OCONOMOWOC, Wis. — I posed for a photo here beneath Willie’s Tree, an imposing ancient sentinel that’s just a stone’s throw from Lac La Belle’s serene shoreline. I downed a Coke in Willie’s Pub, whose walls are covered with grainy photos, artifacts, old news clippings and otherwise dripping with history.

Welcome to WillieWorld, as I’m calling it. If you think of a catchier, more marketable name, please pass it along.

The reborn La Belle Golf Club, formerly Lac La Belle Country Club, is paying tribute to Willie Anderson, a turn-of-the-century Scottish immigrant who became a four-time U.S. Open champion, and celebrating a historic connection to early American golf it only recently discovered.

It is a tribute that has been 115 years in the making. It turns out that Anderson and Alex Smith, another Scottish immigrant, were club professionals at La Belle. Smith worked at the club in 1897 and ’98 and may have designed the original nine-hole course. Anderson was hired to give lessons in 1900.

Both went on to greatness. Anderson is the only golfer to win three Opens in a row (1903-1905) and one of only a quartet who captured four. Smith was the Open champion in 1906 and 1910, and in 1901 he lost in a playoff to Anderson by one stroke.

What are the odds that two legendary names in U.S. Open history would pass through the same club in a sleepy Wisconsin resort town? La Belle GC is 40 miles west of Milwaukee and was known as Oconomowoc Golf Club until a name change in 1925. The odds must be even higher of such an historic connection being completely forgotten.

“People can’t believe it,” says John Meunier, who became La Belle’s co-owner and general manager in 2015. “Members who have been here 30 or 40 years are saying, ‘How did we not know about this?’”

That’s a good question. Anderson’s Open legacy was so old that it was largely forgotten too, until Curtis Strange successfully defended his U.S. Open championship in 1989 and said, “Move over, Ben,” an homage to Ben Hogan, the last golfer to win the Open in back-to-back years (1950 and ’51). Strange went for three in a row at Medinah in 1990, sparking a slew of stories on Anderson’s 85-year-old record. Strange was two shots back heading into the final round before fading to a 21st place finish, so he never got to say, “Move over, Willie.” But his gutsy chase cast new light on Anderson.

Twenty-five years later, Meunier and Frank Romano bought La Belle Golf Club from an operator who went bust running it as a public course under a different name. The last thing they expected in the deal was a pair of giftwrapped antique U.S. Open champions. Call them smart shoppers.

Meunier was born and raised in Oconomowoc, and his parents were long-time Lac La Belle CC members. He grew up playing golf on the tight, tree-lined track. That he is now the co-owner and general manager of the semiprivate course, he admits, “is pretty neat.”

He stands behind the bar in Willie’s Pub, the room that was redecorated and renamed in Anderson’s honor, and pours me the aforementioned Coke before telling me the story of how Willie was lost and found. Less than two weeks after Meunier took ownership, a friend stopped by and told him, “It must be pretty cool to own a place where a four-time U.S. Open champion was the pro.”

A startled Meunier gave the visitor a blank stare. “What the hell are you talking about?” he asked.

“I’m talking about Willie Anderson,” the buddy replied. “Willie who?” Meunier asked.

The buddy’s father had been a club member since 1950 and was familiar with Anderson’s connection to Lac Le Belle. Meunier began calling friends of his own father who were long-time members. “They were all like, Willie Anderson—what are you talking about?” Meunier said. “They never knew.”

One member produced the club’s 100th anniversary yearbook from 1996. There was no mention of Anderson or Smith. A mystery was unfolding.

Meunier first went back to his buddy’s 80-year-old dad. “Yes, I knew about Willie,” the elderly gentleman confirmed, “but hardly anybody else did.”

Meunier told Mike Kopacz, a retired friend, about Willie’s connection. “You’ve gotta be kidding me!” said Kopacz, who promptly took on the role of club historian and began sifting through old newspaper files.

“It was like peeling layers off an onion,” Kopacz says. “You’d only get a little bit of information at a time. It made me want more. It made me keep digging.”

