Golf instruction is ever-evolving, but the best advice stands the test of time. In GOLF.com’s new series, Timeless Tips, we’re highlighting some of the greatest advice teachers and players have dispensed in the pages of GOLF Magazine. Today we revisit an article from our June 1974 issue about what you can learn from your divot. For unlimited access to the full GOLF Magazine digital archive, join InsideGOLF today; you’ll enjoy $140 of value for only $39.99/year.

When you hit a crisp shot with an iron or a wedge, you’ll likely move a little bit of turf. This chunk of grass that goes flying — your divot — is one of the hallmarks of a well-struck shot. Divots aren’t just satisfying aesthetically, though. These chunks of turf can tell you plenty about your swing.

Back in the the 1970s, GOLF Magazine ran a feature about divots and how you can interpret them. You can check it out below.

What you can learn from your divot

Stop! Before you replace that divot, take a moment to check your divot mark. It may seem just a scar in the dirt, but believe it or not, you can learn from it. In fact, if you’re off your game, this is one of the first places you should check. Knowing the difference between a good divot mark and a bad one can immediately indicate appropriate corrections.

To establish a frame of reference, let’s first pin down what a good divot mark should look like. When you hit an iron flush, the divot mark will start right underneath where the ball lay and point directly at your target. It descends fairly steeply into the ground for a couple of inches or so past the ball, then becomes gradually more shallow toward the front end.

Now let’s get to the various bad divots and what they tell you about the shot.

No divot

If you’re taking no divot at all or very little, the first thing to check is whether you are playing the ball a little too far forward in your stance. This will result in a shot flying higher than usual and with slightly less than normal distance. Of course, you can play this shot deliberately — to an elevated green, for example, or over a tree in your path to the target, but you should not do it for a normal shot.

Another possibility is that you are raising the upper body slightly in the backswing. This raises the arc of the swing so that you take little or no divot. An extreme case could result in a topped ball. If you suspect this problem, concentrate on turning your shoulders around a steady head, coiling instead of raising the shoulders.

