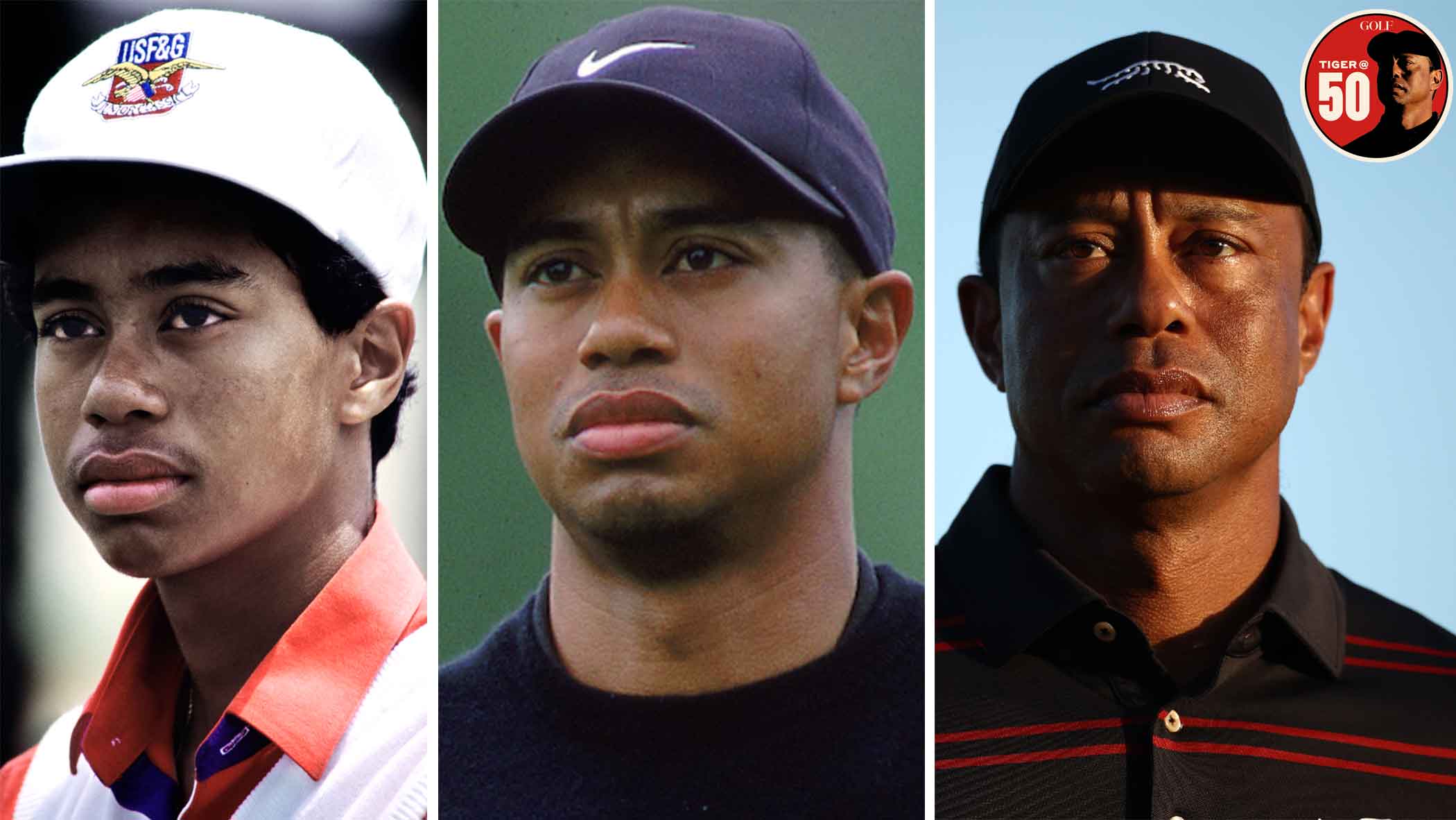

Tiger Woods has lived his first two acts. His third act is a work in progress

Tiger Woods has lived his first two acts. His third act is a work in progress

To Russia with Love: The story behind Russia’s first 18-hole course is stranger than fiction

Two decades in the making, Moscow Country Club, Russia’s first 18-hole golf course, debuted on the world stage 25 years ago this month. And the story of its creation — from Gorbachev and glasnost and swinging cops to grounded cosmonauts and mushrooms and vodka — is stranger than fiction.

