2024 Wyndham Championship: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

2024 Wyndham Championship: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

Can this woman save Detroit’s public golf courses from extinction?

Minutes later Peek was out on the course, tending to her duties as director of golf operations for the three munis: Rackham, Rouge Park and Chandler Park. She greeted a regular as he headed for the 1st tee, sent off members of a local Elks chapter as they commenced their weekly round, and checked in with groundskeeper Doug Melton and his affable dog, Baxter.

It hadn’t rained in three days, a welcome change amid the unseasonably wet weather. In Peek’s race against time, rain impedes progress. On an inclement day, Rackham might be lucky to have 20 players on its tee sheet.

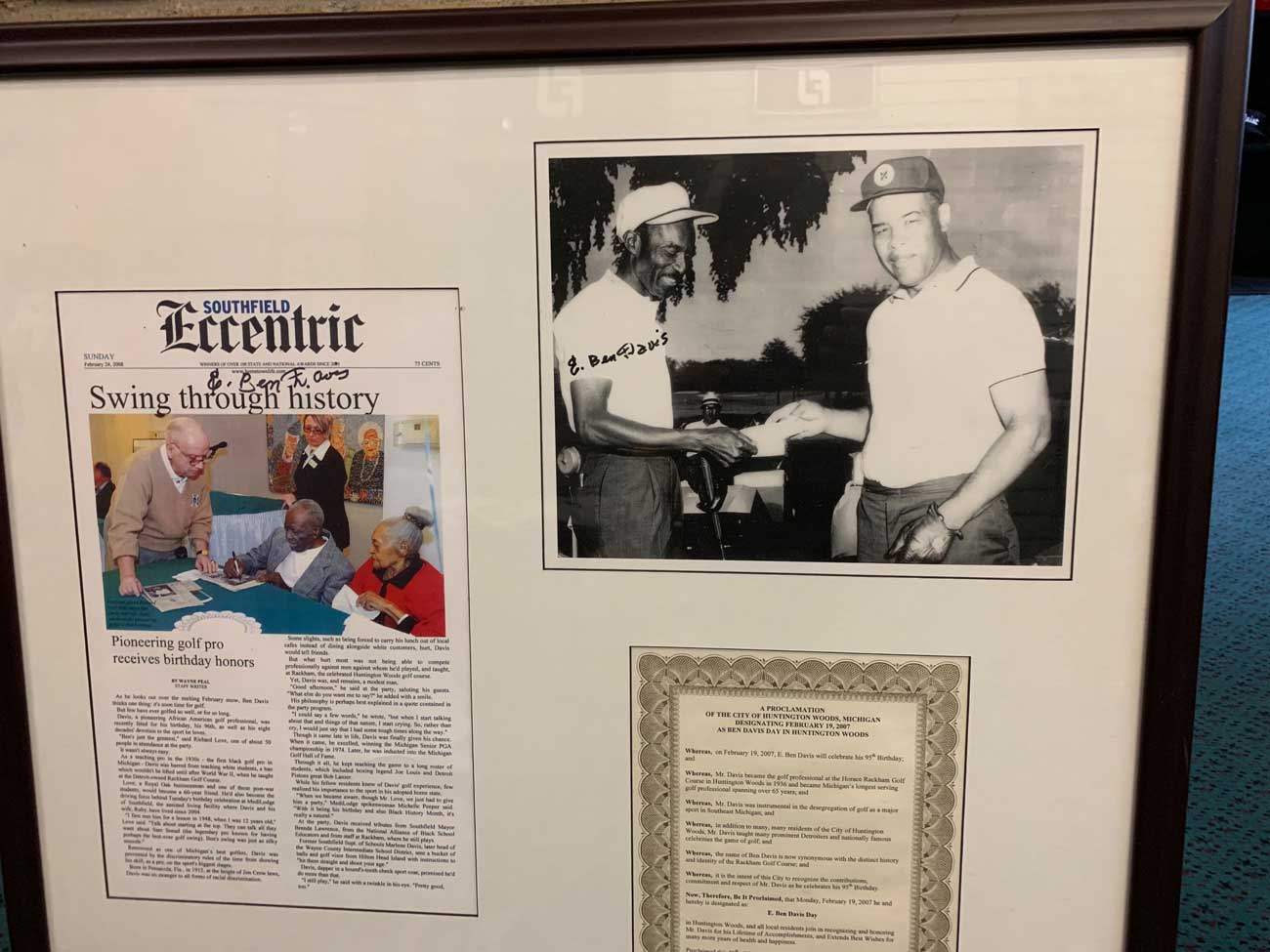

Rackham is six miles north of Detroit Golf Club, site of this week’s Rocket Mortgage Classic. It doesn’t get the attention that DGC does but it has rich history of its own, extending back to its opening in 1923. Ben Davis, the first black head pro at a municipal course in the U.S., taught there for 50 years. Among his students was famed boxer Joe Louis, a Rackham regular. The two would play money matches. In the 1940s, Louis hosted an annual golf tournament at Rackham, aimed at showcasing talented black players.

