A quick question for you golfers out there: Who have you logged the most rounds with? An easy one for me. I’m slouched low in the theater’s first row and my answer is filling the screen, standing on a movie-land 1st tee, his bright blue eyes watery in the cool of 8 a.m., giveaway baseball hat covering the top of his bald head. He’s wearing a TV mobster’s windbreaker, long polyester shorts and sheer black businessman socks. His matching golf shoes are untied and he’s dragging the plastic tips of their waxed laces through the morning dew. The scorecard in his back pocket is semi-lodged at best and you can only wonder when it will fall out. He has his driver in his tanned hands and he’s ready to go, or ready as he’ll ever be, anyway. My golf partner, Fred. Or, to borrow the sign-off he used on a hundred voicemail messages, “FRED!” It’s like he never left.

A golf partner is different from a tennis partner or a business partner or a law partner. Of that foursome, only your golf partner is always rooting for you. Through the rounds and over the years, your golf partner — your Fred — becomes some other thing. It’s all those outdoor hours together. The shared pain of duffed shots. The teamwork of a genuine ball-search. The empathetic handshake on the home green. You’ve endured something together, and it could have been better.

Then you retreat, together in spirit if not in fact, to the grill room, the locker room, the parking lot. To weddings and baby-namings. Graduation parties and retirement dinners. Hospital rooms. Etc.

Fred left an impression wherever he went, in golf and beyond her green borders. His gravelly voice announced his arrival and he left a trail of exclamation marks in his wake. (“What a putt! Have you been practicing!?”) Fred wasn’t intentionally funny but his candor — his pathological truthfulness — often contained trace amounts of accidental humor.

Fred lived in Philadelphia, where I live. I asked him once what he thought of our Pennsylvania governor, Tom Wolf, who is a Democrat. Fred was not. He played golf with just about every prominent Republican in Pennsylvania who knew the difference between a pitch shot and a chip.

“I don’t like him,” Fred said.

“Why not?” I asked.

“He’s an idealist!”

It was my typing life that got me to Fred. Fred had a sustained interest in reporters, columnists and writers. He once said, of one of my books, “I read more of that one than any of your others.” He enjoyed his many rounds with my friend Bob Warner, a political reporter, because Bob has a grind-it-out quality that Fred admired. Fred once said of him, “Bob cares.” Fred was looking in a full-length mirror. Fred cared. Like Nicklaus, Fred couldn’t play a shot and not care. Ninety-plus times per round, Fred cared.

In 1992, as chairman of a group called the Pennsylvania Society, Fred wanted to give John Updike, a native son of Pennsylvania, the society’s grand annual prize, its Gold Medal. Fred had me help him write a letter to Updike, to broach the subject, only to find out that Updike’s work and life had at best limited impact on his fellow board members. As it turned out, Updike wasn’t interested anyhow. Responding to Fred’s letter, Updike wrote that, since his mother was dead and his 40th high-school reunion had come and gone, he saw no reason to leave his Massachusetts home and head south to collect the award, which would cost him a weekend and whatever time he’d spend working on his speech. (As a rejection, the letter was firm, but had more hand-typed charm than I am conveying here.) Bill Cosby received the Gold Medal instead that year. Fred was unimpressed. He said then that Cosby made ridiculous demands and that his speech was a mumble.

Fred spent years regretting that he could not sign up Updike for the prize or even get him to accept an invitation to play at Pine Valley, where Fred enjoyed a membership. Fred liked Updike’s golf writing and also his novels about chilly suburban American marriages marked by infidelity. More than anything, Fred liked the idea of Updike. He was amazed that I had played once with him, at Updike’s home club, Myopia Hunt, in Boston’s remote and brackish northern suburbs. I told Fred all about it.

I once asked Fred if he ever thought about becoming a writer.

“No!” Fred said.

I asked why not.

“Too time-intensive!” he said.

***

Fred’s first impulse, always, was to be short and direct. That might give you the wrong idea. Only over time could you see how nuanced he was, how sophisticated and intelligent, how devoted he was to improvement, as golfer and man. He worked at both. As a coffee-shop philosopher and logician, he was a natural.

In his prime, Fred was a Republican kingmaker in eastern Pennsylvania and Harrisburg. He spoke often of the role of power in life, his own and others. We saw the world through different glasses. If I told Fred that I had interviewed Jack Nicklaus in his office for a story, Fred would say, “That’s power!” That idea was foreign to me. Distasteful, really. I would say I made it to Nicklaus’s office because he trusts me and feels that talking to reporters is part of his job. Maybe I’m naïve. Maybe Fred had it right. In any event, Fred accumulated power by getting to know everybody he needed to know (often through golf) and never asking anybody for anything. Or seldom, anyway. He did ask me about a path to Augusta National’s 1st tee, after his guy there died.

But despite Fred’s public life as a conservative, his private political views were largely progressive. He actually became more liberal as he grew older, all while clinging to the chauvinist tendencies of the 1940s and ’50s, the decades when he came of age. He played about as much golf as Arnold Palmer, and all over the world, neglecting his family life when it suited him. Still, he enjoyed excellent relationships with his son and daughter. When they learned, years after the fact, that their father had been playing golf both times their mother was in the delivery room, they were not surprised or upset. For one thing, you really wouldn’t want Fred in a delivery room. For another, they understood their father’s priorities, and that golf was a useful and likely necessary outlet for his addictive and obsessive tendencies.

He cheerfully admitted to having a golf obsession. Fred hitchhiked from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh in order to watch Hogan in the U.S. Open at Oakmont. Even in 1953, that was not normal behavior. There are no pictures of Fred from that day, but it’s easy to imagine the scene, the tall and gangly Fred — in his last year as a teenager, when his large and oblong head still had a lot of hair on its top — standing on the side of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, his thumb out and up with unabashed enthusiasm.

