Tiger Woods’ mother had a singular focus: raising a world-beating son

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

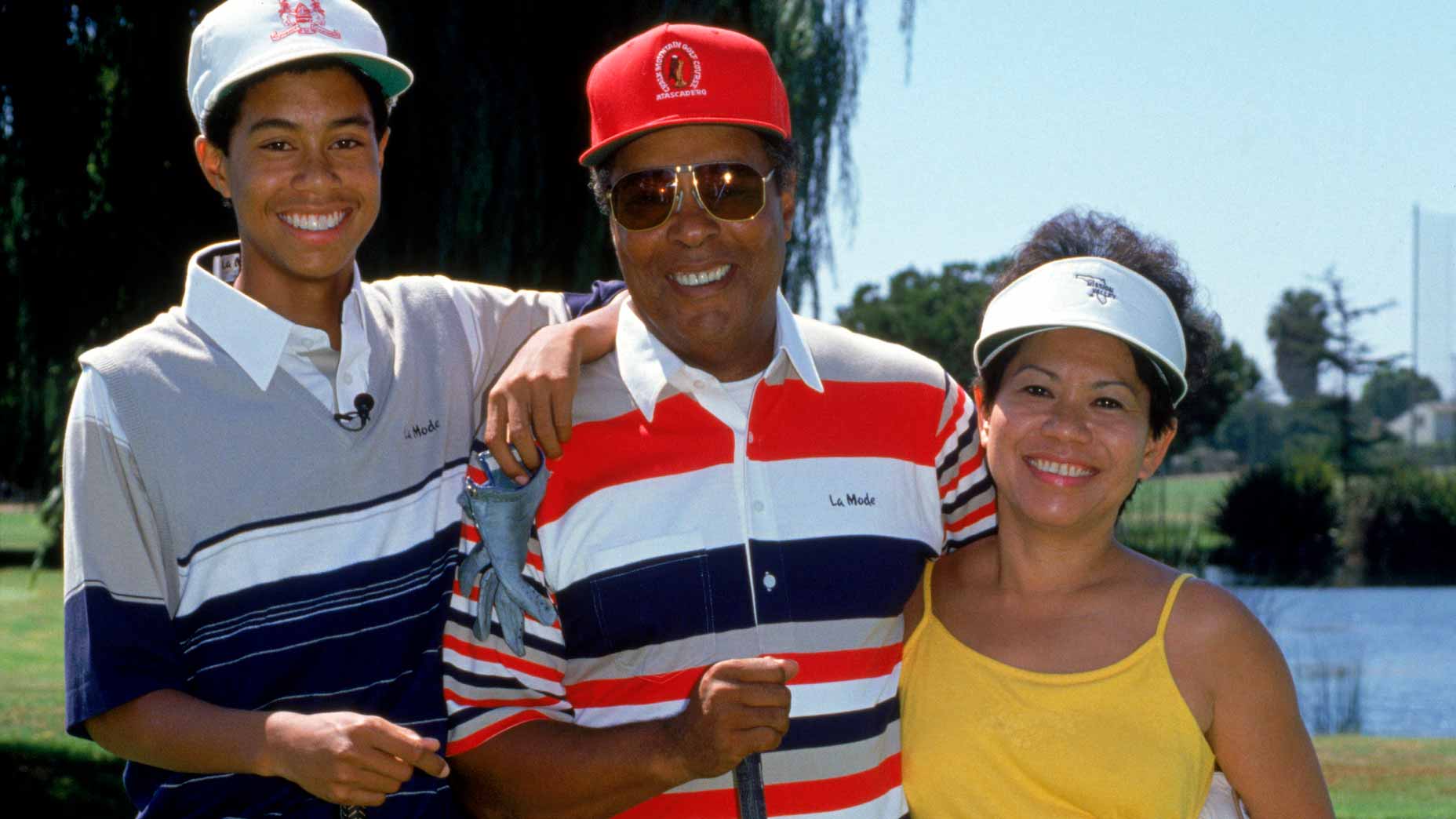

Tida and Tiger Woods pictured in 1997.

getty images

Most of us cannot readily name Big Jack’s mother. Helen Nicklaus died on the eve of the 2000 PGA Championship at Valhalla, a course her son designed. Fewer yet can name Young Tom’s mother, Agnes Morris, who died in 1876, the year her husband, Old Tom, had a ho-hum T4 finish at the Open Championship on the Old Course, where he was the greenkeeper. But everyone in golf knows Tiger’s mother, Tida. The most famous mother in golf.

