He wanted to be a golfer. He trained to be a monk. He became a writer

He wanted to be a golfer. He trained to be a monk. He became a writer

Forever Seve: Four decades ago, a win at the Open Championship changed Seve Ballesteros’s life and birthed a legend

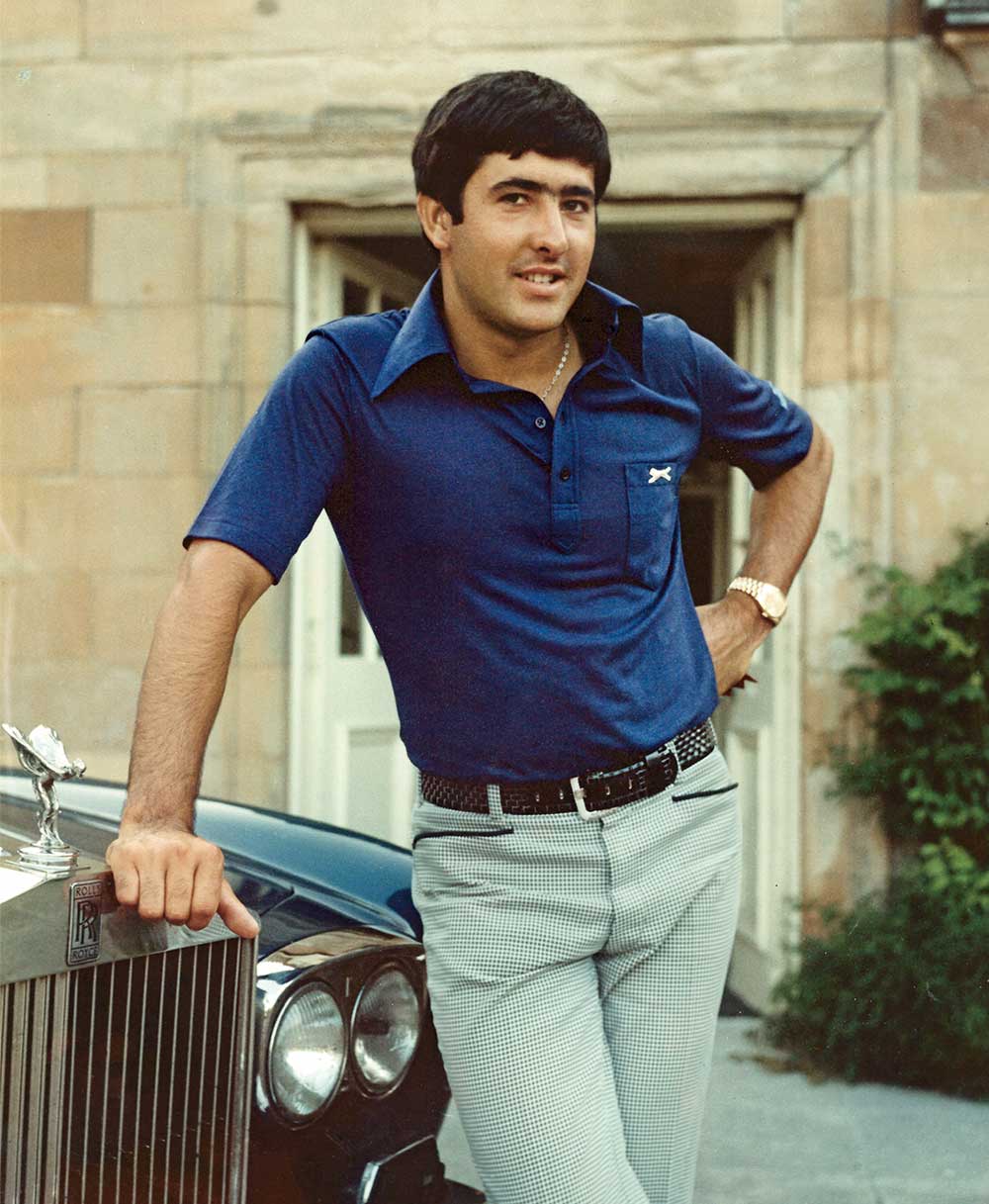

The 1979 Open Championship featured weather that was frigid even by the miserable standards of the Lancashire coast. Heading out for the final round at Royal Lytham & St. Annes, leader Hale Irwin fortified himself with two sweaters and what he delicately called “intimate apparel.” But Irwin, who had won the U.S. Open just a few weeks earlier, was quickly blown away by the wicked winds off the Irish Sea, finishing the round with a 78. That was three strokes better than the celebrated bad-weather grinder Tom Watson, who began the final round in eighth place but tumbled all the way to 25th. Jack Nicklaus made a run on that fateful Saturday—the Open wouldn’t finish on the Sabbath until 1980—as did the young Ben Crenshaw, but this glamorous duo was no match for the hot-blooded young champion who set Lytham ablaze: Severiano Ballesteros. He was a mere 22 years old but already held the gallery in his grasp. They were drawn in by Seve’s smoldering good looks and effortless style, and wowed by his prodigious talent.

