2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

2025 CJ Cup Byron Nelson payout: Purse info, winner’s share

How a pilot flying high above Augusta captured 2019 Masters photos unlike any other

Masters Sunday a year ago did not present ideal conditions for either tournament organizers or the field. An incoming storm cell forced the green coats to push up starting times, and down in Amen Corner the swirling breezes made club selection for Tiger Woods, Francesco Molinari and Brooks Koepka about as fun as a tax return. But that was nothing compared to what David Dobbins was negotiating in the gloom more than 1,000 feet above Augusta National, at the controls of his Cessna 172.

With gusts in excess of 40 knots, Dobbins’ plane was getting batted about like a dinghy in the North Sea. Complicating matters further, officials at Bush Field, the local airport, had switched up the runways, meaning incoming flights were in closer range to Dobbins’ plane than he would have liked. None of this would have posed much of problem for a veteran pilot zooming through the area, but Dobbins, a 60-year-old former U.S. Army contractor who runs a flight school in Augusta, was on a different kind of mission: capturing aerial video and photography of the final round of the 83rd Masters.

Dobbins had been shooting the event all week, but not in any official capacity. His company, Eureka Earth, is aiming to launch an aerial imaging service that would allow paying app users, in real time, to control cameras clamped to an army of small aircrafts across the U.S. The Augusta Chronicle characterized Dobbins’ business as “Uber for aerial imagery.” (Cynics might call it Big Brother on-demand.)

Dobbins’ Masters patrol was his second such expedition; he also shot the 2018 tournament. But in 2019, he added a new wrinkle. As a proof of concept for his burgeoning start-up, Dobbins broadcast a live web feed from a high-powered camera he encases in a pod beneath his plane. “My team in our office downtown could manipulate the camera, while a technician in the back seat of the plane pushed out the live feed,” Dobbins said the other day. “Lots of new things coming together at once.” (The experiment wasn’t particularly successful; the image quality in the feed was poor, Dobbins said, because of turbulence and inadequate bandwidth.)

Augusta National hasn’t protested Dobbins’ flyovers, or if the club has, Dobbins hasn’t heard about it. “I expected a call from them, I really did,” Dobbins said. “In fact, I’d welcome it. I could be useful to them.”

An Augusta National spokesperson declined to comment.

Despite flying on the cusp of the 1,000-foot legal limit, Dobbins’ plane hasn’t appeared to disturb the peace at the tournament, which might explain why the club has remained mum. (Dobbins said he alerted both local law enforcement and air traffic control in advance of his flyovers.) “That was our objective — not be noticed,” he said. “Occasionally I can tell when I’m making too much noise.” Earlier this week, for example, Dobbins said he was cruising over Augusta National, taking photos, when a gardener tending to a flower bed in front of the clubhouse “looked up and right at me.”

“I can tell when I’m being heard,” he said.

Keeping his bird quiet is no small task, especially in the kind of high winds he faced during last year’s final round. But that’s where Dobbins’ decades of flying experience pays dividends. There’s an artistry to his craft.

“You’ve got waves of air, just like waves in the ocean — it’s pulling me up and down and I’m trying to work within that at a critically slow speed and low throttle setting,” he said. ”When I get the sinking air, instead of adding power to stay at altitude, which would make me more obvious on the ground, I just turn away from the course and let the plane descend into an area that’s not as populated, where the altitude is not as restricted and then I can climb back up and come back over the course at my patrol speed.”

“I’m giving away some of my secrets now,” he said with a laugh.

ADVERTISEMENT

While all this is happening, Dobbins is also managing another piece of equipment: the Canon with which he shoots from his pilot seat.

