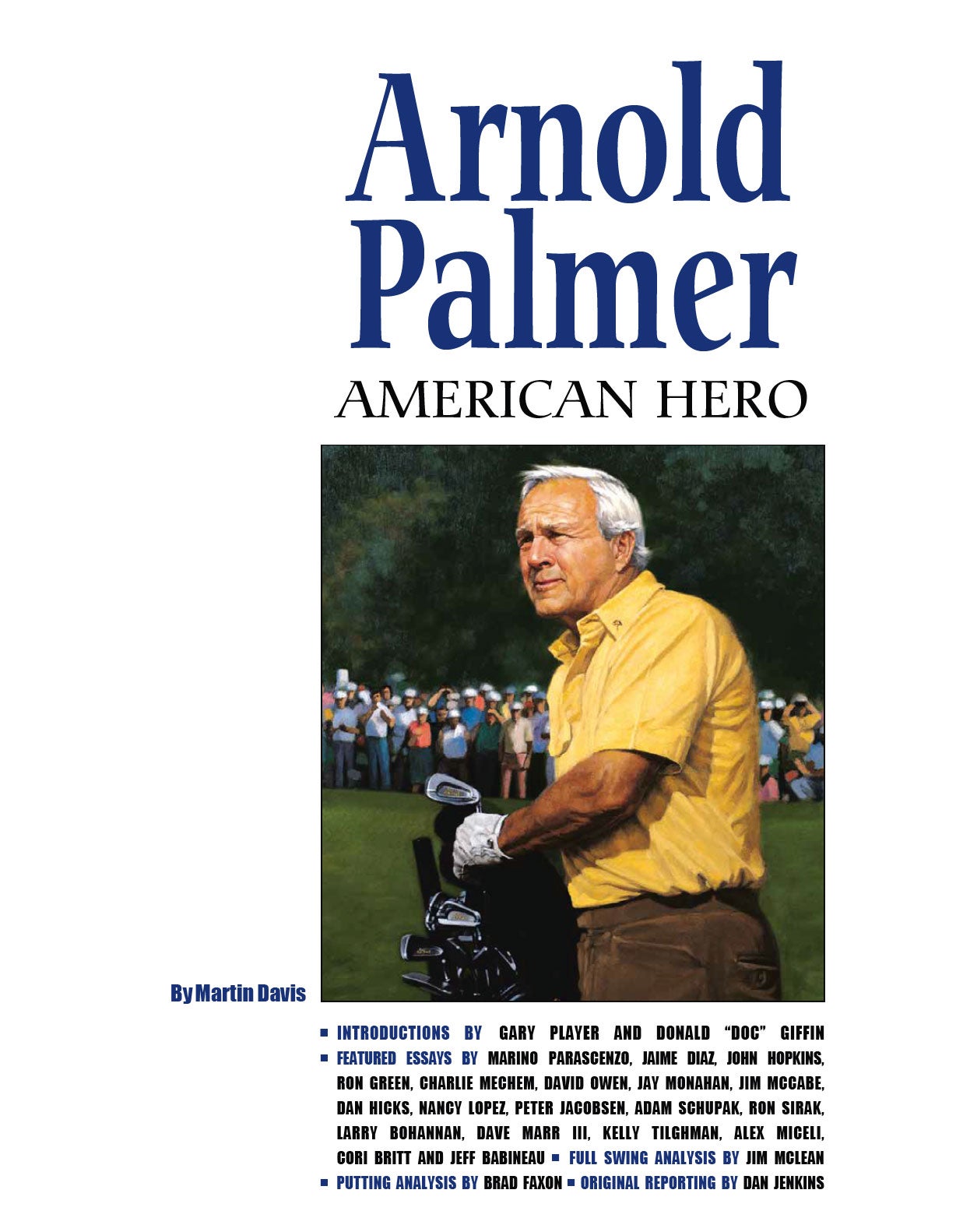

The following passage was excerpted with permission from “Arnold Palmer: American Hero,” © 2022 The American Golfer, Inc. You may buy the book here.

