Compared to his contemporaries, A.W. Tillinghast wasn’t as prolific as Donald Ross, nor as traveled as Alister MacKenzie, nor was he the father of American golf course design, a claim that C.B. Macdonald could make. Nevertheless, for sheer design excellence among the Golden Age greats, Albert Warren Tillinghast takes a backseat to no one. “Tilly the Terror,” as he was known, is the sixth architect to be inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in the Lifetime Achievement category, following Ross (1977), Robert Trent Jones (1987), MacKenzie (2005), Macdonald (2007) and Pete Dye (2008). Here’s what you need to know about one of history’s most underrated architects.

Top 10 Courses

Source: GOLF Magazine 2013-’14 Top 100 Courses in the U.S.

Winged Foot (West), Mamaroneck, N.Y.; ranking: 13

San Francisco Golf Club, San Francisco, Calif.; ranking: 18

Bethpage (Black), Farmingdale, N.Y.; ranking: 23

Baltusrol (Lower), Springfield, N.J.; ranking: 29

Quaker Ridge, Scarsdale, N.Y.; ranking: 39

Somerset Hills, Bernardsville, N.J.; ranking: 41

Winged Foot (East), Mamaroneck, N.Y.; ranking: 47

Baltusrol (Upper), Springfield, N.J.; ranking: 60

Ridgewood, Paramus, N.J.; ranking: 84

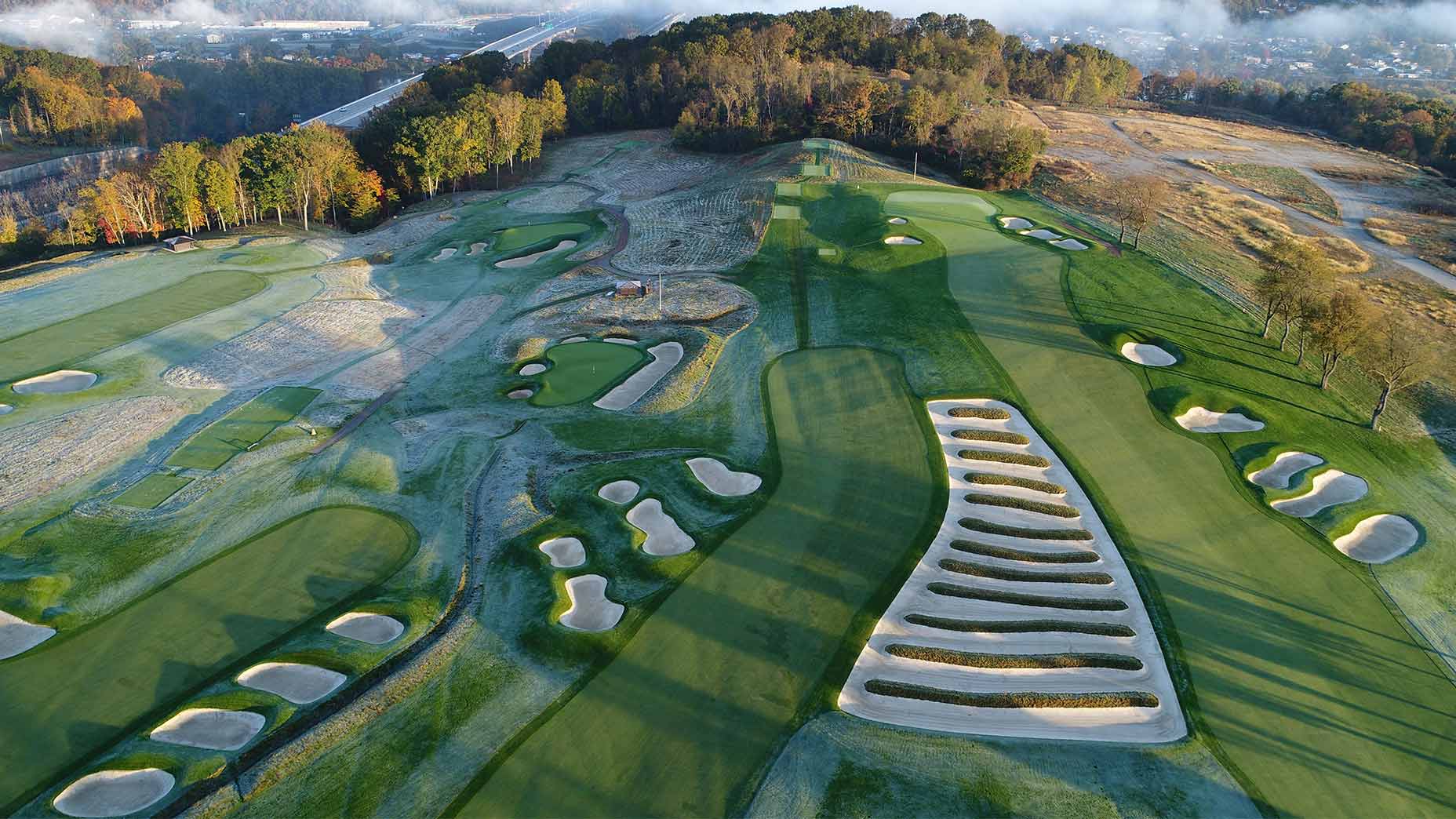

Baltimore Country Club (Five Farms East), Timonium, Md.; ranking: 94

Design Philosophy

Tillinghast felt that a course’s collection of par-3s was indicative of its quality. “The character of the one-shot or par-3 holes has more to do in checking the assault of the 70-breakers than any other factor,” he wrote. “The course stands or falls through the character of its one-shot holes.”

He acknowledged, however, that while the par-3s were a foundational element of design excellence, strategy and shot placement were paramount: “The relationship between the properly placed shot to the fairway and the following one to the green is the real standard of measuring the merit of any course. I think that I will always adhere to my old theory that a controlled shot to a closely guarded green is the surest test of any man’s game.”

Tillinghast maintained that golf should be fun for everybody. He espoused that the best way to balance the enjoyment factor for the average Joe with the challenge preferred by a low handicap golfer was via variety and interest on and around the greens, especially though imaginative green contouring. As Tillinghast surveyed his just-completed 36 holes at Winged Foot, he related this aspect of his design philosophy:

“As the various holes came to life, they were of a sturdy breed. The contouring of the greens places a premium on the placement of the drives, but never is there the necessity of facing a prodigious carry of the sink-or-swim sort. It is only the knowledge that the next shot must be played with rifle accuracy that brings the realization that the drive must be placed. The holes are like men, all rather similar from foot to neck, but with the greens showing the same varying characters of human faces. The presence of an old-fashioned featureless green would be just as much out of place on an up-to-date course as cobble-stone paving along Fifth Avenue … If the greens themselves do not stand forth impressively the course itself can never be notable.”