The 1960s began with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev banging his shoe — definitely not a FootJoy — on a desk at the United Nations. A couple of years later came the Cuban Missile Crisis, which was as close to a nuclear holocaust as the world had come before or since. The Cold War continued in full freeze until the end of the decade, when U.S. President Richard Nixon, his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, and Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, tried to thaw things out.

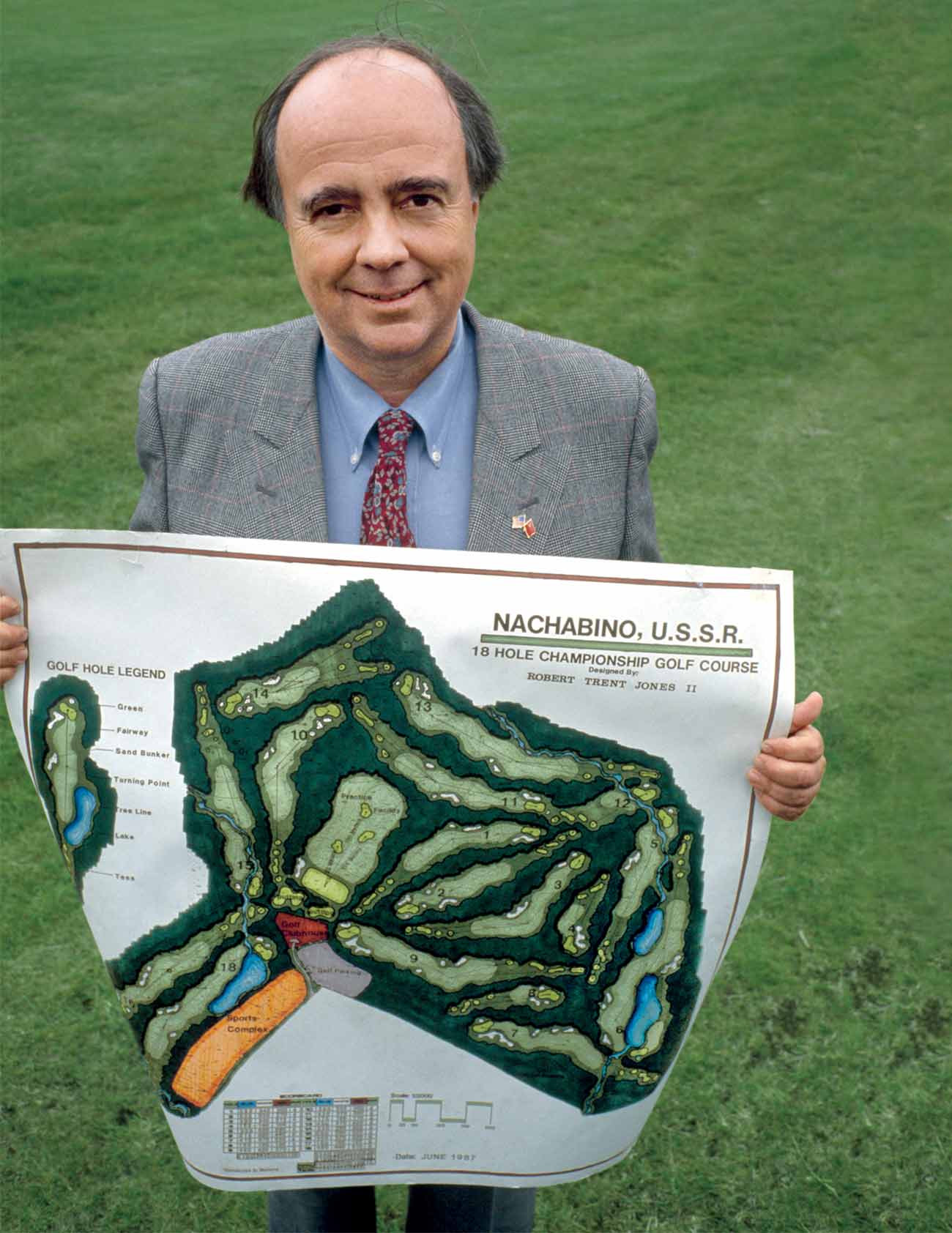

Détente between the Soviets and the U.S. took on many forms. Perhaps the most surprising was plans for an American-designed 18-hole golf course on the outskirts of Moscow, the first in all of the Soviet Union. By the time it was done, perestroika and glasnost had cleared the way for playing golf — and the Soviet Union had dissolved. Here, some of the key players on one of the unlikeliest golf course projects ever share their recollections.

1. The Tsars Align / Fall 1973

Robert Trent “Bobby” Jones Jr., celebrated course architect and son of legendary course designer Robert Trent Jones Sr.: [American business tycoon] Armand Hammer, who was chairman of Occidental Petroleum, had a longstanding relationship with the Soviet Union’s oligarchs. Having gone over there at the beginning of what was later called détente, with Secretary of State Kissinger’s delegation, Dr. Hammer made a statement that if the Soviets were going to open up their closed society to Western and Japanese business, they needed two things: a golf course and a Cadillac. I read that in the New York Times. So I called Occidental’s office and identified myself to a manager of some kind. I’m waiting on hold, and suddenly I heard, “Armand Hammer here.” I was actually speaking to the chairman!

I said, “Do you want to do a golf course, and can we help you?” He said, “Why should I take you?” I said, “Well, I’ve been to the Soviet Union. After I got out of Yale, I went on a tour.” He said, “That’s unique.” Then he said, “Shouldn’t we use Arnold Palmer?” I said, “My father’s much more famous about building golf courses. Arnold tends to play.” Dr. Hammer didn’t know much about golf. This was a Thursday. He said, “I can’t see you tomorrow — be here Monday morning.”

