I once told the musician T Bone Burnett that one of the things I like most about golf is how it fosters friendships. This was by email. In response, T Bone wrote, “That is, of course, true, but you could say the same thing about Renaissance Faires or Civil War reenactments. Or anything, really. What I love most about golf is the solitude of it. You initiate every action — alone.”

You may know the name T Bone Burnett. You may not. (He’s Joseph Henry Burnett III on his birth certificate, issued 70 years ago. He was born Jan. 14, 1948.) T Bone is the perfect example of a secret legend. He has backed Bob Dylan and produced Elton John. He has won 13 Grammys (thanks in part to his work on the soundtracks to “Walk the Line,” “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” and “The Hunger Games”) and an Oscar for “Crazy Heart.” (He reveres Johnny Cash and counts Jeff Bridges as a friend.) When I asked T Bone if he was in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, he said, “God, no.” In recent months, he’s been assembling a band, securing a bus, planning a tour — and hitting balls. Regarding his round-number birthday, T Bone said, “Seventy feels like 30, without the anxiety. If I can make a few putts, I look forward to shooting my age one of these days.”

I met T Bone about four years ago, when a mutual friend invited both of us to play Merion. As a golfing presence, T Bone was spectacular. He hit powerful, high drawing tee shots and wore a bucket hat. He’s distinctive: tall, with long, straight fine hair and little round glasses, and he has the low, slow voice of an early-morning host on a classical radio station. T Bone told me he went to the same high school — R.L. Paschal, in Fort Worth — as Dan Jenkins, who is 20 years, almost, his senior. (Ben Hogan went to the same school, though it was known then as Central High.) Jenkins is the Lenny Bruce of sportswriting, a serial mocker of the absurd and the precious, and he brought Hogan, Fort Worth and its Goat Hills golf course to life in a string of articles and books.

[image:14037894]

When I gave Jenkins a report on T Bone, he wrote back, “T Bone is a talented musical dude who is best known around this bureau for telling Vanity Fair that two of his favorite writers are Jenkins and Dostoyevsky. He grew up near Goat Hills, which may explain his literary taste. Only Hollywood can be blamed for the hat.”

Actually, T Bone wore that bucket hat around Merion without irony. His golf-course look is a holdover from an earlier, simpler time. In another game, when we played through a constant drizzle that we never discussed, T Bone wore a cardigan and a button-front shirt. In a Los Angeles round this summer, he came with one of those little canvas carry bags, along the lines of the one he carried as a kid in Fort Worth, though surely more expensive.

While I was at the Masters a few years ago, T Bone wrote, “Please give my best to the venerable Mr. Jenkins. I hope to meet him again someday. We first and last met when I was about eight, when he came over to our house to interview my dad who had given a friend from Arkansas a pig wearing an Arkansas jacket before the TCU-Arkansas football game. We have a great old mutual friend, Vance Minter. Vance is Magoo, in the Jenkins books. Vance and I have sat up many a night discussing the close parallels between B.J. Grooves and R.R. Raskolnikov. I’m pulling for Spieth.”

I am acquainted with Bobby Joe Grooves, who appears in the Jenkins novel The Money-Whipped Steer-Job Three-Jack Give-Up Artist. Raskolnikov’s identity came back to me only after a Google search. He’s the murderer who carries Crime and Punishment from start to finish. As for the Spieth reference, T Bone roots for Texas.

He lives in Los Angeles. With 70 on the horizon, and my own Philadelphia courses more frozen than Greenland, I figured now would be as good a time as any to gather in one place a sampling of the wit and wisdom from my cross-country pen pal. Looking at the correspondence, I see that T Bone’s sense of mirth is one of his calling cards. Here, for example, is his commentary on the gifting of that jacketed pig, an event covered by Jenkins for the Fort Worth Press: “Fort Worth was a little sleepy in those days.”

His hometown is a recurring theme. In one email he wrote about how he grew up playing at Fort Worth’s Shady Oaks Country Club, where Hogan lunched daily:

“Hogan would sit in the clubhouse at a table in the window above the range. It was always a possibility that he would be watching the cats out there trying to dig a swing out of the dirt. You got used to that.

“But some days, you would be hitting balls on the range and suddenly feel a presence behind you. You would look back and Mr. Hogan would be standing there looking at you. You would turn back around and try to forget he was there and keep hitting balls. After a few shots, maybe a particularly solid one, you would look again, and he would have vanished.”

