The scariest part of the U.S.’s latest Ryder Cup disappointment wasn’t the golf

The United States suffered another disappointment at the Ryder Cup.

Getty Images

ROME — It was a scary Sunday to be a fan of U.S. golf. Just perhaps not for the reasons you realized.

In what has become fairly predictable history, the Ryder Cup ended on Sunday evening in Rome in a European victory. For the seventh straight time, the United States Ryder Cup team traveled to Europe to play in the Cup and lost, a streak that now spans 30 years and at least three generations of American Ryder Cuppers.

The latest defeat, a 16.5-11.5 throttling at Marco Simone, wore all the same signs as the ones that came before it. The Europeans rode a rabid crowd, a loud crowd, to an early spate of momentum. They dominated in foursomes play, throttling any hopes of a U.S. charge in both morning sessions. They proved relentless in fourballs, even in the face of a more talented American side, stealing a few points on gutsy halves and ambush victories. And on Sunday, they stepped on the U.S.’s throats, winning a disproportionate percentage of the perceived “50-50” matches en route to a trophy-lifting celebration.

The characters might have been different, but the story was the same. So why, exactly, was the U.S. so surprised by it?

Some of the blame can be placed squarely on the shoulders of U.S. captain Zach Johnson, whose American team looked overmatched, outmaneuvered and generally lifeless until about 5 p.m. local time on Friday. The U.S. lost its first four matches handily, halved three matches it should have won in the following session, and didn’t claim its first full-point victory until the third match on Saturday morning — an alternate-shot session that also included the biggest blowout loss in Ryder Cup history.

If the performance wasn’t bad enough, Johnson seemed out of his depth even in trying to explain it, largely declining to acknowledge the European advantage or the Americans’ sleepwalking start to the event. Even after it was all over on Sunday evening, Johnson neglected to address any of the specific strategic or competitive differences that led to the Europeans’ lopsided victories, chalking up large amounts of the tournament’s outcome to good fortune and … the infinite possibility of the universe?

“This is a moment where you literally just have to accept that the European team played really, really good golf,” Johnson said Sunday. “And that is really my freshest reflection right now, is that Luke’s team played great, and my boys rallied and fought.”

In Johnson’s defense, the U.S. showed admirably on Saturday evening and Sunday, rallying behind Patrick Cantlay’s hatless crusade and creating 45 minutes on Sunday where it looked as though they might even have a chance to win. Some of Johnson’s players, Max Homa and Justin Thomas among them, showed the fight the team so desperately needed, rallying the Americans from off the mat and uniting the team heading into Sunday. But to point to the U.S. response in defense of Johnson’s captaincy is to ignore that the Americans were caught sleeping in the first place — and have been at every road Ryder Cup for the last three decades.

It was Johnson’s job to understand these dynamics, to craft his pairings to give the U.S. the best chance to succeed in a hostile environment. A hot start would have gone a long way toward doing that. Instead the Americans had three alternate-shot pairings that needed all of five holes to effectively lose their matches.

“There’s no perfect formula to it,” Johnson said Sunday. “The formula this week is they got off to a great start, and that momentum led them into a pretty nice lead going into today. And our boys fought like madmen and made it interesting, you know, made them earn it.”

Johnson’s right. He might have pulled every correct lever this week and still found himself on the losing end of this weekend’s wager. The Europeans really played that well, and some of his American players really struggled that much.

But the point is to pull all the right levers anyway — to acknowledge that the last three decades of misery represent more than just a pesky statistical anomaly and to employ a defined strategy to address it. Johnson never seemed to have that all together in Rome.

For what it’s worth, ZJ wasn’t the only one left at a loss. His players were similarly befuddled by the European dominance they had just witnessed, and more pressingly, what they could have done to stop it.

“It’s tough,” said Rickie Fowler, loser of four Ryder Cups and who went 0-2 in Rome. “Damn, they definitely take advantage of those opportunities, especially on home soil, making putts, chipping in, and those are big momentum shifts.”

Brooks Koepka agreed, saying, “This week, they just holed a lot more putts, a few more chip-ins.”

Sometimes, as Koepka and Fowler pointed out, golf can be as simple as the difference between holed putts and missed ones. But are we really supposed to believe that European home-soil dominance can be distilled down to the Europeans consistently making more putts every four years for the last three decades? Wouldn’t mean regression give the U.S. at least one victory in that time? Wouldn’t luck eventually fall in their favor?

Of course it would. Every golf fan since the Clinton Administration has attempted to parse out the secret behind Euro dominance, but the closest we’ve gotten to an answer is this: It’s all of the things. The crowd, the leadership styles, the team bonding, the course knowledge, the course setup, the style of golf and, yes, the number of putts made. The Americans have lacked in some or all of those ways over the last 30 years of Ryder Cup losses, and the Europeans have made them pay every single time.