Fred was in college at the time. Fred’s father was a mail clerk on the Pennsylvania Railroad and a golf buff. Fred’s mother ran the sturdy family home and raised Fred and his sister. (Working-class prosperity on newish Yale Road in Havertown, Pa.) As a young teenager, Fred was already trapped in the game’s web. In June 1950, as a 16-year-old, he caddied in the U.S. Open at Merion, for Lawson Little, and watched Ben Hogan hit each of his 69 carry-the-day shots in the Sunday three-man playoff. Merion was a classroom for Fred, both its dank subterranean caddie pen and its two courses. He learned manners at Merion. Also politics, downhill putting and hangover cures. How to tip and how to play ready-golf. How to be a golf partner.

He also learned, as caddies do, the value of keeping your eyes and ears open and your mouth shut. He carried his Merion experiences and his many other golf experiences — most but not all of them good — right through his mysterious death, which even now, more than a year after the event, still troubles me. That picture — Fred, dead — haunts me. It fills a screen, too.

***

Fred — Frederick William Anton III, born March 4, 1934 — was, in ways, like a surrogate father to me, but not in the way people typically use that overwrought phrase. For one thing, my own father, dissimilar to Fred in almost every way, has shaped my life immeasurably. (They met once and that went well. It was at a reading for a play I had written. My parents encouraged my interest in writing. It was Fred who got my play to a producer.) Fred, though he was 26 years older than I, was never one to give “fatherly advice,” not to me, not intentionally. What he did was dig deep into his experiences — in politics and business and golf, in marriage and out, as a drinker and an abstainer — with ruthless honesty, and try to sort through their meanings. My hobby is listening, so we were a good match.

Our breakfasts, once or twice a month, would sometimes last two hours or longer. I can recall one breakfast, after the two-hour mark had come and gone, when I started fishing around for quarters, for the parking meter. Fred said, “Don’t worry about the meter. I’ll pay for the ticket. I want to finish this point!” I can’t recall the point, but it was likely original. At another breakfast, he said, “I seek average returns.” That’s the best financial advice I have ever received.

We always dissected some aspect of golf, though we seldom talked about our own play, just as hospital patients, sharing a room, don’t discuss their ailments. If we did talk about our own golf, it typically concerned our availability to play in the coming days. Most of our games were organized with little notice. This is an approximation of a repeating evening phone conversation.

“Hi, Fred. Tomorrow looks—”

“Yes. When and where?”

Note the order of his responses.

Fred would not be at all offended if you called him a golf bum. He used the phrase himself, without irony. If I went a week in summer without playing (very seldom), Fred might say, “What kind of golf bum are you?” A failing one.

As a freshman at Villanova, Fred sought to start a golf team. He made an appointment to see the school’s legendary athletic director, Jumbo Elliott.

“What can you guys shoot?” Jumbo asked.

“We can break 90,” Fred said.

“Come back when you can break 80,” Jumbo said.

Fred started the team anyhow.

The team played its home matches at Aronimink, a sprawling, old-time Main Line country club, loaded with Catholic wealth. Such private-club religious distinctions were common in the 1950s. Years later, Fred (by then a lapsed Catholic) joined Aronimink. When he dropped out of the club some years later, he said, “The membership there is no longer useful to me.” From another person it would have been an appalling admission, but it wasn’t from Fred. Part of his odd charm.

There was one course where Fred, at his schoolboy best, could break 80 semi-regularly, and that was the short elegant West Course at Merion, typically played by kids, ladies and old men. The West Course is an antique, not even 6,000 yards long, a par-70 with two short par-5s. Merion caddies could play all the golf they wanted to there. From the late 1940s through the early 1960s, Fred caddied on the famous East Course and played the West.

That is, all through high school (class of ’51 at Haverford High), college (class of ’55 at Villanova), law school (class of ’58 at Villanova) and into his early years as a Philadelphia lawyer. He could have played a thousand rounds there, maybe more. One summer, in the early 1950s, Fred won Merion’s caddie tournament, held on the West. I should point out, before you get to this next part, that Fred wanted me to write this obit (assuming I survived him) and he was OK with me using this story from that long-ago caddie tournament.

“There was an assistant caddiemaster there with a mental handicap,” Fred said. “I beat him by a shot. He looked me in the eye and said, ‘Did you hole ‘em all out?’ I said I had but he knew I hadn’t.” Fred told me this bit of personal sporting and social history, which he did more than once, not with shame but certainly not as a joke, either. He could remember the missed short putt he decided, after the fact, to give himself. He still carried that miss with him, all those decades later. His tone was matter-of-fact. He knew he could not undo what he had done and it would be presumptuous to say he wanted to. The reality is, as a teenager like many other teenagers, Fred wasn’t ready to accept that missed short putt or to answer truthfully the heart-of-the-matter question put to him. By the time he shared the story with me, as a man far beyond middle age, there was no remedy.

The point is that he was aware of his own flawed character. That put Fred ahead of most people, or, maybe I should say, ahead of me. He had all the power in that situation and he took advantage of it. He knew he would reap benefits from his dishonesty, and he did. Higher caddie-yard status as the main thing, stained though his victory was. This story revealed Fred’s blind lust for status. Other stories revealed other shortcomings. Along the way, and over time, he inspired me to recognize my own flaws and weaknesses and either accept them or try to change. I’ve tried to pass that message on to our kids. You know, own it.

Fred was active. Over his life, he went to hundreds of Eagles, Flyers and Phillies games. He made an annual visit to the Philadelphia Flower Show. He went to plays, concerts and lectures. In the summer of 2016, Fred invited me to hear Jeffrey Toobin, the writer and CNN commentator, speak at the Free Library of Philadelphia, in the basement of its grand and columned home on Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Fred was a regular there. Toobin’s talk was a sellout and we got there early. With Fred, no matter what time you arrived, he was already there. He taught me the pleasures of the early arrival.