In another email datelined (in a manner of speaking) Fort Worth, T Bone made a nod to his mother’s friendship with Hogan’s wife:

“Valerie Hogan and my mother were women about town. I don’t know much, if anything, about their relationship other than my mother was fond of Mrs. Hogan. They were old people.”

Another email was a longish Fort Worth childhood reverie:

“When I was growing up, we were told that because we had Carswell Air Force Base and General Dynamics, Fort Worth was the number three Russian nuclear target. On the first afternoon of the Bay of Pigs crisis, I got to the Worth Hills golf course after school and was told by the pro, Son Taylor, that we were at war with Russia. I was not surprised or even particularly alarmed. We were all in a permanent state of alarm. So I carried my bag to the first tee thinking that I probably wouldn’t make it through the front nine, but that if I had to go, that was where I wanted to go, out on the course.

“Sometime later, when we were mired in Vietnam, B-52s built at General Dynamics and deployed out of Carswell circled town night and day. I later found out that they would take off from Carswell to the east, circle the town and head west, refueling over the Pacific Ocean before dropping bombs on Vietnam then heading back to good old Fort Worth.

“Growing up there, Fort Worth felt like a city with a low ceiling. That Ben Hogan was able to grow up rough under that low ceiling and conquer the world was important to all of us. There were musical inspirations as well. Ornette Coleman had made it out of there and had torn a beautiful tear in the fabric of our culture. Van Cliburn was the preeminent classical pianist in the world. And Dan Jenkins made maybe not sense but at least tremendous fun out of a place that seemed at the time frightening and unfathomable.

“We were kids who watched and then inherited all the wild games Jenkins and Magoo and Foot the Free used to improvise and play on and around the world’s hardest fairways at Goat Hills. It was our goal to carry on their high jinks. To me, Goat Hills was a semi-holy place. Dan Jenkins said that when the course was sold to TCU, and the bulldozers came in to break ground and begin to build dormitories, we were all happy to know that anything could take a divot out of those fairways. Jenkins was also a damned good golfer. Not like Hogan or Byron Nelson or Ernie Vossler, but he could shoot 68 any day of the week.”

Vossler went to Paschal High, too. He was a few years older than Jenkins and he played and won on Tour in the Arnold era. A lot of talent came out of Fort Worth.

There’s a pattern in our exchanges. A topic would come up on the golf course, get interrupted by a shot in the woods or something, and be revisited later, via the magic of email. For instance, in one of our games, T Bone said he was drawn to the color green. Later, I asked him about that. He wrote, “I will risk sounding like a West Coast therapeutic talking like this, but there is a wealth of lore that says green is restful and peaceful. This is from a website called bournecreative.com: ‘Green also brings with it a sense of hope, health, adventure and renewal, as well as self-control, compassion, and harmony.’ It’s not hard to see that calm self-control is the essence of golf. It is also the part I have the most trouble with.

“When I am playing my best golf, it is a similar conscious/unconscious, trying/not trying state I have when playing music. Performance demands relaxation. The color green promotes relaxation.

“I like the idea that green promotes hope. But hope on the golf course will kill you.”

And that was our only exchange on that subject.

[image:14037897]

After a round where T Bone played beautifully—by which I mean about 50 of his 85 or so shots could have been played by a legit 3-handicapper — I asked him why he didn’t play competitive amateur golf. For starters, he’s four or five inches over six feet, makes a full, rhythmic swing, and he can absolutely pound it.

“I’ve always been too high strung to play competitive golf,” he wrote back. “I played some tournaments when I was a kid and managed to make it through without breaking anything — especially par — but it was only on the rare occasion that I was able to settle into the demands of medal play. The best I was ever able to score in competition was maybe 150 for two rounds.

