How much do golf balls weigh? Here’s everything you need to know

How much do golf balls weigh? Here’s everything you need to know

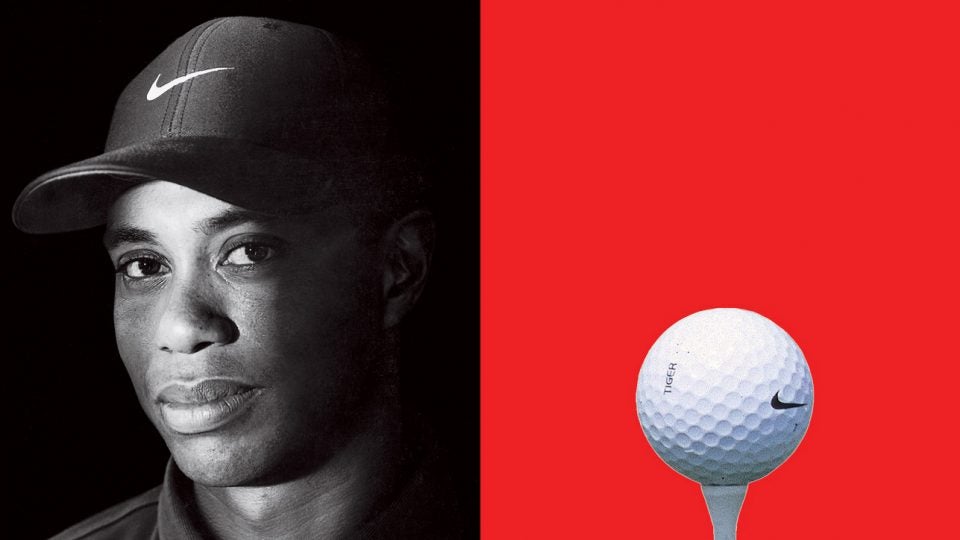

Tiger Woods and the golf ball that (almost) changed it all

In 2000, Tiger Woods put a new Nike golf ball into play and then won the U.S. Open by a record 15 strokes. Here’s the full story behind the ball.

Kel Devlin was just sitting down to dinner at home in Portland, Ore., when the phone rang that Sunday. It was Tiger Woods. “If I had my ball this week, I’d have won by five,” Devlin recalls Woods saying. Thirty-one calendar days later, Woods did have his ball, and he used it to destroy the record book and obliterate the status quo.

Prior to that conversation in May 2000, Devlin hadn’t heard Woods refer to the prototype ball as such. In his role as Nike Golf’s global director of sports marketing at the time, Devlin had spent nine months collaborating with Woods on the development of the Nike Tour Accuracy. The ball was unlike any Woods had played previously, including the Titleist Professional he used to shoot a final-round 63 that very day. Despite the gaudy number, Woods had finished one stroke behind winner Jesper Parnevik at the Byron Nelson Classic. The U.S. Open at Pebble Beach was a month away, but “my ball” was still an unproven prototype.

“Can you meet me in Germany on Tuesday morning?” Woods said into the phone.

The Titleist Professional that Woods played at the 2000 Byron Nelson was the go-to ball on the PGA Tour in those days. Its liquid-filled core and wound construction closely resembled the venerable brand’s Tour Balata, but an Elastomer cover reduced the excessive wear and tear that the balata-covered version suffered at the hands of the world’s fastest impact speeds. Players routinely used a balata ball for only three holes before discarding it because of all the scuff marks, rotating three new balls per nine holes. The Titleist Professional was the best of both worlds.

The prototype of the Nike Tour Accuracy, like the player pushing its development, was a tiger of a different stripe—a three-piece ball of solid construction, with a molded rubber core injected with synthetic material, and a multilayer, urethane cover. In the prototype phase, the goal was to create a ball that offered the feel and performance Tour players were accustomed to, but with substantially less spin and more speed than a wound ball.

During testing, Woods blew through numerous versions of the Tour Accuracy, carefully detailing its shortcomings for Devlin and Hideyuki “Rock” Ishii, a Bridgestone Golf engineer who was actually bringing the ball to life. (Woods confirmed earlier this year that Bridgestone made his Nike ball for nearly 18 years.)