Around that time, various newspapers, including the Philadelphia Inquirer, were publishing regular stories detailing sexual abuse by Catholic priests. We were sitting in the auditorium as it filled, Fred on the aisle. (He always had an exit strategy.) With no preamble Fred said, “I think I was molested by a priest as a child. I’m not sure. I’ve blocked it out. If I was, it had no effect on me.” I was stunned into silence.

Within minutes, Toobin came out to discuss his book about Patty Hearst and her forced enlistment in the Symbionese Liberation Army. Fred made his customary eighth-inning departure, before Toobin took his final bow.

When I left the library, I called Mike Donald, the former PGA Tour player and a close friend of mine. Through me, Fred and Mike had become friends, too.

Fred was fascinated by Mike, who was the runner-up in the 1990 U.S. Open. (This is from A.O. Scott’s review of Creed II: “Losing doesn’t make you a better person. It makes you a person.”) At that ’90 Open, played at Medinah, Mike and Hale Irwin were tied after 72 holes. After an 18-hole playoff, they were still tied. From there the playoff went to sudden death and Irwin won on the 1st hole, with a birdie. Fred was opposed to playoffs of any length and felt sudden-death playoffs were downright unfair. He believed that if two players were tied after 72 holes, they should be declared joint winners. Maybe this was all in reaction to his Merion caddie title, I couldn’t say, but this subject was a recurring theme for Fred.

I told Mike what Fred had said at the library. Mike is as insightful as anybody I know. Mike said, “He thinks it had no effect on him.” That comment has stayed with me because it was so unlike Fred, to ignore cause-and-effect. Mike wondered how boyhood molestation by a priest (if that had happened) contributed to Fred’s alcohol abuse as an adult. Fred started his high-volume drinking in college, in the early 1950s. He quit in 1990, when he was 56.

***

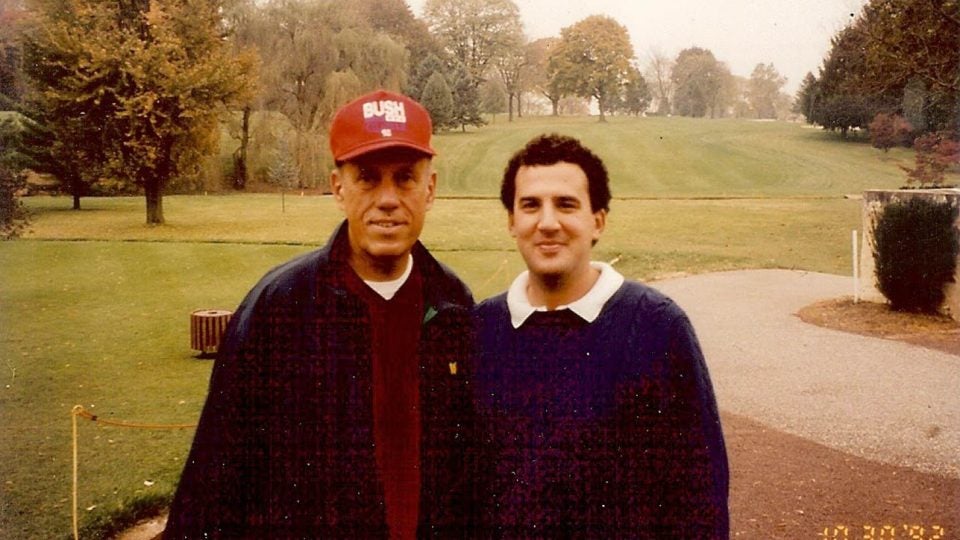

I had met Fred three years earlier, when I was a reporter on The Inquirer, covering high school sports on the Main Line. I had also written a book, about my brief stint as a touring caddie. One weekday afternoon in 1987, I was on Terry Gross’s NPR show, “Fresh Air,” to discuss the book. As I recall I was a last-minute fill-in for David Eisenhower, who scratched. Fred heard the interview and, through a mutual acquaintance, contacted me. (It wasn’t like that was an everyday occurrence.) We talked on the phone, compared some caddying notes and arranged to meet. He said he wanted to buy two-dozen copies of the book, for various Christmas gifts. This was in July.

We met in the parking lot of a Main Line restaurant. I can still recall Fred, this tall, bald paunchy millionaire businessman with big arm gestures, opening the deep trunk of his dark Lincoln just as I was pulling a box of snugly-packed books, straight from the publisher’s warehouse, through the hatch door of my maroon manual-transmission Dodge Omni.

Then, it was day-to-day life unfolding. Looking back, it all seems so unlikely and random. Where would my life be today had Eisenhower showed?

Soon after that book handoff, Fred invited me to play Aronimink. I was perplexed and on guard. I mean, I didn’t know Fred, or what he wanted. But I was excited, too. For one thing, I was playing Aronimink, where the 1962 PGA Championship had been played. Around then, most of my private-club golf came through a Monday tip-the-staff outing group I belonged to called the Philadelphia Newspapermen’s Golf Association. (PNGA rules required its members, all men, to play in trousers, even when the clubs hosting us permitted shorts. Nobody was going to call us golf bums.) We played the West Course at Merion and some other nice places, but kind of on a back-door basis. We changed shoes in the parking lot. Going to Aronimink, as the guest of a member, was another level. And now I was in the club parking lot, looking at its grand clubhouse, airlifted from the English countryside. I remember having no idea which direction to walk.

Fred later told me that our round there was a field test, to see if I could handle other social and golfing situations that promised to be even more challenging. He had two other guests that day, one a sort of ne’er-do-well socialite who played well, the other a construction mogul. I can still recall their names, and I’m terrible with names. One round was in the books. I could never have imagined how many would follow.