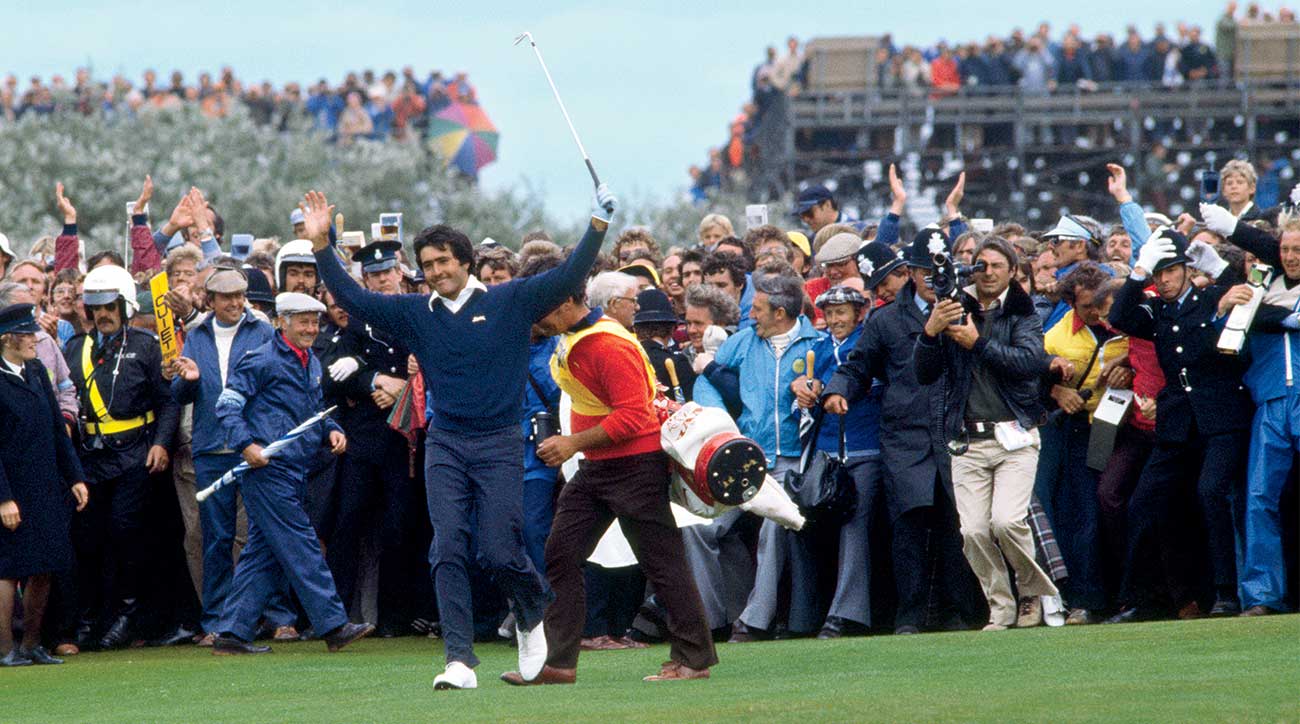

The 1979 Open was the win that began the cult of Seve, his sorcery that week having already passed into legend. Across 72 holes, he hit just nine fairways but ultimately would be the only player to break par in the brutal conditions. Lytham’s back nine played straight into the gale, and while all the other future Hall of Famers retreated, Seve came home at a full gallop, navigating the final seven holes in one-under par. “He was like a racehorse; he loved to have the bit in his mouth and to take off and run,” Irwin recently recalled. “Seve was a great frontrunner because he played without fear, or so it seemed.”

On the 16th hole, Ballesteros uncorked what Irwin calls “one of the most wayward drives I’ve ever seen from a professional golfer. I remember going to an official and saying, ‘How can that not be out-of-bounds?’ I was kind of bewildered by that.”

Ballesteros’s ball settled in a parking lot, under a blue sedan. After being granted a drop, he ripped an approach to 30 feet, then buried the putt. The Car Park Birdie iced the Open and would come to symbolize his career.

“He always brought so much flair to golf,” says Luke Donald of his boyhood idol. “People don’t remember ordinary, they remember dramatic—and that was Seve. You never forgot what he did on the course.”

Ballesteros would go on to win two more Opens (’84, ’88) and a pair of green jackets (’80, ’83), his Masters triumphs beginning a European wave of dominance that quickly shifted the balance of power at the Ryder Cup. In the years from 1927 to 1983, the U.S. had lost only twice. With Seve as the fist-pumping, foot-stomping team leader, Europe won four of the next six, and in 1997 he captained the team to yet another victory, on his home soil in Spain. Always in a hurry, Ballesteros entered the Hall of Fame in 1999 at the age of 42. A dozen years later he was gone, taken by a cancerous brain tumor. Yet nearly a decade after his tragic death, and forty years after his breakthrough at Lytham, Seve remains a protean figure. He stars biannually in the hype videos that stir the European Ryder Cup team. Donald still dresses in navy blue on Sundays in homage to Ballesteros’s trademark look. At this year’s Masters, Gary Player got a little emotional noting it was Seve’s birthday. José María Olazábal still weeps when discussing his friend and mentor. Why does Seve still matter so much?