Fat divot

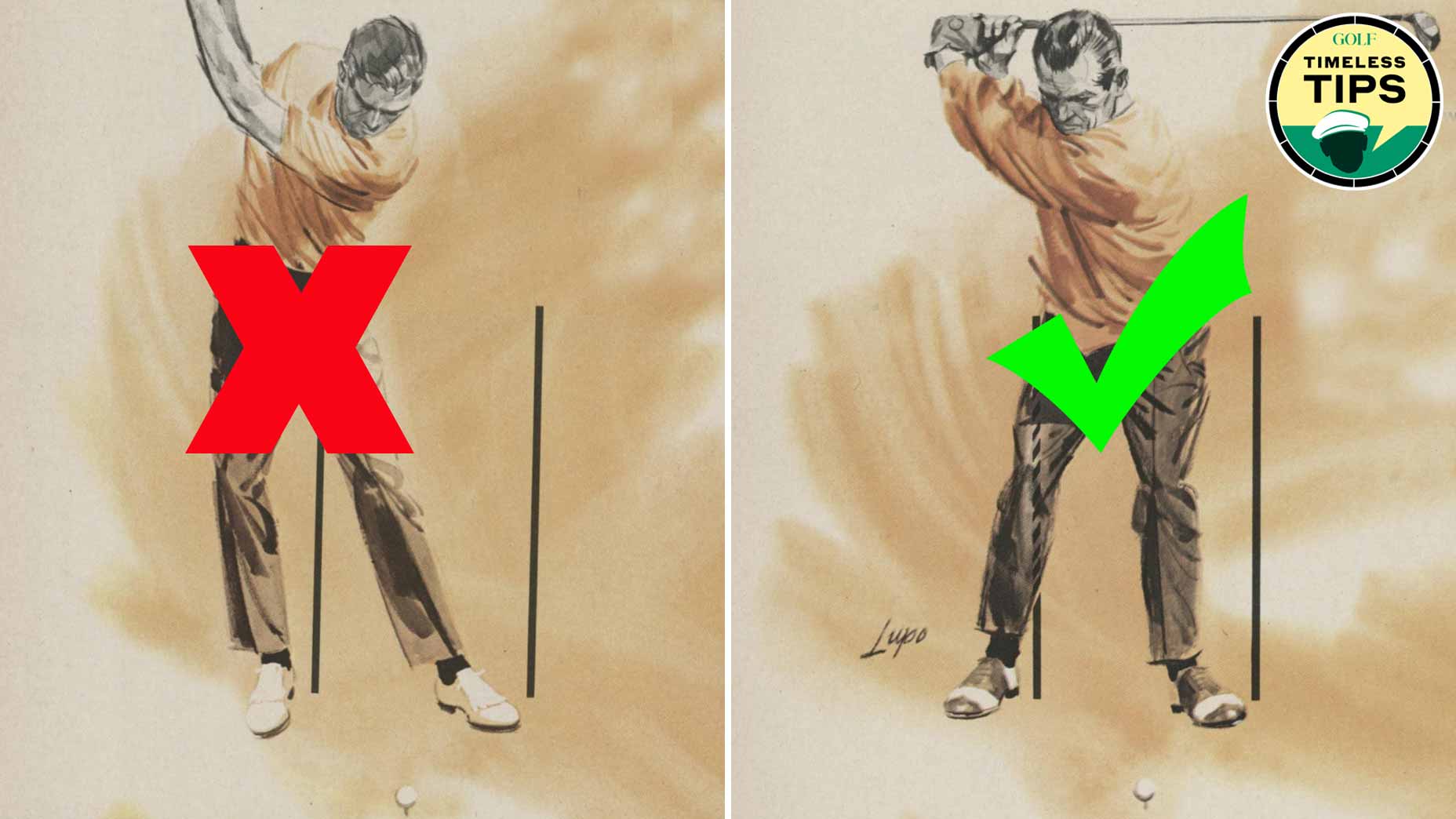

If your divot starts behind the ball, it could be that you are swaying to the right on the back- swing. When you do that, you often don’t sway to the left enough to catch the ball clean. Instead, the lowest point of the arc is behind the ball and you catch it ‘‘fat.”’ To correct this, kick your right knee in a little at address and, as you take the club back, keep your right knee braced inwards.

Another cause of the “fat” divot is the reverse weight shift. Instead of coiling properly on the backswing, the golfer dips the left shoulder while over-bending the left knee. This puts too much weight on the left foot at the top of the swing, and results in a weight shift to the right foot as the player returns to the ball. Again, this puts the lowest point of the arc behind the ball, and yields a fat shot. The key here is even weight distribution at the address. If your weight is even here, you will find it natural to shift your weight to the inside of the right foot on the backswing as you should.

Push divot

Although this divot does point straight at the hole, it is incorrect in that it starts far in front of the point where the ball lay.

The most common cause of the push divot is “frozen” wrists. On the downswing, the golfer slides forward and there is far less release of the wrists than with a normal shot. The resulting trajectory is lower than normal and thus this is a good shot to have in your bag against the wind. But on a normal iron shot, your wrists should be free enough to cock and release fully. You can test for freedom as you waggle at address.

Hook divot

This divot points to the right of target and shows that the arc of the swing was from inside to outside the line to the target. If the clubface was square to the target line at impact, you would hook the ball; if it was square to the line of swing, you would push the ball straight to the right.

The first thing to check in this case is your alignment, since a hook swing can be caused by a closed stance (right foot withdrawn from a line parallel to the line from the ball to the target). At address, check first that a line across your toes is parallel or “square” to this target line. Also check that your hips and shoulders are square to the target line. The line across the shoulders is especially important, as it is the shoulders that create the arc of the swing as much as, if not more than, the feet.

If your feet and shoulders are square to the target line, then you are probably swinging on too flat a plane, i.e., too much like a baseball batter. The way to correct this is to emphasize turning your left shoulder down and under your chin on the backswing. This will give you a more upright swing arc.

