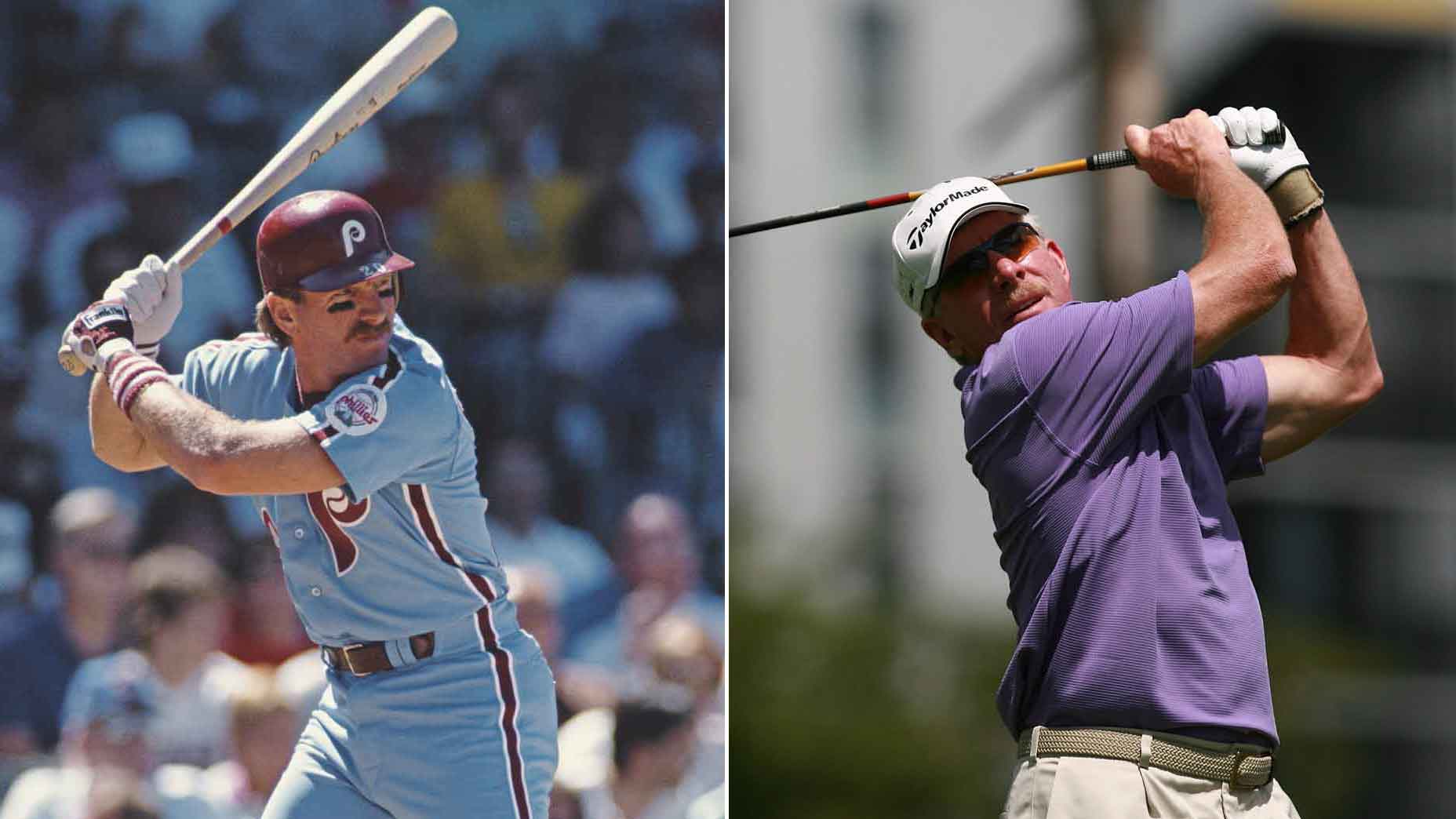

After the Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt voluntarily ended his 18-year baseball career in 1989, four months short of turning 40, he started thinking about a life in golf. With others, he developed an athletes-and-celebrity golf circuit. By his late 40s, he started devoting himself fulltime to golf, to see if he could get good enough to make it on the senior tour. He got very good. But not Bruce Fleisher-Allen Doyle-Bob Duval good.

