It’s a sun-drenched Tuesday morning, two days before the start of the Farmers Insurance Open at Torrey Pines, and Justin Rose, tall and polite English golf professional, is on the driving range of a nearby five-star resort, testing clubs and noting flight patterns. Ten people are watching, all, to varying degrees, members of Rose’s team.

His swing coach, his mental coach, his fill-in caddie. One of his chiropractors. Three executives from his new club manufacturer, Honma. A Honma club designer from Japan. A product manager. A specs guy.

Rose’s morning work is a clinic, close to perfection. In five days, he will win the old San Diego event. But this long club-test Tuesday ends at a second driving range, at Torrey Pines.

With the sun getting low, and out of the corner of his eye, Rose spots the product manager and specs guy from the morning session. They’re walking across an adjacent parking lot and away, so Rose sees only their backs. He runs after them, catches up and says:

“Thanks for all you did today.”

Is it the best grillroom story ever? No. But it has the benefit of being true, and being emblematic of the man at its center.

* * * * *

There was once a time, in the era before Justin Rose became the top-ranked golfer in the world, when a player was not complete until he had a place in the game’s oral tradition. Young Tom Morris, beloved British Open champion, dying of a “broken heart” on Christmas Day 1875, months after the death of his wife and infant child. Ben Crenshaw, his game in shambles, winning a second green coat at Augusta in 1995, days after burying his lifelong teacher, Harvey Penick, and carrying his memory, in Crenshaw’s retelling, “like a 15th club.” Ben Hogan winning the 1950 U.S. Open at Merion, 16 months after a nearly fatal car crash and without a 7-iron because, he told the scribes, “There are no 7-iron shots at Merion.” As if that could possibly be true.

And then there’s the 2013 U.S. Open, also at Merion, when our man of the hour (and maybe the man of this year’s Masters) won by two. Justin Rose closed out Father’s Day that year by playing the long par-4 18th with a sneaky-long drive followed by a for-the-ages 4-iron, two shots right out of the Hogan playbook. And ever since, whenever that Open comes up, all people want to talk about is how…Phil did this and how Phil did that and how Phil got mouthy with Mike Davis on that first par 3 and how Phil missed the green on that dollhouse par 3 with a wedge in his hands.

Makes you want to holler:

HOW ’BOUT ROSE?

His play on that Sunday was airtight when there was no air in the room, and it’s been pretty much the same ever since. So where’s his what-becomes-a-legend moment?

But here’s the good news, for Justin Rose and his wife (Kate) and their son and daughter (Leo and Lottie) and various Rose descendants as yet unborn: It doesn’t matter.

That’s because Justin Rose is the prototypical modern golfer. Yes, he’s 38 in a game that’s trending young. But he’s not worried about whether he has more future than past. He’s not worried about his place in the game’s lore. He’s not worried that no great grillroom stories cling to him.

That’s because he’s in the building business. His specialty, the thing to which he’s devoted, is the construction of 72-hole scores. As Warren Buffett said once after investing in a cement company, “Try to contain your excitement.”

You can almost count on Rose to post a good 72-hole score no matter where in the world he and Club Rose have landed. (Kate Rose, in a manner of speaking, is the club’s manager.) On any given week, the course can be easy or hard or in between. The weather can be good or bad or in between. The competition can be stout or gentle or in between. Whatever it is, Rose is going to make repeating, well-considered swings that will produce square strikes with all 14 clubs, and it doesn’t matter whether you like or don’t like his yellow sunglasses or his tai chi practice swing or his green-reading out of a book.

There’s a record of nearly every practice shot Rose hits, and by the time he’s on the course, there is almost no guesswork. Even Bryson DeChambeau doesn’t have, as Rose does, a performance/mental coach (Jason Goldsmith) who walks among paying spectators, stopwatch in hand, timing the golfer’s pre-shot routine on nearly every swing. Their work with FocusBand—a brainwave-reading headband that trains golfers to get in a heightened no-distraction state called “mushin”—is done in more private settings.

