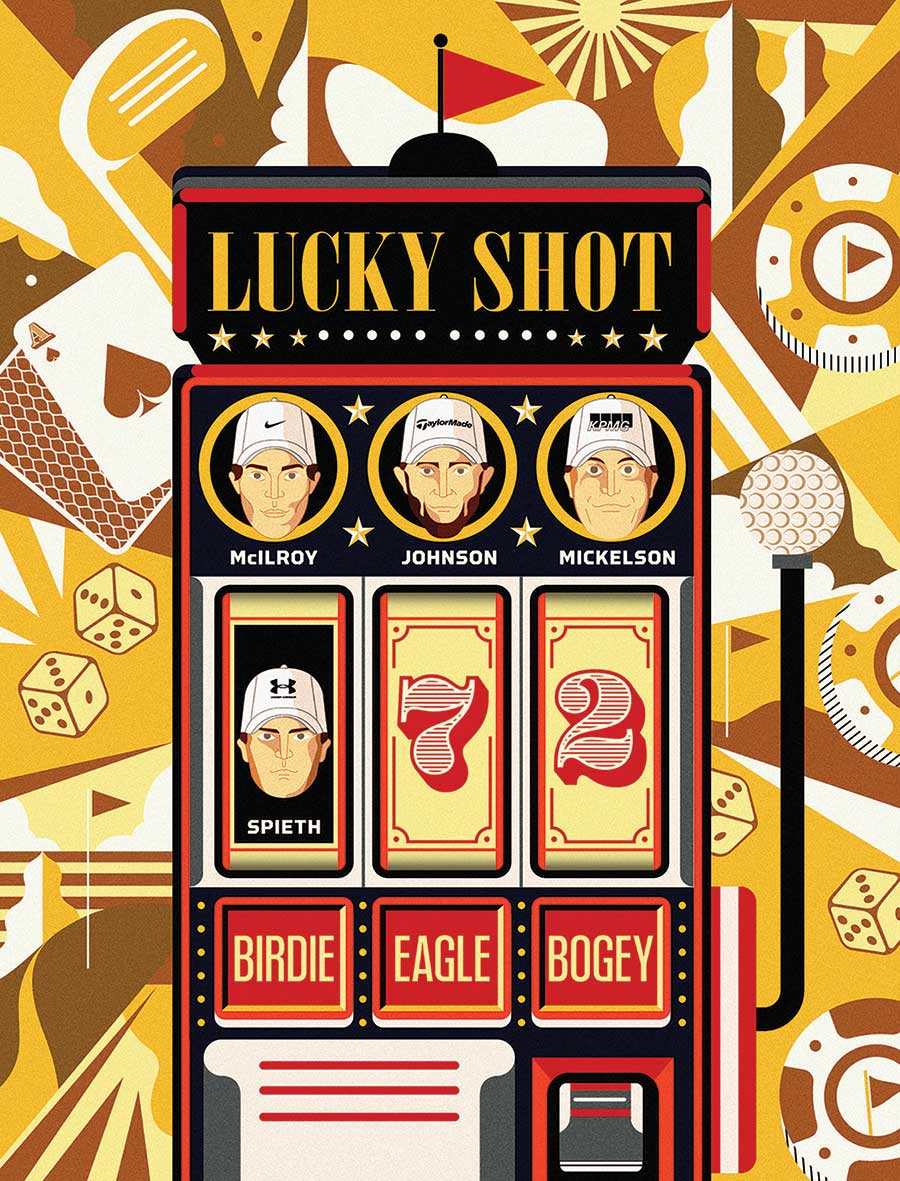

A few months from now, being right about such things will really matter. But this is just a test, a trial run of a digital gaming service that de Knijff (pronounced Kn-AYF) plans to launch in the United States this fall. He calls it “SuperLive” betting, and as the name suggests, immediacy is key to its appeal. Instead of setting odds on, say, Bubba to win the Players, or to shoot a lower second-round score than Jordan Spieth, or to best Billy Horschel in the event, the system churns out probabilities on Bubba’s prospects, shot by shot. It does so simultaneously for multiple players in headline groups, whipping up a storm of mid-tournament gambling action.

De Knijff knows there is a market for this kind of wagering. It’s already big across the pond, where the London office of Metric Gaming, the company de Knijff founded in 2012, generates “SuperLive” golf lines in high-wattage tournaments for several major sports books throughout the year, at a rate of some 5,000 separate lines per event.

It’s all done on the up and up: Sports betting is legal in much of Europe, as it likely will be soon across much of the United States, now that a federal prohibition on it has been lifted. With the Supreme Court’s recent decision to scrap the 1992 Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act, states now have the right to allow sports gambling. In the wake of the ruling, New Jersey, Connecticut, West Virginia and Mississippi have already stamped new laws that do just that.

Not everyone favors legalization. Critics point to the corrosive effects that gambling can have on families and communities, as well as its potential to corrupt the integrity of competitions; for both ethical and economic reasons, they argue, it is not something the government should get behind. Yet there’s no doubt which side has the momentum. According to some projections, as many as 32 states are on track to greenlight gambling within the next five years.