Meantime, he had a friend on the USGA Executive Committee named Bob Dwyer, who was a timber man. The Soviet Union had lots of timber, and he and Dr. Hammer were trying to harvest and sell Siberian timber together. Dwyer and my father met a few months later at a USGA meeting. He convinced my father, who was a little reluctant to go, that Dr. Hammer was very well connected in the USSR. The following June, we all flew in a private plane that Dr. Hammer had. Onboard was a Soviet in his military uniform, to make sure we didn’t deplane to do anything weird.

We met with the mayor of Moscow, Vladimir Promyslov, and the foreign minister in charge of properties, called UPDK, a man named Vladimir Kuznetsov. Kuznetsov had been posted as ambassador to Malaysia, where he learned to play golf and would play with the U.S. ambassador at the Royal Selangor Golf Club so they could have backchannels about the Vietnam War. He’d become hooked on golf. My dad and I went skinny-dipping in the Volga River after too much vodka. My dad didn’t drink much, and I drank too much that day. But over time we made friends with these people. We didn’t see it as a commercial opportunity. It was an adventure.

Over a five-year span, from 1974 to 1979, Jones Jr. and Sr. made several visits to Moscow to look at potential course sites.

Jones: Eventually, they chose the site, Nakhabino, about 45 minutes from Red Square, because it was in the woods and nobody would see what they were doing. They didn’t want anybody to know they were making a golf course. There was no golf in the Soviet Union. It was considered an English sport and symbolic of the enemy, meaning the English, who had invaded and held Murmansk during the revolution.

November 1979

Jones Jr. went with Kuznetsov to see the Olympic Stadium, where Moscow would be hosting the 1980 Summer Olympics.

Jones: I was walking with Mr. Kuznetsov, and it starts snowing. And because they had a SALT treaty that our Congress did not approve, I said, “How are things between our two countries?” He said, “They’re colder than these few snowflakes. And by December, they’ll be very cold.” I took that as a sort of metaphor. But what he was hinting at was the Soviets were about to enter Afghanistan.