Some years later Fred and I played together at a public course called Galen Hall, in far-off Wernersville, Pa. We wanted to see its 15th hole, a par-3 designed by A.W. Tillinghast, with a green surrounded by a moat. It was windy, raw and cold. We decided to play a stroke-play match (total strokes for the round) and not our regular match-play match (each hole as its own contest). Our logic was that either of us could ring up a big number on 15 and the results on that hole should have an outsized influence on the outcome of the day. We didn’t lose any balls in the moat and our match remained close. But then I made some kind of double-digit score on the par-4 16th hole and by the time we holed out on 18 Fred was the easy winner. The stakes were low, but only financially. I heard about my butchery of the 16th for years to come.

Maybe the scorecard from that round survives, tucked away in one of the many journals Fred left behind. This was in March 1995. I wrote-up our Galen Hall visit for The Inquirer and the story ran under the headline “Golf’s Masochists Can Find Water Torture in Pennsylvania.”

***

From the start, Fred paid for nearly everything. Probably not at Galen Hall, but nearly every other time. If I were as honest as Fred, or as relentless, I’d drill deep and explore the uncomfortable truth implied in that. Would our friendship have taken off as it did had Fred not been so generous, if he did not have so much access to the golfing good life? You can guess and so can I. I have learned over the years that “follow the money” is a powerful directive in any investigation.

As is the reporting modus operandi of the late Tom Wolfe, to follow status markers. That is, what will people do to raise their status within their peer group? This works for street-corner drug dealers looking for indoor work, Wall Street titans trying to get into Augusta National, sportswriters seeking literary respectability, among other populations.

I have been slow to learn or accept this, but every friendship after nursery school is a complicated equation of deposits and withdrawals and no relationship is a match-up of exact equals. The starting point of my friendship with Fred was rounds of golf I could not afford on courses I could not sniff. I cringe typing that but I know it’s true.

Of course, you could also say that a real friendship has no ledger at all. How could it? It can’t, as there is no device that can measure how another person makes you feel. Isn’t that at the heart of the mystery and beauty of friendship, how a friend makes you feel, and vice-versa?

This next bit is accurate only in its presentation. Sometimes when I would make an effort, fulsome or otherwise, to pay, Fred would say, “You don’t understand. When I’m with you, you raise my status!” A patently absurd statement. As a low-rung newspaper sportswriter? I wasn’t raising anybody’s status. But Fred seemed to feel otherwise.

Also, Fred had a loose attitude about money. He was, in his view, the overpaid and over-privileged president and chairman of an insurance company, the Pennsylvania Manufacturers Association, and the head of its not-for-profit lobbying arm, the PMA foundation. Fred was not one to hoard money. He gave to charities and politicians, paid caddies generously, took care of, or helped out with, the school tuitions of a healthy number of people connected to him. If a $20 bill fell out of his pocket, and that kind of thing happened with him, he didn’t care, because it meant almost nothing to him and he could guess what it would mean to the person who found it. His attitude, about picking up green fees and the rest, was that the money was a lot for you (for me and the others he “entertained”) and not for him, so who cares?

Over the course of 30 years, I’m guessing we played around 300 times. That makes Fred my No. 1 golf partner, although I was near the bottom of Fred’s top-10. Ahead of me on his list were a couple of his lifelong golf buddies; his weekend regulars at Rolling Green Golf Club; his insurance-executive son (Fred IV); his lawyer and golf-in-the-kingdom traveling companion, Jack May; and his longtime lady friend, Emily Ryan. His partner, in Fred’s obits. Good word.

Fred started seeing Emily after the dissolution of his 25-year marriage in 1990. He helped Emily, a single mother with four children, to finish college, go to law school and begin a career as a lawyer representing abused mothers. Fred also introduced Emily to golf, and she got the bug in the worst way. After several years, Fred said, “I want you to play with Emily — she plays competent golf!” There was pride of authorship in his voice. I did. She was way north of competent.

That’s something, because it’s not easy, to take up golf in midlife. The nuances of the game require many long, slow unrushed days — unrushed summers, ideally — to get baked-in. Emily had far too much going on to bother to learn the odd history of the stymie rule. I’m talking about something elusive and close to meaningless here, fluency in the language, spoken and unspoken, of a peculiar, niche cross-country game. Still, those nuances mattered to Fred.

One of the things he enjoyed most about playing with Mike Donald was Mike’s super-fluency in discussing golf’s rules, players, tournaments and courses. What Mike knew he had learned first-hand, and Fred was the same way. Mike could stand on a green and say, “See, the problem with this green is, it’s got just two pin placements. He’s got 7,000 square feet here and two pins? It’s a joke.” And because Fred understood exactly what all that meant, right down to the multiple meanings of he (the architect who designed the green, the superintendent who maintains it), Mike made Fred feel like he was in the club. It’s a kind of intimacy, really. A good golf partner will make you feel good. Maybe I should have said that earlier, but if you’re a golfer you already knew it.

I recall Fred playing a greenside bunker shot, straight up a hill, from soft, heavy sand. He got his ball out in one and left himself maybe a 30-foot putt. It didn’t look like much of a shot but it was. You needed to open the face and have some speed through the ball.

“Good one, Fred,” I said.

“That’s why I like playing with you, Mike,” Fred said. “Emily doesn’t know what a good shot is. You do!”

That wasn’t a dig at Emily. That was Fred saying, lifer-to-lifer, that he and I were in the same club.

When Mike would make a reference to golfers “hanging around,” Fred got a kick out of that. The phrase could refer to a star golfer on a Sunday leaderboard or a journeyman pro on Friday afternoon wondering what the cut will be. Golf has a lot of hanging around. You’re hanging around the 1st tee, the caddie yard, the grill room bar, waiting for a game, a loop, a drink.