She was Kultida Punsawad Woods on her legal documents but wherever she went in this world, over the course of her remarkable, globe-crossing 78 years, she was Tida. Tida Woods died Tuesday; Tiger did not disclose a cause. In a statement, Tiger referred to her as my dear mother and Mom. But when he received the Bob Jones Award, the USGA’s highest honor, at the U.S. Open in Pinehurst last year, Woods called her Mommy. She was right there in the first row, alongside her only two grandchildren, Sam, and her kid brother, Charlie.

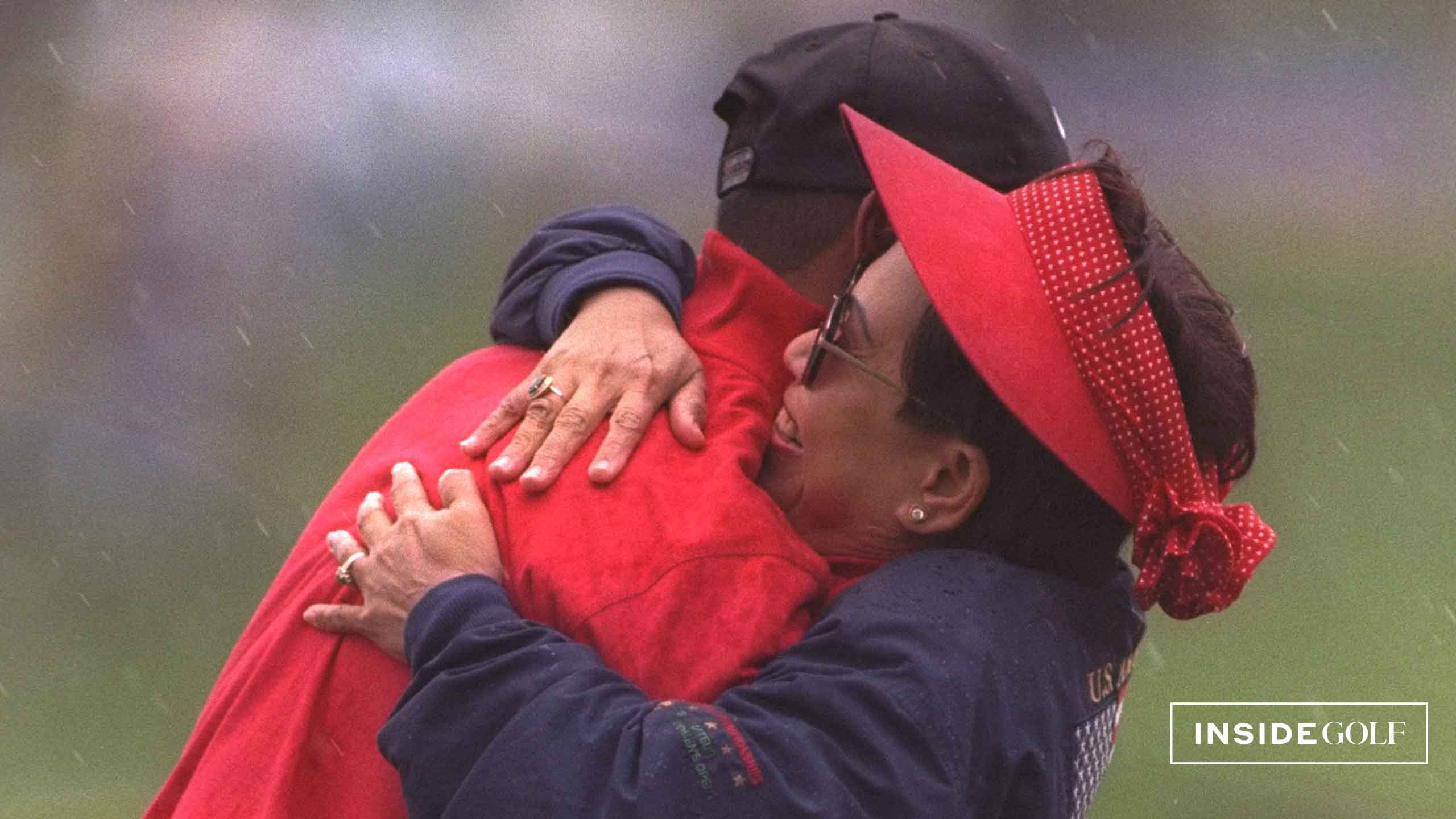

Tida was always in the first row. She was short, feisty, direct, strong in every way, and if you were in her way, watch out. She was in the first row when Woods made that painful public apology in a ballroom in the clubhouse at the TPC Sawgrass in 2010. She was in the first row, right behind the 18th green, when Tiger won his first Masters in 1997. She was in the first row when Tiger was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 2022. She had one husband (Earl), one child (Eldrick) and seemingly one purpose, to raise a take-no-prisoners son.

