I was standing in an old Black cemetery in downtown Augusta with a new friend, looking to ask him an odd question. To grease the skids, I said something close to this:

“OK, for example, here’s an unsolved Augusta mystery for me. I got this from the man — I’m blanking on his name — who served Cliff Roberts his final meal.”

Cliff Roberts was Augusta National’s co-founder, alongside Bobby Jones. After his death, Roberts was named “Chairman in Memoriam.” A weird but fitting title. He hovers still. When Fred Ridley, the current chairman, spoke to reporters at this year’s Masters, he did it in the arctic, windowless Press Building auditorium with a portrait of Jones on one wall and Roberts on another. The founding fathers.

“I have a picture in my office of the first Amateur Dinner I ever attended,” Ridley said. April 5, 1976. “And in the background, if you look very closely, sort of between two other heads, is Clifford Roberts. That was his last year as chairman.” Roberts was found dead by Ike’s Pond, beside the club’s par-3 course, on a September morning in 1977. He was 83, frail and ill, and the death, by gunshot wound to the temple, was ruled a suicide. Of the many towering figures golf has produced, few are as enigmatic and compelling as Cliff Roberts.

“This waiter was like Roberts’ personal servant at the club,” I said. “I interviewed him in a nursing home.”

We were a twosome, standing on a narrow road in Augusta’s Cedar Grove Cemetery, rustic and still. The April afternoon, a few days after this year’s Masters, was unseasonably warm.

“He said there’s no way Roberts took his own life without help. He didn’t have the strength to walk down the hill from his room in the clubhouse to the par-3 course by himself. His raincoat was misbuttoned. Roberts would never have done that. And Roberts might not have even had the hand strength to handle the gun. So that’s an unsolved Augusta mystery to me: who assisted Cliff Roberts with his suicide?”

You can imagine Lt. Columbo investigating, the follow-up questions. Columbo’s thing was to presume nothing. Everybody’s a suspect.

“Man,” said Leon Maben, the gentleman showing me the cemetery. Some of his people are buried in Cedar Grove and he visits it regularly. Leon, who is 68, lives in downtown Augusta, in the house in which he was raised, with a tin roof and a tidy garden. (Petunias, Boston ferns, Dusty Millers.) He knew the name Cliff Roberts, as many Augustans his age do, but little about Roberts’ death. “That’s something.”

At that moment I looked beyond Leon’s trim, hatted self — he was a shortstop and second baseman in high school — and I saw a tombstone with seven blocky letters etched on its face: WIGFALL.

“Wigfall! The waiter, who served Roberts his final meal? His name was Rayford Wigfall.”

How weird is that?

We walked over to the Wigfall family plot and started reading tombstones.

Then it was Leon’s turn. His turn to tell me his unsolved Augusta mystery.

The Masters ended, but I stayed on. After seven nights in a charming rental house, for the tournament, I moved to the Marriott, downtown. I wanted to see, as an outsider, if I could make a dent in my grasp of Augusta. Black Augusta and public-golf Augusta. Downtown and Sand Hills Augusta. New work-in-progress Augusta. Old-timey Augusta, with its heavy buildings and heavy undertow.

A week in the rental house, then four extra nights. No big whoop.

When I got home to Philadelphia, a friend asked this: Do you think a mysterious force was at work, in that old cemetery, when the waiter’s elusive name suddenly appeared?

No, I don’t think that.

I do think it was a strange coincidence. And I do think strange coincidences are more common in the South than in other places. You could probably do pretty well selling bumper stickers stamped with WEIRD HAPPENS at the UGA bookstore in Athens. Have at it, kids, if you like.

My guess is that this bend toward happenstance comes from the Southern love of history, familial and otherwise. Southerners, in my experience, are more connected to their forebears, and to one another, than most other peoples in most other places. All that connection is like a live wire to coincidence.

You see that every year at the Masters, which celebrates its luminaries, both living and dead, as no other golf tournament does. Baked into the Masters’ DNA is an oral tradition, in which tournament lore is handed down from one generation to the next. The spectators do it. The writers and broadcasters do it. The caddies do it. The members do it. The players, past and present, do it.

