2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

Phil Mickelson’s grandfather was a Pebble Beach caddie, the first chapter of a fascinating life

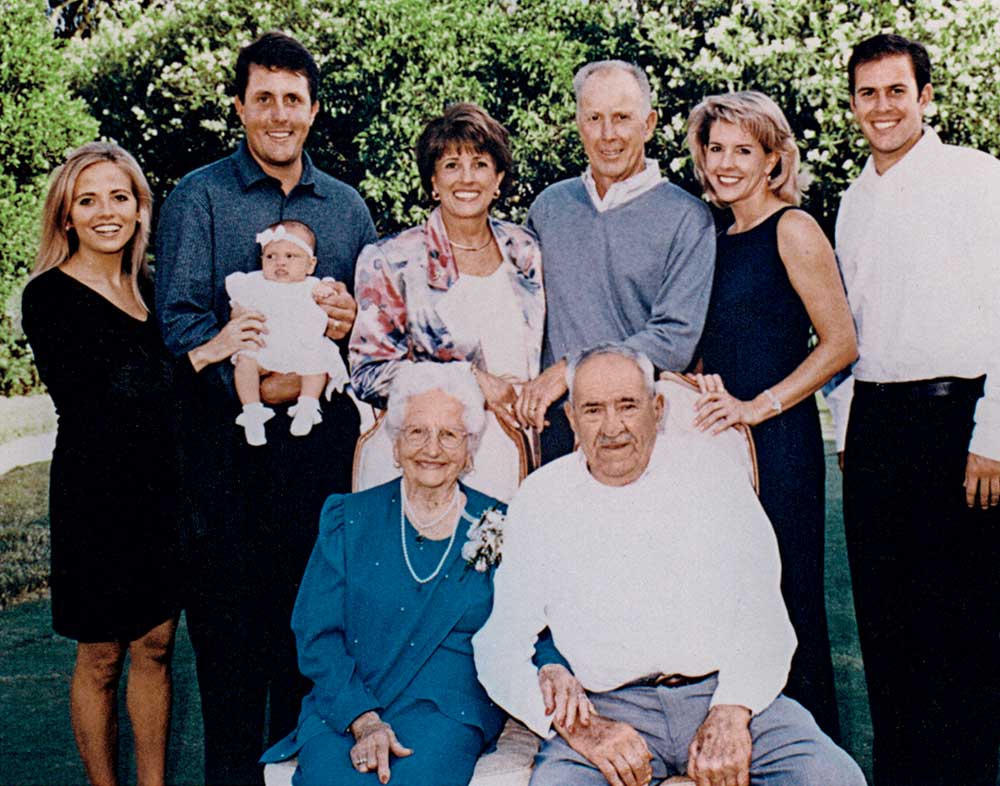

As we can all say we owe our very existence to our maternal grandfathers, Phil Mickelson can, too, and then some. You know how it is with him. Phil lives big. His mother’s father, Alfred Santos — strong, not lean, with work calluses on his fingers and boils between his knuckles — was born in 1906 in Monterey, Calif., the son of a Portuguese Cannery Row fisherman and his Portuguese wife. John Steinbeck, born in 1902, captured that briny world for eternity. Too bad he didn’t set up shop in Al’s boyhood caddie yards. He would have had a field day, the Irish kids, the Italian kids, the others, fists up at the first mention of mother. Al could hold his own.

When Pebble Beach opened for play in 1919, Al Santos was a boy caddie there, in wool pants and a newsboy cap, with cardboard insoles in his shoes. What he knew he had earned. As long as you have a silver dollar in your pocket, you’ll never be poor. Phil and his sibs, Tina and Tim, all know that one. This is what it means: Just because you have it doesn’t mean you should spend it. When Phil plays in the U.S. Open at Pebble this year, he’ll use a silver dollar as a ball marker, a coin his grandfather carried for decades, its sides worn smooth from his habitual rubbing of it.

During the Depression, right around 1930, the Santos family moved nearly 500 coastal miles south, from Monterey to San Diego. Al Santos became a “tunaman,” in the local parlance. In time he captained his own boat, the Sacramento, working with his various brothers. They were at sea for weeks at a time, long rods in hand, three poles leading to one line. It took a family to land a 150-pound tuna. Al married a local girl of Sicilian descent, Jennie Navarra, who worked in one of San Diego’s many tuna canneries. Bumble Bee, StarKist, Chicken of the Sea — all the big hooks had wharf encampments.

San Diego’s maritime prosperity helped build its public courses, and Al Santos played them, especially Balboa Park. Al and Jennie had a sleeve of girls. The first of the three, Mary, vivacious and athletic, married a Navy pilot and golf nut of Swedish descent, the original Phil Mickelson. Phil and Mary’s middle child — Philip Alfred Mickelson, born June 16, 1970 — was a golfing prodigy. One day, Christmastime 1973, the senior Phil Mickelson headed off to Balboa, to play with his father-in-law. He brought along little Phil, age three and half. Al Santos was dubious.

“This won’t last,” the grandfather said.

