Twenty years ago, Tim O’Neal seemed primed to be the next great black player on the PGA Tour. He was 26 at the time, a Georgia State Amateur champion and a graduate of Jackson (Miss.) State University, where he had won 16 tournaments. That summer, during a charity outing at the Valhalla Golf Club in Louisville, Ky., O’Neal was paired with the late Charlie Sifford, who in 1961 became the first black member of the PGA Tour. When Sifford was O’Neal’s age, he was barred from membership on the PGA Tour due to the PGA of America’s Caucasians-only clause. Instead he started his pro career on the all-black United Golf Association tour.

Sifford had lived long enough to see black players denied access to tournaments and hear them called the n-word on the golf course. Toward the end of his life he witnessed the ascent of Tiger Woods. With his signature cigar dangling from his mouth, Sifford represented for O’Neal a bridge to the past and proof of a generation of talented black players who never had a chance to compete at the highest levels of the game.

“Charlie hit it really good,” O’Neal said. “He was extremely consistent. That was the thing that stood out. You could tell that he played the tour because of the way he played.”

This week, O’Neal, 46, is in the field at the Genesis Open as the recipient of the Charlie Sifford Memorial Exemption, which was introduced in 2009 to promote the advancement of diversity in the game. O’Neal’s appearance at Riviera will mark his seventh PGA Tour start but his first since 2015 when he made it through sectional qualifying to earn a spot in the U.S. Open at Chambers Bay, where he missed the cut. O’Neal has won tournaments all over the world and twice came within a shot of securing his PGA Tour card at Q School. But his Tour dreams never materialized.

“It just hasn’t worked out the way I wanted it to,” O’Neal said. “I thought I had the game to be on Tour now. I wish I had Charlie around to ask him more questions. Back then I was really very young so I wasn’t really listening. Now being older I would probably ask him a lot more questions.”

Tim and I have been close friends since we first met almost 30 years ago at a junior tournament. He is like a brother to me. Though we took different routes in the game, our lives as African-Americans have had a profound impact on the way we have experienced our careers in the sport. We don’t know the full measure of the rejection felt by Sifford’s generation, but we carry with us the dream that these pioneers had for their place in the game and the responsibility to be torchbearers of their legacy.

As I have tried through the years as a journalist to share stories about the game that reveal its rich diversity, Tim has embodied the spirit of resilience of Sifford, Teddy Rhodes and Bill Spillers. When announcing the exemption into the tournament he hosts, Tiger Woods pointed to the “great determination” that Tim had shown throughout his career. Many black pioneers showed similar grit in helping to pave the way for Tim. Some of those players are still providing vital support to Tim as he continues his pursuit of a life on the PGA Tour.