The tournament’s various annual dinners assist in this, mightily. There’s one for the amateur contestants on the Monday night of Masters week. That’s the Amateur Dinner that Ridley mentioned. There’s one for former winners on the Tuesday night — the Champions Dinner, started by Ben Hogan. There’s a wrap-up members’ dinner, where the new champ is toasted, on the Sunday night. The Golf Writers Association has an off-campus dinner in a banquet hall in the woods on the Wednesday night. The USGA has an off-campus cocktail party at a downtown church on the Friday night. You’ll also see (in normal times) the game’s movers and shakers having breakfast and lunch in the clubhouse throughout the week. The caddies and players do the same, in the caddie building beside the range. You can’t separate food-and-drink from the tournament. In the South, food-and-drink don’t lag.

And then there’s the gift of Southern geography, the Southern map, dotted with all those little burghs. There’s no anonymity in a small town. You know: You’ll never guess who I saw at the Publix today. Small-town living encourages happenstance. Augusta is Georgia’s second-biggest city, but to Augustans, especially the natives among them, it’s another old Deep South town, like Charleston and Savannah, but without their seafaring charm and Hollywood lighting.

And, finally, this, the most important element: Time. It crawls in the South. “A day was twenty-four hours long but seemed longer,” says Scout Finch, daughter of Atticus and narrator of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, set in fictional Maycomb, Ala. Like time seems for you, maybe, during a power outage after a summer storm. Happenstance breeds in all that sluggishness. I’ll be damned — the unofficial kicker to stories of coincidence — is never uttered when you’re rushing here and rushing there, is it? Nope. Those three words arise only when you’re hanging out. When you’re walking the aisles of the supermarket, sitting in the bleachers at the game. When you’re standing at the bar.

I’ve lived in the Northeast all my life. It’s home and I can’t imagine living elsewhere. But life in the Northeast is orchestrated. (“Let me check my calendar.”) The South has far less of that, a lot more let’s-see-how-we-feel. As a way of life, I’m drawn to it. I’m drawn to winging it.

When you’re in the South, you know it. Despite the proliferation of we-could-be-anywhere Walmarts and no-accent newscasters across cable TV, the South remains Southern. In matters of accent, language, style and sport; in driving, eating, drinking and courting; in politics and religion and race, the South still does her own thing.

The Masters loves ritual. Arnold Palmer used to give the winner of his tournament a blue sport coat and Jack Nicklaus still does at his, a gray one. But only the Masters has not one but two Green Jacket ceremonies. The first event is in the basement of Butler Cabin, for the worldwide TV audience. The second one, minutes later, is outside on the practice putting green, for fans in no rush to leave.

The tourney has evolved over time, of course. (No serious person uses that word anymore.) But the Masters doesn’t change. We know when the tournament will be played. We know the holes and their mounds. We know the customs and the schedule of events, from the Par-3 Tournament on Wednesday afternoon to the chairman’s interview with the winner in Butler Cabin on Sunday night.

That interview has been remarkably consistent through the years. Different winners, different chairmen, same interview. The winner’s heart is racing, but he takes his cues from the room and its history and he uses his indoor voice. He thanks the chairman and the club, he praises his competitors, he compliments the collegiate star next to him, the low amateur. Good manners, really. Every winner, at least for those 10 minutes, no matter his background, becomes a Southern gent.

Over the years, by my rough counting, I’ve logged about 180 nights in and around Augusta. It’s a blip. Still, it’s been enough time for me to realize you could study Augusta for the rest of your life and never truly solve its riddle. But does that mean you shouldn’t try? Of course not.

My mentor in these matters is Lee Ann Caldwell, a history professor at Augusta University. If you want to understand the influence of the Augusta Canal (constructed in 1845) on modern Augusta, Dr. Caldwell is your person. If you want to know more about George Washington’s visit to Augusta’s Richmond Academy in 1791, you know who to call. Dr. Caldwell has been studying her native city for decades. She’s aware that her work will never get done. She wouldn’t want it any other way.

I once heard Mark Calcavecchia say of Augusta, “Can’t wait to get there, can’t wait to leave.” He was talking about Augusta the course (beautiful but confounding) and Augusta the club (elegant but tight). But I imagine he was talking about Augusta the place, too. Dr. Caldwell’s Augusta, Leon Maben’s Augusta. I get it. I have felt the same way some years, at the end of the Masters. But more often I don’t.