They worked their way to 18, a par 4 up a hill to the clubhouse. The boy had been carrying his own set of clubs, whacking one shot after the next.

He said, “Do we have to play this hole?”

“You see?” the grandfather said.

He figured the boy had reached his breaking point.

“If we play it, that means we’ll be done,” little Phil said, and that’s when Al Santos became a believer.

Every time Phil won on Tour, he’d sign a flag for his grandfather: To Champ, I’ll love you forever. Al Santos would put them up in the kitchen, with thumbtacks, until his wife (Nuna, to the grandchildren) started to complain. Too many holes.

We all can do the generational math: No Al, no Phil. No family memento silver-dollar ball marker in the pocket of his custom-made trousers. No seaside Pebble Beach walks for him, alongside his caddie brother, on the same fairways where their grandfather carried those slim canvas golf bags a century ago.

Phil, who needs the U.S. Open to complete the career grand slam, turns 49 on U.S. Open Sunday. He won at Pebble Beach earlier this year, his fifth win in the AT&T. (Nobody has won it more.) He has six second-place finishes in the U.S. Open. (Nobody has more seconds.) He’s played in three Opens at Pebble, in 1992, 2000 and 2010, and each finish was better than the last.

Can we get some air in here?!

Okay, one last intra-family note, before we return to sea level: Now and again — and this happened at Pebble in February — Phil will hand a club to Tim and say, “Did you feel Nunu there?”

* * * * *

Their Nunu is your Gramps, your Opa, your Pawpaw. But before he was Nunu, giving the grandchildren generous cash gifts at Christmas for their first cars, he was Al Santos, the third child of the 11 his mother delivered. One morning when he was in the eighth grade, and half out the door of his family’s cramped home on Church Street in Monterey, his father stopped him by way of a question.

“Where do you think you’re going?”

“To school.”

Al was the opposite of a braggart, but if you pressed him he’d tell you he was okay at school. Numbers sang to him. He had a notion about becoming an engineer.

“Your school days are over. You need to work.”

ADVERTISEMENT

So Al Santos became a caddie, starting at the Hotel Del Monte golf course in Monterey in 1917, migrating to Pebble when it opened two years later. He could make 50 cents a day, worth about $8 today, if he could go around twice.

Young Al Santos wasn’t a drinker, but he was strong-willed and sometimes rough. He spent a few nights in the local hoosegow as a young man, Mary says, not likely for anything too serious. At least, Monterey County police records don’t show any arrests for him.

He ran away at 16, hopping on and off freight trains for a half year or so, panning for gold, working in timber mills, finding odd jobs. One day, a train pulled into some station somewhere, a conductor opened a giant cargo door and sunlight chased out the boxcar’s darkness. Al Santos scurried off and various older hobos did the same but one man did not, on account of him being dead. Natural causes, as far as Mary knows.

Whether Al Santos killed a man at sea, years later, is another matter. “Pirates were shooting at his boat, trying to steal his catch, and he shot back at them,” Mary says, repeating the story as she heard it from her father. “He might have killed one of them. He didn’t want to stick around and find out.”

Mary’s a wonderful storyteller. She tells one about her father being confused by the sight of Phil as a boy wearing a football helmet inside the family’s comfortable home in a San Diego development. “He’s clumsy,” Mary explained to him. “He keeps crashing into things.” Phil inherited his mother’s gift. Al was a storyteller out of necessity. He wanted his children and grandchildren to know the circumstances from which they came. On a kitchen wall, above a door, Mary has a painting of St. Joseph cradling the baby Jesus in a simple wooden frame, guarded on one side by a giant needle, used for mending fishing nets, and the other by an old hammer. All three items came from her parents, and they hang as reminders of the role that work, faith and family has played, and still plays, in their lives.

Those are the core values that she and her husband — a trim, reserved man with Dana Carvey’s impish face — raised Tina, Phil and Tim. Phil was an altar boy as a kid. (Faith.) He lives on the range and in the gym today, though often out of public view. (Work.) He spent probably hundreds of afternoons sitting beside his grandfather. (Family.)

They often spoke about investing. Al Santos did particularly well with things he knew, with WD-40, a home-grown San Diego product; with San Diego Gas & Electric; with two San Diego mobile home parks, and with a downtown San Diego garage. While they talked, they’d have the San Diego Union-Tribune business page open in front of them and the TV turned to a cable business channel.

Al’s Roaring Twenties caddie-yard stories were never about his well-heeled charges. They were about the work. “You wanted to get there first so you could go around twice,” he’d tell Phil and the others. He never forgot what it was like to be broke, long after he became your textbook secret-millionaire-next-door. He owned one suit. When Phil and Amy bought an expensive home in ritzy Rancho Santa Fe, Al Santos came for a visit and said to Phil, “Are you sure you can afford this?”

“I can afford it,” Phil said.

The grandfather shook his hand and head and offered a Portuguese word for wonder. Meu!

