The GreenFlea Market opened in 1982 as a yard sale for parents to raise money for their kids’ schools. Nearly 40 years later, it’s still there, every Sunday, rain or shine, on the corner of West 76th Street and Columbus Avenue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. In 2016, its name changed to Grand Bazaar NYC, and today, with more than 200 venders, it’s the largest weekly curated market in New York City.

It’s got everything. Vintage books and blues records, fur coats and jean jackets, paintings and posters, wood chairs and varnished tables, even wild-boar tusks dangling from shimmering necklaces. There’s junk, too — of course, junk is in the eye of the beholder.

Browsing the bazaar has been a Sunday ritual for me since I moved into the neighborhood, although I rarely buy anything more than a gyro. On a recent morning, I weaved in and out of the aisles until I came upon one of the final pop-up tents. The man behind the table was named Larry. He had a mustache, and he wore a black cowboy hat and had an untucked striped shirt hanging past his blue jeans. Larry always has the best spread because he never sells just one thing — he has lots of everything, piled high and laughably organized. If you’re brave, you’ll dig. On this occasion, leaning against one of the tables and wrapped in a bungee cord, were nine golf clubs — eight rusty putters and a Callaway eight-iron. Larry was talking to someone when he saw me pick up the clubs and examine them. “Ten bucks for all of ’em,” he said, adding that he’d procured them somewhere in Connecticut. “They ain’t stolen or nothing.”

I had no plans for the clubs, but it was a deal too good to resist. I figured I’d end up bringing them into the office, where clubs new and old are scattered about like toys in a playroom.

When I arrived home, I laid the putters across the floor and began inspecting them. Two immediately became my favorites: a vintage Robot (the same model President John F. Kennedy had used) and an Acushnet Bulls Eye. The latter had a faded piece of tape wrapped around the shaft. The text on the top of the tape read “SHAKER HEIGHTS C.C.” And below that: “SHAKER HEIGHTS, OHIO.” Sandwiched between, written in ink in all caps, it said: “M.J. BERNET.”

My search for the putter’s owner had begun.

* * * * * *

I don’t know why I was drawn to this golf club, or why I felt the need to find its owner. There’s something alluring and majestic about used clubs, especially putters; they’re delicate and handled with care. More than any other club, a trusty putter is like a beloved family member, falling somewhere between your dog and first born. Putters hold sentimental value that other clubs don’t. Maybe that’s what piqued my interest. Or maybe the club reminded me of my grandpa and his old baseball glove, still missing after all these years. I wanted that glove — and still want that glove, stained with gold paint from celebrating his 500th career high school coaching win — but it was accidentally given away when my grandparents moved out of their house several years ago. That piece of leather would mean a lot to me; maybe this putter would mean the same to somebody else.

I spent the next two days furiously searching the web for anything I could find about Shaker Heights C.C. and M.J. Bernet. I also emailed the folks at Titleist with questions about the putter, and the Shaker Heights communications team to ask about membership records. The next day I heard back from Amanda Eckertson, the club’s director of membership and marketing and a self-described history nerd. Eckertson explained that the club, home to an early Donald Ross design, opened in 1913 and helped shape the surrounding communities. She said she’d look into the Bernets’ file — if there was one — and get back to me.

Through my own search I found out the Bernets were an affluent family in the Cleveland suburbs, stemming from patriarch John Joseph Bernet, who rose to prominence in the early 1900s when the railroad was king. John Joseph was hired by the Van Sweringen brothers to manage their coast-to-coast railroad empire and was later dubbed the “Doctor of Sick Railroads.” He helped found John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio, and its first dorm, Bernet Hall, still bears his name.

Presumably the putter had belonged to John Joseph’s kin, but who exactly? I devoured biographies about John Joseph and clicked through some ancestry sites that offered incomplete family trees. I learned John Joseph married Helen Woods and had four kids; the youngest, Maurice Joseph Bernet, was born in Buffalo, N.Y., on Jan. 11, 1903.

Maurice Joseph — M.J.! Surely this was my guy. Believing I had my answer, I dug deeper into M.J.’s history. I scoured online obituaries for Bernets and eventually found contact information for a distant relative, Diane Bernet, a small business owner in Florida. I reached out via email, and she called me that day.