I don’t rush out of Augusta when the tournament is over. For one thing, I enter the club’s annual lottery, by which a few sportswriters are selected to play the course on the Monday after the tournament. My name was plucked in 2000 but not since. No big deal. There are lots of other places to play.

That oh-fer is not as epic as it sounds because once you play you’re out for the next seven years. Seven years. There’s something almost biblical about it, in an inverted way. Exodus, Chapter 23, Verse 11: In the seventh year you shall let your land rest and lie fallow, that the poor of your people may eat; and what they leave, the beasts of the field may eat.

I am not, at all, a chapter-and-verser. But Augusta brings out the little I do know. Throughout Augusta, including the club, the pull of church and scripture — and sometimes God — is often in the air, shaping conversations and lives, despite all the distraction modern life serves up in such large portions. It wasn’t always like that. In the club’s early years, you went to Augusta National for the party. But these are different times.

Fred Ridley, at last year’s one-off November Masters, said that Augusta National would be giving $10 million for the construction of a new Boys & Girls Club in downtown Augusta. That gift, in time, will look modest. Over the next decade, the club, with its corporate partners and other agents of change, will likely invest hundreds of millions of dollars in an effort to bring new life to two tired downtown Augusta neighborhoods, Harrisburg and Laney Walker. Can it work? We shall see. It’s an inspiring plan.

That’s how I first crossed paths with Leon Maben, in late winter. I was writing about this nascent project and I called Mr. Maben, denizen of Laney Walker, elder at one of its many churches, trustee of a neighborhood museum. Augusta National has a history of largesse, but it has never attempted philanthropy on this scale before, nor this publicly. I was looking for a local’s take and he had it. Speaking of the club’s leadership, he said, “They had their come-to-Jesus moment.” He’s lived. He’s heard the rich and the well-intentioned make grand plans before.

But things are already happening. There was a groundbreaking for the new Boys & Girls Club on the Tuesday of this year’s Masters week. The next day, reading from prepared remarks at his State of the Masters address, Ridley concluding by saying, “Yesterday’s groundbreaking for the community center was a joyous occasion. It reminded us that our mission to serve Augusta and its citizens is where we can and will make the greatest impact.” Ridley, a measured man and a lawyer, would never use mission and serve casually. He knows what everybody knows: They’re sacred words.

The old hands will tell you that the sale of concession-stand beer doesn’t begin on Masters Sunday until the club gets a call, at the conclusion of services, from an official at the Whole Life Ministries church, across Washington Road from the club. On Sunday mornings in Augusta, and especially in the lower range of your AM dial, you’ll find various local Amen Corner church services. You can be in your car, waiting for a train to pass, and find yourself suddenly transported. On various morning jogs and random afternoon drives over the years, both downtown and in the outer reaches of the city and Richmond County, I’ve seen dozens of churches, many of them tiny, some of them exhausted, all of them (you hope) broadly committed to do unto others, etc.

Among the loveliest of these churches is Cumming Grove Baptist, a Black church in the city’s Sand Hills section. Cumming Grove is separated from the Augusta Country Club driving range by a thick stand of cherry laurels and a tall chain-link fence with a barbed-wire top. (Another fence separates Augusta Country Club from Augusta National.) When the congregation was organized, in 1840, on land deeded to it by the Cumming family, its parishioners were enslaved. I watched an April service at Cumming Grove the other day, courtesy of internet magic. The real magic was the service itself. Their melody for “Amazing Grace” was one I had never heard.

The pastor leading the Cumming Grove congregants in song was dressed impeccably, in a coffee-colored suit that seemed to match his baritone. Just two or three miles from the church, on Broad Street in downtown Augusta — near the statue of a cape-wearing James Brown, Augustan and soul god — there are several stores that sell Sunday-best suits all year long, along with Kangol hats and Stacy Adams shoes. Yes, there are people in Augusta who dress for Easter every Sunday. The ladies, their hats. One of the downtown shops, Ruben’s, has been in business since 1898. Tradition, tradition.

Cumming is an historic surname in Augusta, associated with an old-line white family, prosperous, civic-minded Augustans since the 18th-century. But there are also Black branches of the Cumming family, a name assigned to them by their owners. Just writing those words is painful. Imagine that as the origin story of your life. Being owned. Descending from the owned.

