As we turned off the highway and made our way up the dirt road separating the farm and a faded grey silo, the stench smothered the car like a blanket of gas.

The foul aroma was unmistakable: chicken shit.

Here was the famed course I’d heard folktales about, one you won’t find on any Top 100 lists but that is extraordinary in its own right. As we approached, the holes didn’t so much appear as form, fully and suddenly.

The Halifax Holes — three greens, 11 tee boxes and 18 holes measuring 5,716 yards — sit on 17 acres of Gaddis Farms property in Bolton, a tiny town (pop. 567) in western Mississippi. Gaddis Farms, which dates to 1895, is one of a dwindling number of major farming operations in the state, with 20 employees, producing livestock, soybeans, cotton, corn and, since 1970…golf.

My brother Henry and I eased up a dirt driveway to the course and parked in the grass, among clusters of new pickup trucks and old farm machinery.

There is no clubhouse at Halifax. The course doesn’t show up on Google Maps. It seems neither public nor private. You just kind of show up — if you are lucky enough to know someone who knows about it. Our invite, plus a marked location, came from my friend Tripp. He had advised us to bring a stocked cooler and ditch the collared shirts.

Henry said that it all felt like entering a running country poker game.

The property is rustic, all right. As recently as the 1960s, Gaddis farm crops were still plowed by mules. The animals were housed in a tin-roof barn and grazed in a sloping 10-acre lot on the main part of the property. But as America steamrolled into the modern age, two things happened that altered the Gaddis landscape for good: technology drove out the mules, and Ted Kendall III played golf for the first time.

Ted Kendall III, now 85 and chairman of Gaddis Farms, grew up in the capital city of Jackson in the 1940s, the son of a Depression-era banker. He knew little about golf.

“My daddy thought golfers were evil people,” Kendall says now, laughing.

Kendall’s mother’s family ran Gaddis Farms and a hardware store in Bolton. As a kid, he worked the farm on weekends, and later earned a degree in agriculture from Mississippi State University.

He met his future wife Mary on Bourbon Street in New Orleans during a Mississippi State-Tulane football weekend. Their meeting set Halifax history on its course. Mary was a golfer, born into a family of golfers and raised on a course in Anniston, Ala.

Kendall would soon be initiated to the game, whether or not he wanted to be.

“I was taking a Sunday afternoon nap here one time and she said, ‘You want to go with us to Raymond (Eagle Ridge C.C., in Raymond, Miss.) to play golf? I agreed to go but I wasn’t going to play. Well, I couldn’t stand just watching. I said, ‘Look, give me a ball.’ I hit it so poor and never found it…but I got the bug.”

We just made the course to fit what we had available, and it worked. Ted Kendall III

Close family and friends say once Kendall was hooked, he soon tired of the travel and time it took to play. Necessity became the mother of Halifax’s invention. Kendall maintains that once the farm no longer needed mules, they simply needed to do something with their former grazing lot.

“First, we planted pecan trees,” he says. “But then we got to looking at it and said, ‘Let’s just build a couple of greens here.’ We were having to mow it anyway.”

The Halifax wheels were in motion. Kendall’s crew already knew how to work the land, having farmed the area for generations. They consulted Mississippi State University’s turf management team on course maintenance, and assembled green mowers and other machines used, borrowed and converted. The routing of the course proved more foreign. Kendall insists there wasn’t much of a plan with the layout, just some “slapped down tee boxes.”

The original Halifax Holes opened in 1970. But the twin engines of industry and progress would again alter the landscape. Car traffic grew on a road that ran through the course. So did the distance of the modern golf ball — making the road in the middle of the course untenable.

“Golf got better and the traffic got worse,” Kendall wryly sums up.

In 2000, Gaddis Farms purchased seven more acres of land adjacent to the old mule lot, built a new third green and rerouted the course. They then had to account for the pecan trees that had grown too large for the new layout.

“We got that big old digger and moved them to an orchard back on the other side of the road,” Kendall says. “We left some for the golf course, but moved most of them out of the fairways. We just made this to fit what we had available, and it worked.”