She told me her father was James, who was the son of M.J. Bernet. She didn’t know M.J. well. He was her step-grandfather and died when she was young, but she was well aware of the family’s prominent railroad past. (M.J., following in his father’s footsteps, was the president and owner of the International Supply Co. and the Terminal Supply Co.) Diane told me to call her son, Lake, who knew more about the family’s history and who still lives on the same property that M.J. grew up on in Harborcreek, Pa., the fourth generation to do so.

It took me a week to track down Lake. He lives with Diane’s 89-year-old mother, Virginia, both of whom have fond memories of M.J., noting that he and his wife were “upper crust but not flashy” and that M.J. was friendly with Liberace. At the end of our chat, I felt satisfied, having learned the backstory of my putter’s owner. Mission accomplished. Until … it wasn’t.

The next day an email arrived in my inbox. It was Amanda again, from Shaker Heights C.C.

“Let’s just say the Bernets have a neat story,” Amanda wrote, teasing a follow-up email to come. She later sent me a note that included nine attachments and three hyperlinks, most of which led to information I hadn’t uncovered yet. Among the trove were old Bernet club acceptance letters, board resignations, requests for a leave of absence during the war, a pair of obituaries and more. It’s believed that the Bernets, beginning with John Joseph, were members of Shaker Heights when the club opened over a century ago.

Also, I had one important detail wrong.