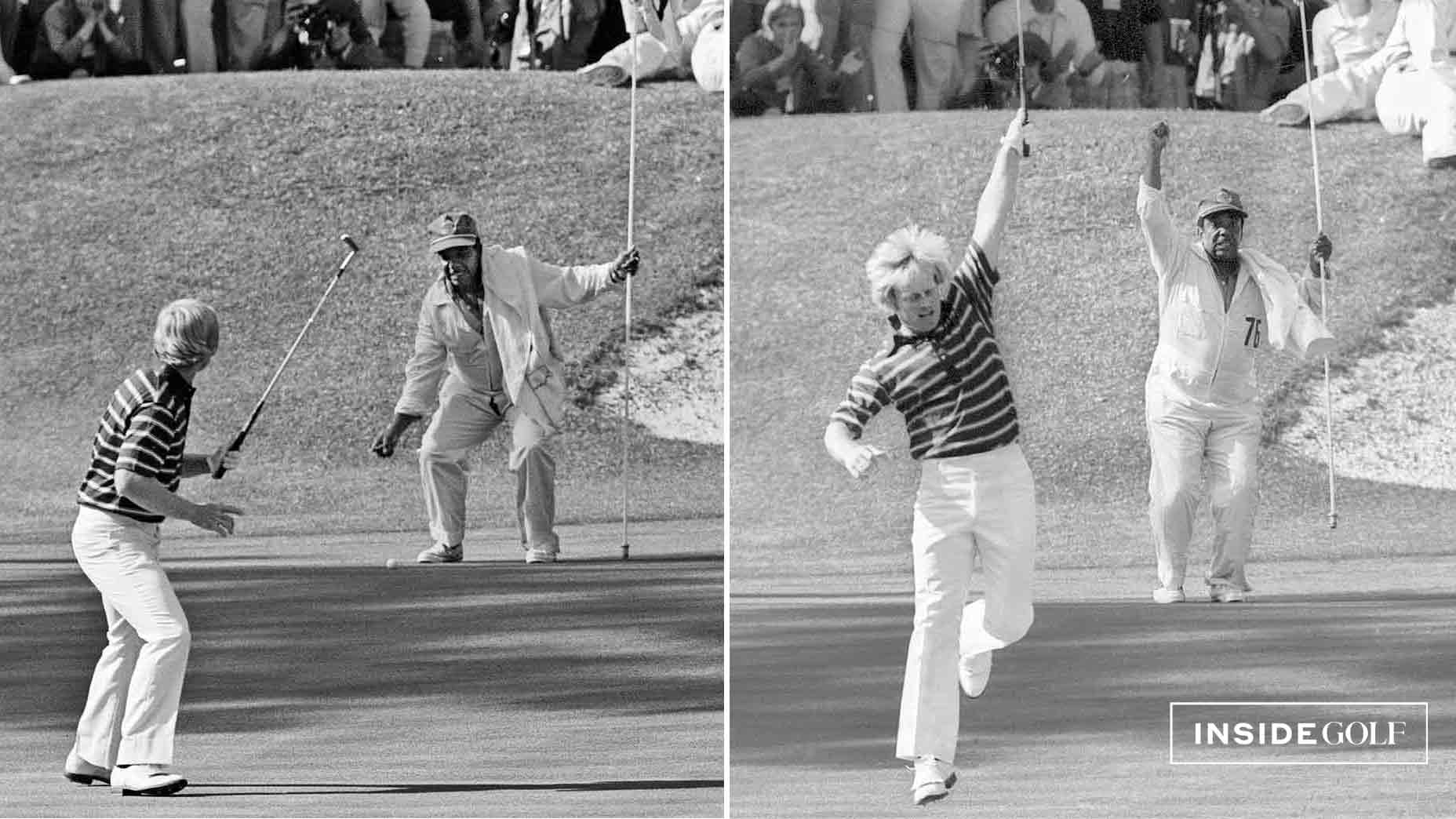

In 1964, James Black, a 21-year-old budding star on the UGA Tour, sold his Spalding irons for $75 to help with expenses on a road trip out west with buddies to qualify for what was then called the L.A. Open. When he arrived in L.A., Black cobbled together a set of clubs to successfully Monday qualify for the tournament. Before the start of the event at Rancho Park, Arnold Palmer gave him a set of his company’s irons. In the first round, Black shot a 67 to lead the tournament before finishing 9th.

Black, 76, is now O’Neal’s mental coach. They have spoken regularly by phone since they began working together more than a year ago when they were introduced by O’Neal’s swing instructor, Bill Currence. “I don’t even look at golf the same any more after working with James,” Tim says. Black believes that Tim’s mind has held him back. “Tim’s already proven that he’s good enough,” Black said. “He’s got to go into Riviera with a lot of fire. It doesn’t make any difference who’s in the tournament. He’s got to know himself. He has enough knowledge about his golf swing. It’s about seeing it in his mind. He has to see and do it.”

Currence, who teaches in Deltona Beach, Fla., has helped Tim learn how to consistently hit the ball right to left. Tim had become a one-dimensional player. He could block out one side of the course with his fade, but he couldn’t attack left-side pins or dogleg-left holes. With Currence, he has learned to stabilize his right side to dependably hit a draw in all conditions.

Despite having a more complete game and better mindset, Tim has faced other obstacles. For most of his career, he has struggled to sustain sufficient financial backing. With the exception of some early support in his career from a group led by Wade Houston, the father of former NBA player Allan Houston, and later from the actor, Will Smith, Tim has been the consummate eat-what-you-kill pro. He came close to retiring from pro golf in 2011, before receiving a life line through a series of mini-tour events in Morocco, where he won three out of seven starts in 2012. “When I almost quit, my mother told me that I should keep playing,” Tim said. “She said, ‘You’re too good to quit.’”

Two wins on the PGA Tour Latinoamerica tour in 2013 helped him get back on the Web.com tour, where he has played 151 events. But he was derailed again when his marriage fell apart during the 2014 season. “I just wasn’t focused as I should have been,” said O’Neal, who shares custody of his two teenaged children with his ex-wife. “I’m on the road trying to make it and then going through a divorce was very tough.”

Since last playing regularly on the Web.com tour in 2014, Tim has pieced together a living on the PGA Tour Latinoamerica and by playing an assortment of state opens and mini-tour events. The Advocates Pro Golf Association, a tour for minority golfers, has also given Tim a steady place to play through some of his ups and downs. He has won five times on that circuit and in 2018 was named its player of the year, which helped him become a finalist for the Sifford exemption.

The Advocates tour is the brainchild of former PGA Tour player Adrian Stills and former Nestle executive Ken Bentley. Beginning with their first event in 2010, they set out to build a tour modeled after the old United Golf Association tour that would give the top minority players a low-cost opportunity to develop their games. When Sifford and Black couldn’t play the PGA Tour, they had a home on the UGA Tour, where they were able to build their lives as professional golfers in much the same way black baseball players had done with the Negro Leagues.

“A lot of our players are close to making it the tour,” Bentley said. “A big part of what’s holding them back is finances. I want a couple of guys from our tour to be able to make enough money so that the next year they won’t have to worry about money the following year. We’re trying to raise the purses so that we can take money out of the equation.

“We can’t charge our guys more for entry fees. We even find ourselves helping guys pay for doctor’s visits and transportation to events. We see ourselves as an organization that has to help our guys with a host of needs if we want to see them get to the PGA Tour.”

Stills could have benefitted from an organization like the Advocates tour when he was a young professional in the late 1980s. In 1986, Stills, a South Carolina State graduate, earned his PGA Tour card in the Q School and made his Tour debut that year at the Genesis Open. Nearly half way into the season, his sponsor withdrew financial support. One of Stills’s brothers convinced 15 donors to each contribute $1,500, which allowed Stills to finish the season. At the end of the year, he missed retaining his tour card by two shots at Q School finals and never made it back to the tour. Eventually, he returned to his hometown of Pensacola, where he is the head pro and general manager of the Osceola Municipal Golf Course.

For Stills, Tim represents everything good about the Advocates tour. “Tim is the elder statesman on our tour,” he says. “The players know how good he is. They watch him and take notice of how he handles himself.

“I admire his tenacity. You would not guess that this guy is in his 40s. He has gone through a battle. He has come so close to getting to the big stage. He just needs that one break to get out there on tour.”

This week at Riviera could be that big break. Tim is one of four African-Americans in the field along with Tiger Woods, Harold Varner III and Cameron Champ. He would love to one day join them as PGA Tour members.

“I believe that I can still play,” he says. “It definitely hasn’t gotten easier with some of the low scores that are being shot. It’s just one of those things where you have to keep grinding and practicing. I think I’m in a good place. I just have to keep doing what I’m doing.”

Farrell Evans formerly covered golf for ESPN.com and Sports Illustrated.