Yes, mushin is a cousin to be the ball. Mock it at your own risk. Twelve or so years from now, Rose will be winking at you from the World Golf Hall of Fame.

If Rose wins at Augusta this year—and who among us would be surprised if he did?—his victory may not leave you tingling all through 60 Minutes. A Rose win would come out of the Nick Faldo slide-rule tradition, not the Peter Alliss here’s-a-story one. (Alliss is a BBC legend.) Calling the shots for CBS, Sir Nick, winner of three green coats, will be looking in a mirror. Golf for Rose—as it was for Faldo and Mac O’Grady and Homer Kelley of The Golfing Machine—is, first and foremost, an engineering problem. That is today’s game, and by tomorrow it will be truer yet. Just ask any kid playing Division I college golf about shaft weight, launch angle, spin rate and ball speed. Your answers will be in grams and degrees, in revolutions per minute and miles per hour. Rose is hyper-fluent in all of that.

He wasn’t always this way. At 18, Rose was playing professional golf, and missing his first 21 cuts in Europe. He was a feel player and a savant. Science came later. But the thing about 1998 is that he did not quit, and that made all the difference—for Rose, for Club Rose, for many others. The Kate & Justin Rose Foundation has provided thousands of healthy meals, educational books and one-of-a-kind daytrips to needy kids.

There is always the road not taken. Had Rose not pursued professional golf, he’ll tell you, he would have become an architect. And in a manner of speaking, he is.

“The Golden Gate Bridge began as an engineering problem,” says Sean Foley, Rose’s swing coach for the past decade. That is, how are motorists going to travel across the mile of ocean water that separates Marin County and San Francisco? “It ended up as an artwork.” Their process is to try new things, keep them if they work, discard them if they don’t.

Foley and Rose match up well. Foley worked for Tiger Woods in a difficult four-year period, and it would be hard to say how much impact he really had on him. He helped turn Stephen Ames, Sean O’Hair and Hunter Mahan into formidable Tour players. He has worked with 23-year-old Cameron Champ for the past eight years. But by far his most significant relationship has been with Justin Rose. They have more than 4,000 days together, or parts of them.

That’s because Rose-Foley has produced a paradigm that is already impacting the generation of elite golfers coming up, planted on the range with orange TrackMans behind them, standing guard. Seve Ballesteros on a remote Spanish beach as a dreaming boy, swinging at rocks with a rusty 3-iron—it’s a beautiful image, right? It belongs in a museum.

“I’ll take science over intuition every time,” Foley says. That’s why there are so many numbers in their conversations, so much discussion of biomechanics. Foley sees Rose as a different creature than most players, more interested in mastery than trophies, while practicing as if he hasn’t accomplished a thing. “I promise you I’ve learned more from Rosie than he has from me.”

Rose would never agree with that statement. For one thing, it would be immodest of him, and Rose doesn’t do immodest. More to the point, the problem with Foley’s I’ve-learned-more claim is that it can’t be measured. Rose’s stock-in-trade is that which can.

This is not to suggest Justin Rose is a golfing cyborg in Bonobos clothing. For one thing, he has a nice sense of humor. At that morning San Diego range session, Foley was prattling on about shot dispersion and launch angles and other Cape Canaveral stuff. Somebody asked Rose, “What percentage of that do you actually understand?”

Not the right question.

“I understand all of it,” he said. “But how much of it do I pay attention to? That’s the question.”

Rose will admit to his team (but not to you) that he’s still getting over his runner-up finish to Sergio Garcia at the 2017 Masters. “It hurt, it hurts,” says Rose’s longtime caddie, Mark (Fooch) Fulcher, a big-boned Englishman with a big personality. Garcia played spectacular golf down the stretch, along with spectacularly lucky golf, and he won on the first hole of a sudden-death playoff, making a birdie to Rose’s bogey. “The winner always gets lucky,” Rose said. “I had luck when I won at Merion.”