Another cause of a flat swing is standing too erect. Make sure that your back is inclined forward about 20 degrees from the vertical for a driver and more on the shorter clubs.

Faulty ball position can also cause a hook divot. Playing the ball way back in your stance toward the right foot can lead to contacting the ball when the club is still traveling from inside to out, i.e., facing right of target. Most of the time this leads to a pushed shot.

Slice divot

This type of divot points to the left of target, and shows that the swing arc was from outside to inside the line to the target. If your clubface is open in relation to the line of swing, you will slice the ball; if square, you will pull the ball to the left.

Like the hook divot, a slice divot can be caused by faulty alignment. So, first check that you aren’t standing too open (left foot withdrawn from a line parallel to the target line). Also check that your shoulders are square. It’s quite common to find that shoulders are misaligned even though your feet are square.

If your feet and shoulders are square to the target line at address, then a “‘slice divot’’ is a clear indication that it is the swing itself that is from the outside to in. An “early warming system” that can alert you to this fault is that your shoulders will arrive at their finish position too early. The left hand and arm will tend to quit and collapse on you as you go through the ball.

Basically, the most common reason for a slice divot is an over-active right side. So, concentrate at address on setting up with a strong left side: Keep the left arm and hand fairly firm with the arm and shaft in more or less of a straight line, lighten the right hand’s grip and leave the right arm ‘‘soft’’ and more in toward your body than the left. Emphasize a full shoulder turn going back. This will put you on the inside track to start with and lead to the desired downswing path from the inside.

As with the hook divot, don’t forget your ball position. Playing the ball way forward in your stance off your left foot can lead to contacting the ball too late in the swing, when the clubhead is already going inside. The result is a slice divot and probably a ball pulled left of target.

As the above indicates, there is much that you can learn from your divot. If your divot is right, then the odds are your swing is right, too. However, if your divot is one of the “bad” ones discussed here, a trip to your professional would be in order.

In the meantime, there are some practice techniques that you can use to help yourself get back on the right track.

If you suspect that you’re taking either a “fat” or “punch” divot, check this by pushing a tee into the ground at the address outside and opposite the center of the ball. After you have hit the shot, you can readily see where the divot starts.

Another way of checking on this is to scratch a line on the ground at right angles to the target line. Sole your club just in back of the line and take your normal swing. Not only can you see whether the divot starts at the right spot, but also whether it is dead on line to the target or pointing to the right or left.

If you still have trouble taking a correct divot, push a tee into the ground just in front of the ball. This not only encourages you to swing through the ball, but is a great aid to straightening out the divot and the resulting shot. One of the beauties of working to get the correct divot is that it concentrates attention on the business end of the swing — the impact area — rather than getting confused by too many details in the swing itself.

As one great teacher put it: There’s only one categorical imperative in golf — hit the ball!

In the interests of keeping things as simple as possible, we earlier defined a good divot as one that points directly at the target. However, next time you go to a professional tournament, go to the practice ground and study the divots that a top-class player takes. You will discover that, in most cases, their divots point slightly to the left of the target, yet the ball flies essentially straight toward the target. It seems, therefore, that they have used a slightly outside-to-in swing, yet the shot flies straight. How come? Why doesn’t the professional slice with this action?

The answer is that, during the downswing, the shoulders rotate around the spine, the axis of the swing. Thus, the downswing path for a straight shot approaches the ball from the inside, is square to the ball at impact and then goes inside again to the finish. This inside-square-inside path of the clubhead means that the divot on a straight shot will usually point very slightly to the left of target, since the club is moving inside after impact while the divot is being taken.

Returning to the practice tee at the pro tournament again, you will notice that some of the players do take divots that point straight at the hole. There are two reasons for this. First, the player could be aligned slightly right of target. Second, they could have exceptional extension through the ball, which would keep the clubhead on line longer after impact.

What this means is you must “read” your divot in conjunction with the flight of the ball. If your shot is straight, just replace the divot and go hit the next shot!