Tillinghast preferred the natural over the artificial. He appreciated aesthetic wows, but not where they were forced.

“A round of golf should present 18 inspirations — not necessarily thrills, because spectacular holes may be sadly overdone. Every hole may be constructed to provide charm without being obtrusive with it. When I speak of a hole being inspiring, it is not intended to imply that the visitor is to be subject to attacks of hysteria on every teeing ground.”

Though he was a superb golfer, he understood that the appeal in design should not be based on distance and difficulty, but rather on options and strategic choices. “The merit of any hole is not judged by its length but rather by its interest and its variety as elective play is apparent. It isn’t how far but how good!”

Up Close & Personal

Tillinghast was an excellent golfer. He competed in three U.S. Amateurs between 1905 and 1912, losing in match play to once and future champions Walter Travis, H. Chandler Egan and Chick Evans. He finished 25th in the 1910 U.S. Open, played at Philadelphia Cricket Club, where he was a member. In 1922, he would design the new course for his home club, at the club’s Flourtown facility, a course now known as Wissahickon.

Born a fortunate son to a prosperous Philadelphia rubber-making family, “Tillie,” as friends called him, first journeyed to St. Andrews in 1896, making the acquaintance of Old Tom Morris and even playing the Old Course with him.

He claimed to have been present for the invention of the term “birdie,” and took credit for popularizing it. During a casual gang-style round at Atlantic City Country Club on the Jersey Shore in 1903, one player in his party of 12 or so smacked a low, long second shot onto the green of a par-5 and another player exclaimed, “That’s a bird!”

One of the earliest successful golf writers, Tillinghast wrote a syndicated newspaper column before World War I and contributed to Golf Illustrated magazine, becoming its editor in 1933. He published rankings of the top 12 professionals, male amateurs and female amateurs, scoring a prescient coup in 1916, when he named 14-year-old Bobby Jones as the year’s 12th-ranked amateur.

A classic Roaring 20s high-living character, Tillinghast made more than $1 million as a designer-builder, but lost it not only to the onset of the Depression, but also because he was a prodigious drinker, spender and investor in failed Broadway shows.

To earn some much-needed cash in the mid-1930s, Tillie went to work for the PGA of America, traveling around the country to member facilities and advising them of course changes and maintenance alterations as money-saving measures.

By the late 1930s, Tillinghast has relocated to Southern California, where he opened an antiques shop in Beverly Hills. By 1941, heart disease and other medical issues had taken their toll. That year, he moved in with oldest daughter Marion at her Toledo, Ohio home and passed away there on May 19, 1942.

For more news that golfers everywhere are talking about, follow @golf_com on Twitter, like us on Facebook, and subscribe to our YouTube video channel.