I knew of Halifax from the tales of its Calcutta throwdowns: beer-filled golf and gambling fests, eight to a group of big-hitting cowboys shooting 64-74 on the same Saturday, through a case of Michelob Ultra and half as many double bogeys. Roy McAvoy’s field of dreams.

I cracked a beer and began my weighted Momentus warm-up, not yet trusting the carefree ethos. Tripp arrived a few minutes later.

“Just grab cart No. 1,” he said. “That’s the one he said to get.”

Tripp wore shorts and a faded gray t-shirt. I had come in the requisite golf ensemble; I hadn’t taken his recommendation seriously. But standing next to an open equipment shed with a few white fold-up tables and a box of scorecards, framed by a farm and the expanding Southern sky, I began to understand. I untucked my shirt with the fresh exhale of freedom, like Andy Dufresne with a 5-iron.

Soon, Mr. Kendall rolled up in his personal cart to greet us. He wore a True South Classic polo and a white Halifax hat. A soothing drawl dripped out, slow as the delta.

Kendall welcomed us with warm authority, exchanging with Tripp the easy chuckles of insiders. I introduced myself with unusual temerity. There may not have been a green fee at Halifax, but I sensed this meeting was integral to our welcome.

“Thank you for having us out,” I managed.

From his cart, Kendall surveyed the course. He advised us that the last group was “on number 16,” and that we should just fall in behind them so we would have “room to play.” I had no idea how either was possible on a three-green course. My uncertainty must have been palpable.

“Y’all know the layout okay and where to go?” Kendall asked.

I looked at Tripp with the deference of a partner in his pocket.

Halifax is open seven days a week for play: the course can hold up to 24 players at a time. There are no greens fees, dues or formal organization, just 19 “members” who have purchased carts that stay on the property and who can play anytime. Guest play works exclusively on the invite system.

“Anybody that plays needs to have permission from someone who’s a member,” Kendall said. “I encourage if you’re not playing with the member, sign the book. We have some people take advantage of it a little bit, but it works out pretty good.”

The Halifax Holes are part of the Gaddis Farms operating budget. The course stages a number of fundraising tournaments each year that benefit local youth organizations, and some that raise money for the course itself. Kendall is a bit coy on the exact costs to operate the course, and his board’s feelings about it. He only offers the familiar mantra that they make it work.

Farm employees handle most of the maintenance; a single worker mows the greens three times a week, the fairways once. Occasionally, heavy rain or more important farm duties keep the fairways from being mowed at all.

“The farm collides a lot with the golf course,” said Whit Kendall, Ted’s 27-year-old grandson and caretaker-in-waiting at Halifax.

“Mechanic-ing” is the main thing. At Halifax, the assortment of used and ancient machinery is only as reliable as the hands that keep them running. Both Kendalls credit farm mechanic Dennis Mason as the real magician who makes Halifax possible.

Yet the place has a way of nurturing itself. Last year, the green closest to the Kendall house was infected with a fungus as stubborn as the mules that used to call the pasture home.

“The story of how that green was fixed kind of sums up the whole golf course to me,” Whit said. “When places die, we just get sod from (the practice green) across the road. But we needed help digging and moving it. Now listen, sod work is terrible. But we put the word out and 15, 20 people showed up to help. I thought it was going to take weeks and we did it in a day and a half.”

Whit pointed out three wooden golf tees wedged as spacers into the wiring of the gang mower, hitched to the back of a rusted green tractor with more than 4,000 miles logged.

He smiled.

“We make it work.”

