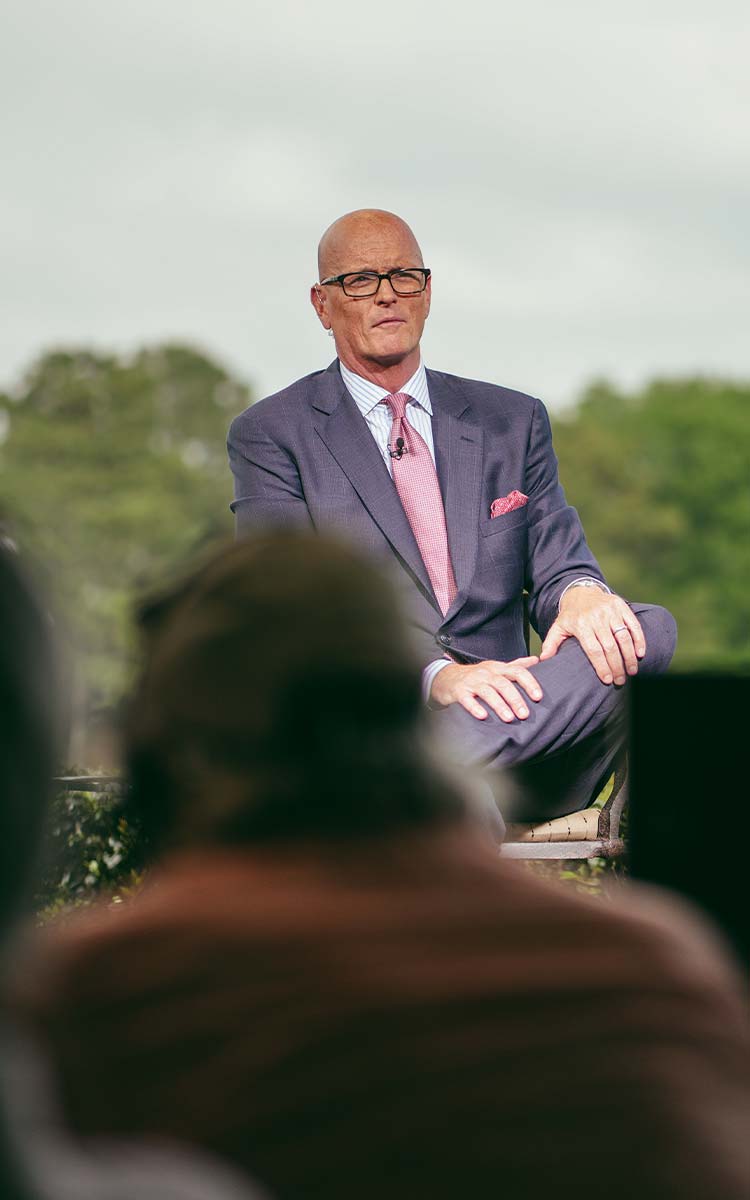

SCOTT VAN PELT ISN’T YOUR FRIEND.

But he sure feels like he could be. This is perhaps why, unlike the dozens of other famous people who can survive for days around Augusta National in reverential anonymity, he spends most of Masters week swarmed.

Consider the scene around Van Pelt near the practice range on Tuesday morning. The mob isn’t quite Beatlemania, but it runs five deep … and it’s multiplying every few seconds as the noise grows louder.

“Scott!!”

“SVP!”

“We LOVE you, man!”

Perhaps Van Pelt would be less noticeable were he easier to miss. At a wiry six-foot-six, he protrudes from the top of the frenzy with ease, the crown of his bald head visible above even the tallest well-wisher. He moves through the people like a toddler wading through the ocean — arms flailing, head bobbing, fists out to touch knuckles with the crowd. His slow, intentional strides begin to pick up as he senses the crescendo building. Still, his efforts at an easy exit are mostly useless.

“I just don’t blend in,” he says. “I think it’s the suit.”

His uniform is only part of the problem. The other is that, for all his many talents, Van Pelt is dreadful at saying no.

“Yesterday I ended up taking pictures to the point that I said, ‘I’m not Santa,'” he says with a laugh.

He’s right. At Augusta National, he might be more popular.