There are layers and layers, in every sport. Looking back, he says, he spent too much of his practice time hitting full shots on the range, and not enough on the putting and chipping greens.

“If you keep doing what you’re doing, you’re going to keep getting what you’re getting,” Schmidt says in our latest GOLF Originals episode. He applies that phrase to every aspect of his life.

Schmidt and Tom Watson were both children of the Midwest who were born in September 1949. Schmidt hit 548 home runs without ever trying to hit a single one. He won the Gold Glove as the National League’s best defensive third basemen 10 times. He was, overwhelmingly, a first ballot Hall of Famer. When I suggest, in an hour-long interview that we struggled to edit down to 14 minutes, that he was to baseball what Lee Trevino was to golf, Schmidt said, “I see myself as Tom Watson.”

Fair enough. The joint membership in the class of ’49. Their shared heartland (Kansas for Watson, Ohio for Schmidt) childhoods. Their stoic demeanors. Also, their impatience with false modesty.

When I asked Schmidt if he could have helped Michael Jordan with his hitting, in Jordan’s brief sojourn in the bushes of minor-league baseball, he was certain of it. “I could teach him to hit,” Schmidt said. Note the present tense, like it’s not too late. Schmidt, like Watson, did not lack for confidence. MJ, the same.

I got to watch Schmidt’s entire baseball career unfold and I saw him play golf when he was a 70-shooter. Same guy, really. His approach to both sports was methodical and cerebral. But something he said in our Golf Originals interview really caught me by surprise. He talked about how, in baseball and in golf, he was consumed by “mechanics, worry, fear of failure.” And when he said that, the player who came to mind for me was . . . Tiger Woods.

Woods has never gone deep into his state of mind as an athlete. Maybe, when he’s Schmidt’s age, he will. There are obvious external similarities between the two men. Schmidt, walking to the plate, standing by third base, was never one to fidget, to waste energy, to let himself get distracted. One of the most memorable moments of the 2019 Masters, from my vantage point, came on Sunday on 17, when Woods was waiting in the fairway watching as Brooks Koepka, Ian Poulter and Webb Simpson putt out. Woods just stood at his bag, his hands on it, barely moving for several long minutes, lost in thought.

But I have also thought, watching Woods closely through his career, that there have been many times when he was filled with worry, confused about his mechanics, afraid that he might fail. I felt like you could see it in his face, and sometimes in his shots. I think Schmidt actually identified three of the things that kept Woods on the practice tee for so long, why he punished himself in the gym, why he almost never relaxed on the golf course. A constant wrestling match with mechanics, some deep and motivating level of insecurity.

David Feherty on life, loss and his new gig at LIV Golf | GOLF OriginalsBy: Michael Bamberger

It’s amazing how often, in major championships, Woods would have a near-perfect pre-round warmup session, with Butch Harmon or Hank Haney at his side, and then hit an opening drive off the first that went crazily left of wildly right. Woods would figure it out quickly enough. The greats do. But there were moments he could not handle. Way better to have it on the first hole than the last.

If you play golf with Schmidt, and you see him making a slow, purposeful walk from cart to green, putter in hand, it’s hard not to think of the thousands of times he made slow, purposeful walks from the on-deck circle to the batter’s box, bat in hand. He’d have the pitcher in mind then. He has the putt in mind now. Maybe not now now, but certainly when he was playing competitive golf in Florida tournaments and on the celebrity circuit. Woods did the same thing. He walked with purpose.

Woods had, as a younger man, a perfect physique for golf, so strong through the core, but also so limber. Schmidt, for baseball, did, too, a chest that could stop wicked hops when he patrolled third, fast-twitch legs when scoring from second, arm strength and speed that allowed him to hit 400-foot line-drive home runs and throw cross-field bullets from his knees. The late Pete Rose once said of Schmidt, “To have his body, I’d trade him mine and my wife’s, and I’d throw in some cash.”

But what I get from our interview with Mike Schmidt, and what you might get from watching it, more than anything, is how his head was in everything he did.

I asked Schmidt if a career in golf would have been as satisfying for him as his career in baseball. He didn’t hesitate: Yes. He thought it would be harder to do in golf, to enter the pantheon, as he did in baseball. Still, he would have done it.

“I would have figured it out,” he said.

His smile masked nothing. He meant it. The true greats mean business.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com.