The search turned into a journey. Kopacz eventually found a clipping from the Oconomowoc Republican dated June 1, 1900, announcing that the club was opening for the summer. The last sentence said: “The club has secured as golf instructor Mr. W.L. Anderson, who has a national reputation and is considered one of the best players in the United States.”

Anderson boarded with a family in a home adjacent to the course for his year in paradise. The area was popular with business barons from Chicago, St. Louis and Milwaukee looking to escape the summer heat. But he didn’t stick around for long. Anderson was affiliated with 10 clubs in 14 years, including two at historic Baltusrol.

“All the pros in that era were vagabonds,” Kopacz says. “They made their money mostly by teaching and making clubs.”

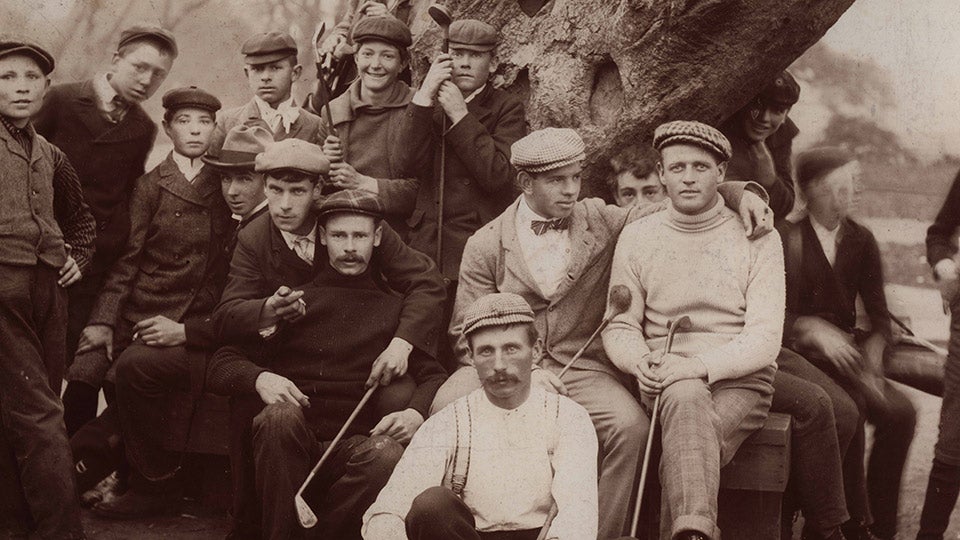

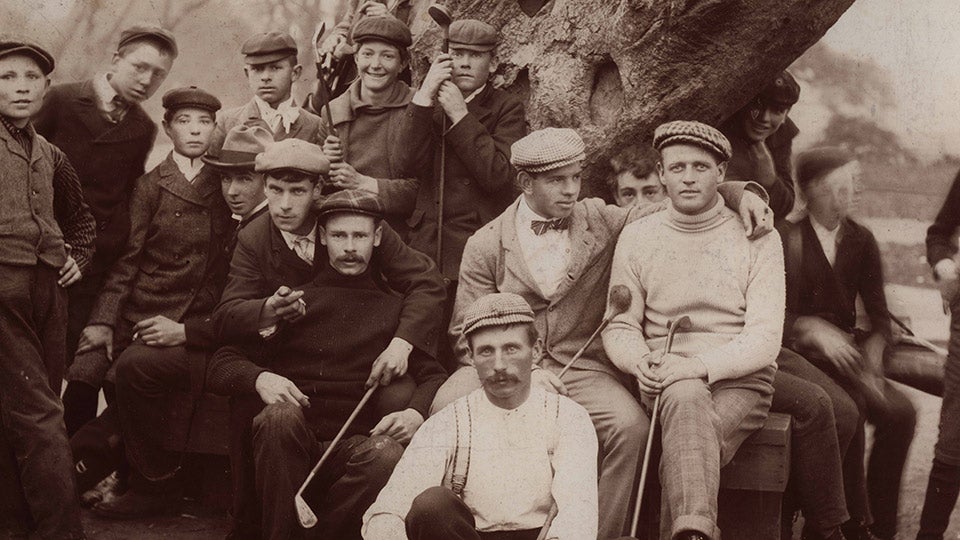

One of the murals in Willie’s pub is of Anderson and friends standing near a large, thick tree. Could it be the silver maple located near the 15th tee dubbed Willie’s Tree, which is estimated to be 225 years old and has a trunk that is six feet in diameter? Maybe. A plaque honoring Anderson sits near the tree’s sprawling base. Surely Willie must have caught some shade there, just as I did, to take in a cooling lake breeze 116 summers ago. Imagine.

“There’s a good chance that picture was taken here,” Kopacz says, “but we don’t know for sure. They used to have invitationals, and pros would play for a first prize of $300. A lot of top pros played here.”

Anderson wasn’t the only lost branch of the La Belle family tree. Ernie Lawrence, another friend, discovered Alex Smith during his research. The 1899 Official Golf Guide listed Smith as the club’s pro in 1897 and ’98, said he designed the original nine-hole La Belle layout and shot the course record, 32. It was a remarkable find. “Nobody in this area knew about Alex Smith,” Kopacz says. “Nobody.” However, the 1900 Official Golf Guide credited William Marshal as course designer and curiously listed the course record as Robert Simpson’s 35. The 1901 Golfer’s Green Book compromised, naming both Marshall and Smith as course architects. Who laid out the holes? Who had the course record? The answers to those questions appear lost in time.

