Bryson DeChambeau shot an even-par 70 during the third round of the 2020 U.S. Open, which was quite impressive considering his bogey-bogey start. The second bogey was the product of a drive that sailed alarmingly left off the tee — the kind of shot that, for many golfers, would’ve been the start of the end.

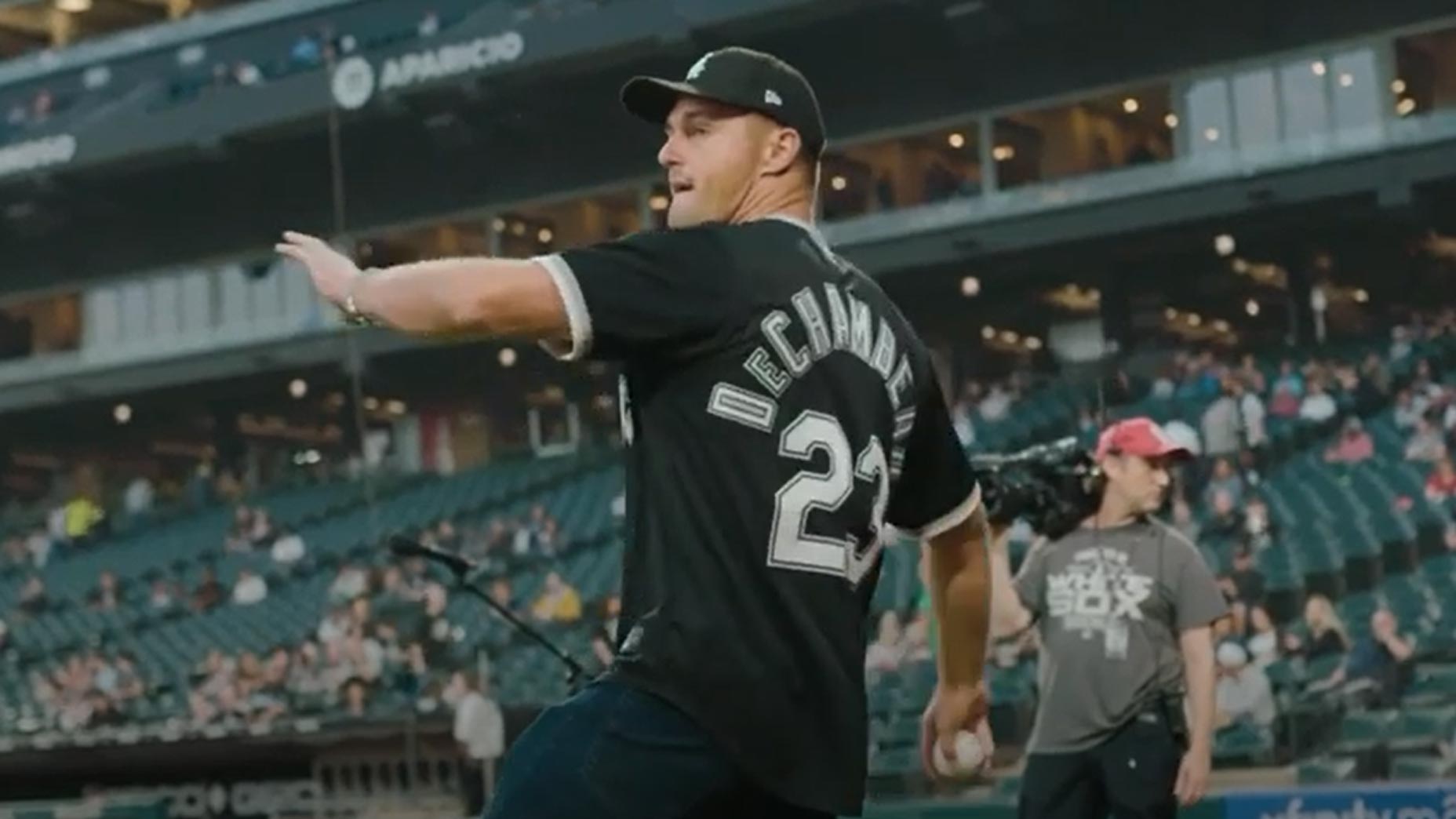

Sub-optimal pic.twitter.com/TQCJ27u7e0

— LKD (@LukeKerrDineen) September 19, 2020

That “overdraw,” as he referred to it later in his round, plagued him all day — he hit just 21 percent of his fairways. After his round he explained the cause of his miss:

“I felt like I was super comfortable, and then one of my governors just kind of broke down and I couldn’t get it back all day,” he said.

Naturally, that Bryson-ism prompted a flurry of questions on social media. What is the “governor” that Bryson is talking about? Its full name is an “anatomical governor,” and above all else, it’s the most important element of Bryson’s golf swing.

Understanding end ranges of motion

Bryson tries to swing fast — we all know that by know — but he’s trying to swing fast within what he calls an “end range of motion protocol.”

Put simply, an end range of motion is the amount a joint in your body can move until it can’t move anymore. Hold your right arm out in front of you, and turn your wrist as far to the right as much as it can. When you feel it stop, that’s your joint reaching its end range of motion. Bryson is obsessed with the end ranges of motion of his joints, and using them to help boost his consistency. He incorporates them everywhere from his putting to his full swing.

Why? Because, as his theory goes, when you put your joints into their end range of motion, it means they can’t move anymore. Them not moving is your body’s “anatomical governor” — a natural physical governor that limits the number of ways it can move.

The most important anatomical governor in Bryson’s swing, according to Bryson, is his left arm. He wants to keep it straight and locked in for as long as possible during his golf swing. When he does that, it prevents the clubface from closing unwantingly.

Jordan Spieth, believe it or not, was his inspiration for the move.

“I started realizing quickly that I couldn’t ever hit it left by going to the max end range of upper and internal rotation,” DeChambeau said. “I may hit it 30, 40 yards right, but I never missed it left.”

Bryson used to hit a fade, but his quest for more distance coincided with him switching his stock shot to a draw — which he told me at the BMW Championship is only possible because of the way his left arm works in the golf swing.

Which brings us back to Saturday at the U.S. Open. When he talks about his “governor” breaking down, that’s what he means: His left arm, which wasn’t staying locked in place and therefore allowing the clubface to close, hence him missing a handful of shots to the left. Rest assured, he put in some hard work after his round (he might still be there, to be honest) to make sure his golf swing was back in a place where he wants it, ready for U.S. Open Sunday.