Al Santos was a man of his time and place. At home he’d sit in his favorite chair while his three daughters and wife prepared supper, and say, “A glass of beer sure would be nice now.” One would immediately appear. But his admiration for his wife was obvious. More than once, as Mary remembers it, before leaving for church, Al would stop the girls at the front door and say, “Look at your mother.” Jennie Santos was not quite five feet tall, even in her church shoes. Her husband would observe her in her Sunday finery and beam.

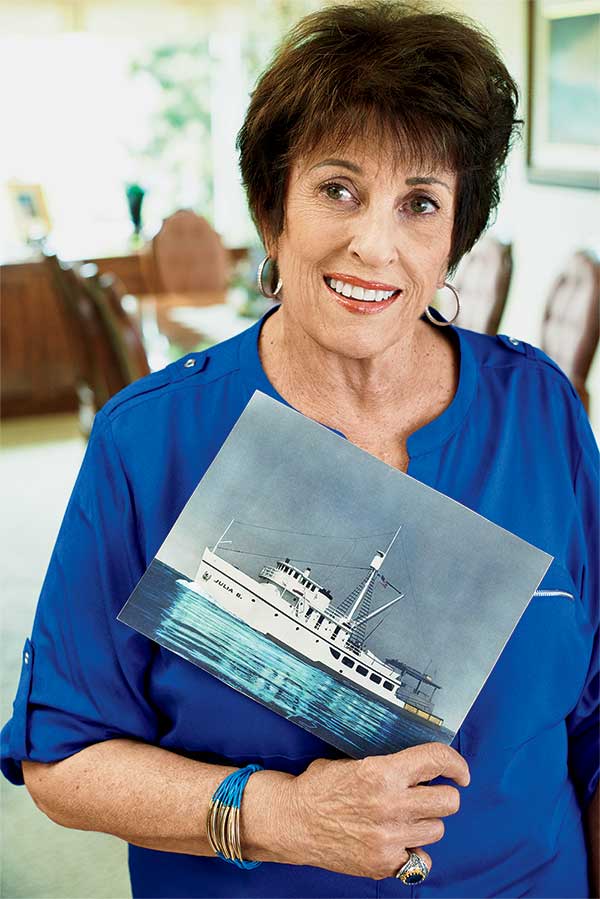

When he was out at sea — out at sea! — Al Santos had a system, ever-changing, to keep his wife informed without giving up trade secrets that other fishermen, on their radios, might intercept. Say hi to Adeline might mean that they were still chumming and trolling. Tell Mary hello might mean the boat’s fish hold was half-filled. Tell Freda we’re full meant they were heading home. That also meant 150 tons of tuna on board. Three short toots in the harbor meant the Sacramento (and later the Julia B.) was almost in.

In the 1940s, the Santos family lived in, and owned, a two-bedroom home, square and cement, a short walk from the two commercial piers that still stand today, at the bottom of Grape Street. The house does, too, on Elm Street in what today is called Little Italy but was then just the neighborhood where the fishermen lived. Later, the family moved further inland, but still inside the city limits, to a house in Mission Hills with three bedrooms. That’s what you did then, as you accrued wealth. You moved to higher ground and away from the harbor and its fishy air.

Mary, now 76, remembers that downtown Elm Street house vividly. The front door had a rectangular hatch, at eye level for an adult. Her father would knock and Mary as a little girl would stand on a stool, open the hatch and say, “Who is it?”

“It’s your pops!”

“Nobody’s home!”

It would be hard to overstate what family means to this family. When Al Santos was in his early 50s, with the family living in Mission Hills and the three girls teenagers, or close to it, he gave up the life he knew and loved, as a tunaman. The girls needed him at home, and his wife did, too. He took an assembly-line job at Convair, a division of General Dynamics, working the overnight shift. When the girls got home from school, their father was at the front door. Also when they went out on dates. The five of them had dinner together every night, at home. Along the way, Mary and a cousin developed a dish that became a family favorite, fried spaghetti with eggs, suitable for any meal.

The family also developed another tradition that Tina, Phil and Tim remember today with reverence: Grandchildren’s Day. It was typically held a few days after Christmas, and it was just for the grandchildren and Nunu and Nuna. The generation in between, the Santos sisters — Mary and Adeline and Freda — were there only to help prepare dinner. Nunu and Nuna and their seven grandchildren talked about old-times, current events, their lives. As fishing was the family business for Al and his brothers, golf became the family business for Phil and Tim and Tina, a golf instructor, so there was a lot of golf talk and fishing talk. Their grandfather’s cane could be a fishing rod in one story and a putter in another.

They remember how engaged he was. They remember his worn favorite chair, pies out of the oven, passing moments of earnestness amid the fun and games. They remember the prediction their grandfather made for Phil when they gathered in 2003. “I won’t be here for it, but you will win the Masters,” Al told Phil. The calendar turned. On Jan. 8, 2004, Al Santos died. He was 97. Three months and three days later, in the final moment of the 2004 Masters, Phil made an 18-foot birdie putt on 18, with the help of an odd rightward wiggle at the end. He won by a shot. The first of his five majors. So far.

“Nunu,” Phil said later, “nudged it in.”

ADVERTISEMENT