SOMEWHERE IN HIS DNA, Scott Van Pelt’s two dominant traits are still at war.

One is the class clown; the kid with grades so bad he was rejected from the University of Maryland’s journalism school. (His beloved alma mater has since rectified that oversight by welcoming him back as a commencement speaker.) The other is the underdog; the dude who needed an unusually lucky break to make it in sports media, then spent his first years in the industry grinding for a network that few people knew or cared about. Today, those divergent genes fill both halves of Van Pelt’s on-air presence — at once strikingly casual and neurotically well-researched — but it’s easy to forget they nearly kept him out of sports media altogether.

It took Van Pelt close to a decade after graduation to land his first true TV job, a product of both his college transcript and deep roots back home in Maryland, where he’d lost his father when he was still in college. In those early years, his life oscillated between work as a DC TV station intern and mortgage banking. But television kept calling to him, so he kept looking for a break. A few months later, one finally came. An old friend called him with an opportunity at a brand-new, 24-hour sports network called “Golf Channel.” The network was niche, but it already had a name and the backing of a group of investors including Arnold Palmer. Van Pelt was sold.

In hindsight, the move to Orlando was more melancholy than he first realized. Sure, he’d landed his dream job at a nationally televised sports network, but he was pretty sure he hadn’t earned it.

“It’s the imposter syndrome, right?” he says now. “I couldn’t get into journalism school. I had horrendous grades. I wasn’t trained in anything. I was just a guy who was winging it — and I still am, to a degree.”

But if he was unprepared for the opportunity, nobody knew it. Van Pelt quickly ascended up the ranks, anchoring the network’s flagship show “Golf Central.” Before long, he was one of Golf Channel’s most prominent early voices.

“It was never doubt that I couldn’t do it,” Van Pelt says. “It was disbelief that any of this is.”

At Golf Channel, he grew to embrace the underdog role — and the disadvantages that came with it. On one occasion, he drove five hours from Orlando to Doral solely to ask Tiger Woods for an interview the following week. When the next week rolled around, Tiger requested the PGA Tour make Van Pelt his first interview.

“We were supposed to have 15 minutes,” he says now. “We spoke for 45.”

Determination proved a key constellation in those early days, even as his image was on the rise. Exhaustion was acceptable, he realized. Failure was not.

“I vividly remember showing up to the Open Championship in 2000. It’s me and a shooter, and ESPN has this army,” he said. “I’m like, this is like fighting a tank with a popsicle stick. But f— it, let’s fight, because we’ll get what we need.”

Today, he keeps a post-it note on his desk from the end of his time at Golf Channel, remnants of a $100 bet he lost with a producer. It reads: I’ll never work at ESPN.

At the time, Van Pelt thought he was being cheeky. Now he knows it was something much deeper than that.

“The real reason I said that … I think it was protecting myself,” he says now. “In my mind, I was thinking, ‘Why would they hire me? I wouldn’t.'”

THERE IS A STRANGE THING that happens to Scott Van Pelt once the ESPN cameras turn off: he’s still Scott Van Pelt.

TV stardom has a peculiar effect on most people. Some personalities shunt inward when the lights go dark, their outer extrovert peeling away an inner introvert. Others are emboldened by the authority that joins the work, their egos inflated and self-image emboldened.

Oddly, Van Pelt is neither of these things. In quiet moments, he speaks in the same eloquent soliloquies, his voice rising and falling with the same intonation. He makes the same jokes. His eyebrows raise from under the bold frames of his brown glasses with the same vigor. About the only change is the occasional swear — a “bad” habit he says spawned his only rule of being on television.

“No cussing.”

At first, there’s something about his normal self that feels performative, like he doesn’t realize the cameras are off. But his friends describe a different reality. He isn’t playing the character you see on TV, he is the character.

“Working with him, it never feels like work,” says his Masters co-pilot, two-time major-winner Andy North. “It’s just two guys sitting there talking about stuff they enjoy talking about. I mean, we truly have so much fun. That’s a really rare quality.”

Van Pelt keeps a close circle. He has been working with North for the better part of his 23 years at ESPN. The same is the case with most of his production staff, including longtime friend/segment producer/gambling commentator “Stanford Steve” and ESPN VP of production Mike McQuade.