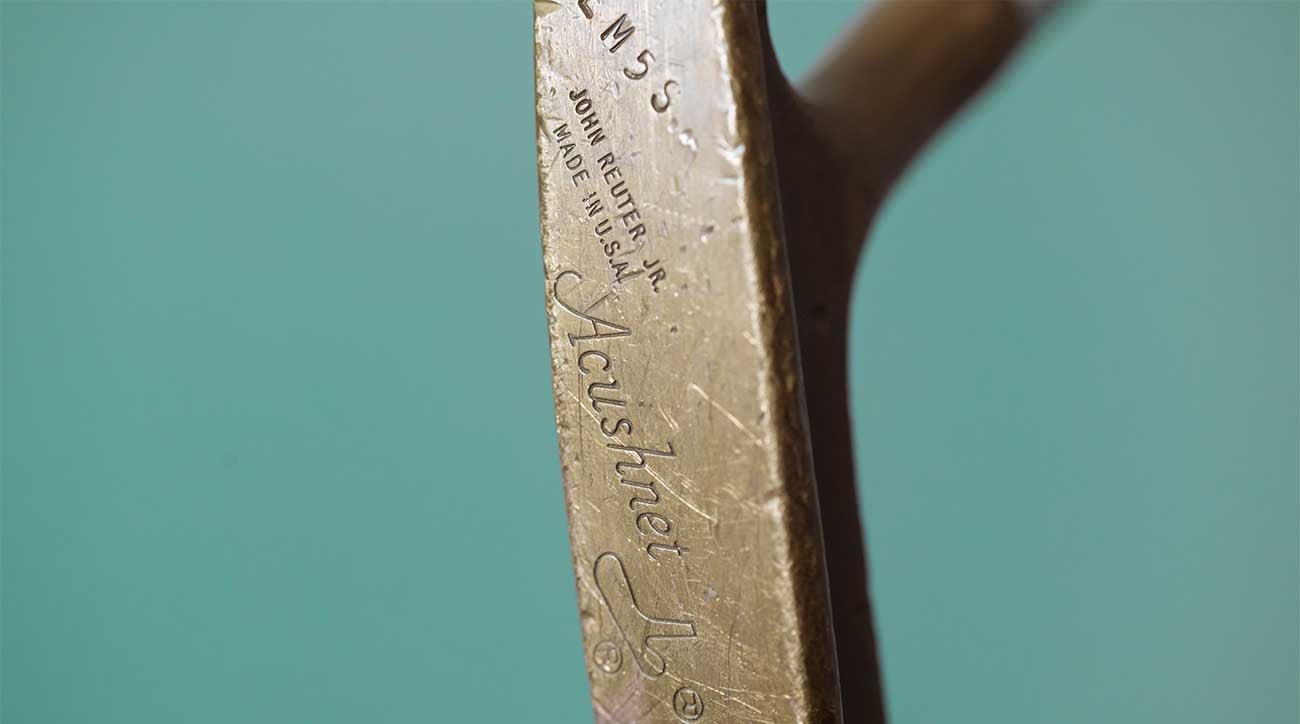

M.J. Bernet had four kids, but one of them, M.J. Bernet Jr., was omitted from the ancestry sites I had perused. The next day I heard back from a Titleist representative, who said the “FL M 5 S” on the head of the putter stands for flange (FL), medium lie (M), 35-inch length (5) and standard grip (S). He added that since the putter is a John Reuter Jr. Acushnet model, it must have been produced after 1962, the year Acushnet acquired the Reuter company and just five years before M.J. Bernet Sr. died. He and the putter seemed like an unlikely match. The son, though, was born in 1932. Like his father, M.J. Jr. was an avid golfer and Shaker Heights member. The putter was much more likely to have been his.

One problem: this M.J. Bernet, who went by Morrie, was also dead. Thanks to Amanda, I learned he, too, had four kids, the oldest being — you guessed it — M.J. Bernet III, who goes by Mitch. After yet more Googling, I tracked down an email address for Mitch. A couple of days later we connected by phone.

“It was definitely my dad’s,” said Mitch, who is 61. Mitch said his father bought all his clubs from Shaker Heights pro Don Perne, and Shaker Heights always labeled clubs with the owner’s name near the shaft to help the caddies. “He always putted with that,” Mitch said. “I tried to get him into the new world when those Ping Ansers came out and all the pros were playing with them. I bought him one [for his 50th birthday]. He putted with that for a couple of years but was always mad he gave up [the Bulls Eye].”

After searching the internet for weeks, scrolling through online library archives, rummaging over obituaries and awkwardly cold calling a handful of family members with Bernet ties, I had finally found the putter’s owner.

And so much more.

ADVERTISEMENT

* * * * * *

Morrie, the owner of my flea-market putter, grew up outside of Erie, Pa., and later enrolled at John Carroll University, where as an offensive lineman he blocked for future NFL Hall of Famer Don Shula. After graduation he entered the railroad business, and in 1955 he and a friend hopped on a train for what was supposed to be a quick trip to New York City. The plan was to meet up with two coeds at Marymount College on East 71st Street in Manhattan, but on their way there Morrie’s friend had to return to Cleveland when his mother fell ill.

Morrie continued, and at his friend’s request took the girls out to dinner anyway. Morrie and the girls had never met before, save for a few phone calls, but Morrie quickly hit it off with the girl his buddy was supposed to meet. They went out together for the next seven nights, and before Morrie left New York he proposed to Helen Jane O’Reilly. The couple got married the next year and settled down in Chagrin Falls, Ohio, before moving to nearby Shaker Heights. The first of their four children, M.J. Bernet III, was born in 1958. “Mitch” was followed by Lisa (now age 60), John (58) and Jim (55).

