I have never let the fact that I am mediocre at something stop me from doing it. For instance, golf. Right now, it is winter where I live, but a part of me cannot wait until the snow retreats from the local fairways. This is odd: I’m an adrenaline-sports guy, not a golf guy. Except for the fact that, to my surprise, I kind of love it. Finally.

It runs in the family. My great-grandfather painted his golf balls red so he could play through the Chicago winters. A cousin had been an LPGA pro in the 1950s.

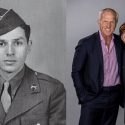

And my father grew up caddying and playing at a small-town country club outside Chicago. He must have had some talent, because he won the Illinois state high school championship as a junior. Big Ten schools came calling with scholarships, kindling dreams of a possible professional career. But he turned them down and went to college in the East instead.

After graduating, he didn’t play for more than 25 years. He lived in New York City, and his job left him no time for the game. But then, just before he turned 50, a business friend invited him to play at his club outside Edinburgh. He shot an eight on the first hole, but birdied the ninth. He was hooked. Before long, he was taking trips to Scotland and Ireland with his new friends.

I had taken golf for PE in college, mainly because it seemed easy. From the coach of the golf team, I learned many of the basics of a solid golf swing — but, unfortunately, not all the basics. More than once, at a driving range, I sliced the ball so hard that it thwacked viciously into a neighboring stall. Luckily, no one was hurt. From that point on my game had one goal: Not to injure bystanders.

One day I joined my dad to hit balls at the Chelsea Piers range in Manhattan. He cranked his first drive into the far nets, and the much-younger guy next to us turned and said, “Nice move!” These range outings became a regular thing, and I learned to love the (rare) effortless feeling of a cleanly struck ball. It’s as if you’re hitting nothing. That led to the occasional round on an actual course, a more intimidating prospect. I would tell my non-golfing siblings, half-joking, that I was “taking one for the team.”

So was my dad. Sometimes he would visibly wince as I ripped balls into the trees, lakes and underbrush. I could land a drive on the fairway, just not the correct fairway. I desecrated storied courses like Muirfield and Royal Dornoch in Scotland, the Chicago Golf Club, and Shawnee-on-Delaware.

Dad turned out to be a surprisingly patient teacher. He’d never been the kind of guy to do stuff like throw the football around in the backyard. My parents split up before I turned 10. Now, on the golf course, he got to play the role of nurturing dad/coach. His mantra was “Let your arms relax. Make them like ropes. Stop trying to hit it.”

I proved to be a slow learner, but I refused to give up. Arms like ropes. Stop trying to hit the ball. I stuck with it, chasing that perfect, effortless shot. But I also realized I was witnessing something special: My father had played this difficult game at a high level, and he was slowly reclaiming his mastery of it. He’s an old-school, Scottish-style player who loves the history and traditions of the game. My dad would rather die on the fairway and be devoured by groundhogs than ride in a cart. I admired that.

Gradually, imperceptibly, I got better. Dad gave me a copy of Golf in the Kingdom, and I learned to appreciate the Zen aspects of the game.

The fact that I began practicing yoga a couple of years ago helped me with breathing and staying grounded and balanced. Then something clicked. Suddenly, the ball flew straight(ish) more often than not. On the advice of an old Scottish caddie, I rarely keep score; I prefer to appreciate the good shots and forget the bad. But I am no longer the threat I once was to pedestrians.

Last year, my father and I went to play a few holes at his club. He had moved back to the Chicago area, in part because he’d reconnected with his best friend from college over their shared love of the game. The friend recently died of a terrible neurodegenerative condition, and a few months after his death Dad surreptitiously scattered some of his ashes on his friend’s favorite green. His tee shot on the next hole rolled straight into the cup.

On this day, after a bit of a shanky start, I was finding my groove. “The sweetest steps in golf,” my dad said, pointing me up the fairway to where my ball had landed, “are the ones past your opponent’s drive.” A few holes later, we stepped up to a tricky par 3 with the green set on an imposing bluff. I swung and felt … nothing. The good kind of nothing.

The ball soared before falling to earth. We watched it bounce on the edge of the green and roll out, coming to rest two feet from the pin. A near perfect shot. I’ve never seen my father happier.

Bill Gifford is the author of the New York Times bestseller Spring Chicken. He lives in Park City, Utah.