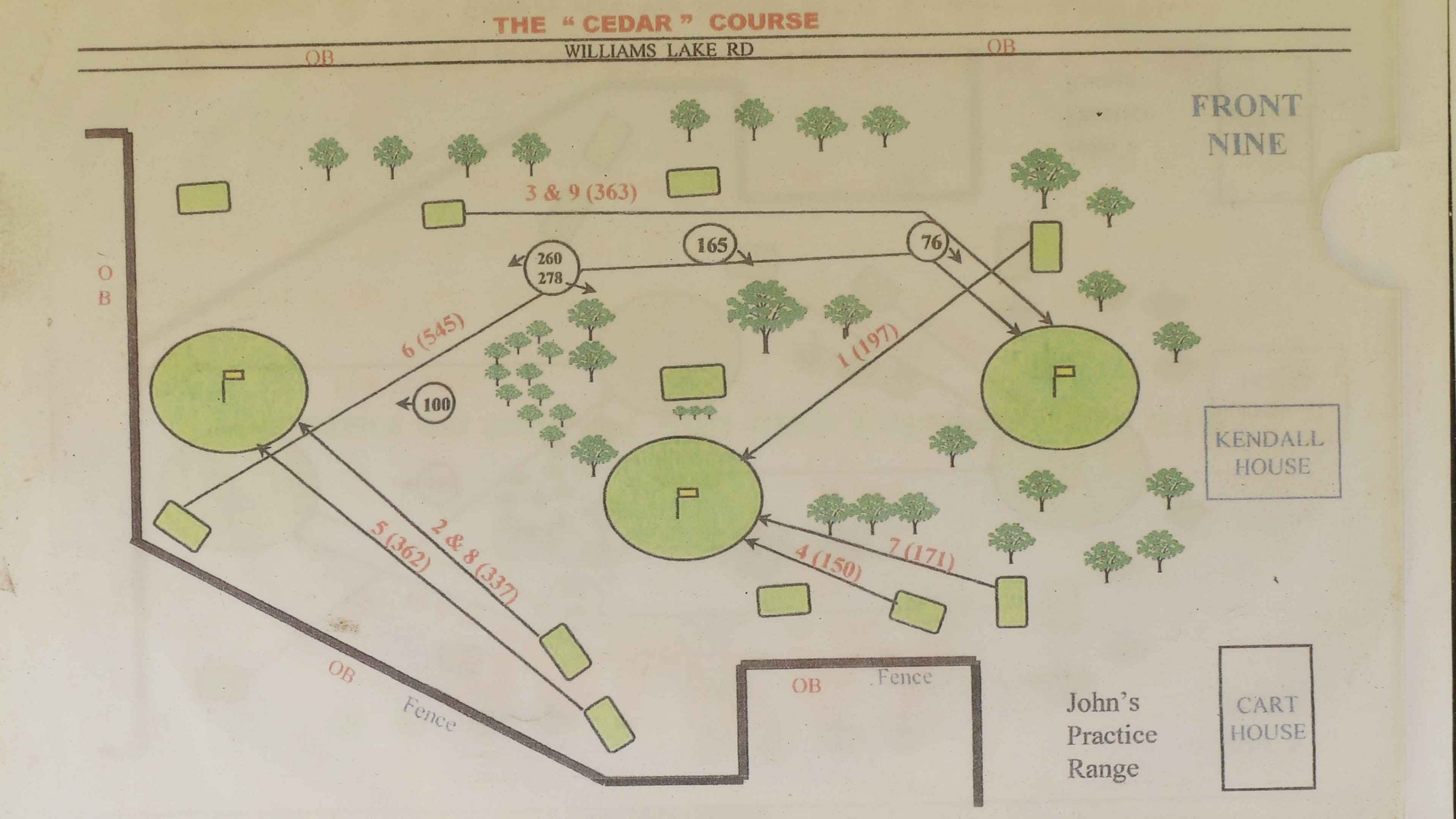

The Halifax layout is a bit of a paradox: ordinary and ingenious, probing yet repetitive. A single pasture contains the full course, sloping down into a grove of pecan trees and rising again toward the horizon. Small tee boxes flank the greens on all sides, most just a few paces off of the putting area.

Each of the 11 tee boxes bears multiple markers to denote their different holes. Some are written on paper and attached to wire fixtures. Many of them seemed out of place or missing. The carts supposedly contained course diagrams, but ours didn’t. This was a place you inevitably just had to know which tee to go to, which green to play.

This was a place you inevitably just had to know which tee to go to, which green to play.

After a solid opening iron shot, I struggled to hit the farm. Most of the tee shots welcomed a full-send to a wide expanse; a few incorporating the pecan trees were tight and awkward. I hit drives that snapped like Randy Johnson sliders beyond the barbed-wire fence, but I didn’t bother to look for them.