A few years ago, when Van Pelt received the green light to film his new midnight SportsCenter with SVP back home in Washington, DC, he brought most of his old production team with him. If they weren’t like family before, they certainly are now. On Masters Tuesday, a question about the team yields three-sentence bios about half of them, from McQuade to junior producer Maddie Brightman.

“Maddie’s a Penn Stater,” he says of Brightman. “She has such a great perspective on sports, and it helps that she’s young. I’m a middle-aged dude. I’m too old to know what’s interesting.”

He is not too old, evidently, to know what’s good. Today, he is the most-watched late night show in sports TV, averaging more than 900,000 nightly viewers. His “One Big Thing” segments — a show-closing, direct-to-camera essay — regularly attract millions of views and, in the case of his beloved dog Otis, the whole world’s adulation.

“In the history of me doing anything, nothing has ever connected with people like me talking about my dog,” he says. “One Big Thing was the perfect landing spot for that.”

More recently, even his failures have become a source of praise. In late March, Van Pelt was in the middle of the midnight SportsCenter when his voice suddenly quit on him. Every sentence was a struggle, and most of the show was near inaudible. He braced as he checked his Twitter mentions when the show went off the air at 1, but was stunned to find it filled instead with fans rooting for him to finish the show.

“You have to become really comfortable with the fact I think you might screw up, but when you do, the people become your net,” he says. “People really called my performance ‘heroic.’ I’m like, ‘Garbage. That was terrible.‘ But for whatever reason, I’m lucky to have people who are rooting for me.”

Much of Van Pelt’s success can be traced back to the authenticity of his message. Most people wouldn’t be able to summon the ability to care this much, but nobody can fathom him doing it any other way.

“Maybe 10 years ago, ESPN surprised me with a Fathers Day tribute video at the U.S. Open,” North says. “By the time we got halfway through the thing, we’re both crying on set. Scott and I, like two little kids.”

“That’s Scott. The people he cares about, he cares so deeply. He’d do anything for them.”

EVENTUALLY, VAN PELT PAID THE $100. But he kept the post-it, a reminder of the dangers of self-placed limitations.

It would be strange for him to start thinking rationally now. On Thursday and Friday morning, a quarter-century after he first fell into the Golf Channel gig, Van Pelt will call the first two rounds of the Masters on ESPN. This year, he will also host his own preview show, Welcome to the Masters, for the first time.

It’s clear he’s not kidding when he says Masters week is still very cool for him. Over the years, this week has become a way of watching the world change. Sometimes, like when he sees the galleries, it’s also become a way of watching his world change. Should the Masters ever stop being this cool, maybe some of the other stuff will too. But that’s a conversation for another day.

“No, burden is not the right word, it’s a blessing,” Van Pelt said. “When you belong to a public that you don’t know in a way where they care about your dog, and they are rooting for you to make it to 1 a.m. without a voice, and you feel they like you? Nothing about that’s a burden. It’s such a blessing.”

It seems the real lesson in Van Pelt’s story has very little to do with celebrity. He’s never felt like one anyway.

“If all you ever have to say is what you think, then you don’t ever have to remember your lines,” he says. “And if all you ever are is who you are, then you don’t ever have to put on your own outfit for the show. Then, after the fact, you’ll find people are kinda rooting for you somehow.”

SCOTT VAN PELT CAN ALREADY TELL YOU the best part of Masters week. It’ll come in the 18th tower at Augusta National around 2:50 p.m. local time on Thursday. Van Pelt will be alone then. Or, mostly alone.

It’s become a tradition of Scott’s to spend the last quiet part of Masters week in the company of a friend: his dad, Sam. It’s been 35 years since Scott and Sam Van Pelt’s final in-person conversation, but every spring, they spend a few moments together here at Augusta. This, Van Pelt admits, is the reason he keeps coming back.

“I just take a second and say, ‘I think you would have really gotten a kick out of this. I hope I’ve made you proud,'” he says, his voice cracking ever so slightly.

Ten minutes after Sam leaves his son, it’ll come time for Scott to do his job again. The cameras will whir to life and the producers will chirp and soon the rest of us will join Scott Van Pelt in the booth at the Masters.

It’s been a while since we’ve heard from him in this setting, but it won’t feel like it.

That’s how it goes with old friends.