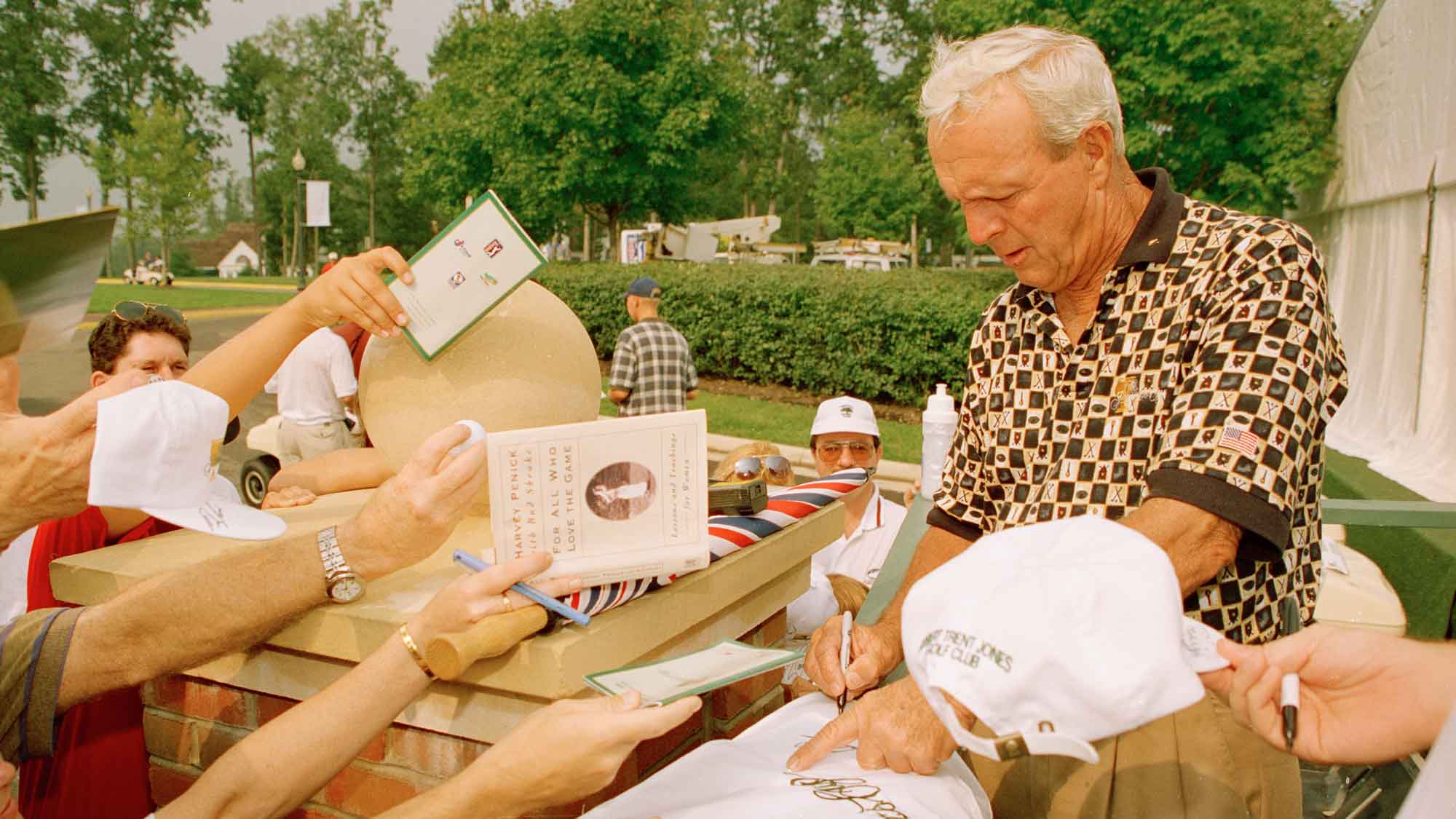

“Americans had Arnold Palmer and Jack Nicklaus, and before that Ben Hogan and Bobby Jones and others,” says Ian Poulter, who grew up watching Ballesteros highlights and who models his Ryder Cup mien after his hero’s glowering visage. “For us Europeans, Seve is all of those people rolled into one. He meant everything to us. He still does.”

Ballesteros’s appeal transcended borders. “There was a mystique about him, a presence,” says Irwin. “He was brash, he was dashing, he was a very handsome young man. He was this matador-like figure who seized everybody’s imagination.”

There is another element to Seve’s enduring appeal: “He came from a very small place and had a very humble life growing up,” says Sergio Garcia. “That he was able to go so far is one of those magical stories in sports.” In fact, it has always had the ring of myth: the son of a fisherman who taught himself the game by hitting balls on the beach with a discarded 3-iron. A visit to Seve’s hometown of Pedreña, in the northern coastal region of Cantabria, reveals an even richer story.