The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979, which led to a freeze in cultural and sports exchanges. The Moscow Country Club project was mothballed for another six years, during which time Jones Sr. left the project. Then Mikhail Gorbachev came to power.

Sam Nunn, U.S. Senator from Georgia: The first time I met Bobby was in the ’80s. I was a guest out at Cypress Point. A friend of mine from Rand Corporation introduced us. It rained about 14 inches that Saturday and Sunday, so we only managed to play maybe nine holes. But I got to know Bobby that weekend.

He travelled all over the world and was involved in a lot of countries where the East-West issues were front and center. That was what I spent a lot of time on, so we stayed in touch. He kept me informed on observations he’d make about various countries. The common denominator was golf, but he had a very keen interest in, and understanding of, many of the issues that we were dealing with politically in that era — the Soviet Union as well as with other countries, such as the Philippines when [President Ferdinand] Marcos’s leadership was coming under great assault by his own people.

There was a huge amount of tension — anything about the capitalist world was condemned in the Soviet Union, and golf would be right there at the top echelon of those types of symbolic issues. The chances of building a golf course in the land of the adversary, let alone the land where capitalism is damned, was very unlikely. Still, I took it seriously, because I felt the Soviet Union was going to have to change, if nothing else, for economic and investment purposes. And as I got to know Bobby, I came to realize that he doesn’t understand the word “impossible,” either in Russian or English.

Jones: George Shultz was a personal friend of mine, a member at San Francisco Golf Club, as I am. We played golf occasionally. When he became Secretary of State under Reagan, in 1982, he knew about the Moscow golf project and how it had been put on the back burner. In late 1986, he told me, “Bobby, get ready. That project may have some importance.”

January 1987

Jones is in Moscow, quietly negotiating terms of the golf course commission with the UPDK.

Jones: One night, I was walking by myself. There was no danger, walking the streets in Moscow, because crime was punished severely. But you couldn’t find good food.

Craig Copetas, a Moscow-based journalist: It was about 1:00 in the morning, and I had gone down to Old Arbat Street because I needed to look into the window of an antiques shop there for a story I was working on. No one was in Moscow at 1:00 a.m. in those days; it was completely vacant. There’s one of these Moscow mists in the air, kind of a frozen fog. And out of this mist, from around the corner, comes this guy wearing a baseball hat. He comes up to me and says, in English, “Do you know where I can get something to eat?” I said, “This is Moscow. Are you a tourist? Are you lost?” He says, “No, I’m here building a golf course.”

Now, old Moscow hand that I am, having heard every conceivable farfetched tale you could imagine, my jaw dropped. I looked at him and I said, “And I thought I was crazy.” I didn’t believe him. This made absolutely no sense. But I was intrigued. I said to him, “Well, I happen to know an illegal place down the street that stays open quite late where we can get some khachapuri — it’s like a Georgian pizza.” We went there and spent the whole morning talking, and he explained to me the project’s history. I was in complete awe.

June 1, 1988

A deal to create Moscow Country Club was announced at a summit meeting in Moscow, with a two-year contract between Jones’s firm and the Soviet foreign ministry (via a “techno-export company”).

Jones: Our plans had been approved by [Minister of Foreign Affairs Eduard] Shevardnadze, and George Shultz actually did the final [U.S.] approval of the project. Their contract was promptly agreed to, but ours was not. In the contract I submitted, I put a plan in it that had a legend: tee, fairways, greens and bunkers. The guy reviewing it in the Commerce Department was not a golfer. He said, “Oh, I had to send it to the Defense Department. You have a thing of known military significance — bunkers.” That held it up.

Blake Stafford, Jones’s business lawyer: We had to do some redesign of the irrigation system, because there was a computer control to regulate the irrigation heads. They also said, “What are these bunkers?” I said, “They’re depressions in the ground you create to catch errant golf balls.” They said, “It sounds like something from a battlement of some kind.” I said, “Nope, it’s not for fighting wars, it’s for fighting golfers.”