High on an exterior wall at Cumming Grove Baptist, at the church’s epicenter, is a Star of David, a central symbol of Judaism, in a circle of stained glass. I’m putting that on my Augusta mysteries list, the Mogen David hexagram at Cumming Grove Baptist. I’m putting that unexpected melody of “Amazing Grace” on my mystery list, too.

On many Mondays after the Masters I’ve played the Aiken Golf Club, an old-timey public course (1910ish) that’s a half-hour down the road by car from downtown Augusta. (You cross the Savannah River into South Carolina and then it’s a straight shot, north on US 1.) But this year, three young colleagues and I, after sharing an Augusta house for a week, played a public course practically in our backyard, Forest Hills, a Donald Ross course owned by Augusta University with a growing First Tee program.

It’s outstanding. The four of us, walking, played in well under four hours and the green fee per player was not even $50. I went around with a single ball, a Titleist ProV1 stamped with a 40. A Titleist rep gave my friend David Westin, a longtime reporter on the Augusta Chronicle, a box of balls, each one stamped with a 40, in honor of his 40 years of covering the Masters. David honored me by giving me one from his dozen. I honored him by hitting the ball over the water guarding the 13th green. Fly, golf ball, fly!

I said the same thing when I was caddying for Stuart Wilson, then the reigning British Amateur champion, after foolishly talking him into going for the green with a hybrid for his second shot on the par-5 15th hole in the first round of the 2005 Masters. (Wilson was the captain of the GB&I Walker Cup team this year at Seminole.) His ball carried, barely, and sat, surprisingly, on the slope. Talk about answered prayers.

Some of you will know that phrase with an uppercase A and an uppercase P. Answered Prayers is a novel by Truman Capote featuring a woman who “looked as if she wore tweed brassieres and played a lot of golf.” Capote’s childhood neighbor in Monroeville, Ala., was Harper Lee herself. Miss Lee, Capote’s reporting partner for In Cold Blood, logged a lot of rounds on the Monroeville links, dragging on cigarettes and putting on Bermuda-grass greens. Southern living.

It almost seems too easy, to go from Augusta National’s 15th to Truman Capote to Harper Lee — and now to downtown Augusta. The late Jack E. Boone Jr., a civil-rights lawyer in the city, was described as a “real-life Atticus Finch” in his Augusta Chronicle obituary some years ago. He practically lived in the downtown courts, defending the indigent and the lost. His work was a world away but also practically beside the singing congregants of Cumming Grove Baptist, the dining members at the Country Club, the am-I-dreaming guests at the National.

Augusta is dense. Not in the Midtown Manhattan sense of the word, but it’s dense. Everything and everybody can practically touch and sooner or later does.

If you’re way into the tournament, you’ve likely heard of Sand Hills, a historic Black settlement. One of the things I hoped to do, courtesy of my extra time in Augusta this year, was to get to know Sand Hills better.

Earl Woods went through Sand Hills in 1995 and talked about it, at least now and again, long afterward. Earl was half a historian, a man as comfortable looking back as he was ahead. Sand Hills, first settled by former slaves after the Civil War, engaged him.

You’ll hear Ben Crenshaw refer to Sand Hills once in a while, when talking about his life at Augusta. His longtime Augusta National caddie, Carl Jackson, grew up in Sand Hills. Crenshaw won his two Masters titles, in 1984 and ’95, with Carl as his caddie. Crenshaw’s most celebrated course, as an architect, is also called Sand Hills, which opened for play in 1995, some months after his improbable second win. That has to be a coincidence. Right? (The course is in Nebraska, in its Sand Hills region.) Crenshaw’s win in ’95 came days after the death of Harvey Penick, his golf mentor. In victory, Crenshaw was overwhelmed by joy and grief and Jackson was there to hold him. Twenty years later Crenshaw played his final Masters and Carl couldn’t work, so his brother Bud filled in for him. All the Jackson brothers caddied.

In its heyday, Sand Hills produced caddies like San Pedro de Macoris, in the Dominican Republic, produces shortstops. Past tense intentional. Now the Augusta National caddies come from almost everywhere except Sand Hills.

About 4,000 people live there now. That can’t be a record high. Many from Sand Hills are lifelong members of the working class and the working poor. The employed work as laborers and domestics. They work in hospitals and in landscaping. They work at daycare centers and in nursing homes. They work the jobs that keep Augusta running.