* * * * *

Welcome to the home where it all began,” says Manuel Ballesteros, standing in the entryway of a white-walled cottage in the green hills above Pedreña, which now has a population around 1,500, five times more than when Seve was growing up. Trim, dapper, dignified and quite spry at 70, Manuel is the second-oldest of the four Ballesteros boys. Seve was the baby. They slept in bedrooms above the livestock stables in this simple house, which was built by their great-grandparents in the 1880s, and where Manuel now lives with his wife. The boys looked after the family’s 14 milking cows while their mother, Carmen, ran the household and tended the garden, and their father Baldomero fished and worked the land. It was a simple life enriched greatly by a quirk of fate. “I hesitate to make this comparison, but Pedreña was like the St. Andrews of Spain,” says Seve’s old friend Agustín Mazarrasa. “In this country there were very, very few golfers. The sport was basically unknown. But Pedreña was different. Everybody played golf. They knew the game. They spoke golf in the bars and everywhere else. It was a way of life.”

This had everything to do with Pedreña being across the bay from Santander, a beautiful, hilly city hard by the water that evokes San Francisco. The Spanish royal family vacationed in Santander, staying at the Palacio de La Magdalena. King Alfonso XIII was a keen golfer, so he ordained that a course be built for his holidays. The rolling hills and water views in Pedreña were deemed ideal. Nearly 300 small farms (including the one owned by Seve’s maternal grandfather) surrendered their land, and Harry Colt was brought in to design the course. Real Golf Club de Pedreña opened in 1928, with the king himself serving as an honorary president of the club.

The Ballesteros home was so close to the course that in the evenings the boys would hit balls from their sloping front yard down the hill and over a rock wall to the second green. During a recent twilight, Manuel pantomimed the shot, his action still smooth despite the tweedy blazer he was wearing. “I could get there with a 7-iron,” he said. With a chuckle he added, “Of course, those trees were much, much shorter back then.”

The brothers caddied at the club—Seve started at age 6!—and learned the game from the head pro, their maternal uncle Ramón Sota, a terrific player who tied for sixth at the 1965 Masters. Manuel confirms the legend of Seve’s hand-me-down 3-iron but clarifies that it was only the head. Seve would scavenge for the correct sized sticks, jam them into the head and then soak the makeshift shaft overnight in water so the wood would swell and fit tighter within the hosel. If he was lucky the shaft would last two days before snapping. Caddies were allowed to play Real Pedreña just once a year, so Seve would take purloined balls and create his own course, tying a handkerchief to a branch and planting it in the earth. Sometimes he made these holes in a meadow in the hills, or he would go to the small beach near the marina in Pedreña. If he wanted a more expansive playing field it was a 15-minute walk to Somo, one of the world’s great beaches, framed by scrubby dunes not unlike what he would later encounter at Royal Lytham. It is part of the Seve folklore that he would sneak out at night and play Real Pedreña by moonlight. In his autobiography, he wrote of how these secret rounds shaped his feel for the game: “It was a very strange experience to walk around a golf course at night, because all the reference points that help estimate distances vanished. I knew where the shot was heading from the way my hands felt the hit and from the sound the ball made when it hit the ground. By practicing at night I learned to feel the grass under my feet, to measure distances intuitively and adjust the power of the strokes I wanted to make.”

ADVERTISEMENT

By the time he was 10, Seve was good enough to finish second in his flight in Real Pedreña’s cut-throat caddie tournament. When he was 12 he shot 79 to win it.

“At a very early age we could see Seve was a magician,” says Mazarrasa, a former club president who first shot his age when he was 67. “We were used to high-level golf in Pedreña. Seve’s older brothers were very good golfers. Of course, Ramón Sota was one of the best players Spain had ever produced up to that time. And over the years probably 30 or more men came out of Pedreña and went on to play or teach professionally. But Seve was different. He had a gift from God. He would go into a bunker and hit his ball closer to the hole with his 3-iron than we could with a sand wedge.”

Seve’s development accelerated when he dropped out of school at 12. The next year he created a stir by shooting 71-65 from the tips to win the caddie tournament’s toughest flight. (It was also at 13 that Seve, for the first time, beat his brother Manuel, who was eight years his senior and already a touring professional.) Recognizing that a special talent was in their midst, the club stewards allowed Seve unlimited playing privileges.