2. Coming to America / November 1988

Jones invited a small group of Russians — among them, Deputy Foreign Minister Ivan Ivanovich Sergeyev and assorted Soviet engineers and architects — for a two-week U.S. tour to learn more about golf. The itinerary included a visit to USGA headquarters in Far Hills, N.J., and course tours in and around Washington, D.C., Chicago and California’s Monterey Peninsula.

Jones: When the Russians had a party, they had a party. Once you broke the ice with them, they were very warm. In Moscow, they took my son Trent to the circus. They took my wife and me to the Bolshoi Ballet. We tried to return the same hospitality when they came to see us in the States.

Bill Pollak, a friend of Jones, and a lawyer and sports agent: The Russians came to Washington a week before Thanksgiving. I asked them how familiar they were with the traditions of Thanksgiving, and it was very little. They wouldn’t still be here for the holiday, so my wife and I did a complete Thanksgiving dinner for them a few days early. It was wonderfully colorful and joyful. They combined our Thanksgiving traditions with Russian traditions — singing and drinking and just thoroughly enjoying eating turkey and all the trimmings. I’ve never seen Thanksgiving with more drinking festivities.

Jones: All but one of them had never been out of the Soviet Union. They were amazed. When they went to Spanish Bay, which had just opened, they said, “My gosh, these rooms are so big. Shouldn’t we invite some homeless people?” And those little vodka bottles in the minibar, they were all consumed. I said, “Listen, don’t use those little ones. That’s expensive. I’ll get the big one.”

We went to a football game, Cal versus Stanford, big game. The Russians said, “Oh, we’re going to be for the [Cal] Bears, like the Moscow bear.” I said, “I’m a Stanford guy. You can’t be for the Bears.” “No, we’re going to be for the Bears.” Then one guy kept saying, “I don’t know anything about this game, but I really like those dancing girls” — the cheerleaders. It was a very big deal, in terms of détente, and cultural and sport exchange at the highest levels.

Stafford: There were a lot of really, really fun times, and the Russians we dealt with were completely enjoyable people with very similar senses of humor.

3. Breaking Ground / 1988-1993

The course building began in the winter of 1988; Jones invited Antti Peltoniemi, a Finnish golf course contractor he’d worked with previously, to join the project the following year, in part because he could import a needed bulldozer.

Antti Peltoniemi: When we first started construction, we had mainly Finnish and other experienced foreign workers building the log houses, the clubhouse and the golf course. There were 22 nationalities represented on the workforce, including somebody from Ecuador, who was the farthest away. I think it’s pretty much the same in every country where you haven’t had golf courses. The local workers or contractors think that they’re just moving dirt, then you seed it, and that’s the golf course. But throughout the years, we were able to train and teach those Russian nationals to build and eventually maintain the course. We started cooperating very well. They were willing to learn and are quite quick to learn if you explain what you are doing. By the end, we had only a couple of supervisors from Finland.

Copetas: I vividly remember one evening, long before the course was completed, we were in my car, along with two American golf-course shapers. For some reason, Bobby had all these golf clubs on the floor in the back seat, and there were more in the trunk. We’re driving, and two Russian cop cars stop us. What the shapers knew about Russia is from, like, hiding under desks. They’re scared to death. They think they’re going to prison. They’re cursing, they’re yelling, they want to go to the Embassy. I’m trying to calm them down. Bobby, in his inimitable way, gets out of the car and starts talking to four Russian police officers in English, thinking they’re going to understand him. They’re looking at him like, “Who is this guy in the baseball hat?” One of the cops shines his flashlight in the car, and he sees these golf clubs. Of course, he’s never seen a golf club before in his life. They take these things out, they’re looking at them, they don’t know what the hell they are. And Bobby proceeds to give one of the cops a lesson in how to swing a golf club, in the middle of the night in Moscow.