Fred was keenly aware of how soaked in alcohol golf is. He was an expert on the subject. As a teenager, Fred caddied for Tommy Armour at Merion repeatedly and Fred noted that the great Silver Scot, winner of three major championships in the 1920s and ‘30s, “smelled of gin at 9 in the morning.” For years, Fred’s car had a post-round autopilot function that took him to the many Main Line bars where you could talk golf to the barkeep and get good pours. Fred was lucky. He was never arrested, never in a wreck.

He was drawn to drinking, Fred told me more than once, because of his “profound social anxiety.” He blamed that on being tall for his age as a kid and young for his class. He would sometimes say his life would have been different had his mother started him in kindergarten, at their local parish school, at age five instead of four. Not better or worse but different.

May 7, 1990, was a Monday, and the day Fred stopped drinking. He was flying from Augusta to Philadelphia with a change of planes in Charlotte. While waiting for the second leg, he had a beer at an airport bar. That was it. He had been seeing a psychiatrist and they had been talking about Fred’s drinking and its costs and how Fred might quit. Fred put that airport beer down and told himself he was done.

It must have been with a thud. For years and decades, all through his lunches and dinners, Fred had tippled a long series of clear cocktails with baby onions and olives floating in them. I should note, limited though my exposure was, that I never saw Fred stagger out or anything close to that. His conversation was never remotely inappropriate. But the consumption of alcohol was the organizing principle of his life, alongside setting up golf dates. He defined an alcoholic as someone “who is in love with alcohol.” He’d wake up and look forward to his first drink. At the Charlotte airport he was saying goodbye to all that. At least, that was his plan.

He became a Friend of Bill’s, if you know that phrase. (Alcoholics Anonymous was founded by two men, Bill W. and Dr. Bob.) Fred would sometimes tell me that his greatest and most meaningful relationships were with the people in his meetings, people he might know for only a morning. People so unconnected to golf they wouldn’t know the difference between Tim Rosaforte and Tiny Tim.

It wasn’t like he underwent personality-transplant surgery. He was still Fred. But he was different. AA’s Big Book became his bible. The core value of AA, Fred explained, is ruthless honesty about yourself. He never took his sobriety for granted. He would occasionally mention his desire to have a slice of pizza and a beer — he wasn’t fooling himself. He was a true believer in one day at a time. On any given day, I wondered if Fred would make it to the end without ever having another drink.

Fred would often, in our breakfast conversations and by his example, reveal his attachment to the Serenity Prayer, one of the cornerstones of AA: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” Its first word — God — is a moving target, of course, meaning different things to different people. Fred found his god at those AA meetings, along with real companionship, tough love and empathy. But he also found real companionship and the rest in his golf. Rolling Green, his longtime golfing home, was surely more inviting to him than any church, and, in season and deep into fall, Fred was there every Saturday and Sunday, with his regulars. The outstretched palm of a caddiemaster meant more to Fred than any church collection plate ever could.

***

I started playing golf with Fred when he was in his late 50s and played with him regularly all through his 60s, 70s and early 80s. He nearly always had a thorough pre-round warm-up. With a driver in hand, he stood comically close to the ball, with his feet too close together, and he had an upright bent-elbow backswing. He looked like he could topple over at any moment. But with his putter in hand, he was bent over the ball like a beach-walker collecting sea glass. He had a weak grip with every club and there were the purplish stains of age on his hands as he grew old. With the driver, he hit a semi-reliable but short push-fade that often finished in the fairway. He’d grab his 3-wood from his caddie before he left the tee.

He was committed to getting better — or at least holding on to what he had — and generally believed improvement was coming, despite the broad hyper-realism that defined the rest of his life. His blind-spot optimism for his golf made him like every other golfer in the world.

Some golfers talk to their airborne ball. Fred did not, or not often. But he did talk to himself. He’d say, “That’s no good.” Or, “That’s lousy.” Less frequently, “That’s more like it.” These comments came without his customary exclamation marks.

We nearly always played some sort of match and we both knew the rules reasonably well and abandoned them only by joint agreement. As a twosome, walking and holing out on most greens, we typically played in well under three hours for a standard 18-hole round.

I can readily recall one 19-hole day. Pretty much wherever we played, the caddiemasters, starters and assistant pros knew where to send us off, so we, playing quickly, could play unimpeded. (Fred’s custom was to tip upon arrival.) On this particular day, at the Philadelphia Cricket Club, where I have played for years, we started on the 10th hole of the club’s Tillinghast course. The hole is a short par-3, one of the easiest holes on the course, except that starting on a par-3 is never easy. It requires you to begin your day with more precision than you can usually muster. Fred hit a lousy tee shot, followed it with two or three duffs, and picked up. He said, “I’m not counting this hole.” I made a bogey and said, “I’m counting mine.” We then played 11 through 18, went to 1st tee and played the front nine until we were back on the par-3 10th. I was done. Fred, true to his word, was not. He knocked his 150-yard tee shot into the hole and said, “I’m counting it!”

Sometime later he made a strictly kosher hole-in-one at Cypress Point.

“Congratulations, Fred,” I said when he returned. “You made a hole-in-one this year.”

“I made two, I made two!” Fred said.

We had a lot of fun.

***

I should note that our fun was inconsequential, typically just some unexpected thing — what somebody said or saw or did — that tapped his funny bone or mine. I’m sure a lot of this would come under that old standby, Guess You Had To Be There. He once called my car a “jalopy.” That made me laugh. Another time, after I ordered a lunch sandwich with certain unadvertised fixings, Fred said, “It’s not a menu to you — it’s a list of ingredients.” I once joined him when he gave a talk to a group of young Republicans at Philadelphia’s Union League club. He said, “They say that honesty is the best policy. It is. But it’s not the only policy.”