Tiger grew up in a tidy suburban house in Cypress, Calif., choking with cigarette smoke (his father) and the smells of Thai cooking (his mother). Inside, the house was not like the others in their development. Tiger has said it a thousand times: his father, the former lieutenant colonel, was a softie. His mother packed heat. In the 1970s and 1980s, she drove Tiger in her Plymouth Duster to junior golf tournaments all over Southern California, and she wasn’t there to make friends. She was there to watch her son hoist trophies, and he did.

Tiger’s father had the mentality of a Black man who knew firsthand the pain of Jim Crow and a segregated America. Tiger’s mother, who came to the United States from Thailand, had an immigrant’s bring-home-straight-As mentality. Over the past 25 years or so, as Tiger’s outsized success has become a simple fact of sporting life, that part of the equation has been forgotten. But the blending of cultures is Tiger’s true origin story.

Earl and Tida never divorced but they led separate lives for years. If there was any one thing that kept them together it was Tiger’s golf skill and his promise. In word and deed, his devotion to both of them is obvious. It was a stunning sight to see Tida in the Augusta National clubhouse on Masters Sunday in 2019 as her son played the back nine, trying to win his fifth green coat. She sat with friends and her grandchildren and stared at an elevated TV. As the room murmured and cheered various shots, she was a study in impassivity.

For Tiger Woods and late mom, Tida, two memories tell a storyBy: Dylan Dethier

With the outcome semi-clear she walked from the clubhouse, got her five-foot self over a security chain without assistance and stood on a hillock beside the 18th green. In Butler Cabin, in an interview with Jim Nantz, Tiger remembered the trips in the Duster.

Tiger has talked in general terms about what he learned from his mother, a practicing Buddhist, but he has kept private any details of how it shaped him. Tiger has always given the appearance of being a child of the North American experience, playing Little League baseball, rooting for the Raiders, going to Vegas. Someday we may find out that his Eastern side — his Buddhist side, his Tida side — opened a window to the game’s mysteries in ways that defy post-round interviews. Be the ball times infinity.

Something has to explain winning a Masters by 12 and a U.S. Open by 15 — beyond skill. Skill alone gets you a two-shot win.

Let’s not play Kumbaya yet. When Tiger beat Davis Love in an early-career event, Tida said, “Tiger steal his heart.” At Presidents Cups and Ryder Cups, Tida didn’t pal around with Penta Love and Mary Mickelson. Her whole life seemed to be her devotion to Woods, and later to Tiger’s children.

When Helen Nicklaus died, just before the start of the 2000 PGA Championship, Nicklaus decided to play in the tournament, saying that’s what his mother would have wanted to do. For the first two rounds, he played with Woods, who went on to win that week, on Nicklaus’s course. The summer of 2000. Tiger was on fire. Now when Tiger (perhaps?) plays later this month, at the Genesis Invitational, he will again be following in Nicklaus’s footsteps, trying to play tournament golf in the face of grief.

Unlike Helen Nicklaus and almost every other golfer’s mother, Tiger’s mother was often in view of TV cameras. Not that she welcomed it. She didn’t talk to reporters very much, and when she was quoted, she wasn’t often happy about it. She did talk to a reporter after her son’s public apology, when his private life was revealed to the world and his life imploded. She saw it for what it was, an act of media spying on a person who wasn’t an elected official, wasn’t a clergyman, wasn’t a teacher. She was angry. But she also saw something much bigger going on.

“Buddhism teaches you to go deep inside your soul and look through for yourself and correct the bad thing to be a good thing,” she said. We really don’t know much about Tiger’s private life and private thoughts, but we know a lot about his public life, his golfing life. As a golfer, he was always trying to turn weaknesses into strengths, and he did it in ways few others have.

Eighty-two wins, 15 majors, membership in the World Golf Hall of Fame, winner of the Bob Jones Award. No Tida, no any of that.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bambeger@Golf.com.

Latest In News

How Johnson Wagner duffed his way to golf-TV stardom

Michael Bamberger

Golf.com Contributor

Michael Bamberger writes for GOLF Magazine and GOLF.com. Before that, he spent nearly 23 years as senior writer for Sports Illustrated. After college, he worked as a newspaper reporter, first for the (Martha’s) Vineyard Gazette, later for The Philadelphia Inquirer. He has written a variety of books about golf and other subjects, the most recent of which is The Second Life of Tiger Woods. His magazine work has been featured in multiple editions of The Best American Sports Writing. He holds a U.S. patent on The E-Club, a utility golf club. In 2016, he was given the Donald Ross Award by the American Society of Golf Course Architects, the organization’s highest honor.