Smith does have a connection to a U.S. Open mark. His brother, Willie, won the 1899 U.S. Open. So consider this: Starting in 1901, the Men of La Belle, Anderson and Alex Smith, possessed the U.S. Open trophy for five of six years. That’s dynastic. Willie Anderson is part of another record yet unequaled. He and his brother, Tom Jr., and their father, Tom, all competed in the 1903 U.S. Open at Baltusrol, most likely the only time a father and multiple sons played in the same major championship. Anderson is also believed to be the only golfer to win the U.S. Open using two kinds of golf balls. He prevailed at the 1901 Open with the gutta percha. He played the Haskell wound ball in his ’03 victory.

Because Anderson won his four Opens on three courses, Meunier obtained flags from Myopia Hunt Club (Willie won twice there), Baltusrol and Glenview. They are framed and hanging in Willie’s Pub.

Anderson was apparently aware of his Open legacy. In 1910 he took a job at the Philadelphia Cricket Club, presumably to pick up some course knowledge and gain an edge for the 1910 U.S. Open. He reportedly wasn’t feeling well at that Open, and he finished 11th. Alex Smith won.

A few months later, Anderson was dead at 31. It originally was reported that he died of arteriosclerosis, hardening of the arteries from alcoholism. “We corresponded with Doug Seaton, a Scottish golf historian, and he vehemently defended Willie’s honor,” Kopacz says. “He swore that Willie didn’t die of alcoholism and he wasn’t an alcoholic.” The death certificate listed epilepsy as the cause.

Either way, Meunier concluded that the bar at La Belle should be renamed in Anderson’s honor, and the room turned into an Anderson-Smith Museum. Before I arrived on this morning, Kopacz found a visitor exploring artifacts in the hallway. “He said he played here 60 years ago, grew up here and now lives in Texas,” Kopacz said. “He was here to play golf, but he heard about Willie and wanted to see the pub. A lot of first-time customers check in at the pro shop, then come down here to look around before they go to the 1st tee. Which is pretty neat.”

Among other items on display is a replica of Anderson’s plaque at the World Golf Hall of Fame in St. Augustine, Fla., which the club got permission to reproduce, and old photos that show Anderson giving a lesson and ladies playing in front of the stunning original clubhouse.

“This is pretty amazing,” Meunier says, looking around at the relics in Willie’s Pub. “A lot of clubs would pay good money to have history like this.”

It takes years to create such history. Sometimes it takes almost as long to find it again.