He was a fixture in, and a creature of, the city. People would say hi to him wherever he went. Once or twice a year he would invite Christine (my wife) and me to join Emily and him at various sparkly Philadelphia events. I would sometimes bump into Fred at one of the city’s art-house movie theaters. We have several.

He was a movie buff. We regularly compared notes. We’d go right through the list, clipped out the paper. With some hesitation, I recommended to Fred a morose live-action animated movie called Anomalisa, written by Charlie Kaufman. It features a drinking, disaffected traveling businessman with a large head. In the movie, the man is asked about his hotel room and he says, “It’s boring. Everything is boring.” I feared Fred would like it and he did. He said it captured his view of life. It’s one of those movies that doubles as a pipeline into the question most of us try to avoid: What does it all mean? Fred, in the wake of his sobriety, had made that question his life’s work.

Michael Murphy, the author of Golf in the Kingdom, used to say that golf is yoga for Republicans. It was for Fred. It poses, again and again, the same questions: Can you get your body to do what your mind wants it to do? Can you get your mind to tell your body what to do in the first place? The game really is a riddle, at every level. That’s why I seldom get tired writing about it, and why my golf partnership with Fred grew more meaningful to me with every passing year.

For a this-is-life movie, I go straight to My Dinner with Andre, with particular emphasis on the moment in it when Andre — played by André Gregory, a Jewish theater director with a toe in Buddhism — refers to a thespian version of the Four Questions: “Who am I? Why am I here? Where do I come from? And where am I going?” Fred was asking himself those questions on instinct alone.

Fred had other Jewish friends, long before me and far beyond me. He was interested in Judaism, the cultural aspects for one thing but also the spiritual intensity of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement and the conclusion of the Days of Awe, which begin with Rosh Hashanah. Over the years I received the occasional September call from Fred seeking the same advice: “Mike, I want to call Senator Specter and say the appropriate thing.” (Fred liked the word appropriate.) He’d then make a sincere but off-the-mark attempt at “Happy Rosh Hashanah.”

“You can just say happy new year, Fred.”

“OK, good. That’s better.”

Fred had a long and close relationship with Arlen Specter. Also with Ed Rendell, Tom Ridge, Bob Casey Sr. and Dick Thornburgh, to cite just a handful of notable Pennsylvania politicians. He admired Ron Castille, a Pennsylvania Supreme Court judge who lost his right leg as a Marine in Vietnam.

Fred, briefly a Marine himself, and I played golf once with Castille. The judge had powerful arms, a big turn and, for a one-legged golfer, amazing balance. He was an impressive golfer.

About two months after Trump’s election, Fred and I had lunch with Castille. He talked about John McCain and how Trump had dishonored him. It was a snowy day in Philadelphia and we ate at an empty old-world downtown Italian restaurant, La Famiglia, near Fred’s condo on the Delaware River. It was a regular spot in Fred’s rotation, one of a half-dozen or so restaurants where the owners and waiters knew and liked him and knew not to bring him the wine list.

Castille told us about being on the short list for some unspecified federal position that required Trump’s signature. He described getting in his car and starting a drive of some distance to meet with Trump’s people, then suddenly making a U-turn and heading home. He could not work for Trump. Fred was hanging on every word. He was preoccupied by Trump. He feared that we, as a citizenry, were becoming inured to Trump’s daily outrageousness. I’m not using feared casually.

Years earlier, I had given Fred a running account of my golf games with Trump. But in that period Trump was just a glorified TV game-show host. Yes, the fairways of my stories were littered with his unreliable scorecards, but did it really matter? Trump’s golf undressed him, as golf does, but the stakes were so low. His golf in my telling was a bit. Nobody could have ever guessed that Trump would someday become elected president. Impossible. In the past, in some sense, Fred would have had a line to Jerry Ford, to Reagan, to the Bushes. It was there if he needed it. He didn’t want a line to Trump.

Along the way, he felt that his status, as a man-to-see in Pennsylvania politics, was fading. It probably was, but it was a slow retreat. He remained the chairman of the PMA foundation, his old company’s political arm. Fred continued to have a busy schedule, though less busy than it had been. He didn’t have anything fatal, although he did have some respiratory and stomach issues that were causing him discomfort. He went to doctors but had little faith in them, except, as he put it, “the Jewish psychiatrist I went to see before I stopped drinking.”

***

In his 80s, Fred’s interest in golf, his own game and the professional version, was becoming less intense. He started to play courses from more forward tees, to make them more manageable, but that brought him no joy. He complained about his lack of distance. His best golf was behind him and he knew it. Every golfer’s worst nightmare.

Also, he was playing out of a cart. For an old caddie and a committed walker, that hurt. He regarded golf in a cart as a different, lesser sport, and maybe not a sport at all. But that’s what he was doing. In fact, he was driving the cart right up to his ball. At one point I suggested to Fred that he park the cart some yards from his ball, to get some walking in. In the all the years of our friendship, this was the about only time I could ever say he was really angry with me. “You don’t understand, Michael,” Fred said. “You don’t know the pain I’m in.” I regretted saying anything.

Fred was not usually one to get angry. He had moments of frustration, of course. He got mad, as we all get mad. But mad is just that flash of heat crossing your cheek. It comes and goes. It can give you a burst of energy that may or may not be useful. Anger to me is more like a slow leak, and there’s something self-loathing about it. Long-term, I have found and observed, anger can fuel desire but steal your spirit. I believe that sobriety for Fred, and whatever he found in AA, helped him keep anger at bay.