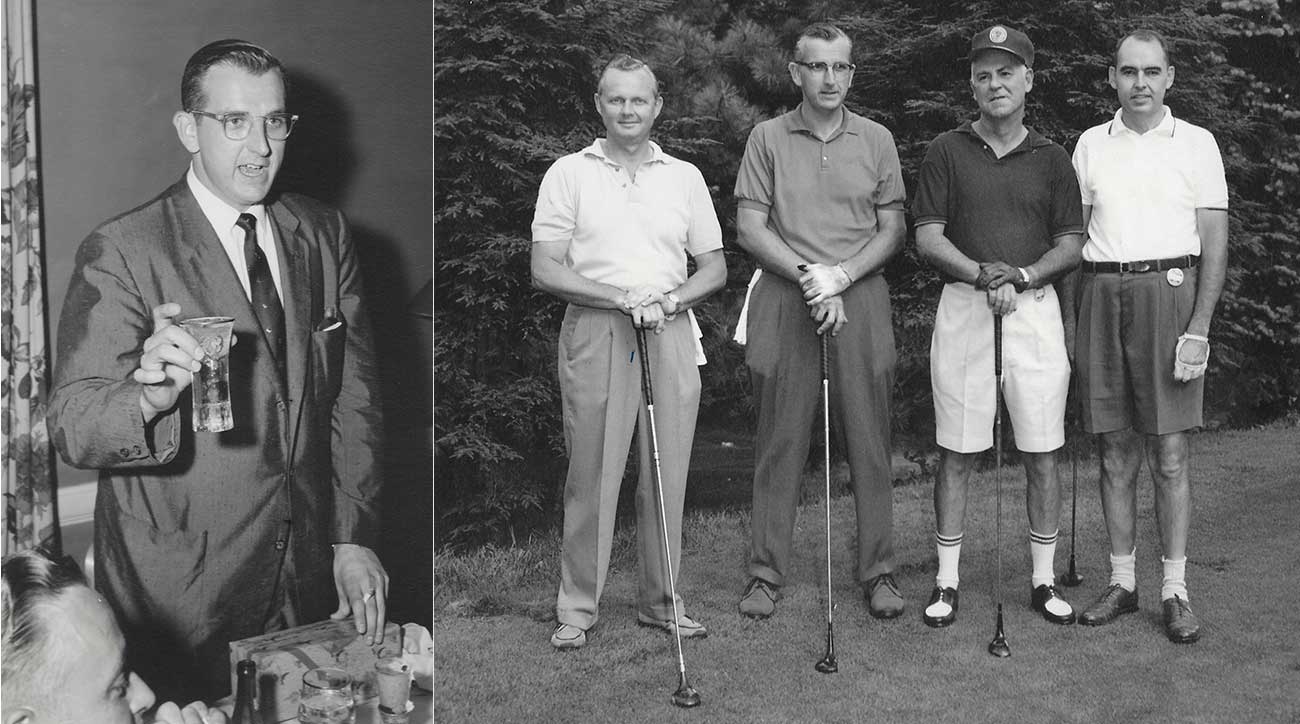

Morrie’s father was a stud golfer who won club championships at Shaker Heights in 1924 and ’28, but Morrie didn’t pick up the game until later in life. When the bug bit, though, it bit hard. Morrie practiced endlessly, and just like his father, he became a scratch player within a couple of years. Morrie passed on his love for the game to his kids, who honed their swings in grandpa’s backyard, a farm in Harborcreek, Pa. M.J, Mitch’s grandpa, hired the superintendent of Shaker Heights Country Club to build a 10,000-square-foot practice green next to a pond on the property; they added several pin positions, a chipping area and a tee about 100 yards away. A couple of times each year, a company from Cleveland would punch the green and top dress it. All four of the Bernet kids went through the junior golf program at Shaker, no surprise given their father was on the club’s board of directors and chairman of the golf committee, and their mother was one of the lead volunteers for the club’s junior programs.

“It seemed it was mandatory that if you were going to be a Bernet in Cleveland — you were going to play golf,” says John Bernet, who now lives in Wallingford, Conn.

Despite his late start, Morrie was a natural. John remembers his 6-foot-4 father’s fluid, powerful swing and massive arch. He was a phenomenal driver. He did everything else well too. As beginners, Morrie’s children were terrified to play with him. He had little patience for those who didn’t take the sport seriously, and if you didn’t bring your best, well, you’d hear about it.

Mitch started playing when he was 8, but his father told him he couldn’t play with him until he could break 100, so Mitch kept practicing. He caddied in the morning at nearby Canterbury before heading to Shaker Heights to hang out with friends and hit balls or play until dark. When he was 9 he finally recorded three straight rounds in the high 90s (barely), earning that coveted tee time with his father and two of his dad’s pals. But Mitch’s anxiety went from bad to worse after his dad pumped his drive down the middle on the par-4 opener and then holed out for an eagle 2 with a seven-iron.

“I’m thinking to myself, No wonder I gotta be good if I’m going to end up playing with him,” says Mitch, who now lives in Atlanta and plays out of the Atlanta Athletic Club. “I ended up shooting like 115 because I was so nervous.” A few years later when Mitch was 12, he and his old man teamed up to win the 1970 Father-Son Championship at Shaker Heights — clinched on the 18th green when Morrie’s trusty Bulls Eye rolled in a lengthy birdie putt. Mitch still has the trophy. It sits in his home office next to a picture of his father.