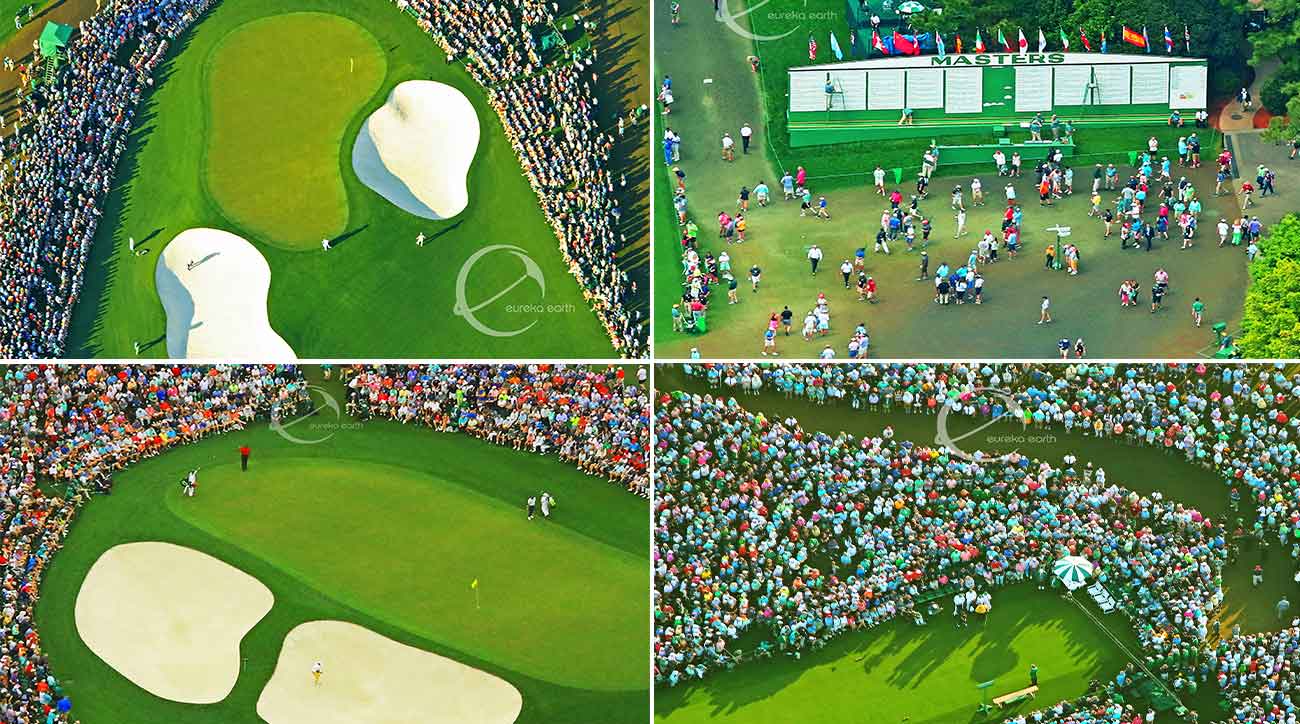

From 1,000 feet there are no guarantees that every — or any — photo will be a winner, so Dobbins’ strategy is to shoot as much as he can with the goal of capturing even a handful of arresting images. Of the 2019 Masters shoot, he said, “When you have overcast or darker conditions, you have to run a slower shutter speed, so to get a crisp shot is difficult.”

Dobbins came away with several standouts last year — the massive gallery awaiting Tiger around the 1st tee box, patrons relaxing under umbrellas by the clubhouse — but his piece de resistance was a snap of Tiger’s caddie, Joe LaCava, tossing a ball to his boss on the 9th green, the Bridgestone visible in mid-flight (see photo, above). “I had no idea I caught that one,” Dobbins said. “For the conditions we had, I was really happy with that. It’s hard enough to hold a camera still from an aircraft, let alone when it’s blowing 35.”

Dobbins sells large-format posters and canvases of the Woods-LaCava shot on his website, but his Masters business is only a lark. His primary quest remains providing America with a real-time bird’s-eye view of itself, and he’s hopeful his Masters coverage will help bring attention to the kind of images he’s capable of providing.

Dobbins isn’t a golfer, and even his unique vantage point of the last couple of Masters hasn’t inspired him to take up the game. “If I can’t be good at it, I don’t want to do it,” he said. “I have a tendency when I get into something to go full bore.”

To receive GOLF’s all-new newsletters, subscribe for free here.

ADVERTISEMENT