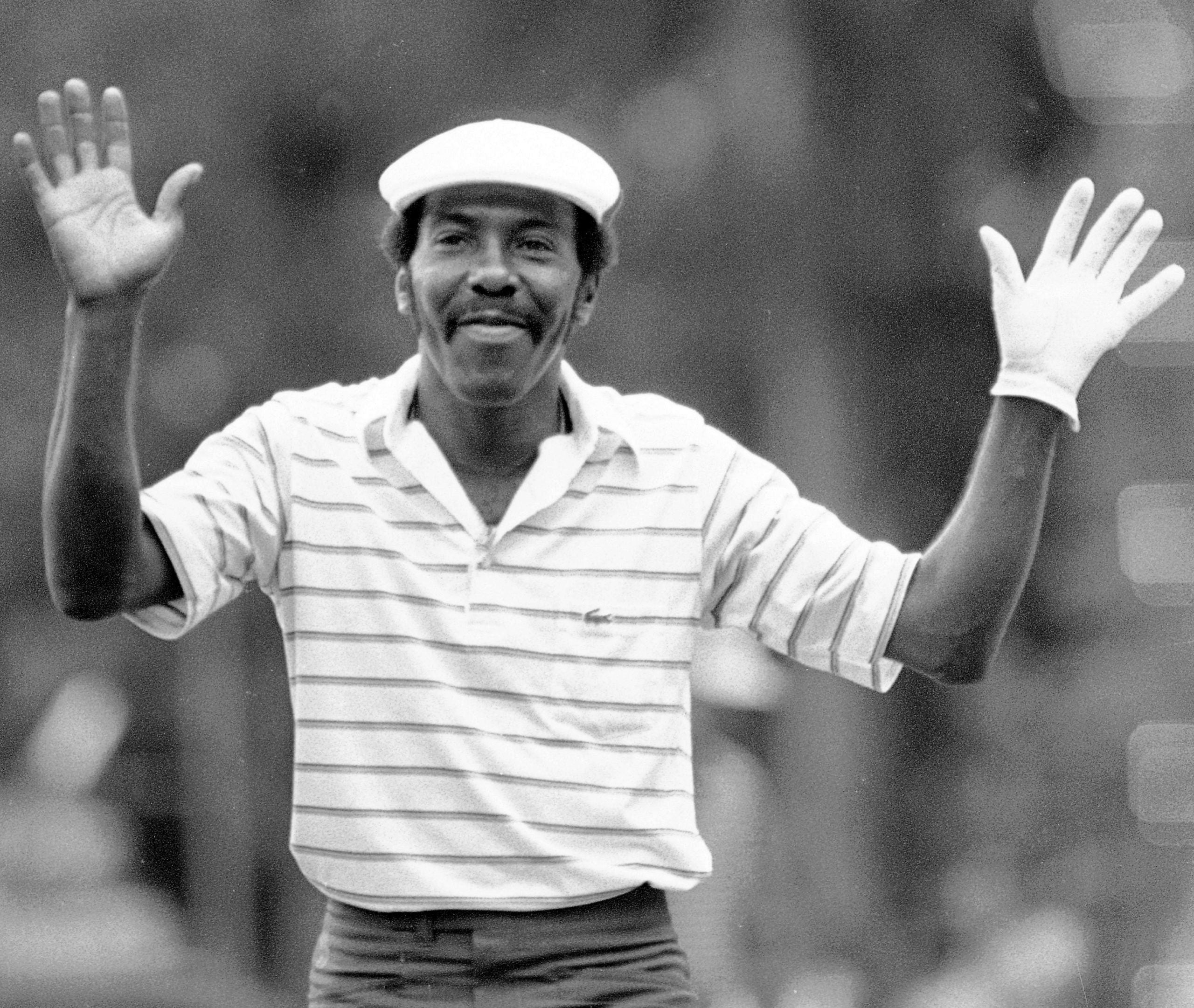

Calvin Peete did not get the attention he deserved, not in his life and not in his death, which came last week at age 71. Peete was a dark-skinned black man who was born in Detroit in 1943 and who did not pick up a golf club until friends dragged him to the game one summer day in Rochester in 1966. He became a daily presence at various South Florida public courses in the early ’70s, turned pro in his early 30s and was the winner of the 1985 Players Championship at the Stadium course, where the Tour lands this week. Some trip.