* * * * * *

If the Bernets weren’t at Shaker Heights, chances are they were at The Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, W. Va. Visiting the iconic resort required a six-hour drive for the Bernets, who booked stays for family vacations or when Morrie met with clients. Through these visits Morrie became friendly with Sam Snead, who was the long-time pro at The Greenbrier. Mitch says his father was among a group of people that first sponsored Snead, staking him the necessary funds when he started out on Tour and paving the way for Snead’s 82 PGA Tour victories. Morrie even once played a round at The Greenbrier that included Snead and an even more famous golfing figure — President John F. Kennedy.

“We would go to The Greenbrier and it was like walking in with a rock star with my dad,” says John, who estimates that his family went to The Greenbrier between 75 and 100 times while growing up. Everyone knew the Bernets in Shaker Heights, too. Morrie and Helen loved to entertain, and their home was a blissful mix of music and drinking and smoking and laughter. The couple loved Dixieland jazz and country, and even when they weren’t hosting they’d blast some of their favorites and dance all night. Years later the same music played at their funerals.

The family moved east to Madison, Conn., in 1973, when Mitch was a sophomore in high school. The once booming railroad industry had started to decline, so Morrie and his brother decided to buy a truck stop in Connecticut. In a letter dated Sept. 13, 1973, Morrie typed a thoughtful note to the head of the board at Shaker Heights, requesting his resignation. “This is a letter that as recently as a year ago, not even in my wildest dreams, would I ever have imagined that I would have to write,” he says. “But, most unfortunately it has come to pass.” Morrie continued his non-resident membership up until his death.

