When you’re the boss of a 180-member club that costs $950,000 to join, it would be easy to get lost in the banality of rich-guy golf. Robert Melvin Rubin, a former commodities trader and owner of said club—The Bridge, a stunning, pricey, pale-green playfield down the street from Shinnecock Hills—has no such problem. If you’re looking for a driving-range conversation about how Uber threatens the social fabric of America, Bob Rubin is your man.

He’s 63 and yoga-fit, the lenses on his glasses are smaller than a Kennedy half-dollar, and he’s got that urban flannel-shirt look down cold. (We all wear costumes, don’t we?) At 15, he graduated Exeter, which he attended mostly on scholarship. His father was a Maytag repairman, and his mother was a schoolteacher. Exeter, followed by Yale. These names are being dropped here not as stamps of a high-status education, at least not completely. It was in high school and college that Rubin learned to read broadly and think critically.

He left Wall Street, Rubin once said, “before I started to believe my own bulls—,” and he came to golf in middle age, in the Tiger Era. In the late 1990s, he bought 500 heaving acres in Bridgehampton, on the East End of Long Island, and hired Rees Jones to build a golf course. He knew nothing about golf or real estate. He knew nothing about how to manage the leisure activities of the super-rich, to say nothing of the work habits of caddiemasters. He has learned golf management from the ground up, as one learns all things in golf.

One member was abusing the speed limit on the Bridge’s long, winding entrance drive. (The course, it so happens, was once the site of a twisting, three-mile race course where Rubin raced cars in an earlier life.) That heavy-footed member now must get dropped off on Millstone Road and take a golf cart to the clubhouse. On a drive through residential East Hampton, Rubin once saw a crew of course workers doing landscaping work, in Bridge uniforms, using Bridge maintenance equipment. The equipment made it back home, and Bob Rubin, lefty of the old school, fired the ringleader without compunction.