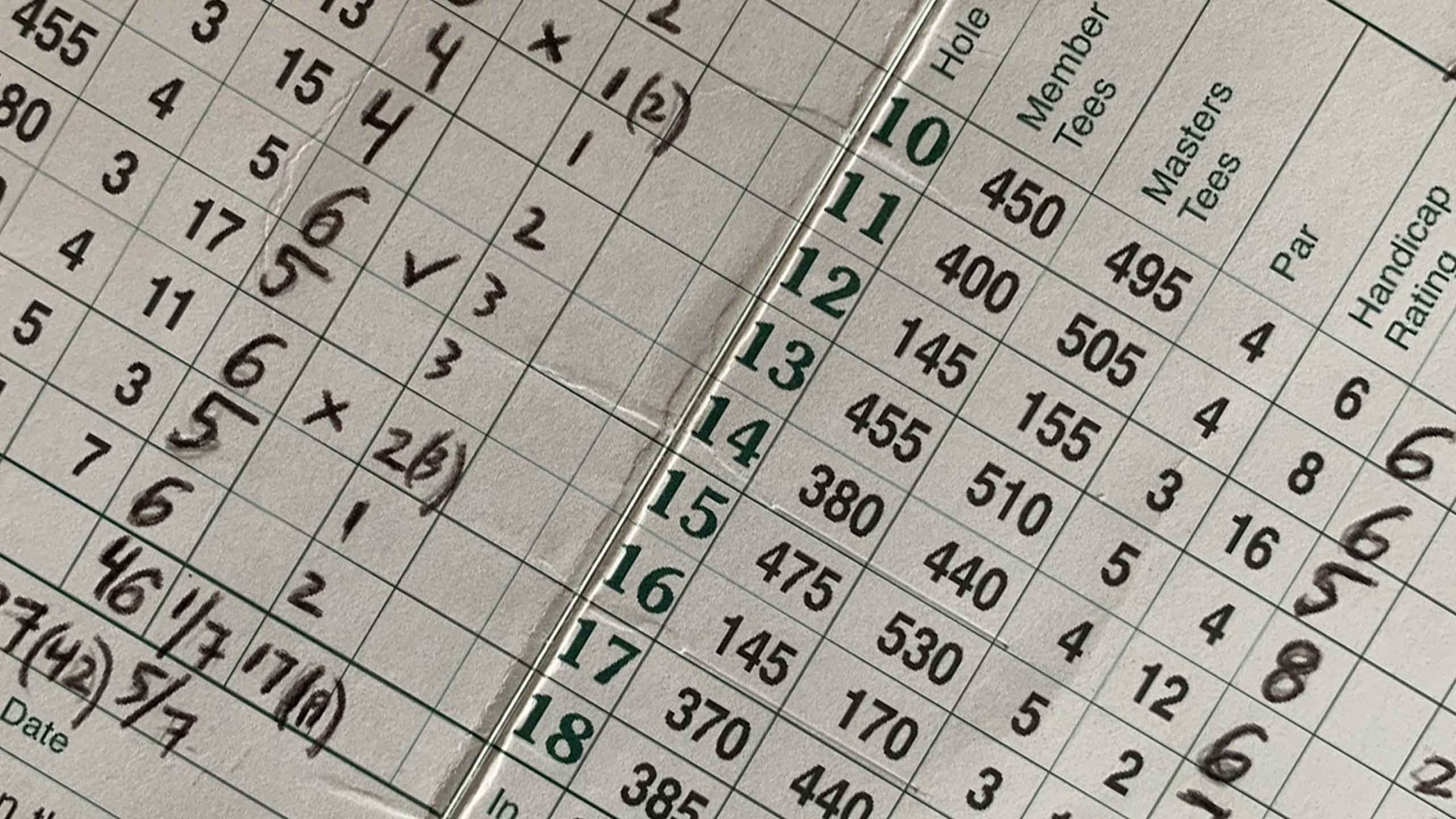

“In my later life, I have had a few very fun rounds in tournaments. Some years ago, I was a partner in a member-member event at Sherwood Country Club here playing with a very good golfer named Jim Fulgentis. The last nine holes was a combined total medal, whatever you call that game. We shot a 68. I had five birdies and a double bogey and a triple bogey to shoot even par. Jim shot four under. We won the gross by a shot.

“But my nerves have not been able to take competitive golf for many years. If ever. I play golf solely for enjoyment now. The score means nothing to me. The quality of the shots is all I care about now. A well-struck ball is the only reward I seek from golf. Really, all I care about is making it around with my sense of humor intact.”

He does that. Over post-round refreshments, he might discuss Bob Dylan’s golf game, the proximity of the Playboy Mansion to the Los Angeles Country Club, his father’s ambitions as a baseball player, his own (now shelved) plans to rehabilitate a minor-league ballpark in Nashville, the TV series “Nashville,” produced by his wife, Callie Khouri. His subjects and themes are all intertwined. He’s absorbed by the audio quality of recorded music and the technology behind it. Once, when describing Hogan practicing, he said, “His shots had the most amazing audio, like a howitzer going off, not that I know anything about howitzers.” From there he might go to, say, to a novel or a movie or a play with ringing howitzers as a chorus. His range is wide and he sees the connections between seemingly disparate things.