Most of the Sand Hills houses have seen far better days. Houses in Sand Hills tend to stay in families. Establishing clear title in Sand Hills can be tricky, for all manner of historic reasons, going back to the Civil War.

After Emancipation, there were affluent white Augustans, many of them living in large houses maintained by slave labor, who gave small plots of nearby land in Sand Hills to their former slaves. Other former slaves bought or leased their own lots in Sand Hills. Black families built modest houses on those lots. Over time, some homey cottages were built, too, typically by doctors or dentists or other members of the small professional class that lived in the neighborhood. But most of the houses were and are bungalows and so-called shotgun shacks, narrow houses where a shot fired through the front door could exit via the rear one.

In its early years as a settlement, Sand Hills residents often continued to work for the families that once owned them. They didn’t need a horse to get to work. They could walk up paths to the big houses on The Hill, and they did. Years later, young Jim Dent got his start in golf walking downhill from his family’s home in Sand Hills to the Country Club, where he caddied.

More than a few men from Sand Hills made it to the PGA Tour as caddies, but only Jim Dent made it as a player. Later, as a sweet-swinging, long-hitting star on the senior tour, Dent helped put the original Callaway Big Bertha driver on the national golf map.

Sand Hills is residential. There’s no commercial district there. As best I could tell, there’s one neighborhood corner store, owned now and for generations by a Chinese family, and you don’t go there looking to buy baby arugula. Nearby is an empty dirt lot where long-retired Augusta caddies, and other men of various ages, hangout on an assortment of chairs, metal and wood, day and night, refreshments (sometimes) in hand. Every day there is game night.

Tiger’s first Augusta caddie knew the territory well. Woods played in his first Masters in 1995, while a freshman at Stanford, and his caddie that year was a Sand Hills man named Tommy “Burnt Biscuits” Bennett. It was Bennett who showed Tiger and his father around Sand Hills. Earl liked to credit the old caddies for sharing putting tips that Tiger used so effectively. For example: When in doubt, play the putt to break toward Rae’s Creek.

I’ve been to that Sand Hills lot several times over the years, and it’s a trip, in every sense. This year, I drove by one warm night, near sunset, and it was packed. I slowed down but didn’t stop. It seemed on edge. As it happens, the Augusta Chronicle ran a story the next morning with this headline: “Sand Hills gathering spot draws complaint from new neighbor.” One of the claims was that police patrol of the lot is inadequate. I spoke to several people about the story, and the issues raised in it, and they thought it was much ado about nothing, or at least nothing new.

There’s more to unpack here than I am qualified to discuss. The relationship between Augusta’s Black citizenry and local law enforcement is complicated, and has been long before the city’s 1970 race riots. On its 50th anniversary last year, NPR released a podcast called “Shots in the Back” that detailed the deaths of six Black men, shot in the back by white officers. All these years later, the tragic legacy of that riot endures.

The relationship between Black Augusta and the Chronicle is complicated, too. Reading the Chronicle, past and present, can provide an open window into the city. The paper had a column, many years ago, called “Notes Among the Colored People.” A treasure trove.

The publisher of the paper, for decades, was a man named William S. Morris III. He’s a longtime Augusta National member and, for the tournament, the members often have assignments that are at least tangentially related to their day jobs. For years, Billy Morris would drive players in a golf cart to the Press Building for post-round interviews. He is the moderator for interviews, too. As publisher of the Chronicle, Morris was not, at all, an active or consistent voice for civil rights. But he, like his namesake publisher-father before him, has been a longtime supporter of Paine College, a Black school in Augusta with a rich history and limited resources. There’s Augusta for you.

Many of Augusta’s schools that are integrated on paper remain stubbornly segregated. Many of the churches, the Black churches especially, are segregated by choice. But there are also many places that are far more integrated than they have ever been. The Waffle House at 2951 Washington Road, about two miles from Augusta National’s main entrance, comes to mind. There’s Augusta for you, Part II. It’s a thousand-part series.

I’ve probably made three dozen trips to Augusta over the past 30 years. Here’s one thing I’ve come to know for sure: it’s the damnedest place. It really is.

On a few mornings during this year’s Masters, and on some other mornings during my elongated stay, I went for long, slow jogs, stopping as the mood struck me. As an accidental tourist over the years, I have found that driving aimlessly is a good way to see the sights, and that biking is better but nothing beats being on foot.