What Rose and his people don’t do is brood about that Sunday (or any other day). They make mistakes, as we all do. They learn from them, as some of us do. As the saying goes, It’s a process. “I thought I hit a perfect putt,” Rose says of the seven-footer for birdie he missed on the 72nd hole. The specific lesson there is this: That putts breaks less than it looks. Noted, literally.

Rose plays all his competitive rounds, at Augusta and elsewhere, in his head, on the range and out of his yardage book, before they are played for real. His practice round is the actor’s dress rehearsal. Did Seve do it that way? No. But that round-in-the-mind thing is Tiger 101.

* * * * *

The Rose family lives in Albany, The Bahamas, where there is no income tax. (More Buffett: Wealth is not what you make but what you keep. His housekeeper comes twice a month.) There’s every reason to think this Justin Rose is rich. His feeling is he’s worked too hard to get it to waste it. Asked about the racehorses he and Kate own, Rose says, “Race horse.” (Master Merion: 15 starts, four wins. Nice win rate!) Rose plays and practices on the resort course in Albany where Woods holds his annual 18-player December event, the Hero World Challenge, and where Woods goes on getaway vacations. An amazing and occasional sight for members there is to see Woods watch Rose practice.

There’s not a player in the world today who could go on a run anything like Tiger’s in the early 2000s. There’s too much parity, too much information, too much money, too much good equipment. But there’s no player better equipped than Rose to contend in four or five of the next, say, 12 majors and maybe win (this is outrageous!) two of them. That’s because Rose is strong through the bag, through the body and through the head. His off-course life is clear and his on-course life is, too. He shows up ready. He doesn’t traffic in drama, gossip, passing controversies, Tour politics, Twitter quotes making the rounds. His eye is on the prize.