I think we played once in Florida in March 2017, when he turned 83. (He and Emily had a house in Florida but Fred was seldom there. Florida bored him.) We played some golf, but not a lot, in the spring and summer of ’17, including one game at a short nine-hole course that I enjoy but that Fred dismissed as “Mickey Mouse.” In September 2017 he fell and broke his left arm. It was in a cast. “No golf for six weeks,” he said, no exclamation mark. I can remember calling Fred from lower Manhattan, in late September, on the eve of the World Golf Hall of Fame induction ceremonies there, and him giving me a progress report on his arm. He was down but not out.

A few weeks later, in mid-October, Mike Donald was making a brief visit to Philadelphia. We were going to run (jog) in a Saturday-morning neighborhood race, one of those fundraiser 5Ks, and play golf after it, in a foursome at Pine Valley with two others, a father and his son. I asked Fred if he wanted to join Mike and me for dinner Friday night. He said no. We hung up. Seconds later he called back and said yes. That was out of character. Fred almost never changed his mind, about anything.

I suggested we go to one of his places, another neighborhood Italian restaurant, Radicchio Cafe, a short drive from his condo. Fred was then making plans for elective stomach surgery, after a Main Line surgeon had offered the prospect of relief. In the meantime, Fred was dealing with life as a single man in his eighties with his left arm in a cast. Because of it, Fred could not drive and dressing himself was a struggle as was preparing meals and all the rest. Emily, who had her own home in the suburbs, had temporarily moved in with Fred to help him. I was surprised when Fred told me that, because he so prized his independence. As for Emily, she must be part-saint, because even in the best of times Fred was impatient and demanding. (Whenever he had a caddie take a group picture, his next words were, “Take another!”) I can only imagine him as a patient.

Emily had been driving Fred to his various appointments, and to his AA meetings, but he told me he wasn’t going to them as often has he normally did. That was surprising. He lived for those AA meetings, for their candor and intimacy. Fred would sometimes tell the story of the time a British rock star showed up at one of his meetings and shared with the group how, in the haze of alcohol, he had dropped a TV from the roof of a high-rise hotel. (Fred didn’t take the second A, for anonymous, too seriously.) The final line was, “Who did I think I was,” followed by the rock star’s own name and a question mark. There was underlying violence in the story — the flying glass, the possibility of innocent death — but telling it always made Fred laugh. I never knew how to interpret that. But what was obvious was that AA connected Fred to worlds and lives and even behavior he might otherwise not know. His meetings were not the businessman’s animated hotel room in Anomalisa. They weren’t boring.

Fred would sometimes say I should write about AA. More than once he invited me to join him at an “open meeting,” checking first with the meeting leader that it was OK to have a reporter accompany him. (Drinking is not one of my issues.) For whatever reason, I never took him up on it. I do feel, through Fred and learning about his AA experience, that I became more attuned to the fine line between mental illness and mental health, for any of us.

At one point, Fred arranged for me to see his golf teacher, an old-school pro with a Scottish surname and not much to say. He told me my swing was more like a flail. Maybe it was a Fred-sponsored counseling session. Maybe it was just a golf lesson. Or maybe it was both, as the best golf teachers are secret psychologists, too. (For more on that subject, you might read “The Pro,” a 1966 short story by John Updike.) In any event, Fred was interested in my improvement, too.

I drove to Fred’s condo, to take him to that Friday-night dinner at Radicchio. Emily was at the door. Fred gave me the keys to his XXL BMW, far more commodious for him than my Subaru. He then barked intensely specific directions about which route to take to the restaurant. He had me park right at its front door and he hung a handicap parking hangtag from the rearview mirror. Fred was greeted warmly and we were seated immediately. Mike, walking from his hotel, arrived within minutes. Fred gave Mike some sort of jokey cartoon about the differences between how men and women see relationships. Mike laughed, folded it and put it in his pocket. We talked about politics and golf and some other things. The tables are close together at Radicchio and the two women at the next table over — out-of-towners and, out of character for the place, all done-up — jumped into our Trump conversation, but Fred indicated no interest in engaging them and they quickly retreated.

Over the years, the three of us, sometimes joined by others, have had meals where the conversation was intensely spirited. This dinner was not one of them. But it was fine. It really was. The restaurant had a lively hum and a good smell. Fred picked up the tab and Mike and I knew not to protest. He paid in cash and needed no change, as per usual. Mike walked back to his hotel. Fred and I got back in his car. Fred said, “Maybe you can come in and have some dessert or coffee when we get back.” That was completely out of character. In the 25 or so years he had lived in that condo, I had been in it about three times.

We arrived at his building and entered its covered parking garage. I proceeded to drive his car to his spot, beside his main condo door. He didn’t bring up dessert again and neither did I. Fred said he was glad he decided to come and went inside. Emily came out and thanked me for getting him out of the house.

“How’s he doing with the depression?” I asked. I’m not sure why.

“Not good,” Emily said.

That was on Friday, Oct. 13, 2017.

Late the next afternoon, driving home from Pine Valley, I called Fred. He wanted to know all about the day, how Mike played, the condition of the course, who was there, all of that. He was engaged and curious. Normal Fred. I remember thinking: He’ll get that cast off, he’ll have the stomach surgery, he’ll do some rehab with his trainer and in Florida — he’ll be OK.

Mike once said something like, “You have the kind of relationship with Fred that I had with Gardner.” Gardner Dickinson, a successful tournament player and a disciple of Hogan’s. For years, he had been Mike’s teacher. “When Gardner died, there was no one who could replace him in my life, because there was nobody like him. And when Fred dies, it’ll be the same for you, because there will never be another Fred.”

***

Nov. 1, 2017, was a Wednesday. That afternoon, I got a call from Emily. She said, “Have you seen the man? He’s gone missing.” I had not. I immediately feared the worst.