By 1972, Manuel had reached the European Tour, beginning a decade-long run during which he would finish inside the top 100 on the Order of Merit. (He won a handful of times, his greatest victory coming at the 1983 Timex Open, when he trumped Nick Faldo head-to-head.) After dominating regional tournaments, Seve joined his brother on the Euro tour in 1974, at the age of 16, staked by a wealthy Madrid physician.

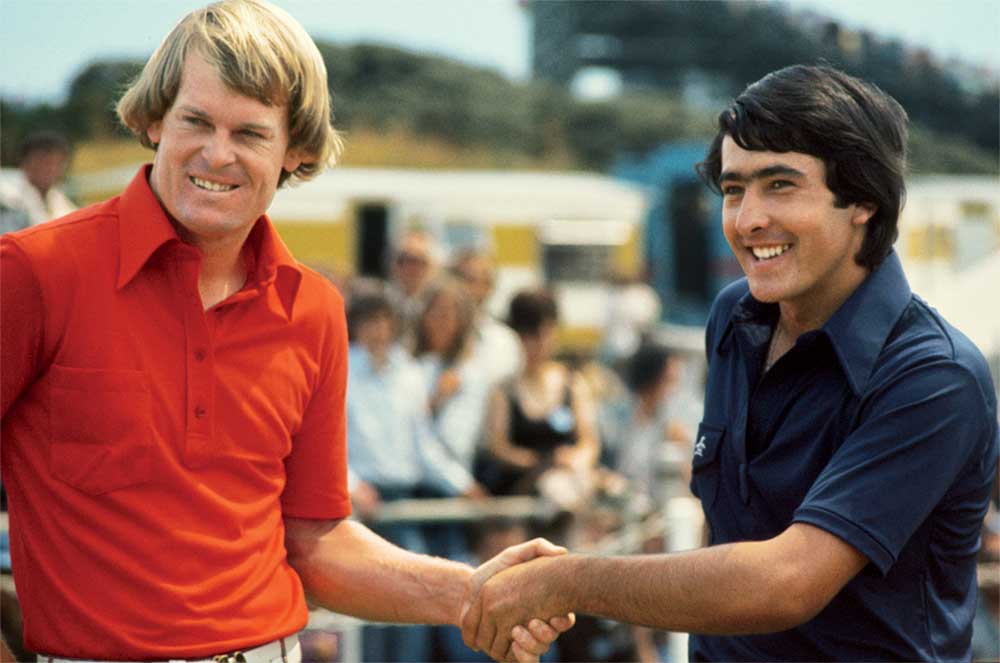

A year and a half later, at the 1976 Open Championship, Seve introduced himself to the larger golf world by storming to the 54-hole lead. Not for the last time, Seve got in the head of his playing partner, in this case Johnny Miller, who said, “I let his scrambling get to me, and my own game went out of control. He’s a good kid, though. He wears Johnny Miller slacks.”

They were paired together again for the final round at Royal Birkdale. The weather was so freakishly hot and dry that brush fires broke out periodically during the week, and the course was baked to a crisp. In the exacting conditions, Seve lost his cool and shot 74, including a triple-bogey on the 11th hole, to get run over by Miller, who came home in a scorching 66. Afterward, the young prodigy wept in his brother’s arms. Dan Jenkins, writing in Sports Illustrated, was not impressed: “The world may not hear more from Severiano Ballesteros, he of the strong left grip, the wristy swing, the whiplash of a full swing and the nose for always finding the golf ball in the bushes.”

He could not have been more wrong. Only a few weeks later, Seve broke through to win his first professional tournament, the Dutch Open, and he went on to top the Order of Merit for the ’76 season. Over the next two years he piled up seven more victories to establish himself as the European Tour’s alpha. Although he racked up five top-20 finishes in the majors, Seve never threatened to win any of them, and this nettled the young prodigy. “Since he was 15 I was telling him he was the best player in the world,” says Manuel, who shared a room with his brother on the road. “He was finally starting to believe it. But he knew to gain that recognition he had to win the biggest tournaments. That desire was building inside of him. It was like a storm gathering.”