But it was concerning that Jordan Spieth appeared to be the only American team member willing to admit the answer was even slightly more nuanced than a swift kick in the rear end on Sunday evening, the night the streak extended until at least 34 years.

“I think we would probably say, give us a week after the Tour Championship or two weeks after and then go, instead of five,” he said of the Ryder Cup’s current schedule location. “If it were tighter to our Tour Championship and/or even if it were later and we had more of an opportunity to get a little rest and play more of an event or something, then it helps a bit.”

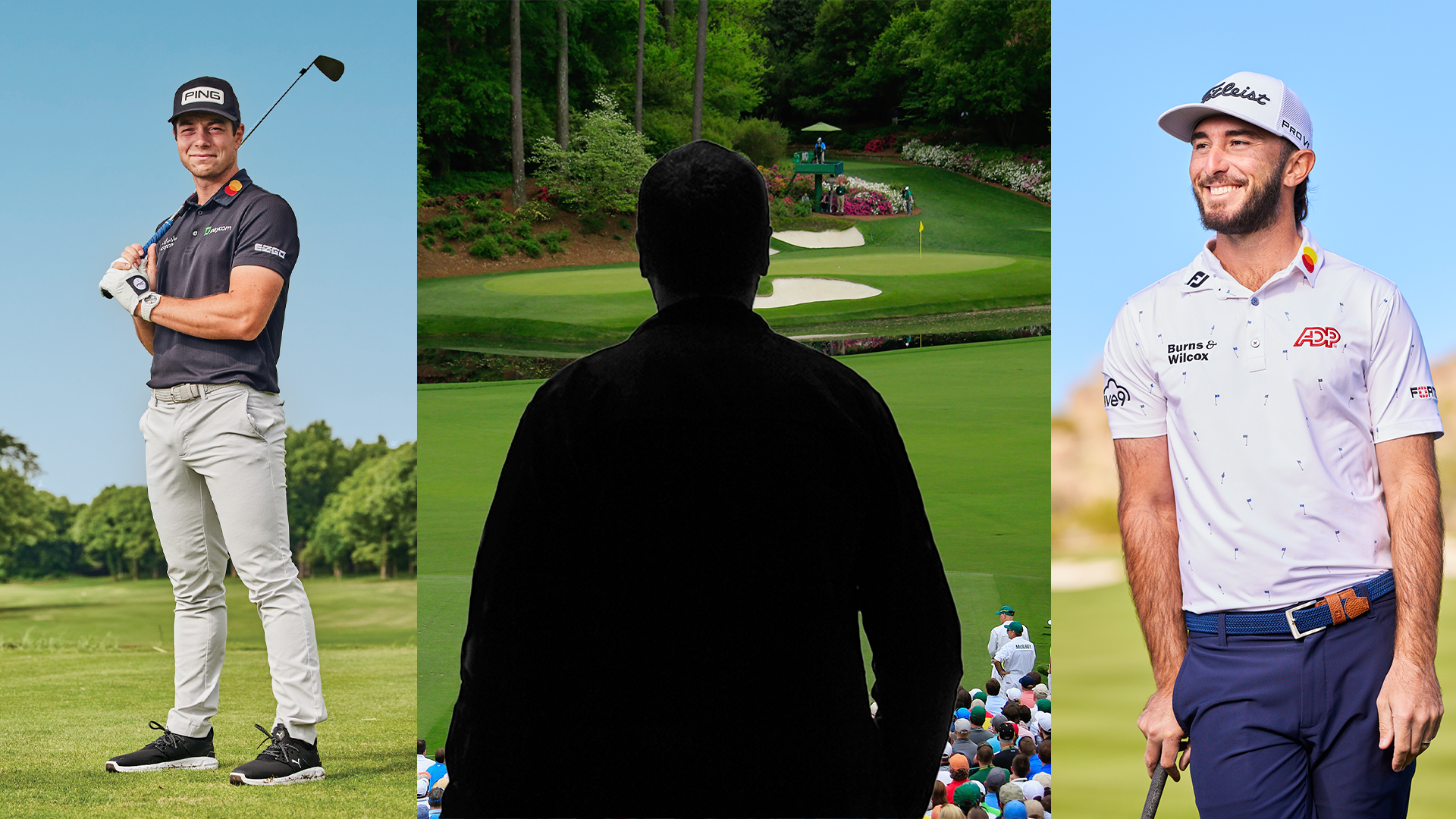

Spieth was the only one to offer an answer of any kind Ryder Cup Sunday — a day the Europeans appeared on the glimpse of their own youth movement, riding their new three-headed monster of Rory McIlroy, Jon Rahm and Viktor Hovland to a worryingly dominant win.

But if you were a fan of U.S. golf, the really scary moment came after, when Johnson addressed the media for the first time.

“We’re going to learn from this,” he said. “I mean, that’s what Team USA does.”

He was right on at least one account — Team USA had learned something from three decades of European failures.

Every losing captain before him had said the same thing.