The year’s best-selling driver offers 2 standout features

The year’s best-selling driver offers 2 standout features

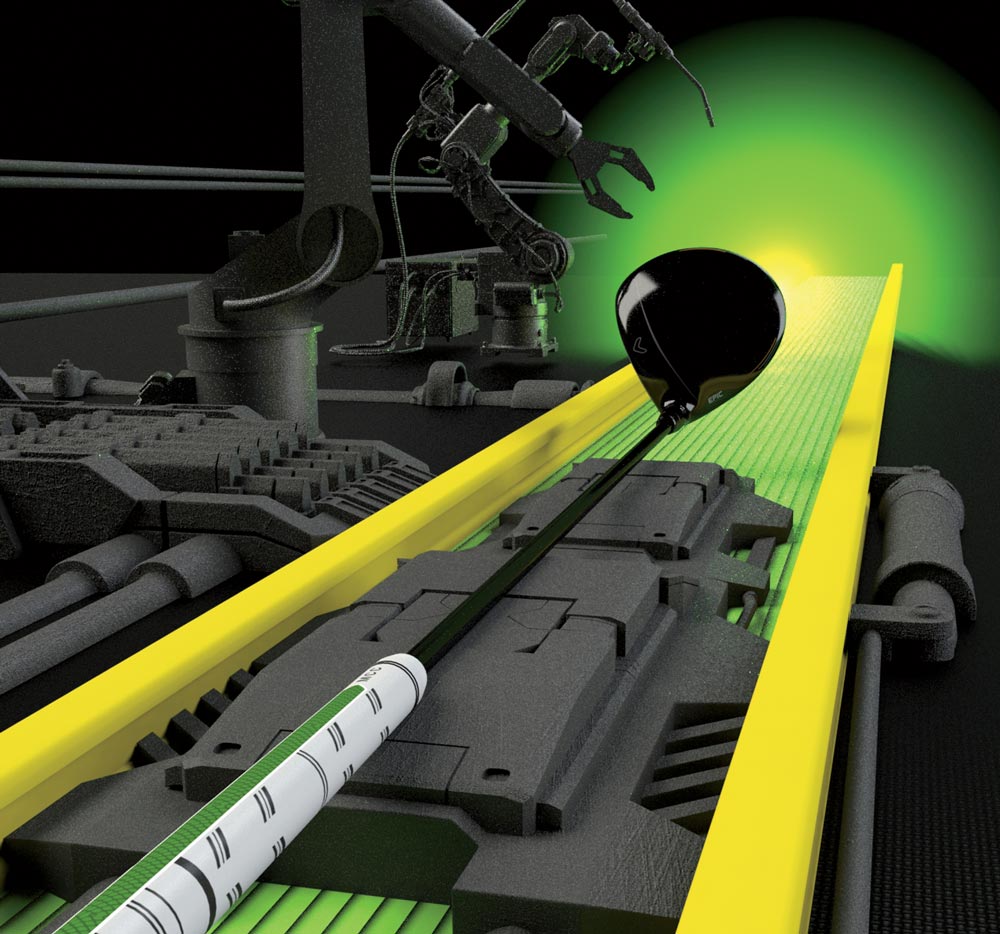

Circuit Act: Callaway’s new hotshot club designer is a supercomputer

The newest hotshot club designer at Callaway headquarters, in Carlsbad, California, doesn’t mingle much with colleagues. No water-cooler chats. No friendly office pools. Laboring in isolation, in an air-conditioned space behind locked doors, this employee is the nerdiest of nerds. Charisma? No. But talk about impressive quantitative skills.

In some work settings, a Poindexter of this kind might be off-putting. But for Callaway staffers, it comes as no surprise — or disappointment — that their dweeby young team member isn’t a people-person. That’s because it’s not a person at all. It’s a supercomputer pulsing with Artificial Intelligence (AI), its mind engaged in tasks that may reshape the future of golf equipment manufacturing. Already, its efforts have shaken up the industry, giving rise to a driver unlike any the world has ever seen.

“When I first saw what it had come up with, it was one of those ‘What on earth?’ moments,” says Alan Hocknell, Callaway’s senior vice president of research and development. “You could give me an entire lifetime, and I’d still never dream of something like it.”

That something is the convention-flouting face on the Epic Flash driver, which was released early this year and which, according to the market research firm Golf Datatech, currently ranks as the number-one-selling driver in the U.S. In the hands of such stars as Phil Mickelson, Xander Schauffele and Francesco Molinari, the Epic Flash has been involved in more PGA Tour and worldwide wins (10, as of early April) than any other new driver model. In the hands of everyday players in Callaway’s own testing, it has accounted for an average distance gain of 12.9 yards.

