Rickie Fowler’s walk through time and back into contention at the Players

Rickie Fowler’s walk through time and back into contention at the Players

That Maryland high school golfer who DQ’d himself? There’s much more to the story

David Regala, a slight 5-foot-5-inch freshman at Severna Park (Md.) High School, knew there was a problem when he saw a 76 next to his name.

Regala, who goes by “D.A.,” had, in fact, shot a 78 on the second and final day of the Maryland state high school golf championship earlier this year but had mistakenly signed for two strokes better than that. As scoring transgressions go, it was hardly scandalous. Instead of a four-way tie for 28th, Regala‚Äôs correct two-day score dropped him into a tie for 32nd.

More significant was that when Regala’s score appeared on the leaderboard by the 18th green at the University of Maryland Golf Course, only he knew of the improper accounting. With his scorecard already submitted, the 14-year-old could have walked away scot-free. Instead, he turned himself in, well aware of the harsh consequence: disqualification.

It was a strange day for Regala, and not just because of the DQ. He had started his round on the 14th hole. Seven holes in, on the par-4 2nd, the walking scorer in Regala‚Äôs group incorrectly recorded a 5 on Regala‚Äôs card. After consulting with Regala and others in the group, the scorer realized his error and changed Regala‚Äôs score to a 4. On the very next hole, a similar discussion ensued ‚ÄĒ¬†5 or 4? Again, everyone agreed that Regala had made a 4.

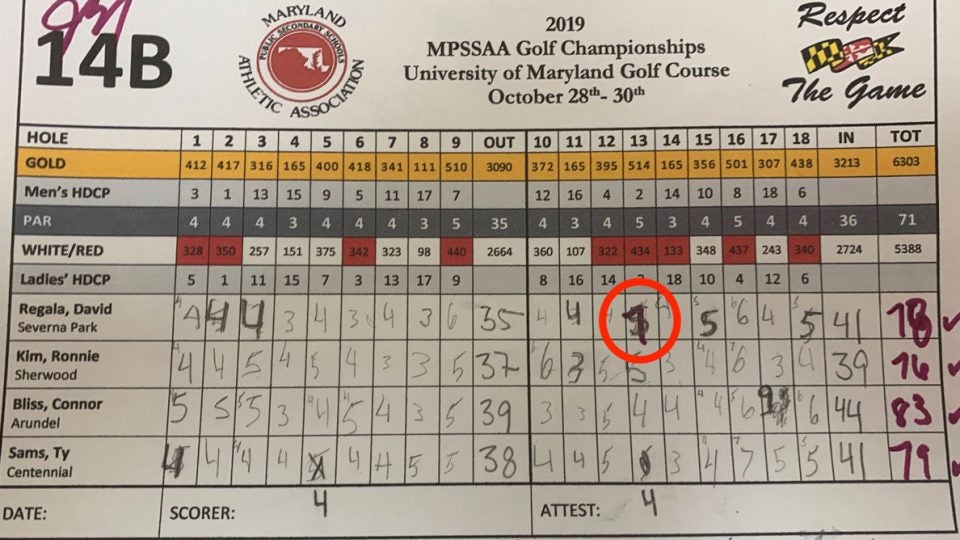

After his round, Regala hastily signed his card, unaware that he was endorsing an incorrect score, although not on the 2nd or 3rd hole. On No. 13, his last hole of the round, Regala had made a 7 but penciled in a 5. The honest, if careless, goof had gone unnoticed by Regala, the scorer on the course, an official from the Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association and the three other players in his foursome.

“I was barely paying attention when we sat down with the tournament rep,‚ÄĚ Regala told GOLF.com in a recent phone interview. “When he asked if we had confirmed our scores, I thought he was referencing the discussion about Nos. 2 and 3, so I signed the card.‚ÄĚ

It was only after his score had been posted on the leaderboard that Regala realized his mistake. As Regala walked back into the clubhouse to alert tournament officials, Regala’s father reminded his son of the penalty awaiting him, not to dissuade him from confessing but to prepare him for the outcome.

“The rules are the rules,‚ÄĚ the boy said, without breaking stride. “I didn‚Äôt shoot a 76.‚ÄĚ

Regala reported the mistake to Phelps Prescott, the tournament director for the Maryland Public Secondary Schools Athletic Association. “The first thing I did was thank him for being honest, and then I told him he had done the right thing,‚ÄĚ Prescott said.

The hard part came next.

“I‚Äôm sorry,‚ÄĚ Prescott said, “but you‚Äôre disqualified.”

Scoring mistakes happen all the time, but this incident caught my eye because it happened in Anne Arundel County, the same county where a widespread high school golf cheating scandal came to light in 2012. I know this because I broke the story while covering that year’s county golf championship for Annapolis’ daily newspaper, the Capital Gazette.

I first got wind of the issue when Jake Manley, a senior from Broadneck High School, finished up his round. As Manley walked off the 18th green, I overheard Manley tell Prescott, the tournament director, that he believed his competitors had been stroke-shaving during the regular season, or signing for lower scores than they had actually made.