MORE: Fantasy Six Pack for the RBC Canadian Open

The shifting legal landscape has sent a number of powerful interests into scramble mode—not just state legislatures but also gambling operators and sports executives as they rush to get ahead of the coming changes. The PGA Tour is no exception. After years of treating “gambling” the way golfers treat “the shanks”—as a word best not uttered aloud—Tour officials have come out in support of legalized sports betting. The dollar amounts in play are hard to ignore. Though golf attracts only a tiny fraction of the tens of billions bet illegally on sports in this country every year (estimates on the exact figure vary wildly), a tiny fraction of that sum is still a lot of scratch.

With wider legalization pending, the Tour wants a cut. There is money to be made. There are fans to be “engaged.” Meantime, there are also questions to be answered. Among them: What, exactly, will gambling on golf look like in the not-so-distant future? And what impact, if any, will it have on the game?

“You don’t know what you don’t know, and that’s certainly true of golf,” de Knijff says, his gaze still locked on the Bubba search-party. “But one thing that’s certain is that golfers are inherently bettors. They just haven’t been properly marketed to. Once golfers start to learn about the betting opportunities that exist, you have a totally different ball game.”

* * * * *

To get a better sense of where things are headed, it helps to have a clearer picture of where things are now.

Unlike in the United Kingdom, where plunking down a few pounds on the British Open is as ingrained in the game as the bump-and-run, golf betting in the U.S. is a rarefied practice. In Las Vegas, ground zero for legalized sports gambling, it accounts for less than 2 percent of the total sports book handle.

Many in the gaming industry find this ironic.

“Golf and gambling go hand in hand,” says Brady Kannon, a Vegas-based golf handicapper, columnist and radio personality who also runs a local tee-time booking service. “Since the game’s inception, its players have been gambling among each other. Books are a dime a dozen on golf gambling and all the different betting games you can play on the course with friends. I remember it was a theme here when I was first getting into the business more than 20 years ago. Casinos were interested in meeting the golfers I was bringing into town because they felt that most golfers were probably gamblers.”

They probably were. That they weren’t betting on golf then, and might still not be today, can likely be attributed to several factors, including unfamiliarity.

From a gambling standpoint, golf has never received anything remotely close to the same coverage as football, with betting lines printed in the local paper and TV pundits laying out their picks. Never mind, Kannon says, that a PGA Tour event lends itself more naturally to wagering than many other sports by offering a greater wealth of potential betting options: from straightforward futures (picking a player to win outright) to single-round and tournament head-to-head matchups, to myriad propositions such as make-or-miss-the-cut and win-place-show. As Kannon sees it, the fact that more prospective gamblers aren’t aware of those options is a longstanding problem that now presents itself as an opportunity. For a sport like football, he says, “legalizing betting takes an already established customer base into a new and legal store. For golf, it is more like opening a store that nobody has ever been to before.”

Evidence suggests that golf fans will be eager to scour the shelves. Consider the recent boom in fantasy play, which, until the Supreme Court’s landmark gambling ruling, was regarded by many as a legal stand-in for sports betting. Early last year, DraftKings reported a 2,300 percent jump in its fantasy golf business, along with 15 million new subscribers to the platform, since its launch in 2014.

Legalized or not, explosive growth in gaming would not be possible without what probably ranks as the biggest change of all to hit the gambling industry: the flowering of the digital age. Just as technology has altered golf itself, so has it influenced golf gambling, playing both a limiting and liberating role. One example that longtime bettors might remember emerged in the early aughts with an offshore gaming outfit called World Sports Exchange. Among the gambling options the company offered from its headquarters in Antigua was what it billed as “interactive” golf betting. Modeled on the stock exchange, the online market allowed gamblers to buy or sell shares of a player as the tournament unfolded, with each share meant to reflect the odds that the player had, at that very instant, of winning the event.

Invariably, Tiger Woods would open a tournament as a blue chip: If you wanted him, you had to buy him high. If he went on to play poorly, blocking tee shots, rinsing balls in the water, you might have to sell him low, wishing you’d loaded up instead on, say, Paul Goydos, or some other strong-performing version of a penny stock.

In those years, there were few, if any, other golf betting platforms like it.

“It was exciting and innovative,” says Bill Edler, a veteran sports handicapper who helped set those interactive lines. “I was convinced it was the future—that everything would be going that way in just a few years.”

Engaging as it was, though, the interactive system was also hindered by the tools it relied on. The Internet was still a fairly sluggish conduit. If the World Sports Exchange website lagged or froze, as it often did, you might not get the trade you wanted when you wanted it, or be able to make it based on the most updated information. Ditto if the TV coverage you were watching slipped behind. Within a few years, World Sports Exchange was still in operation, but golf’s online iteration of the stock exchange was gone.

Yet Edler was right: It was where things were going. Once barely a blip in the sports-betting market, in-play (i.e., live) gambling today accounts for around 80 percent of all wagers made. A driving force behind it is the ever faster, freer flow of information.