That night, I received a call from Fred’s cell phone. (Fred on my caller ID was Fred. His son is Fred4.) I was shocked, almost confused, too startled to be relieved. But it was Emily calling from Fred’s phone. He had left behind his phone and wallet. His car was in its usual spot. There were still no signs of Fred.

Thursday morning, I went to Fred’s condo. It was on the ground floor of his boxy, modern building. The building itself was part of a 1990s residential development built on a city pier that juts out and into the wide, murky Delaware River, with its strong currents and muddy banks. But Fred had a great view. Through his large picture windows and sliding glass door, he could see, and almost touch, dozens of boats tied up on a mishmash of docks, sailboats and cabin cruisers, speedboats and houseboats, a boat population that changed with the seasons.

Fred was last seen on that Wednesday, recorded on a security camera as he walked east on the pier, with the boats on his left, heading toward the open river.

I knew many of the books on his shelves. I had either read them or, more commonly, had heard Fred talk about them. I remember his enthusiasm for A Drinking Life, by Pete Hamill, and Drinking: A Love Story, by Caroline Knapp, among others. There were books on philosophy, history, psychology, on baseball and football. He had given away most of his golf books but some remained.

Emily was on a chair, knitting. Sarah, Fred’s daughter, sat on a sofa. Neither faced the water. One of Emily’s sons was there. We talked about — I couldn’t possibly tell you something accurate. A phone would ring now and again, but never with news. We were all waiting. Waiting for something.

Suddenly, with terror on his face, Emily’s son came up to me and said, “Get them out, get them out now.”

Emily, Sarah and I walked out of the condo, not through the sliding door that led to the dock but in the opposite direction, through the main door, the one that led to the covered parking garage. I tried to slow my racing mind. The garage, I noticed, was bright and cheerful, and also, for a parking lot, unusually still and quiet. I asked Sarah and Emily random biographical things about Fred or themselves, or recalled some humorous old episode where Fred made an appearance. Any topic that kept our actual gathered purpose at bay. After being out there for some time, I went inside, to get us something to eat and drink. I was back within two minutes. I could not tell Sarah and Emily what I had seen: Fred’s body, among the docked boats and just beyond his sliding glass door, floating face down. I could see the back of his tanned, bald head, his Lt. Columbo rain jacket fanned out, like a stingray’s fins. But he was still, unmistakably Fred.

Before long, the parking-garage quiet was broken by the hum of a hovering helicopter. “They found him, didn’t they,” Emily said. The three of us hugged. Fred IV arrived. Eventually we all went in.

Fred’s body had been removed and the mechanics of death were in full swing, with a small group of polite, professional men in different city uniforms, from different departments, in charge. It was a death by asphyxiation, by drowning. He left no note. It could have been an accident. But I doubt it. Fred craved control, and he could see where things were going. Still, you wonder: What was he thinking as he walked east on that pier?

He left me with a crowded memory bank. The names of the two guys we played with in our first game together. All those breakfast conversations. That last dinner, with Mike. Our many golf games, in wind and rain, on frost-delay mornings and dog-day afternoons, on perfect spring days when you could actually smell the grass and convince yourself that you could see it growing. Thousands of hours together. What does it all mean? Fred’s question, though he never worded it that way. But that’s what he was chipping away at. Fred cared. Fred tried. Fred cared and tried until the day he died, I’m certain of that.

***

Nov. 1, 2018, was a Thursday. The one-year anniversary of Fred slipping away. Fred IV and I had lunch with two of his father’s contemporaries. We raised a glass to him and, all things considered, had a good time. On the way out, Fred IV gave me a copy of an old journal entry from his father that filled one lined page and half of another. He had been going through his father’s journals. Not systematically, just dipping in, here and there. Fred III had shown me them several times over the years, spiral-bound notebooks, not well-ordered, filled with his considered observations, some of them so personal and direct they were difficult to read, written in cursive that wasn’t doctor scrawl but not Catholic school Palmer Method, either.

The first words on the first page are Dear Mike, but I’m not sure it’s really a letter. For one thing, it’s unsigned. For another, Fred never sent it or even told me about it. He was writing about a 1996 SI story I had written about the Cleveland Indians slugger Albert Belle, with Belle’s snarling face filling the cover and near the bottom these words: Tick … Tick … Tick. The piece portrays Belle as highly intelligent and uncommonly skilled at hitting a baseball, but also as a man with anger-control issues and a history of alcohol abuse. It recalls the time he was caught using a corked bat.

“I can relate extremely well to Albert Belle,” Fred wrote, all those years ago. I’m cherry-picking the letter here. “In my judgment, Belle is a product of the culture and he regards money, status and performance as fundamental to his very being. He is what he does. He plays baseball well, makes his money and gets his status confirmed by fans and others. His behavior is largely irrelevant to his self-image and his judgment of his success.”

Two things jump out here. More, really, but I’ll cite two. The first is, you can see why our breakfasts went so long. The other is, Fred is predicting the future life and times of Tiger Woods, still an amateur golfer when that piece was published.

Here are the final two sentences: “I believe the basic driving force here is fear of failure. I believe if Albert worked at a 12-step program, his anger would subside.”

I like how, by the end, Fred is on a first-name basis with Albert Belle, as if they were sitting in a circle at one of Fred’s meetings. I can hear Fred’s high-volume voice, of course, as I read the letter. I can picture his eyes, his jowly face, his haphazard shirt-buttoning and all the rest.

The other day, flying into Philadelphia from Jacksonville, I could see Pine Valley from maybe 5,000 feet. I could definitely make out the borders of the course and almost make out the massive cross-bunker that defines the second hole. In my mind’s eye I could see, plain as day, Fred in that trap, making that bent-elbow upright backswing, advancing his ball, trudging after it, trying again.

Michael Bamberger may be reached at michael_bamberger@golf.com.