We played six par-3s over the par-68 course. I marveled as Tripp and his friend hit the piercing shots of pros. My bogey-golfer brother made two straight birdies, keeping our “Wolf” game close.

Two par-5s materialized. Both spanned the full pasture, requiring a second shot over or around the trees in the middle. I learned on these holes that you could play to any area of the property, so long as you didn’t hit into anyone and could manage the next shot from there. There is no playing through at Halifax.

The course was in impressive shape, with nicer conditions than your standard municipal, but a simpler layout than I had imagined.

Halifax is most aptly characterized by what it wasn’t: namely, complicated. The design encourages the democracy of the game. It’s hard to lose a ball over the open pasture. The small, unguarded greens and lack of rough neutralized advantages. My mishits ran a mile. My playing partners’ towering iron shots often missed. It seemed we would all end up with a chip and a chance.

Kendall never did get good at golf. He kept clubs in his pickup truck over the years, and would “sneak around” taking lessons, but he assures like a proverb that “if you’re no good early and young, you’re really no good old.”

These days, he hits around 10 balls a year. But the Halifax Holes have become his dominion. The course’s calendar highlights are The Bolton Open and The Halifax Invitational, weekend Calcutta tournaments where Kendall famously sits by the scoreboard and drives up the betting.

The course held its 50th Halifax Invitational last year. Early on, Kendall realized that a literal shotgun start was the only possible way to hold big tournaments. He still begins each tournament with a ceremonial blast from the .410 shotgun he has owned since he was a teenager.

Subtler additions like forward tees happened over time. He seriously considered expanding the course into a development when the casino boom hit nearby Vicksburg in the 1970’s. He figured the gamblers would want a quality course to play, but then wisely concluded that gamblers wanted to gamble, not play golf.

“I’m so thankful I didn’t,” he says. “This has been a lot more fun, a lot easier. We don’t have to worry about the cost as much as we would have with something like that.”

He still begins each tournament with a ceremonial blast from the .410 shotgun he has owned since he was a teenager.

Farm Week has called Halifax “the best kept secret in golf.” But what would happen if the secret got out? Could Halifax ever be something bigger? Something more?

Whit, charged with its future, says no.

“If there were ever another course, we would never touch Halifax,” he says.

The patriarchal Kendall demurs on these bigger subjects. He doesn’t think much about its place in the golf landscape. He doesn’t think it can handle any more people. But he reckons with the past and the future playing out on his three-green golf course all the same.

“Every once in a while it gets a little hectic because I can’t do nearly what I used to,” he says. “But with Witt coming on, I’m looking forward to seeing it continue. A lot of people had a lot of fun out here, a lot of interesting stories to tell.”

As we came to the final stretch of holes, the thought revealed itself as the course had done hours earlier, suddenly and fully formed: Halifax was America’s purest course.

Rural Mississippi and pastoral Scotland are close kin: hilly fields separated by simple fences, with grass grazed to the root in some areas, lush and untamed in others. Country homes every half mile or so, housing livestock farmers long on land and ingenuity.

Centuries ago, those same Scottish farmers created the first golf courses by using different parts of the native land as target areas. I considered the obvious parallels. At Halifax, the land is the course. The greens are sloped by the hills they sit on. Tees are only steps from the putting surfaces. And no rough? Not on account of some faux-links homage or inspired call for playability: Halifax literally is what it is.

My heart sank as we reached the final hole. I remember thinking in that moment that I would never play Halifax alone. But I wouldn’t bring just anyone, either.

This was a place for folks that knew the best and hardest-earned secrets in life. I understood what Mr. Kendall had alluded to hours earlier: the course wasn’t to be played as much as shared. I found myself respecting the humble patch of Bolton farmland as though I were playing Pine Valley or Cypress Point. Fixing divots in a mule lot.

Our money game had remained close, but my play hadn’t improved. I had been of the mind that Halifax’s spirit would inspire a free swing and pure contact: McAvoy’s “strike of character.” But that would not have been Halifax. This was the essence of the game, over three humpback greens in a farmer’s backyard. Simple and fun and difficult as could be.

I wished it wouldn’t end. The Halifax ethos, along with my shaky putting, obliged. I missed a six-footer to keep the bet tied and the game alive. We played on.