Without any plan to wind up there, one run took me into hilly Westover Memorial Cemetery, on Berckmans Road, near Augusta National. A beloved Augusta National caddie, Freddie Robertson, was buried at Westover late last year. I could see, as I started traversing the cemetery’s boulevards, broad stretches of Augusta Country Club. Westover is on the same rolling terrain that made both the Country Club and the Country Club’s neighbor, Augusta National, so well-suited to golf. The Westover land would have made for a fine course, too.

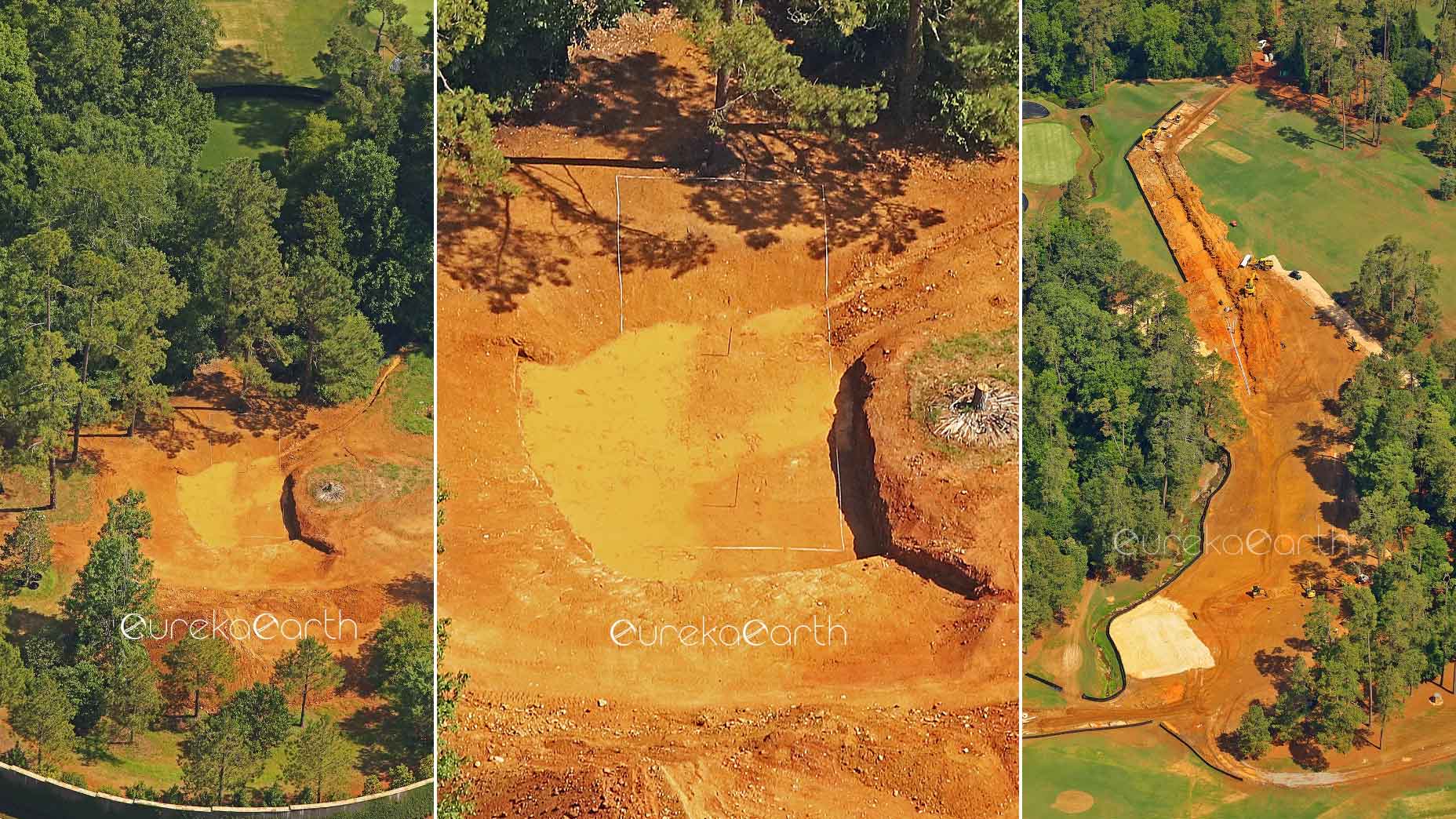

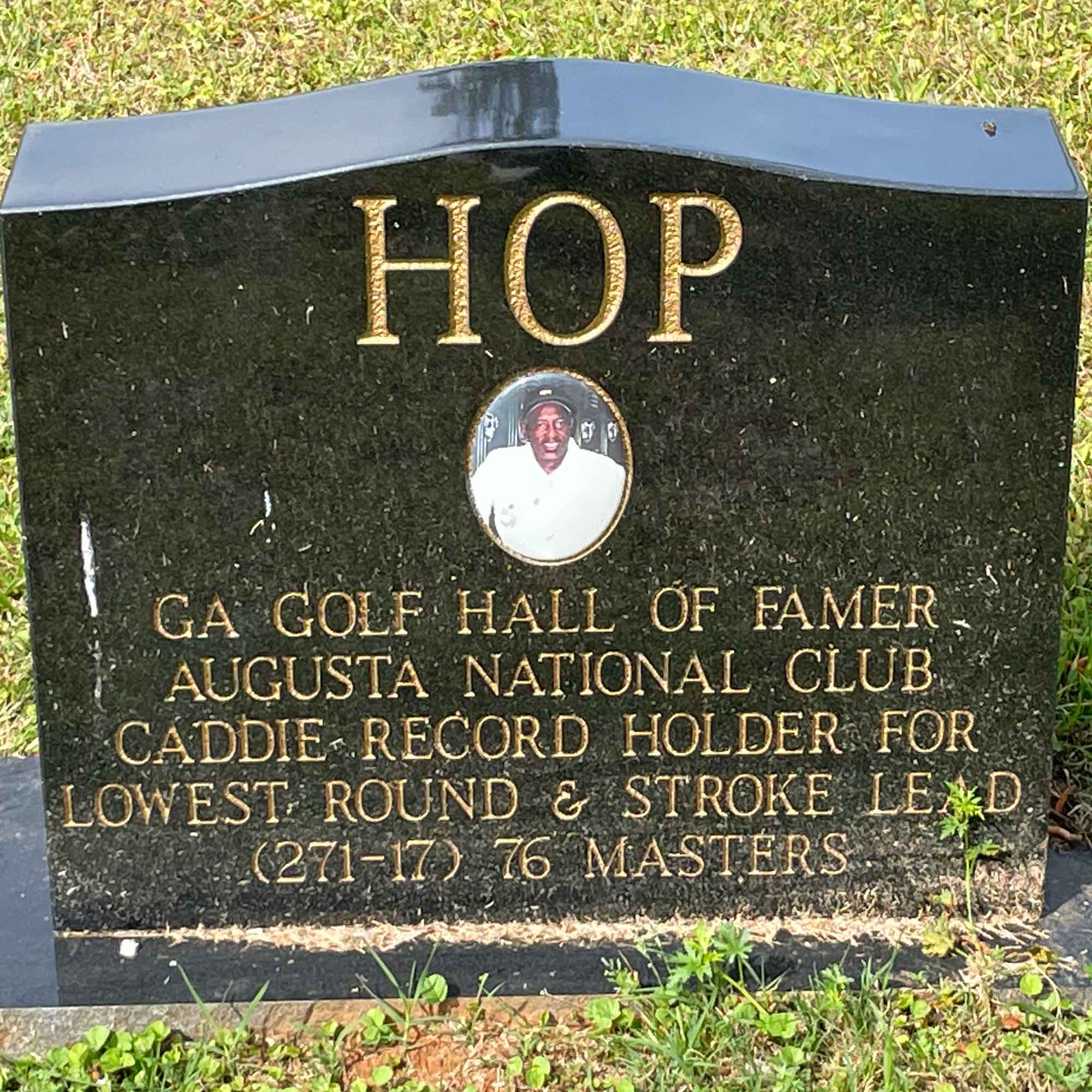

I saw two tombstones there that would bring any jogging golfer to a stop. One had the name SATCHER on one side with a detailed depiction of Augusta National’s 12th hole, in full bloom, on the other. The other belonged Fred “Hop” Harrison Jr., who lies below a shiny, black-granite tombstone. Embedded on one side of the tombstone is a color oval photo showing Mr. Harrison in a suit-jacket and tie while wearing a fedora at a distinctive angle. On the other, a matching oval shows him in his Augusta National jumpsuit. Hop was on the bag when Raymond Floyd won the 1976 Masters, the last one Cliff Roberts presided over. In those days, all the players took Augusta National caddies. The club required it.