ADVERTISEMENT

Peltoniemi: Because Star Wars [the Strategic Defense Initiative program] kind of ended during the Reagan time, one of the superintendents on the golf course was a cosmonaut. He was a guy who was supposed to go to space, but then because the program fell away, he came to work on the golf course. We trained him in Finland, and Bobby trained him in the United States. So that was interesting.

Jones: When we were clearing the forest, we came upon, literally, a bunker that you could see had been shoveled out, and the trees had grown up around it. I asked, “What’s this feature?” They said, “Oh, that’s where we stopped the Nazis, right there,” as they were marching toward Moscow. We left it as a symbol of turning swords into plowshares.

Challenging weather and financial problems posed significant hurdles, but it was political unrest that nearly did the project in.

Jones: We had nine holes that were just grown in when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 — and then nobody came to work, nobody. Antti got his Finnish guys, and I got one of our guys, and we maintained the course for them for about a year for nothing, just to keep it alive. We always felt that if the course ever stopped, the new manager would let it go back to nature.

Copetas: Bobby saw it as his patriotic duty to bring Nakhabino to completion. And he had a lot of friends in Russia, too. Because of this, he showed a patience that very few others ever did when dealing with the Russians… When Bobby came to Moscow — and I saw him on just about every trip — the officials at UPDK, who were dyed-in-the-wool Soviet apparatchiks, treated Bobby with a courtesy and respect and curiosity that I can honestly say I never saw with any other American there doing business.

Peltoniemi: Before you start seeding, there are small rocks or stones on the ground. You have to pick them up, so that when you start mowing and are cutting the grass the blades won’t get ruined. At the end of finishing the course, our boss, the site manager, went to talk with the colonel at a military base close by. About 100 Russian soldiers came over and walked each hole in a line, picking up all the small stones.

4. Open For Business / September 1993

A nine-hole tournament takes place in 1993. It’s exclusively for Russians, to ensure that the first champion is a native.

Copetas: The one thing that the Russians demanded from day one was that once the club opened, they wanted a Russian golf pro, of which there were none. So the Russians did some kind of hunt through the sports academy to find anyone who had any knowledge of golf whatsoever, and they found this kid and made him the golf pro. I asked him, “How did you get involved in golf in Russia, where there’s no golf?” He said that prior to the club opening, he had been on an exchange program in Florida. One morning, he woke up very early and decided to take a walk. He wanders into this beautiful park area. All of a sudden, he hears voices screaming at him very loudly. And he doesn’t understand English that well. He looks up in the air and sees this white sphere coming at him that hits him in the head and knocks him out. He took that as a sign from God that he should learn about golf. And thus was born the first Russian golf pro.

The inaugural Russian Open championship, a 54-hole event, takes place in September 1994. It features a mix of accomplished players and not-so-accomplished players.

Jones: Speeches were made. The local mayor, who knows nothing, gave a long-winded speech. Then Michael Bonallack, who had come from the R&A to help open the course, was invited to speak. He got up and said, “On behalf of the Royal and Ancient Golf Society that was founded in St. Andrews in 1754, we welcome all of the people of Russia to our sport,” and sat down. That’s it. I thought that was perfect. Then Deputy Foreign Minister Sergeyev got up and said, “Comrades, I am the trained engineer responsible for the public health of our country. Because of perestroika and glasnost, I can now speak openly. Our entire country is an environmental cesspool. But here, at Nakhabino, there is one garden growing. There is hope,” and sat down. Best speeches I ever heard.

Peltoniemi: My brother Mikko, whose handicap at that time was 20, was playing in the third flight. He ended up making a hole-in-one on the 16th hole. Flew a 5-iron straight into the hole. There were three Russian TV stations there because it was the first Russian Open, and they were interviewing him because his hole-in-one was the most fascinating stroke of the tournament. They asked my brother, “Have you been playing on the American tour?” He said, “Yes, twice” — because he had been with me in Florida, where we played together two times. They asked, “How did you do?” He said, “I won once,” because he beat me one of the two times. They think he is a winner on the PGA Tour! It was a very young golfing culture at that time.