It was at the 1979 Open Championship that Seve finally unleashed all of this want and will. Back in Pedreña there was no way to watch the live telecast, so Sota called a friend in England to get play-by-play over the phone, which he shouted out to the crowd that had gathered in the pro shop. “We were hanging on every word,” says Ito Chaves, who married Seve’s cousin and became a close friend. “When he finally won there were great shouts of joy. For a boy from this village to win the biggest tournament in the world? It was a great occasion.”

The golf world would never be the same.

* * * * *

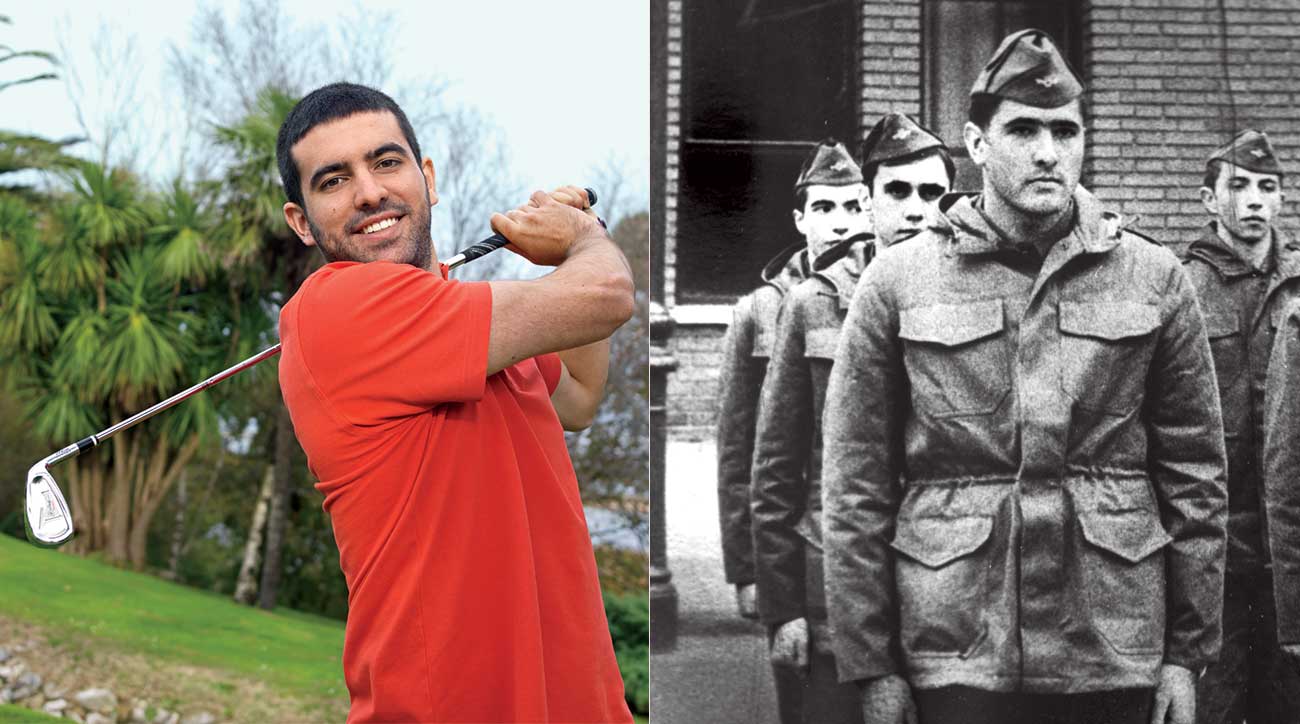

The headquarters of the Seve Ballesteros Foundation are in a tall building in downtown Santander, a thriving financial center that marries the old and the new: The bustling main boulevard bears stone markers for the path of the Camino de Santiago, the annual pilgrimage that ends 500 kilometers to the west in Galicia, at the shrine of the apostle St. James the Great. The Foundation’s keeper of the flame is Rosario Sordo, who has devoted most of the last three decades tending to Seve and now his memory. His office has been preserved exactly as he left it, and atop the sleek table Sordo plops down a vertiginous stack of folders containing a thousand or so loose photographs of the great man. To flip through the photos is a journey back in time: Seve brooding in his army uniform in a manner that calls to mind Elvis Presley; photo shoots on Somo Beach, recreating his youthful hijinks; tender candids with his sons Javier and Miguel and daughter Carmen; mingling with kings and Hollywood stars, none of whom could match his charisma. Sordo often works alone in the expansive office, which is crammed with memorabilia and the blueprints and photos of the three dozen courses Seve designed. “People ask me if I ever feel alone,” she says. “But I am not alone. Seve is here with me. I still feel his spirit powerfully.”

Seve is everywhere in this corner of Cantabria. The airport in Santander is named for him. In a park in Pedreña there is a faux-Swilcan Bridge and bronze statue capturing Seve’s iconic fist-pump that followed his victorious birdie on the 72nd final hole of the 1984 Open Championship, at the Old Course. The clubhouse of Real Pedreña—which was once used as a summer residence for Queen Victoria Eugenia—is a veritable museum devoted to the golf royalty who emerged from the club. At La Trainera, his favorite restaurant in Pedreña, there are numerous photos of Seve, as well as old black-and-whites of his father, a champion rower who brought much pride to Pedreña in the annual competitions between the villages along Santander Bay. The proprietor, Manuel Ocejo, settles into what was Seve’s favorite chair and speaks warmly about his old friend. “He would always come in with his family,” he says. “He loved them dearly. And he would come in early, when there were few other diners, because privacy was very important to him.”

