Beginning Dec. 14, GOLF.com is rolling out a story per day honoring the legendary Arnold Palmer, who died on Sept. 25. These pieces appeared in a special tribute issue of GOLF, which celebrated the life of one of the sport’s greats. Welcome to the 12 Days of Arnie. For more on the King, click here.

In the modern era, when athletes like LeBron James and Roger Federer mint as much off the court as on, it’s easy to forget where it all began. It’s true that early American sports stars like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb enjoyed endorsements, routinely taking cigarettes, automobiles and clothing in exchange for the use of their image or name. But until Arnold Palmer came along, big-time sports marketing — and big-time sports marketing dollars — didn’t exist.

How did a scrappy kid from Latrobe, Pa., make it rain? In 1960, the year of his second and third major wins, Palmer made a handshake deal with Mark McCormack, the founder of IMG, to be his agent. Before that, Palmer’s wife, Winnie, tracked his business affairs, which included a three-year, $5,000 pact with Wilson, a deal so favorable to the equipment manufacturer that it required Palmer to return his clubs if he underperformed on Tour.

In the first few years of the partnership with McCormack, Palmer’s annual endorsement income rose from $6,000 to a half million, a stunning amount of money in the early sixties. What loosened the purse strings? McCormack’s vision of what the Palmer brand could be. Quickly, he took advantage of the newly popular television medium, a perfect fit for his client’s good looks, charisma and, above all else, authentic American persona.

MORE: Buy Sports Illustrated’s Arnold Palmer Commemorative

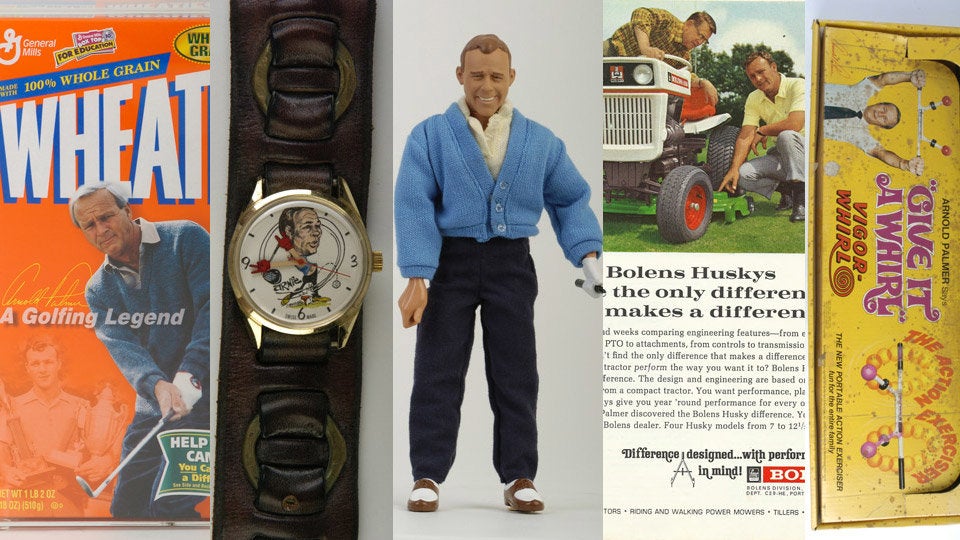

Palmer, of course, wasn’t clueless about his appeal. When he trademarked his name in 1968 and created Arnold Palmer Enterprises, the choice of a company logo was an umbrella, under which all things Arnold Palmer — the endorsement deals and myriad other business interests — would fall. Palmer the pitchman was especially persuasive in a 1981 Pennzoil ad, in which he sat atop his father’s tractor. The ubiquitous TV spot struck the public as the real deal because it was — his dad had used Pennzoil for years, and Palmer was simply speaking his truth to the camera. This template — the inclination to endorse only products and enterprises he personally used or believed in — was key to the King’s decades-long success as a brand ambassador.

In the last 50-plus years, Palmer lent his Everyman authenticity to sponsors as varied as Cadillac, Rolex, Hertz, Callaway, Heinz, Coca-Cola, Allstate, Ketel One, Mastercard, Sears, and United Airlines, among others. Sales of the eponymous “Arnold Palmer” drink, distributed by Arizona, reached more than $200 million per year in 2015.

The proof is in the punch. In his playing career, Palmer earned barely more than $2 million in winnings. Today, his estate is worth an estimated $700 million. Not bad for a kid who, in his own words, “grew up poor on the edge of a golf course.”

“Instead of a mere commodity,” McCormack once said of his shining star, “he became an immortal in alligator shoes.”