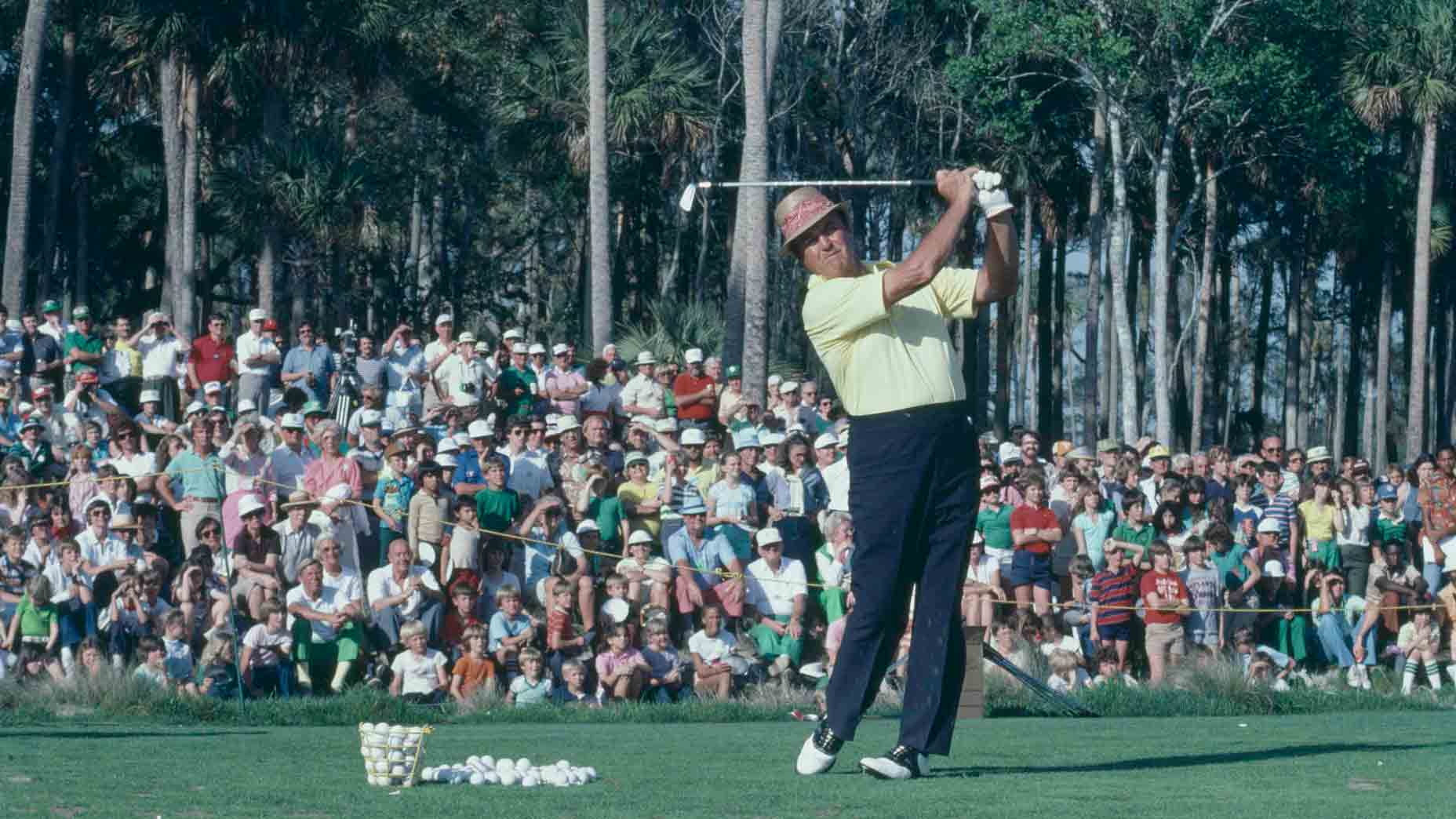

The Bridge is golf and club-life in Rubin’s image. The clubhouse, all windows and wings, may not be your kind of thing, but it’s a modern artwork. There’s an Andy Warhol silkscreen of Jack Nicklaus on a clubhouse wall. On another wall is an album cover for a 1957 LP called “Music for Tired Golfers,” by Larry Clinton and his Orchestra. The fourth track: “Sometimes I’m Happy.”

For his dream foursome, Rubin would gather his artist friend Richard Prince, the late Irish playwright Samuel Beckett and Bob Dylan. Fifteen years ago, Rubin was an uptight 103-shooter. Now he’s a semi-relaxed 92-shooter. Yoga encourages deep breathing. A near-full membership roll does, too. Each year the men’s and women’s champs get their names handwritten on a trophy that vaguely resembles a beer spigot. What, I asked Bob, about a transgender champion? “We’ll drive off that bridge when we get to it,” he said.

This whole discussion is pretty meaningless in the grand scheme. Yes, he built a nice club for a few hundred lucky stiffs. So what? I’d say about the same about Augusta National (but the Masters saves it) and other temples of golf, many of them dear to me. But here it comes, people: Bob Rubin’s Saving Grace (golf division).

He likes the phrase “social condenser.” It’s a term of architecture (one of Rubin’s prime interests), but it could also apply to NBA basketball, as well as Exeter and Yale, as Rubin experienced them—and against the odds, golf at The Bridge. Working with my former Sports Illustrated colleague Farrell Evans, Rubin started an afterschool golf-and-tutoring program in Harlem run by The Bridge Golf Foundation. (Twenty kids and growing, with a second location in the works.) Fresh fruit, TrackMan, laptops, structure. I visited it with Rubin. I wouldn’t call it a social condenser. I’d call it a social condenser incubator.

Recently, Bob and I were driving from Long Island back to Manhattan, and a 14-year-old BGF student, Zion Smith, was on speakerphone, talking (beautifully) about his goals as a golfer and student. He’s been to The Bridge. The people there, he observed, “work hard and play hard.” Bob encouraged him to go to school (and grad school), not just to get a degree “but to learn something.”

In his sleek black Audi, we entered the Queens-Midtown Tunnel. He could picture Zion—smiley, bespectacled—in his mind. The call ended. Bob is like a lot of Type-A personalities, dissatisfied with the state of the world but grateful for the struggle. He said, “That made me happy.”