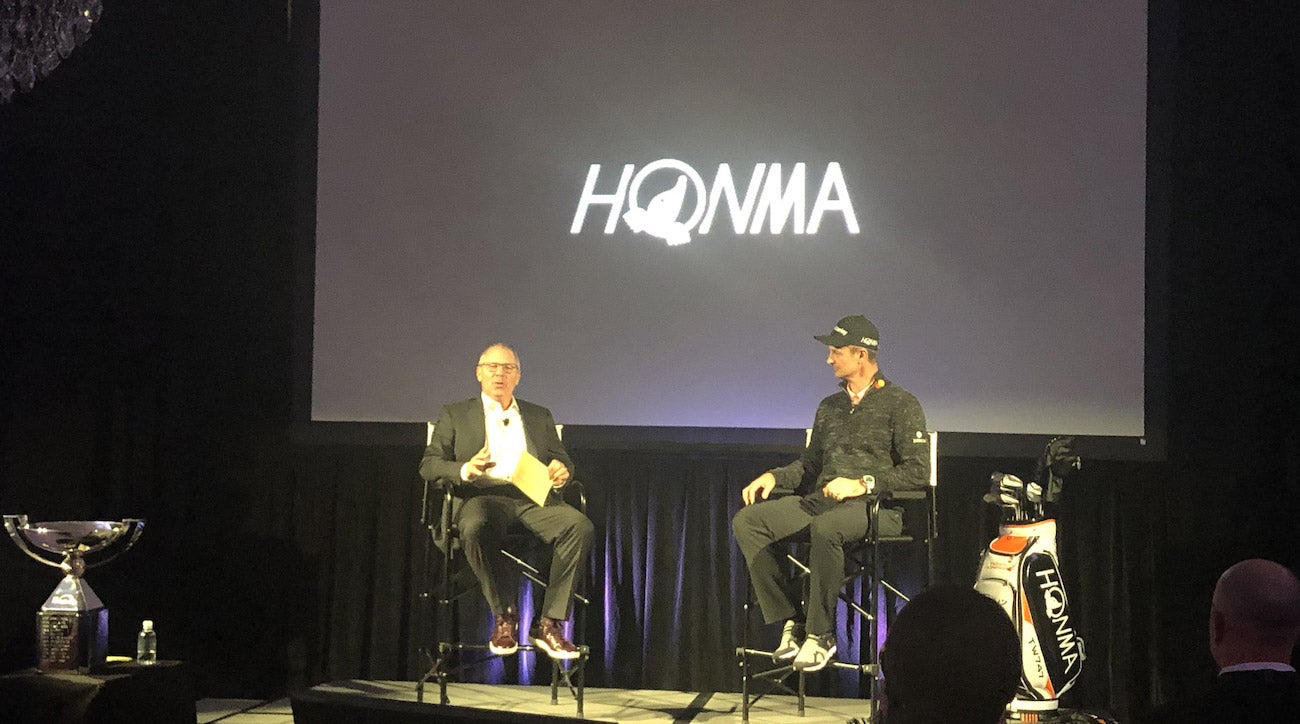

Since Rose’s U.S. Open win in 2013, there’s not a pro in the world with a playing CV quite like his. He won on the European Tour and the PGA Tour in 2014. He won in Hong Kong and New Orleans in 2015. He won an Olympic gold medal in Brazil in 2016. He won in China in 2017. He won the $10 million FedEx payout at East Lake in Atlanta last September. One week later, he was on the winning Ryder Cup team in Paris. In November, he won in Turkey. He spent December with Leo on the touchline of a football pitch and with Lottie on the fence of a riding ring. In mid-January he put 11 new made-in-Japan clubs in his bag. In late January he won at Torrey Pines with his new Honma clubs in his new Honma bag, on which some of the lettering is in Japanese. Asked about that new bag, Rory McIlroy (being funny) said, “I see his name’s not written in English—that would freak me out a bit.”

Rose counts McIlroy and Garcia and other European Ryder Cup players as friends, but on the Phil-Tiger spectrum for gregariousness, Rose leans in the Woods fly-solo direction. “I might have more mates among the caddies,” Rose will tell you. That’s common, among the European players, a way for some of them to hold on to their working-class roots. Hardscrabble boyhoods are often the springboard to their success in the first place. You could say that of Ian Poulter, Darren Clarke, McIlroy and others, Rose among them. He speaks of a benefactor, a local businessman named Dave Cross, at Rose’s home club in England who helped finance his amateur career and early pro career when family money was beyond tight. Rose’s parents owned, and struggled with, a shop that sold dancewear and swimwear. Ken Rose, who introduced Justin to golf, died of cancer in 2002 at age 57. When Rose won at Merion, the first place he looked was straight up.

Rose’s closest friend in professional golf is Henrik Stenson. Rose won at Torrey with Stenson’s former caddie, Gareth Lord, an Englishman, working for him. Fulcher was in his adopted home in South Florida, recuperating from mitral valve repair heart surgery. Kate Rose was at the hospital for the surgery. Fulcher expects to be back in action before the Masters.

In victory at Torrey Pines, Justin Rose looked into the CBS camera, cited his caddie by nickname and said, “That was for you, mate. We love you.”

Yes, there it was, on live TV, the L-word, from a professional golfer who was speaking not of his wife or children or sponsor, but his caddie. In this case, the bearded, pencil-chewing, track-loving Mark (Fooch) Fulcher.

So, no—Justin Rose is not a golfing cyborg. Nor is he a golfing machine. He made two doubles while leading in the third round at Torrey. He made five 5s on the front nine in the fourth round. And still he managed to shoot 21 under par and win by two. That tells you that he’s excellent at golf, and some other useful things, like remaining composed.

He got it done, said nice things, packed it up and off he went. Justin Rose, tall, polite English golf professional.

Maybe you’re wondering: Will he ever become part of the game’s lore?

That question is so yesterday.

Here’s a better one.

Does it matter?