“Data,” says Metric Gaming’s de Knijff. “That’s the holy grail.”

For years, it was glaringly absent in golf, making a famously fickle game all the more difficult to forecast. With that in mind, when they founded Metric Gaming in 2012, de Knijff and his colleagues spent three years amassing a vast archive of golf-related information. As part of that effort, the company dispatched paid scouts, many of them professional caddies, to PGA Tour events, where they drafted detailed course maps and tracked every shot by every player. It went beyond that. The goal was to understand that data in context, to gauge how different holes played in different conditions; which pin positions were most difficult; whether certain holes or certain stretches of a golf course, or even certain strains of grasses, favored a certain style of play. And so on.

It was scientific research, backed by an understanding of psychology.

“It’s human nature,” de Knijff says. “The more information people have, the more opinions they generate. When people have opinions, they want them validated. What better way to feel that validation than with something to line your pocket.”

De Knijff is not alone in his regard for the nitty-gritty. The PGA Tour has come to see the value of detailed data, too. In announcing their support for legalized sports gambling, Tour officials have made clear their intent to sell stats from ShotLink, the Tour’s vast and ever-growing data archive. Bookmakers and bettors will no doubt be among the buyers.

That’s not the only source of profit the Tour sees. As gambling regulations get sorted state by state, the organization plans to ask for an integrity fee — a share of the betting handle in exchange for its help in ensuring the purity of its competitions. Even before the Supreme Court decision, the Tour was taking public steps in that direction. Ahead of the 2018 season, it announced that it was launching an integrity program aimed at guarding against “betting-related corruption.” That included an education plan designed to help players, caddies and tournament officials sniff out and stave off shady influences or behavior — a suspicious character, say, lurking by the range or the putting green, poking around for inside information.

When big money is at stake, the prospect of scandal shadows every competition, but some more than others. For that reason, the Tour would rather not see betting offered on its developmental circuits; to put it bluntly, the temptation to accept a payoff is likely greater for someone living out of the trunk of their car.

Also important to the Tour is retaining the right to opt out of certain kinds of bets altogether — specifically, those with negative outcomes, such as whether a player will miss a green or dunk one in the water. A single shot might not determine who wins a tournament, but it could very well decide who wins a wager.

It’s not impossible to imagine a player throwing a shot, to say nothing of a spectator trying to meddle with an outcome; there are reasons for yelling “Baba-booey!” other than wanting to sound like an idiot. Tour officials aren’t oblivious to such risks, but they sound confident that they can guard against them. Yes, says Andy Levin-son, the Tour’s vice president of tournament administration, the intimacy of a Tour event creates the possibility of fans influencing the competition, but “we are and will remain vigilant to protect players from distractions.”

Besides, he adds, the chances of it actually happening are pretty slim.

“Betting on golf in the United States, either through Nevada or through illegal channels, has been around for years,” Levinson says. “Further, legal sports betting has existed throughout much of the world for quite some time, and we have not noticed an increased incidence of unruly fan behavior in those markets. If you look at a sport like tennis, which has had in-play betting available for quite some time internationally, there has not been a noticeable uptick of betting-related fan distractions.”

* * * * *

Back at the offices of Metric Gaming, the Players broadcast shows Bubba motioning for a group of fans to make room around his ball, which has settled under palm leaves. Bubba being Bubba, he manages to slash it back onto the fairway. A graphic flashes on the TV: 64 yards left to the pin.

As Bubba grinds, Martin de Knijff recalculates his odds of making par. On average, he notes, Bubba knocks shots from this distance to within 11 feet of the cup, with a 25 percent chance of sticking it to within five feet. That in mind, de Knijff moves him to even-money, a fifty-fifty chance.

“It’s not the easiest shot,” he says. “But he is so good from this distance.” De Knijff smiles, delighted by a betting platform that, he points out, supplies the rush of gambling at a pace fit for the instant-gratification age.

“It’s not just what you might call the ‘degenerate angle,’ the idea that people just want more action,” he says. “It’s the idea that, hey, I’ve got some time to kill, and here’s something I can engage with right away.”

Delivering “SuperLive” to the American market will still take work, not the least of it involving navigating state gambling regulations. It will also hinge on factors beyond de Knijff’s control, such as the willingness of traditional bookmakers to embrace new technologies. But the future he envisions has a large figure in it, with a dollar sign in front. Some estimates put the total gambling turnover in the U.S. as high as $500 billion per year. De Knijff believes golf has the potential to draw 10 percent of that action. Many parties stand to profit: gambling operators, state governments, the PGA Tour, to name just a few. There should be plenty of money to go around.

From the fairway, Bubba sticks a wedge shot to four feet. He’s now a heavy favorite. Moments later, he pours in his par.

“That was fun, right?” de Knijff says as Bubba saunters toward the second tee. “Imagine you had money on that. You got your ‘sweat,’ and you got it right away. And now, if you want, you get to do it all again.”