When the playwright and actor Sam Shepard died in July, T Bone sent me this note: “Too many people dying. Sam Shepard just left us. One of my oldest friends. We played Pebble Beach together not that long ago. I eagled the second hole with a 50-foot putt and shot a 74. It was a still day. We had drinks in the Tap Room after the round. That was the most fun I ever had there.” Golf with Sam Shepard.

It was about then that I said something to T Bone about golf as a place to develop friendships, and now I will give you his full Renaissance Faires response:

“That is, of course, true, but you could say the same thing about Renaissance Faires or Civil War reenactments. Or anything, really. What I love most about golf is the solitude of it. You initiate every action — alone.

“It is you and the golf course. And there is great pleasure in heading out to the range to practice. Hogan, of course, was the Moses of practice. It was amazing to watch him. He had a couple of semi-private spots at Shady Oaks that he liked. He took his time. He would hit a shot, light a cigarette, write in his book, check the clouds maybe, then hit another shot to the bottom of one of the clouds. He was always practicing trajectory. He said that if you could control trajectory, you could control distance. He would have the shag boy go out about 150 yards and put the shag-bag down in front of him. About two or three times a session, he would slam dunk the shot into the shag bag.

“It’s not for everybody, but for those of us who like that sort of thing, golf is a great solitary meditation. The golf swing is a Tai chi move. It is all focus and concentration. Nicklaus said that when he was on the tee, his concentration would be about 60 percent and the closer he got to the hole, the higher his concentration would be, so that by the time he got over a putt, he would be at 100 percent. Then, after he made the putt, he would go down to zero and walk in that state to the next tee where he would wind back up to about 60 percent for his next shot. I would like to have one percent of that kind of focus and discipline.”

If T Bone Burnett would write a golf book, or any book, I would read it. If you play golf with T Bone, you’ll find he spends a lot of time, pre-round, on the range.

I saw that at our first game, at Merion in 2014, T Bone in his bucket hat. He had brought with him his friend R.J. Harper, the longtime frontman and executive at Pebble Beach. A great guy and a true gent. In November, R.J. died at age 61, of cancer. T Bone sang at his memorial service. He wrote this to me about Harper:

“R.J. was the most gracious person I have ever met. I’ll bring Sam Shepard back into this. We had just finished the premier run of Sam’s play The Late Henry Moss, in San Francisco. (I did the music.) Sam and I decided to stop by Pebble Beach on the way down to Los Angeles and play a couple of rounds. R.J. invited us for dinner and drinks, which went deep into the evening. These were two guys from very different parts of my life — the golf world and the bohemian downtown New York art world, where I feel most at home. Some might have thought that Sam and R.J. would be like chalk and cheese, but the conversation flowed freely, it was wide ranging and it was as entertaining as all get out, as they say back home.

“After we finished, R.J. went one way and Sam and I headed out. Sam, who had a way of summing things up, said that R.J. had a ‘lively intellect.’ I can think of no more accurate or concise description of the man. R.J. was a good football player in college. He played guitar and sang hillbilly music — a weakness he, Sam and I shared. He was a golf professional. He was culturally curious. He was well informed. He was generous. He was empathetic. He was deeply interested in life. He was filled with good humor. In my life, at least, he was the soul of golf. But he was more than that. He was a true friend, and I mean that in the broadest and most precise sense. I write this with a tear in my eye. I am so sad about losing R.J.”

At about that same time, I lost a close friend of my own, suddenly, a man with deep roots in golf, a man on a lifelong quest to figure out life, until his own ended in a cold river. I would say of my friend Fred many of the things T Bone said about R.J. After Fred’s death, I kind of went into a hole for a while. Nothing serious, I was just kind of awash in … blehblahbluh. Then, in the short days of late December, I got this note from T Bone:

How are you? Where are you? I’ve started playing again, once and a while. When do you get out to Los Angeles again?

I hope to see you soon.

All good wishes,

T Bone

Have, if you like, your Renaissance Faires and Civil War reenactments. I’ll take golf.

Michael Bamberger may be reached at mbamberger0224@aol.com.