Devlin and Ishii spent countless days and hours crisscrossing the country with prototypes in suitcases—sometimes interrupting vacations to do so—to go to wherever Woods had time to put the latest versions of the ball through their paces.

“He was fantastic to test with,” Devlin says. “He got so good at it that he started playing a game. We’d be testing drivers and he’d say, ‘I hit that one a little low on the face, so that’s probably 2,600 RPM.’ We’d look at the launch monitor and it would be 2,570.”

Not surprisingly, Woods had an other-worldly feel for the feedback the ball was giving him. At one point, he thought he detected a discrepancy between the “click” produced when the prototype contacted his putter and the audible signal from the Titleist ball under the same circumstances. A frequency analysis was performed with a fast-Fourier transform sound analyzer, and it verified Woods’s suspicion. At around 4,000 hertz, there was an audio peak that could not be replicated by the Tour Accuracy prototype at that stage, prompting a minor tweak to the ball’s cover to suit Woods’s finely tuned ear.

During a session at Big Canyon Country Club in Newport Beach, Calif., in early 2000, Woods narrowed the prototype field down to two versions. He loved the strong flight of the ball, its additional 10 mph of ball speed and the way it ripped through the wind, but he didn’t want to feel as if he were rushing the process. He told Devlin testing would halt until October.

“He liked the ball, but we were just waiting at that point,” Devlin says. “There was no indication he was going to use it during the 2000 season.”

Devlin, the son of Tour player Bruce Devlin, who regularly contended in majors in the 1960s when the Big Three were at the height of their powers, was caught flatfooted by Woods’s request to resume testing at the Deutsche Bank-SAP Open in Hamburg that spring. The final version of the ball that Woods wanted to put into play was at Bridgestone’s facility in Japan, where it was already Monday morning.

Devlin quickly rang Ishii in Japan to see if he could jump on a flight that afternoon with the balls in tow. Ishii thought Devlin was pulling his chain.

“I’m dead serious,” Devlin said. “We’re going to meet Tiger Tuesday morning on the first tee.”

Devlin packed his bag and headed to the Portland airport. At the appointed hour on Tuesday morning, he and Ishii headed to the first tee, where they received a warm welcome to Germany from Steve Williams, Woods’s long-time caddie.

“What the f— are you two idiots doing here?” Devlin recalls Williams saying.

When Devlin told Williams their purpose, he received a one-word response: “Bulls–t.”

Rain and wind were whipping at their faces a few moments later when Woods arrived and immediately pumped a drive with a Titleist Professional. Devlin watched as the left-to-right wind caught the ball and pushed it into the rough. Woods teed up the Nike Tour Accuracy and ripped it on the same starting line. It moved only slightly— maybe five yards—and landed in the center of the fairway. It was a seminal moment for Devlin that verified the ball’s competency in a game situation.

Back in the States for the Memorial Tournament, Woods confirmed during an early-week press conference that the ball was still in the testing stage, but that he was comfortable enough with the performance to put it in play. “The only way to [make sure it feels good] is to test it in competition,” he said.

By the end of the week, Woods had left the field at Muirfield Village five shots in his rearview mirror, the 19th win in his young PGA Tour career. After just two starts with the Nike Tour Accuracy, Woods was sold—with one reservation. According to an insider who had direct dealings with the ball, the hesitancy had to do with Woods’s distance judgment and trajectory control in windy conditions.

ADVERTISEMENT

“He was consistently longer across the board with the ball,” says the source, who requested anonymity. “Seven yards with the long and middle irons, three yards with the wedges. The ball was much stronger into the wind, but Tiger was used to seeing consistent flight and distance.”

Two weeks later, at the U.S. Open at Pebble, Woods cast aside his concerns and pushed the pedal to the floor in an opening-round 65. The next day serious gusts kicked up off the Pacific, and while the field reeled, Woods flighted darts all day. He led by six after 36 holes, and when he finished the week he was 15 strokes clear of the field. He had set or tied nine U.S. Open records, and won the first of four consecutive majors. And he did it all with a new ball that seemed impervious to the wind and rain.