***

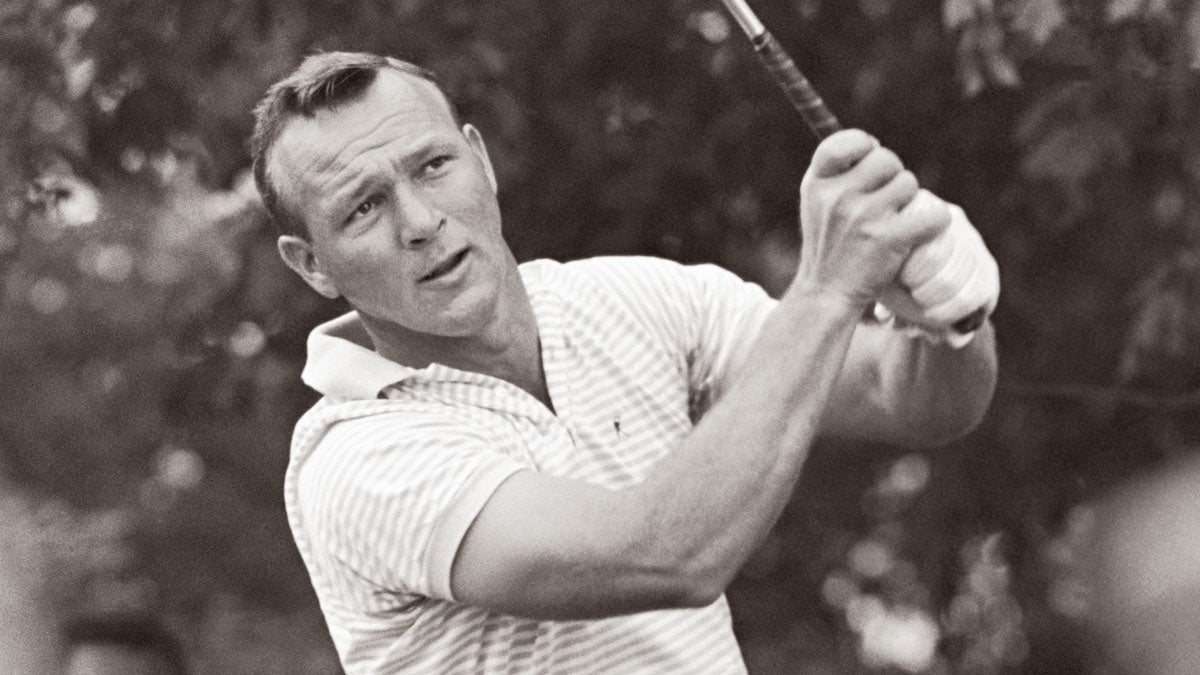

Golf is not a game of perfect, except for one thing: Arnold Palmer’s grip.

In the moments before starting his backswing, the way Palmer’s hands held a club checked every box in an instruction textbook. The respective Vs on each hand formed by the crease between thumb and forefinger pointed at the shirt seam on the right shoulder. The lifeline of the right hand folded over and covered the length of the left thumb. The right thumb pressed securely but gently against the wrapped leather.

The only more famous fastening belonged to Harry Vardon, whose eponymous interlocking grip was the one Deacon Palmer chose for his then 4-year-old son. After placing little Arnold’s hands together on a cutoff 3-wood exactly so, the father said, “Boy, don’t you ever forget that or change it.”

Arnold didn’t, and his grip became the vital control clamp for a violent swing in which an explosive release in the hitting area was followed by an equally forceful hold-off of hand rotation, the reason for Palmer’s trademark helicopter finish.

But ultimately, functionality wasn’t what set the Palmer grip apart. For all the dogma about the correct way for the hands to tie together, a close study of the world’s best players through time proves their grips have been nearly as individual and varied as their swings.

No, what mattered most about Palmer’s grip was how — yes, perfect — it looked. His hands — strong and meaty, but not so large as to be encumbering — simply fit with a satisfying sense of sealed unity, knitted together as neatly as the weave in one of Palmer’s vintage alpaca sweaters.

For all the obvious power in his hands, they also possessed a world of feel and touch, as he showed with the equally aesthetically pleasing reverse overlap grip he used when putting.