My ears perked up. Later that day I reviewed the county’s season-long scoring averages and saw that Manley seemingly was on to something: 26 percent of the county championship field (19 of 74 players) had signed for scores 10 strokes higher than their Average Over Par for the season. At a regional qualifier the following week, county officials, realizing they couldn’t rely on regular season AOP to seed the field, instead estimated players’ scoring averages. That plan also failed when 31 percent of entrants (20 of 64) exceeded the 10-stroke barrier.

On both days, several players were 20 strokes or more beyond their AOP.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Capital Gazette’s readership includes teachers, coaches and administrators, as well as state and federal politicians. When the paper ran my story about the stroke-shaving epidemic, stakeholders began contacting Prescott directly.

“That Sunday, I probably took 15-20 calls from administrators and coaches, and on Monday, I received twice as many emails,‚ÄĚ Prescott told me the other day. “There was a lot of reaction, ranging from ‚ÄėMy kid would never do it‚Äô to ‚ÄėOh yeah, we have a big problem.‚Äô It was obvious we couldn‚Äôt brush this aside as a few rogue players.”

Prescott, a former NCAA baseball umpire who teaches history at Arundel High School, knew he needed to act, and swiftly. He teamed with Pete Hiskey, Manley’s high school golf coach, to create a roadmap to curb the cheating.

The first call went to Mike Cumberpatch, the executive director of the Middle Atlantic and Washington Metropolitan Golf Associations, who volunteered to teach a rules class before the start of the 2013 season. Later, Bill Sporre, a retired but highly respected PGA professional, came aboard to help school the young players. What started as a 20-minute speaking engagement is now a mandatory, five-station workshop hosted by the United States Naval Academy golf course. Topics include everything from bunker and putting green etiquette to how to handle drops and loose impediments.

Stroke-shaving is also confronted head-on, in a session dedicated to the responsibilities of keeping a scorecard, specifically the importance of counting strokes honestly. Coaches and players are also advised on the importance of ethics.

This piece is crucial, because bullying played a role in the 2012 scandal. In extreme cases, upperclassmen were intimidating players three and four years their younger into keeping quiet about illicit scoring practices.

“The biggest problem with cheating is it has to be addressed if and when it happens, and sometimes we expect players who are 12, 13 or 14 years old to be whistleblowers,‚ÄĚ Prescott said. “As adults, we have to do a better job teaching the ethics of the game.‚ÄĚ

Tournament directors, governing boards and state high school associations still grapple with the issues like the ones Prescott faced in 2012.

One of the most egregious examples occurred just last year at Michigan‚Äôs high school state tournament. When two schools, Anchor Bay and L‚ÄôAnse Creuse, were paired together at a regional qualifier, their reported scores ‚ÄĒ in the high 60s and low 70s ‚ÄĒ¬†were far lower than their season averages. Howls of foul play followed. Rochester Adams and Bloomfield Hills, two schools excluded from the state tournament, filed a hastily prepared appeal that proved fruitless. The Michigan High School Athletic Association declared the scores would stand, because they couldn‚Äôt prove the allegations of cheating or collusion.

The next week, L’Anse Creuse and Anchor Bay finished last and next-to-last at the state championship, respectively, with some of their scores creeping into the mid-90s.

Solutions at the high school level are not easy to administer. There are no uniformed rules officials pacing the fairways, or meet and match officials like you’d find in, say, swimming or tennis. Players must police themselves.

Cody Inglis, assistant director of the Michigan High School Athletic Association, told GOLF.com that his state’s scandal led to a re-evaluation of several protocols. In 2019, every player in a foursome was tasked with scoring for another player; players also must announce their scores as soon as a putt drops. The association now dispatches a rules official to every regional event, and coaches are permitted to coach on the course.

Previously outlawed, phones are now permitted in tournament play. Players can use their devices to contact a rules official for rules queries, or a coach or tournament administrator should they encounter a health or safety issue. Players also may use distance-measuring and scoring apps.

“It‚Äôs a constant effort to stay on top of this kind of problem,‚ÄĚ said Inglis, adding that the increased engagement from coaches and administrators, and through apps, means more eyeballs on the players. “Teaching honor and integrity is paramount to everything we do in Michigan.‚ÄĚ

That mantra also seems to be sticking back in Anne Arundel County, where stroke-shaving in the top high school ranks appears to have been squashed. As for D.A. Regala, he has become a bit of a rock star, his disqualification representing a shining example of how much times have changed in his county.

“Word spread so fast, I never thought it would turn into a national story,‚ÄĚ Regala said. “I was just doing what‚Äôs expected of me. I could have walked away and no one would have known, but I would have known.‚ÄĚ

T.C. Cameron is the author of Miracle Maples and Navy Football: Return to Glory. He has lived in Annapolis, Md., since 2009.

ADVERTISEMENT