The only issue Woods ran into with the ball that week was one he was unaware of at the time. After Tiger rinsed his tee shot on the iconic 18th hole on Saturday morning of the fog-delayed second round, Williams handed him what turned out to be the last Tour Accuracy left in the bag. Woods had been practice putting in his hotel room the night prior and forgot to replace the balls, leaving him with just two when he returned to the course. It wasn’t until after the round was completed that he realized what was going on. It was the closest Woods came all week to derailing the most dominant performance in golf history.

At the 2000 Masters, one month before Woods officially put the Nike Tour Accuracy into tournament play in Germany, 59 of the 95 players had used a wound ball. In the ensuing year, Woods won nine events. When he capped off the Tiger Slam in 2001 at Augusta National, all but four players in the field used a solid-core ball.

The effect that the development of the Nike Tour Accuracy and Woods’s use of it had on other players and golf history wasn’t lost on Woods. Years later, in 2014, he said, “The biggest transition I ever made was in 2000. I won four straight majors with that ball, and the rest is history, because wound-ball technology is gone. Everyone switched. Being a part of that wave of innovation was exciting for me.”

Being first out of the gate doesn’t always guarantee success, especially in the equipment industry. If that was the case, Top-Flite’s Strata Tour would’ve lapped the field, with Mark O’Meara leading the way. O’Meara embraced Top-Flite’s solid-core ball three years prior to Woods making the jump, and won seven times worldwide, including the Masters and British Open during the 1998 season, at the age of 41.

O’Meara didn’t have anywhere near the cachet and marketability Woods possessed, which tempered the near-instant success that Strata enjoyed before the Tour Accuracy even made its way to the market. But the moment Woods switched to a completely different ball construction, the entire world took notice.

The ball that almost changed the game wasn’t quite the commercial success it potentially could have been. According to Devlin, the goal was to use the momentum from Woods’s historic U.S. Open win as leverage to wrest away significant market share from Titleist. However, Nike didn’t have a way to manufacture their own golf balls in-house, which meant there was no existing supply to meet demand. “We couldn’t get production ramped up and the ball to market until October, maybe November of 2000,” Devlin said.

Even if the ball had been in full production, Titleist was an imposing competitor and a highly innovative company in its own right. While Nike was prepping its sales reps for a fall run, Titleist had been quietly developing the Pro V1 for five years. It had a solid core surrounded by Surlyn casing, a 392-dimple icosahedral design and a homegrown urethane cover that doubled as a veneer. The damned thing practically sparkled.

The second week of October, Titleist reps showed up at the Tour event in Las Vegas packing 400 dozen prototype Pro V1s. Forty-seven Tour players immediately put Pro V1 in play, making it the largest pluralistic shift of equipment at one event in golf history. Billy Andrade played the ball and won the tournament. Due to the incredible momentum Pro V1 experienced in its first few months on Tour , Titleist accelerated the market launch of Pro V1 forward from March 2001 to December 2000. The damage to the Nike Tour Accuracy’s future was done, because in the old ball game, what PGA Tour players play is what sells to the masses.

Devlin remembers thinking, “F—, we missed the window.”

Nike Tour Accuracy had its moments, of course. A few months after Woods notched his fourth consecutive major, David Duval won the Open Championship playing the ball and Nike clubs. More than a few everyday golfers regularly wanted to play the ball that Tiger played, which is partly how Nike was able to get to a double-digit number in golf ball market share at one point. But it still wasn’t enough to pass Titleist or keep Nike’s hard-goods operation afloat. To this day, Devlin still ponders the circumstances around the ball he still believes could have been king.

“If we’d had enough capacity, and I could have gotten the sports marketing folks and Phil [Knight] to buy into the bigger program…if we’d had the ball available to any Tour player who wanted to use it four weeks earlier than we did…”

Nike’s 20-year run in golf hard-goods came to an end in 2016 when it exited the equipment business. But the moment Devlin, Ishii and Woods stood on that tee in Germany nearly two decades ago, a new force was unleashed on the game, and it reverberates yet.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT