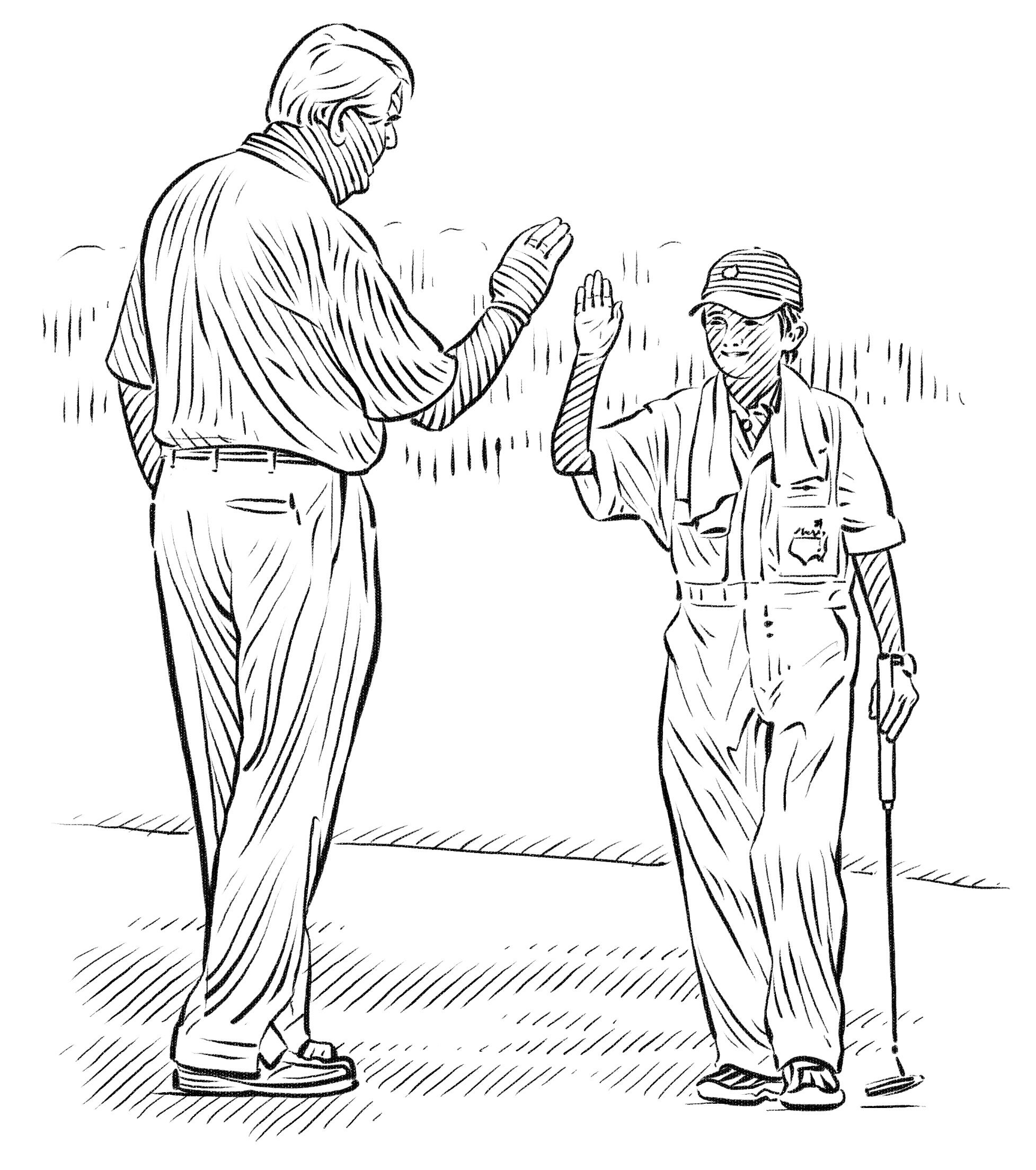

We see and we don’t. There was old Charlie Coody, last year at Augusta, playing in the casual Wednesday Par-3 tournament. Coody had two kids caddying for him, skinny brothers in borrowed white jumpsuits, confidently taking over putting duties from the 1971 Masters champ on the little course’s flying-saucer greens. Their father, fit and trim, watched on his toes in his green club coat. Beside him was his beautiful wife. The man’s father, stout and white-haired, a member himself, took it all in too. Three generations, gathered under the pines. The still pond, the manicured grass, all that April promise. A picture.

You couldn’t know that the handsome couple, Turner and Tara Simkins, were jumpier than cats at midnight. Would Brennan, the older and smaller of the two caddying brothers, make it through the nine holes? A question that falls down laughing when you stand it against this one: Would he make it at all?

Brennan had already been to the funerals of five friends he had made in the oncology department at St. Jude Children’s in Memphis: Cassidy, Cameron, Carlton, Carissa and Patrick. In January 2009, on his seventh birthday, Brennan had been diagnosed with a rare form of leukemia. He had a 50 percent chance of a full recovery, his doctors said, if his chemo and the bone-marrow transplant were successful. The next 18 months of his life, to grossly oversimplify it, went like this: chemotherapy, bone-marrow transplant, hope, relapse; chemo, transplant, hope, relapse; chemo, transplant, hope, relapse. The doctors prepared the family for round four, and they lowered expectations. Brennan’s chances of survival were now one quarter of one percent, they said.

MORE MASTERS: Visit GOLF.com’s Masters Hub

There was no known case of a child making it through four rounds of this particular hell. No wonder Brennan could read a green, a thousand spectators watching, with the nonchalance of a kid reading the back of a Lucky Charms box.

The parents’ edginess that day had come out of Brennan’s most recent medical report, with a red-flag indicator that his fourth bone-marrow transplant was not holding up. They feared relapse was on the horizon. Turner had recently finished writing a book, Possibilities, a moving account of his family’s ordeal and faith, both scientific and religious. The book was out, but in another sense the final chapter had not yet been written. The specter of death had invaded the family like a low-grade fever.

In 2012, Brennan spent a day with Robin Williams, who had donated a day to St. Jude’s. Brennan fell for the actor. Two years later, it was up to his mother to tell Brennan about the suicide of the big-hearted genius. Later, the Don McLean song “Vincent” came on the car radio. This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you. “I think this song is about Robin,” the boy told his mother.

Brennan knows the song because his father is a devoted music buff. Turner Simkins is a guitarist, writer, hunter, wine drinker, lapsed Presbyterian, meditating Catholic, and a New Urbanism developer. (Look it up.) He’s Old South and half New Agey, and he once made a 1 on No. 4 at Augusta National. He’s about as white as his father’s hair, and he already has a title for his next book, as yet unwritten, about his many black relatives: Cousins in the Closet. Tara and Turner and their three sons live across the Savannah River from downtown Augusta and in a state of perpetual funk. Worn Orientals, friends-and-family art, sleeping dog in the kitchen.

Turner’s office is across the street, through a hair salon, up a flight of stairs. He drinks tap water out of Augusta National plastic cups that once held cold clubhouse beers. On page 8 of Possibilities, Turner tells about getting the news of Brennan’s diagnosis and wondering what it would mean for Brennan’s future in golf. “Of all things,” he writes with admirable candor.

Brennan got through the nine holes with Charlie Coody. The fourth bone-marrow transplant held up. In January, he turned 14 and returned to St. Jude’s for a battery of tests. Five years, cancer-free! The doctors proclaimed Brennan cured and a medical miracle.

Brennan has been compromised by his harsh and various treatments. He’s tiny, polite, smart, athletic, calm, tired, alive. He’ll likely be back with Coody at the Par-3 this year.

On a school-day afternoon a few weeks ago, the Simkins boys—a band of yes-sir brothers and their English-major father—were having a putting war on the massive, sloping practice green at the Augusta Country Club, right next door to the National. Tara, a native Augustan, stood in the fading light and cool wind and watched. Time cannot go too slowly for this family, and for a moment that afternoon it came nearly to a stop. Tara thought, That’s a foursome.