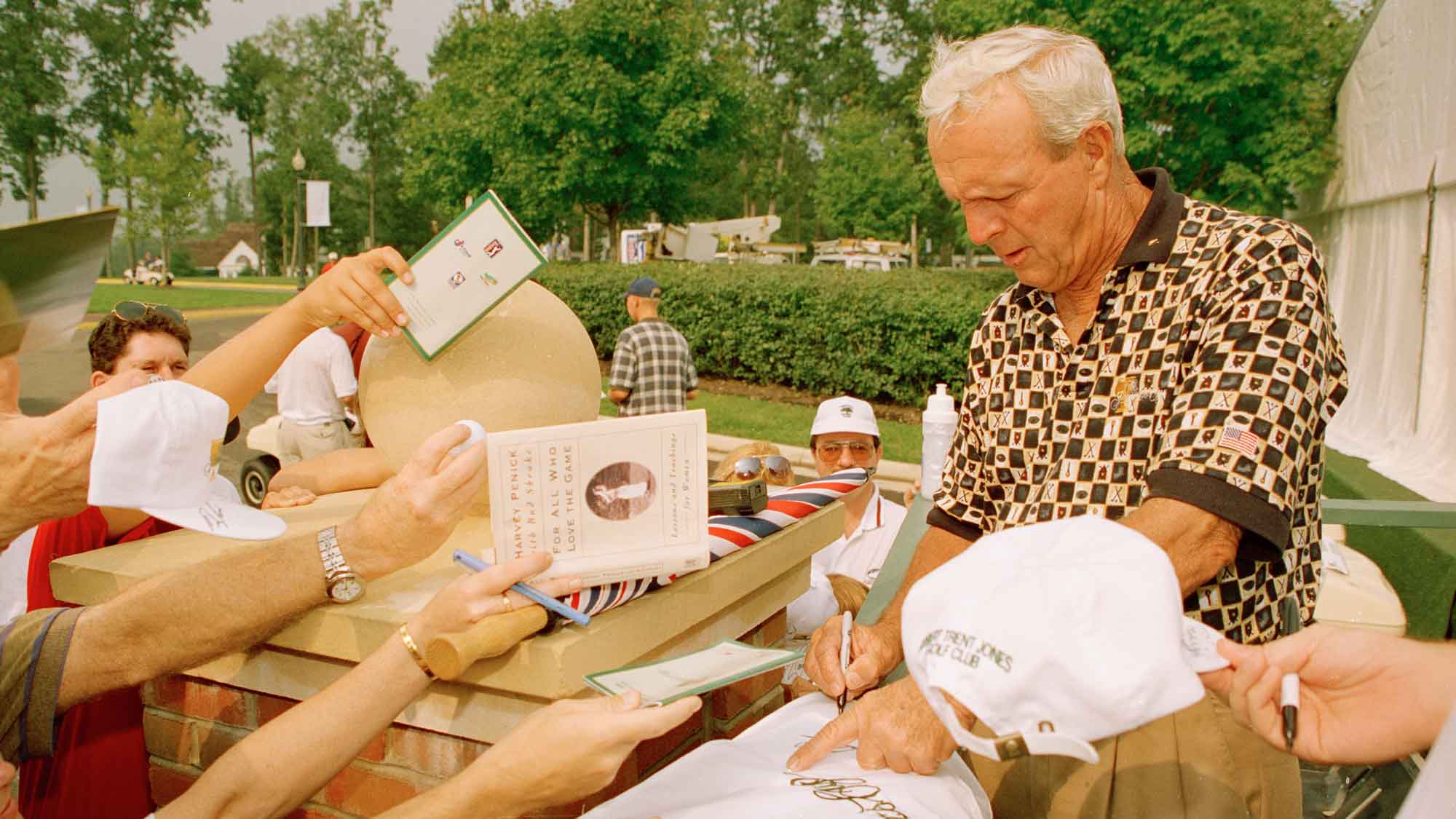

Both qualities were immediately evident in Palmer’s handshake. For those lucky enough to have felt it, the size, strength and ruggedness were unmistakable, but so also were warmth and sensitivity.

Hands you could count on, evocative of the man himself. The hands of a hero.