Rackham is also where Peek fell in love with the game. As a kid, she convinced her best friend to attend a youth golf clinic with her at the course. Volunteer pros — Davis among them — painted small circles on the 1st fairway and had the juniors swing their clubs back and forth for one carefree hour. Peek was hooked. She recounts excitedly slinging her golf bag over her shoulder and riding her bike down to the course.

Fifty years later, the details flow with a nostalgic yearn. The clinics were a staple in a vibrant golfing community. For Peek, they were the gateway to her livelihood.

All of which is to say, few can speak with the more authority about Detroit golf — its history, spirit, decline, heart — than Peek. She grew up on it. She lives it. She loves it.

Now, she’s trying to save it.

***

ADVERTISEMENT

The initial vote was 4-4. Everyone knew the fate of Detroit’s golf hung in the balance. The city council faced a dichotomous choice in March 2018: approve the hire of Signet Golf Associates to take over the operations of its three public golf courses or don’t. The latter option was as ominous as it sounds.

“There was an immediate conclusion that the alternative was ‘we’re going to close the golf courses,’ ” Peek said.

From 2011-18, total rounds played at Detroit’s four public courses decreased by 21 percent. From 2015-16, revenue dropped 22 percent. In 2018, the city closed Palmer Park golf course, leaving just three munis standing in a tenuous purgatory, wondering if they might be next. The city was blunt in its rationale.

“[Palmer Park] hasn’t made money in quite some time, and we didn’t think it was worth investing money into it,” Brad Dick, the director of Detroit’s General Services department, told CrainsDetroit at the time. “We’re post-bankruptcy and looking to be fiscally responsible.”

Slowly, the golf community came to the same fear: Was the game on the brink of extinction in the city?

Ray Custard — known by the regulars as “Sugar Ray” — is a superintendent at Rouge Park. He recalled tensions rising at the time.

If the courses closed, “them people would go crazy,” he said last week, pointing to a foursome meandering its way to the 5th tee box. “I’d start bowling. But I don’t like bowling.”

In 2017, the three remaining munis skirted that ill fate. A week after the deadlock, a tie-breaking ninth vote awarded Signet a two-year contract to take over management. Some called it a “bridge” contract. Cynics might say it was an ultimatum.

Peek refers to it as an “experiment” — and one she’s taken on with vigor. In some ways, her new job was a venture she never saw coming. In others, it’s a role she’s been building toward her whole life. Nearly four decades ago, Peek parlayed those youth clinics into private golf lessons, then three Q Schools. In 1983, she became the first black member of the Michigan LPGA, and became head professional at Rackham Golf Course. But when she left the golf industry in 2005, feeling her lifelong passion gradually dwindling, she figured it was for good.

Then Signet came calling.

“What an amazing opportunity this could be, to take this once again and just lead it in a direction of being vibrant,” Peek remembered thinking. “Seeing people stand in line on those tees, seeing people laughing and having fun, seeing those league groups out every day.”

Peek rushed to hire staff, lease golf carts, buy maintenance equipment. It was chaotic, but she loved every minute of it. Slowly, the upkeep of the courses began to improve — aerification of greens, verticutting, maintenance of the rough, consistency of the bunkers. Last May, the city invested a modest $2.5 million in capital improvements, helping Band-Aid over some of the more glaring issues. Without any long-term assurance, change has to come incrementally.

Peek’s mantra is simple: If each prospective golfer is welcomed with open arms, each staff member shares her passion, each day builds on the previous one, everything will work out for the best. Enough hard work and people will stream through the doors. Enough prayer and the rain will hold off. “Show your joy, and that will separate you from competitors,” she says.

“It might take a little more to get back, to get to that level. All I can hope is what the city sees is solid and substantive enough, that even if we fall a little short, they’ll still know we’re the ones for this,” she says, her voice building. “You’re not going to find better people. You’ll see people here who love what they do.”

Among those people, Peek says, is a local school teacher, who works in the pro shop twice a week.

“I guarantee you, I could take you to places today that you’d think you were interfering with their day by playing a round of golf,” Peek says. “Over here, you don’t get that sense at all. You get the sense that, ‘Yes, we want you — we desperately want you to be here — and we’re willing to do whatever it takes to have you here as well.’”

There are days Peek pulls into her spot at 5:30 a.m. to a half-filled parking lot. Those days give her hope. She thinks her courses are making progress, estimating a double-digit revenue increase and a nine percent increase in rounds played from 2018. It’s cause for hope. Now if only that damn rain would hold off.

Still, a vital decision looms. In February 2020, Signet will either be awarded a long-term lease or not.

Peek prefers to imagine a completed rejuvenation of these courses, a sustainable ecosystem of public golf. There are kids waiting to fall in love with the game, like she did. There are clinics to be run, leagues to be formed, future professionals to be bred. After a decade filled with pessimism, Peek offers her life’s tale as a vessel of optimism. She knows what golf has given her. She’s now doing everything to pay it back.

What would it mean to save Detroit golf?

That infectious smile returned as she sat back in her chair.

“A great way to finish,” she said. “It’d be a perfect No. 18 for me.”

ADVERTISEMENT