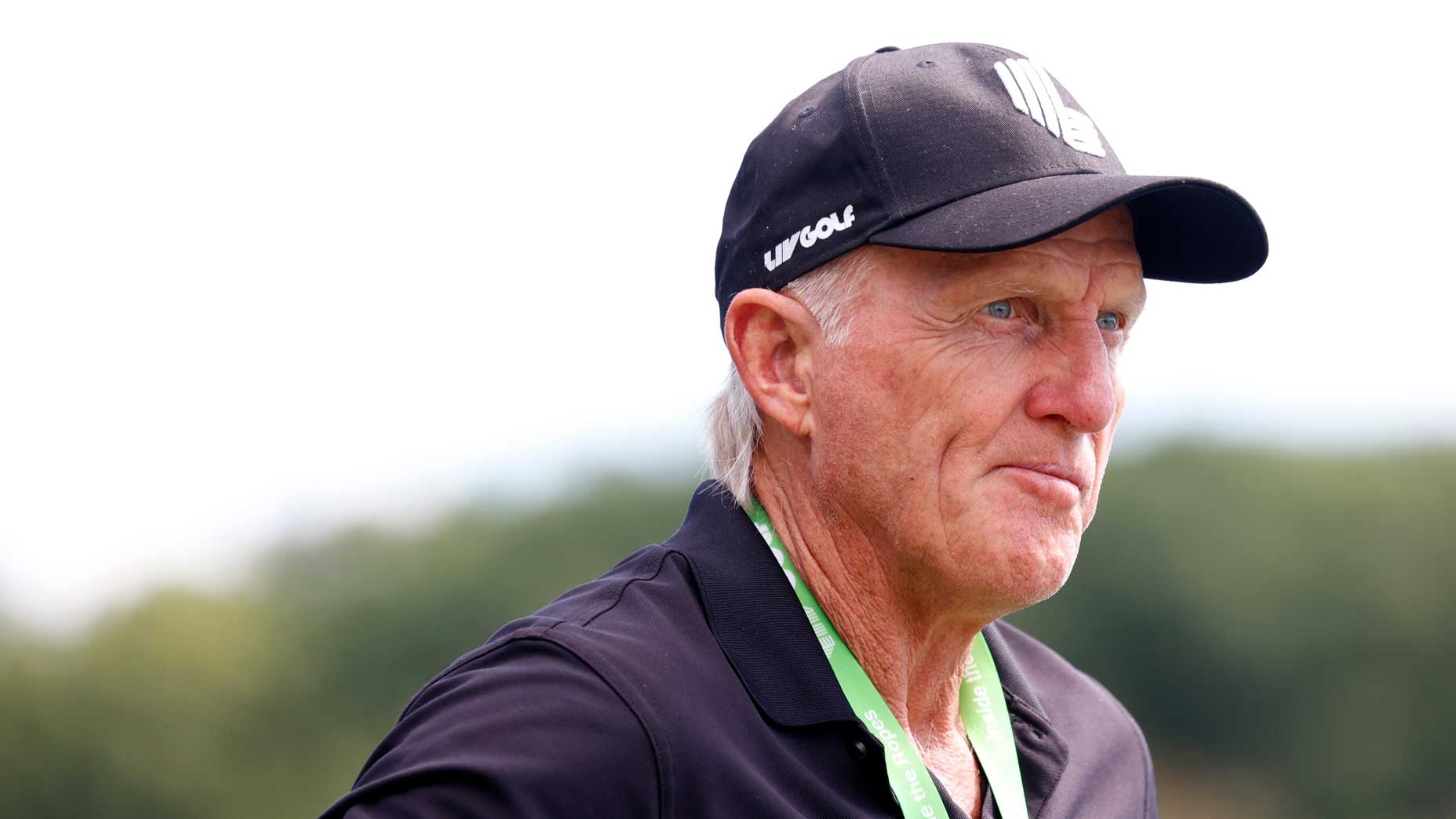

Inside Greg Norman’s complicated relationship with Medalist Golf Club

Greg Norman co-designed Medalist Golf Club with Pete Dye.

Michael Bamberger is back on the road, keeping two club lengths from his sources. This is the final installment in a five-part Bamberger Briefly series from South Florida, about golf’s return to action. You may read Part 1 here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here and Part 4 here.

HOBE SOUND, Fla. — Jack Nicklaus has his own South Florida golfing home, the Bear’s Club. Nick Price does, too, McArthur Golf Club. Raymond Floyd has Old Palm. Phil Mickelson hasn’t moved to these parts yet, but when he does, he’ll be the most accomplished golfer at Grove XXIII, Michael Jordan’s new club.

Then there’s a club that’s older than any of those four, Medalist Golf Club, a club Greg Norman founded here with two other men in the early 1990s and co-designed with Pete Dye.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if security came up and asked what I’m doing here,” Norman said on Thursday morning, as he made a leisurely drive in a cart around the course. The day was cloudless, sunny and hot. Norman was joking, to a point.

For years, what the Bear’s Club was to Nicklaus, Medalist was to Norman. But Norman knows that these days most golf fans associate Medalist principally with one golfer, Tiger Woods his own self. Come Sunday — when millions watch Woods and Peyton Manning play Phil Mickelson and Tom Brady in a made-for-TV, do-the-right-thing charity match — many more will associate Medalist with Tiger.