The man had to take a high-school equivalency test to meet the PGA of America’s qualifications when he made his first Ryder Cup team, in 1983. He won 12 times on Tour between 1979 and 1986 and did so with a left arm he could not straighten, owing to a broken bone that never healed properly. He was self-taught, self-styled and independently owned and operated. The Tour will not see his likes again.

Or will it?

When you look at the swings and the straight-and-narrow life stories of the winners of golf’s biggest events in recent years, the similarities are striking. Whether you’re talking about Adam Scott of Australia or Louis Oosthuizen of South Africa or Sergio Garcia of Spain or Rory McIlory of Northern Ireland or Jordan Spieth of the United States, the broad brushstrokes of their lives are essentially the same. They all were prodigies. They all had fathers with intense interests in their sporting welfare. They all had access to the best instruction, the best equipment, the best junior competition. Their swings were all picture-perfect as teenagers, or close to it. They all turned pro before they were old enough to drink — at least in this country.

But when you broaden the sample, and consider the sweep of humanity represented in professional golf today, you realize that in some significant measure Calvin Peete’s life example lives.

Consider some of these swings, and some of these life stories, among the players in the field this week at the Players. Angel Cabrera. K.J. Choi. Victor Dubuisson. Jim Furyk. Robert Garrigus. Bernhard Langer. Will Mackenzie. Sean O’Hair. Vijay Singh. Camilo Villegas. Bubba Watson. Boo Weekley. Willie Mac was one wrong turn from winding up in a Jon Krakauer book. Dubuisson’s life story is such a mystery you cannot be sure he knows it himself. Garrigus once dealt with drug issues. These are men for whom not everything in their lives fell their way. They are better for it, and professional golf is more interesting for it. The Players Championship is more interesting for it. John Daly lives.

The Miguel Angel Jimenez-Keegan Bradley altercation at the Match Play last week in San Francisco was unfortunate. It brought to mind something Tom Lehman said years ago at a Ryder Cup: “If we had to play match play every week, we’d be as bad as the tennis players.” But the undercurrent of their verbal altercation was not a rules dispute, but a territorial one. You take two feisty men, put them in a head-to-head competition and, on that day, all their worst impulses come out. Bradley felt his integrity — his manhood, really — being challenged by Jimenez’s hovering. You know what that tells us? Bradley is accustomed to standing up for himself, and Jimenez is too.

That may be contrary to the code of graciousness that is the hallmark of amateur golf, but standing up for one’s self is what the professional game is really all about. It’s not about imitating another person’s swing or manner or sound bites. It’s about figuring out — for yourself — the best way to get the ball in the hole as efficiently as possible. What we’re really talking about here is a nod to individualism. You don’t have to have led a hard-road life to have it. Jack Nicklaus was a country-club kid, and he had it. But a hardscrabble road helps. “I feel sorry for the rich kids now,” Ben Hogan once told Ken Venturi in a TV interview you can find on YouTube. “I really do. Because they’re never going to have the opportunity I had.” As a statement, it’s too broad. As an insight, it’s spellbinding.

It was a disappointment to read in Hank Haney’s book, The Big Miss, that Tiger Woods was so dependent on Haney (as Haney tells it) for tournament-day swing tips and pep talks and encouragement. The root of Hogan’s mystique is that he figured it out for himself. But you know who else did? Furyk, Cabrera, Singh, Watson. Furyk and Watson have swings that will defy Trackman analyses. PTL! It’s easy to point out the similarities in the swings and life stories of most of the successful Tour players. It’s the different ones — the different swing paths and life paths — that give the Tour what it craves and needs.

When Calvin Peete won the Players, Hale Irwin was his playing partner. Hale Irwin was not a warm and fuzzy man — you don’t win three U.S. Opens by being warm and fuzzy. But Irwin, who figured out the game for himself, knew he had just observed an odd and amazing thing: a self-taught man, from a background the likes of which the Tour had never seen before, winning one of the richest prizes in all of golf.

When it was over, Irwin placed his palm on Peete’s chest — on top of his heart, really. He understood the magnitude of the moment, and so did we. The Players is not just about the great big pile of cash you get for winning. (Peete got $162,000, or about $350,000 in today’s dollars; Martin Kaymer got $1.8 million last year.) It’s about what a player has to overcome. Not just over the four days, but the 25 or 30 years or whatever it might have taken to get there.

This article appeared in the most recent issue of SI Golf+ Digital, our weekly e-magazine. Click here to read this week’s issue and sign up for a free subscription.