Asked to name his favorite customer’s favorite dish, Ocejo comes up empty. “Seve liked simple food,” he says. “For all of his fame, he was a simple man.”

And yet he built the grandest house in Pedreña, atop the same hill where his boyhood home sits. Seve’s children are grown now and live in more cosmopolitan places. His marriage to Carmen Botín—the daughter of one of Spain’s wealthiest men—ended in 2004, seven years before his death. The home in Pedreña is now used for holidays, and to remember. “We keep it exactly as it was,” says Seve’s son Miguel, sitting in the formal living room, “because when we are here it allows us to feel closer to my dad.”

Miguel, 26, tried for a short time to play golf professionally, and Javier, 28, is still at it. Their favorite place to play will always be the par-3 course their father built on the grounds of their estate, with wicked greens, narrow chutes between the trees, and tee markers that are a silhouette of Seve in mid-fist pump. “Anything under par is a good score,” says Miguel. “Even for my dad.” Surprisingly for such a wild driver of the golf ball, Seve loved trees, and he personally planted dozens of different varietals on the grounds. His favorite was a big magnolia that always made him think of Augusta. His wish was to be buried beneath it; the spot is now marked by a simple black granite plaque.

Next to the living room is an antechamber filled with Seve’s old clubs. All the lead tape, different grips and custom grinds attest to his endless search for the right feel. Well before he was 40, Seve saw his game tragically vanish, owing to injuries and an obsession with mechanics that robbed him of his gift. But here in Pedreña he lives on forever in his prime, in numerous photos and paintings that only begin to capture his magnetism. The centerpiece of Seve’s home is its beautifully staged trophy room. Your eyes go immediately to the two green jackets that were somehow smuggled out of Augusta. Those wins helped make him a star; he was the youngest-ever Masters champion until Tiger Woods came along. The trophies from his record 50 European Tour victories crowd the cabinets. Look closer and you’ll find the replica of the Claret Jug from Seve’s breakthrough at the ’79 Open. After all these year, it still glitters.

ADVERTISEMENT