That added distance is the by-product of increased ball speed, which in turn is propelled by a clubface design so counterintuitive it took a non-human to intuit it. Callaway calls it Flash Face technology, and it features a series of asymmetrical internal ripples, reminiscent of the patterns on a thumbprint. The ripples radiate unevenly across a face that is thinnest at its center, a radical departure from conventional modern driver faces, which are thickest at their center and thin around the edges.

In the Epic Flash, the Flash Face is paired with Callaway’s Jailbreak technology, a twin set of internal, hourglass-shaped bars that connect the crown to the sole, stabilizing both components at impact to further boost ball-speed. That’s the broad-stroke explanation. Exactly how and why the entire package works is best understood through sophisticated physics, albeit not the same sophisticated physics that Hocknell, who has a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering, learned about in grad school. That many of his peers have similarly lofty educations has been a boon to the industry, pushing innovations far and fast. But, Hocknell says, it has also produced a rush to uniformity.

“What we began to notice was that the face design of our drivers, and those of our competitors, were starting to take on a certain sameness,” Hocknell says. “And we thought, ‘Hmmm, we all went to similar engineering schools. Maybe we’re the problem.'”

Nothing like AI to shake things up. Although computer modeling isn’t new to golf — it was in its infancy when Hocknell got his start in the 1990s — every technology has limits. For equipment manufacturers, one of those limits is how efficiently computer modeling works. New clubs aren’t developed overnight. They’re brought to market through a time- and labor-intensive trial-and-error cycle that Hocknell says boils down to this: “You design it. You simulate it. A human decides what to do about it. And then you go around again.”

In the typical development of a product, he adds, “you can probably go through that process five or six times.” Callaway’s new supercomputer shifts that cycle into hyper-drive. Not only can it process reams of data at a rate that would make Bryson DeChambeau’s wonky head spin, it’s also capable of “machine learning,” drawing lessons on its own from mountains of information, without a human programmer to guide it. In dreaming up the Epic Flash, the supercomputer sifted through 15,000 iterations of driver-face design before settling on the optimal configuration. It did all this over the course of a weekend. Saddled with the same job, Callaway’s old computer modeling systems would have toiled away for months.

Such lickety-split wizardry doesn’t come cheap. To assemble its new work-horse, Callaway spent millions leasing hardware and software (it also wrote some of its own code in-house), an outlay reflected in the top-dollar price tag of the Epic Flash, which retails for $529.

ADVERTISEMENT

Little about the look of the supercomputer — a stack of black, rectangular processors that measures a few feet wide and roughly eight feet tall — suggests that there’s anything special about it. But that’s pretty much moot, since Callaway keeps it hidden from prying eyes. It’s a delicate machine, sensitive to temperature, allergic to dust, entirely off-limits as a platform for setting down your morning coffee. Most company employees are forbidden to be near it.

“They don’t even let me in there,” Hocknell says.

Since first punching the clock last year, the supercomputer has barely had a day off. In club design, one’s duties never really end. That it hasn’t tired or complained calls to mind a concern, voiced in other industries, that robots are destined to take all our jobs. Hocknell understands that thinking, but he says that in this instance, he isn’t worried. For all its many gifts, the supercomputer can’t produce a golf club on its own.

“It couldn’t help us build the thing,” Hocknell says. “It couldn’t manufacture a prototype to see how it performed in the real world.” Moreover, the work it did on the Epic Flash was assigned to it by humans. “The computer is there for its speed and its ability to handle a lot of numbers,” he adds. “But the way that it learns is still down to us.”

So, what will it learn next? In the course of its machine-human collaboration, Callaway has produced what it bills as the golf industry’s first AI-generated consumer product. It won’t be the last. The potential exists to take a similar approach to irons, putters, hybrids and on. The direction of the work will depend on many factors, starting with the result that humans are after.

“The fact is, you don’t always have the same goals,” Hocknell says. “With drivers, it’s pretty simple: you want long and straight. But with irons, consistency of distance is more important. So the question becomes, how do you teach a computer to optimize for that?”

Throw in other variables, Hocknell says, such as the discovery of a new material, and the possible avenues of exploration grow wider still.

In the meantime, Callaway faces a more mundane question: what to call its supercomputer. Unlike HAL, the AI villain from 2001: A Space Odyssey, Callaway’s young brainiac doesn’t have a name, and the job of coming up with one falls squarely on the humans. A geeky character like a supercomputer isn’t going to walk up and introduce itself.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT