Everybody will lose in a ball war, but that’s where we are headed. Cooler, wiser heads need to step up and lean in and they need to do it now. As Don Corleone said in The Godfather, “I hoped we could come here and reason together. And, as a reasonable man, I’m willing to do whatever’s necessary to find a peaceful solution to these problems.” Right on, Don!

The Don Corleone speaks for many of us 90-shooters who play regularly and buy golf balls, watch golf on TV and buy GM cars. (Enough with the Cialis already.) We are the game’s economic engine. We should be heard before this thing gets out of control.

The distance report issued Monday by the R&A and the USGA will be seen by some as an opening salvo in an effort for the governing bodies to change the parameters of the ball. What the release of this report should be is an urgent invitation to get golf’s equivalent of the Five Families to a round table.

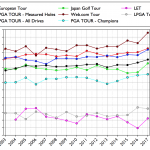

Please allow me to briefly summarize what I found most telling from all the proffered charts in the report. In 1980, a year in which Jack Nicklaus won two majors, the average measured Tour drive went about 256 yards. By 1996, that number had increased by about 10 yards, during the period when Tour players made the radical change from persimmon woods to metal woods. Last year, the average driving distance was up to about 288 yards, meaning there has been a 32-yard gain in 37 years. No one factor can explain it: bigger heads with thinner faces and lighter shafts; bigger golfers swinging harder; faster fairways; longer balls.

Along the way, finesse golf died. (You’ll never see a Larry Mize win a Masters again.) The par-5 as we knew it died. (A three-shot par-5 for a Tour player must be at least 600 yards long in normal conditions.) Golf courses hosting majors became longer and wider. The act of watching a major championship became less intimate. Less Wrigley Field. More Houston Astrodome. Wrigley, by the way, is still beloved. As for the Astrodome, may it rest in peace.

Since 1980 — you can always learn the most from taking a long view — some of golf’s core values, and numbers, have been lost. For decades, a 7,200-yard course for a Tour player was roughly what 410 feet to dead center was in baseball, an established standard. Off a 265-yard drive, a three-shot par-5 of 560 yards was meaningful. At last year’s U.S. Open at Erin Hills, the course measured an obscene 7,700 yards and there were still no true three-shot par-5s for the longest players. (The warm, still conditions didn’t help.)

That’s a problem because the fundamental characteristic of a golf course is that it comprises a series of par-3s, par-4s and par-5s. The intimate, time-tested majesty of Augusta National, Pebble Beach, Oakmont, Shinnecock Hills and various others is rooted in that simple statement. Erin Hills and Chambers Bay had none of that as recent U.S. Open venues. Merion, at the 2013 U.S. Open, was tricked-up almost beyond recognition to make it meaningful at 7,000 yards.

You can follow the money in this distance saga, as per usual. The top executives at Titleist, the dominant golf-ball manufacturer, don’t want to see any restrictions on current ball design standards. As Wally Uihlein, the former Titleist chairman, has told anybody who will listen, it wasn’t just the ball that wrought these distance changes over time. That is no doubt true.

If Augusta National had long, shaggy fairways, it would not have had to Tiger-proof the course after Woods’s 12-shot victory in 1997, played with a Titleist Professional ball. If Augusta’s putting surfaces had the firmness they had when they were Bermuda, the greens would be more challenging for the players and more interesting for the tournament’s millions of spectators. Graphite shafts and thin-faced metal drivers, woods and hybrids have been significant factors in the distance revolution, to say nothing of the size of the driver head and the size (and strength) of the modern player.

But on the other side of the Titleist divide, Woods, who plays a Bridgestone ball, wants to see the ball rolled back. As does Will McGirt, who plays a Srixon ball. As does Jack Nicklaus, a minor player in ball manufacturing. (Ed. note: GOLF’s parent company, Emigrant Capital, is a part-owner of Nicklaus Companies.) Nicklaus doesn’t understand what Titleist is worried about. He told me recently that he believes the company would continue to dominate ball manufacturing regardless of the parameters the governing bodies put on ball design.

O.K.: a long preamble. The USGA and R&A, the PGA of America, Augusta National, the leading professional tours, the ball manufacturers and we the people all have competing interests here. You would be hard-pressed to find a 90-shooter who wants a shorter ball. You would be hard-pressed to find an ordinary fan who thought the Honda tournament or the WGC event in Mexico City would have been any less exciting and interesting had the golfers used balls that went 10 percent shorter.

To prevent a war here over the ball, the families have to identify their common interests. I can actually see only one. The ball manufacturers, the professional tours, the governing bodies and Augusta National, all would like to see one thing: for the game to grow. For any number of reasons, they think the world would be a better place with more golfers.

So how do people get introduced to golf? Your parents might introduce you to the game. Friends might take you to a driving range. Maybe, as a young person, you found work in the game in some capacity. I took up the game through an eighth-grade gym class. But one of the most common ways for the game to attract new fans and players is through tournaments on broadcast TV. Not the week in and week out PGA Tour events. The four majors.

Part of the vast appeal of the majors is to see them played on time-tested architectural treasures, like Pebble and Shinnecock Hills, like Bethpage Black and Pinehurst, like Oakmont and Winged Foot. The creaking clubhouses. The silent galleries. The tense players. The finesse shots from gnarly greenside lies. The weight of history. The knowledge that a player’s life could change if he can shoot 280 (or some other number in that vicinity) and nobody can shoot better.

I think the governing bodies are going to be hard-pressed to find any ordinary weekend golfer who is going to think the game is improved if the ball is rolled back. The game is hard enough. I don’t think week-in, week-out tournament golf is going to be improved if Dustin Johnson can no longer hit the occasional 370-yard drive. But I do think that interest in golf, and the vaunted status of the four majors, would be enriched by having a ball to be used just for the majors. I have made this argument before — here and here. As I made the rounds in South Florida during the Honda and after it, seeing various movers and shakers in the game, I continued to press my argument.

I am saying that the USGA (representing the U.S. Open), the R&A (representing the British Open), officials from Augusta National (representing the Masters) and from the PGA of America (representing the PGA Championship), working in conjunction will the leading ball manufacturers, should come up with design specifications for a thing to be called The Major Ball. Each manufacturer will be welcome to make the ball, which will, in terms of overall flight characteristics, will be significantly rolled back from the regular ball. In other words, only the longest of the longest will hit it more than 300 yards. Maybe it will have more curve in it.

People will say, “Such a ball will favor one style of player over another!” Or “How can you possibly ask players to adjust to a different ball just four times a year at the four biggest events of the year?” So what? Part of the challenge will be to adjust. Really, in terms of the competition, nothing will change. The lowest score will win. (Uihlein did not endorse my idea when I floated it by him last year. “When you land on the specification, let us know,” he said. “Because one type of player will be favored and one type of player will be harmed.”)

But in terms of the message golf sends out on its four holy weeks, much will change. Golf should be played on intimate playing fields, where the fans are close to the players and the tees are close to the preceding greens. Play will be somewhat faster. The shots played will be more exciting. Augusta National will no longer have to constantly contemplate “improvements” that are rooted in new, longer holes. Golf will honor its past every time the players congregate for the four most meaningful championships. The message to all of golf will be an important one: bigger is not always better. If 7,200 is plenty for them, 6,200 is plenty for you. Now’s a good time to get on board. #shorterisbetter

Michael Bamberger may be reached at mbamberger0224@aol.com.