ADVERTISEMENT

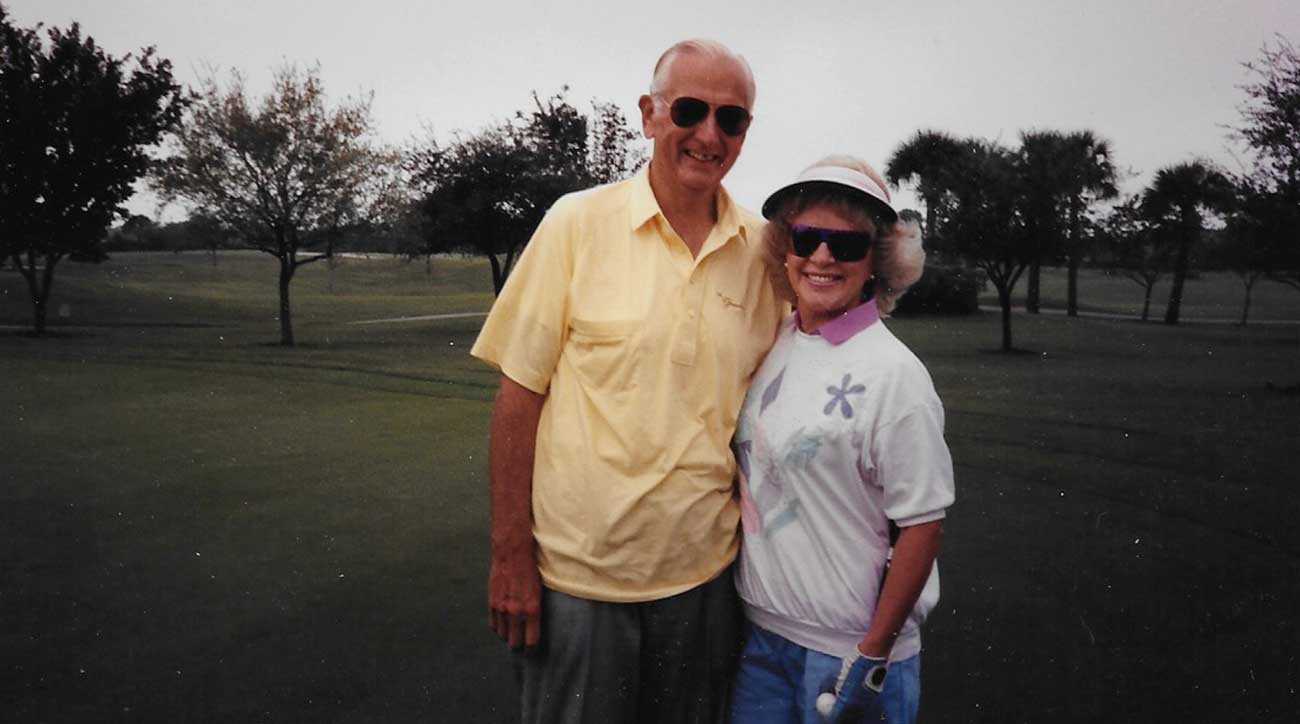

After several years in Connecticut, Morrie bought a place at Pelican Bay in Naples, Fla., in 1986, and he and Helen moved their full time in 1990. According to John, this was Morrie’s dream, “his nirvana.” They joined Club Pelican Bay, where Morrie continued to play golf, but slowly his health started to decline. He smoked two to three packs a day his whole life, and he lost a lung in 1960. He quit smoking for 16 years — missed it every day — and started again in 1976. By 1991, lung cancer was taking its devastating toll.

John was working for his father at the time, traveling between Connecticut and Florida and trying to help his dad when he could. One summer day, despite his health and to John’s surprise, Morrie wanted to play golf. So he and John went to Club Pelican Bay, which Morrie had envisioned as his golf oasis for decades to come. John knew his dad was gravely ill, and Morrie couldn’t hide it. Shades of his patented silky-smooth swing were still there, but now it cocked back and unwound in slow motion. The one-time bomber had lost his power; his physical abilities were diminished. Morrie wasn’t the same golfer anymore, and it crushed him. After struggling through the first two holes, he hit a lackluster approach to the 3rd green. He turned and put his club back into the bag.

“He told me, and I’ll always remember this,” John says, “’I’m done.’ And he sat in the cart. And he was done. He never played again. You could see the look of defeat on him. He was crushed. He was just crushed he didn’t have the physical wherewithal to play the game he clearly loved. He certainly knew that this was his mortality and it stared him right in the face. I get chills when I talk about it. It was devastating — as someone who loved him — to watch him in this great moment of defeat.”

About seven months later, Morrie died. He was 62.

* * * * * *

The Bernet kids I talked to spoke glowingly of their father. Mitch says his dad was a strict disciplinarian, sarcastic and, well, kind of a smart ass. (“I got that from him,” Mitch says.) Morrie also instilled in his children a love for the game, while using golf as his vehicle for many of his life lessons.

“He said you could always tell a lot about a person by watching them play golf,” Mitch says. “If they cheated at golf, they would cheat you in life. He told me that golf gives you the opportunity to do what is right when no one is watching. Integrity mattered to him.”

Morrie took time to get to know people, to be genuinely interested in them and their stories and to make them feel like the most important people in the world. That’s why he was beloved at The Greenbrier. He made people feel like they mattered. To him, they did.

He was generous with his golf clubs, too. He didn’t upgrade his sets often, especially his wedges and his putter, but whenever he did, he’d drop off the old ones at the local junior golf program, like the one at Madison Country Club in Connecticut, the club the Bernets joined after leaving Ohio. That’s where Morrie eventually parted with his loyal Acushnet Bulls Eye, which somehow found its way to a flea market vender named Larry, and eventually to my living room floor. It was one of two putters Morrie used his entire life.

“I never understood how he could putt with that thing,” Mitch says. “After I bought him the new putter, he still regretted getting rid of his Bulls Eye.”

The putter sat in my apartment for weeks and in the corner of my office cube for even longer. A couple of weeks ago I packed it up and sent it to a residential address in the Atlanta suburbs. A few days later, an email arrived from Mitch.

“Josh – Got the putter today. Thanks a lot for sending that down, but thanks even more for letting me share my Dad’s story. He was an incredible guy and someone that I loved and admired. Appreciate that trip down Memory Lane.”

Best 10 bucks I ever spent.

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.