We had a huge celebration in the evening, and everybody wanted to toast vodka with Mikko. He was carried to the hotel because he got so drunk. The next day, he was playing in another early flight, because his 102 was not that good a score. When he came to the same hole, No. 16, there was one TV crew that came to see. And he hit it to about two inches from the hole! The TV crew said, “You did quite well there.” My brother, fooling around a bit, said, “Well, the wind was kind of circulating, so it was hard to shoot.”

At the end of the day, after the tournament, they had a summary about the tournament on TV. They said, “Best score was by the American Steve Schroeder…but clearly the most astonishing and the most remarkable player was Mikko Peltoniemi, because now, another day, he almost made hole-in-one again, and nobody else got even close to the hole.”

Steve Schroeder, chief business officer, Robert Trent Jones II Design (currently CEO of Poppy Hills): I’d played in two U.S. Opens, but I hadn’t played any serious competitive golf since my last Open in 1990. At Nakhabino, I had a good second round, something in the 60s, and I want to say I won by 4 or 5. The night before the last round, we experienced a major rain and played the golf course in conditions that I would describe as being along the lines of the San Francisco City Golf Championship — which is, it doesn’t matter how hard it rains or how wet it gets, you’re going to play on. We played that last nine holes in this downpour, and I’ll never forget, there’s a picture of the R&A’s Mike Bonallack hitting a bunker shot with his bucket hat on and his tongue hanging out. You just see water and sand going everywhere.

Jones: On one of the holes, there was a group of people picking mushrooms in the rough. Bonallack had to make a local rule on the spot that if your ball gets picked up by one of the mushroom hunters, you can drop without penalty.

The European PGA Tour granted the Russian Open winner a spot in the Sarazen World Open field for two years.

Schroeder: That was a really cool acknowledgement of the magnitude of the event, which subsequently became part of the European Challenge Tour. It was the lift in the wings for Russia being acknowledged in international golf. For me, I actually made the cut my second year in the World Open and got to play in a twosome with Fuzzy Zoeller on Saturday.

Jones: We got a golf club that was given to us by a metallurgist who had worked in the Soviet missile program. He had taken the titanium from an ICBM and replicated a Big Bertha and gave it to me. I later gave it to President Clinton. He asked me, “Bob, are you sure it’s not radioactive?” And I said, “I have no idea.”

5. Postscript

Nunn: I did go to the club once. It wasn’t during the early stages, and Bobby wasn’t there. I just had a chance to put my feet on the ground for maybe a half-hour. My thoughts were that things really are changing, because in previous eras in the Soviet Union, anyone sponsoring such a project would be in jeopardy not just of their work, but of paying a long-term visit to Siberia.

Jones: Doing Moscow Country Club enriched my life enormously. Was it a challenge? It challenged every aspect of my essence as a human being. You had to call a lot of audibles. You knew what the goal was, but how you got there was completely new.

I’ve been back a few times. In 2008, they invited Antti and me to come back. They planted a tree in honor of my father, who’d passed on, for his memory, and one in my name, honoring the family together. And they gave me a medal from the charitable organization for humanitarian service and the foreign ministry. It’s beautiful, emblazoned with a starburst and what looks like diamonds on it. I said to my host, “Is this real gold and diamonds?” He said, “How can you ask? Of course, of course.” Of course, it isn’t.

Still, it’s a big deal to them and to me, too. It’s like, “You’re helping the Russian people in some fashion.” It’s like a trophy of friendship. It’s on my mantle, and it’s very special.

The Moscow CC Today

The semiprivate club currently has more than 400 members. More than 14,000 rounds were played on the course in ’18. The club hosts a nine-hole members’ winter tournament using red balls. The 2018 VTB Russian Open (Senior) Golf Championship on the Staysure Tour (formerly the European Senior Tour) was contested on the course. It was the only international pro tournament in Russia last year. Stay-and-play packages are available, starting at 12,000 Russian rubles per person, which includes accommodation at a 5-star hotel. Go to mccgolf.ru and mcc-hotel.ru for more information.

ADVERTISEMENT