In actual fact, Greg Norman, who plays almost no golf these days, is still a member in good standing. When he does come to the club, he arrives, says hi and waits for the security guard to open the gates. Norman then rolls on in, no questions asked.

In my few visits to Medalist in recent years, I don’t recall seeing any photos of Norman, or any of his golfing artifacts, in the clubhouse. There’s a display case near the entrance to the men’s locker room with smiling photos of the Medalist members who have won major titles: Nick Price, Brooks Koepka, Justin Thomas. Tiger, of course. Olin Browne, winner of the 2011 U.S. Senior Open. But there’s no photo of Greg Norman, a two-time winner of the British Open.

On a neighboring wall is a signed Augusta National flag from the 2019 Masters: To Medalist, Thank you for all your love and support. Tiger Woods. Medalist is Tiger’s golfing home. The club gives him both space and camaraderie. (Norman once would have said the same thing.) Tiger plays a lot of golf with his son at Medalist. (Norman would have once said the same thing.)

For years, Norman ran the club. Then, by the terms of the club’s charter, he ceded control to others. For years, no changes could be made to the course without his approval, and later a whole series of changes were made of which Norman did not approve. In 2012, Dye and Norman wrote a letter to the club demanding that the course no longer be considered a Dye-Norman design.

Well, anyone who watched Norman at the height of his powers knows he could run hot. Seve and Arnold and Sam Snead could, too. Jack Nicklaus and Tom Watson and Ben Hogan were built to run cool. Everybody’s different.

I played the course when it first opened, and I’ve played the course a few times over the years. It doesn’t matter what Norman and Dye wrote in that letter: It’s a Dye-Norman golf course. Alister MacKenzie would be freaked out if he saw Augusta National today. You could imagine his text messages to Fred Ridley, protesting the rough, the manicured bunkers, the width of the creek on 12. The green speed. But nobody would ever say that Augusta National is not an Alister MacKenzie-Bob Jones course.

It so happens that Dye and Norman often referred to the MacKenzie course at Royal Melbourne when they were building Medalist. That subject came up when Norman toured the course on Thursday. Norman said the course would not exist without Dye’s insights into subterranean water flow.

An understanding of hydraulics is the starting point to building a golf course in Florida. The best-known example of that is Donald Ross’s construction of Seminole. Woods, a promising architect himself, has become a student of that subject in creating some backyard holes at his home near here, on Jupiter Island. Norman lives up the road from Woods, and the Mickelsons are building a home farther up the road.

I’ve had a series of wide-ranging conversations with Norman this week, and next week I will report on them. Tiger. (Norman would like to have a better relationship with him.) The Premier Golf League. (Now more than ever, says Norman.) Athletes in helicopters. (Norman flew his own.) Michael Jordan. (Norman has had multiple matches with him.) But for now, on the eve of Match II — The Match: Champions for Charity on its birth certificate — I’d like to leave you with another image. Not a sad Greg Norman. Not an angry or confused Greg Norman. Not an old Greg Norman. (Sixty-five and fit.) More of a wistful one.

This has to be an odd moment for him. He knows, of course, that millions of people, from across the world, will soon be focusing on a golf course that once was his. That they will be watching a foursome unlike any foursome ever assembled. That the match is being played for a purpose that nobody could ever have predicted three months ago.

Medalist will become cemented in people’s minds as Tiger’s home course. Some will drop the word home. When Tiger Woods became the No. 1 player in the world in 1997, the man he replaced was Greg Norman. I asked Norman what was going through his mind in the run-up to the event.

“First of all, it’s a great thing, what they’re doing, raising this money for Covid charities,” Norman said. “I used to do a lot of these kinds of fundraisers. With Formula One drivers. With other golfers. With actors and actresses.

“I think about my kids, when they were young here. I think about Pete and I building just one hole, what’s now the 10th, to show the Audubon Society that we could build the course in a way that was environmentally sensitive. Pete was always aware of the environment. I think about the blood and guts and toil we put into building this course.”

Dye, who died in January at age 94, built TPC Sawgrass, where Norman had one of his most famous wins, the 1994 Players Championship with scores of 63-67-67-67. When he left for Ponte Vedra Beach that year, Norman told Dye he’d destroy his course, and he did. They enjoyed giving each other the needle. Norman spent 331 weeks as the top-ranked player in the world. Dye was one of the most sought-after architects to ever work in golf.

“I think about Pete, at his 90th birthday, down at Gulfstream, with Alice,” Norman said. Dye had suffered from memory loss in his later years, even though he was physically robust. Dye’s wife, Alice, was an architect, too. “I made those remarks to him with a tear in my eye, hoping he could hear and understand what I was saying.”

Norman didn’t trail off into silence. Not at all.

Like most elite athletes, Norman tries not to show hurt. You’d say the same of Tiger, Jordan, Brady. But Tiger Woods is the reigning Masters champion. Tom Brady was the quarterback of the New England Patriots when they won the Super Bowl in 2019. Michael Jordan was the subject of a recent 10-part ESPN documentary watched by millions of people across the world.

Everybody wants to be in the game. But you can’t be, not forever.

I asked Norman if he would have any advice for Tiger on how to prepare for life 20 years from now, when he’s in his mid-60s. No, Norman said — and it would be presumptuous to try. It’s the kind of thing, he said, that a person has to figure out for himself.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael_Bamberger@GOLF.com.