From Westover, I continued on Berckmans Road, downhill, in the direction of Washington Road, trotting past Augusta National’s immense grass-field parking lots. To create them, the club bought and flattened nearly every house—but not every last house—that had been part of a post-World War II suburban-style development. Now the spectators get free parking in a bucolic setting, while the club bought itself more of a buffer from the outside world. But it has all come at a cost.

Near the intersection of Berckmans Road and Stanley Drive, surrounded by nothing, you see a modest, suburban-style house. The club owns scores of buildings and they come in every possible shape, so if you take a quick look at the unassuming house at 1112 Stanley Drive, you might think it’s the club’s Lost & Found center, something like that. But it’s actually a three-bedroom brick home owned by Elizabeth and Herman Thacker, both well past 80. They’ve lived there for decades and they wouldn’t sell it. It was in that house that they raised their grandson, a boy named Scott Brown. Now that grandson is a 37-year-old card-carrying member of the PGA Tour. What are the chances of that?

Scott Brown has not played in the Masters. Not yet. Last year, at Riviera, he finished two shots behind the winner, Adam Scott. He misses a lot of cuts but he’s very good at golf. He’s good enough to dream.

Imagine his drive to work, if he got in the Masters and stayed with his grandparents. Stanley to Berckmans, make a right. Berckmans to Washington, make a right. Washington to Magnolia Lane, make a right. Not even a mile, grandma’s kitchen to player parking. One win would do it, as long as it’s the right one.

That route is not ideal for jogging, and it’s not meant to be, not on the south side of Washington Road, anyway, the golf-course side of the road. The sidewalk starts and stops, for one thing. Also, there’s nothing really to see, except a long line of trees and shrubs and walls interrupted by gates and security huts. Still, there’s something thrilling about the whole thing. On the other side of all that fencing, natural and otherwise, there’s a course and a club and, one week a year, a sporting event that draws interest from all over the world. Plus, all those foodstuffs. People want in.

It’s a straight shot down Washington Road — on foot, on bike, in a car, on a bus — from Augusta National to downtown, to Harrisburg and Laney Walker, the neighborhoods that the club is committed to helping.

Harrisburg, settled as a mill town, is an old name but Laney Walker is a more recent invention, combining the names of two extraordinary Augusta figures, Lucy Craft Laney, an educator, and Charles T. Walker, a minister. The Rev. Walker was born into slavery and became the founder of Tabernacle Baptist Church, a spiritual and civic center for Blacks in Augusta. When Leon Maben refers to Lucy Craft Laney, who died in 1933, it is always as Miss Laney. That’s how his parents referred to her. Reverend Walker is Reverend Walker.

Leon gave me a tour of the Lucy Craft Laney Museum. Across the street from it is Laney High. Miss Laney is buried on the school’s property. Jim Dent went to Laney High. So did the opera star Jessye Norman. From the museum, we drove to the Cedar Grove Cemetery. Yes, you’re now back at the start line: It’s a warm April afternoon and the name WIGFALL, etched in stone, is about to appear, right over Leon’s right shoulder.

Leon was a terrific guide. He pointed out the tombstone marking the grave of a 19th-century woman named Amanda America Dickson Toomer and told me about her. As Amanda Dickson, she was born into slavery in 1849, under circumstances too painful to describe here. When she died in 1893, she was a millionaire without a will. A different kind of tragedy. Her life was more dramatic than any single TV movie could capture. Still, one was made, starring Jennifer Beals.

Leon showed me the grave marker for Willie Peterson, Jack Nicklaus’ longtime Augusta National caddie. Mr. Peterson lived large in Augusta but died quietly in New York City. Sixty-six, lung cancer. In death he made one final trip home. His flat, horizontal marker, which arrived at Cedar Grove more than 20 years after he did, depicts a caddie in outline, wearing an Augusta National jumpsuit, with this inscription:

Willie Peterson Jr.

1932-1999

Caddie for Jack Nicklaus

1963-1965-1966-1972-1975

MASTERS TOURNAMENT

Those are the years Big Jack won his first five Masters. Starting in 1983, the club allowed the players to bring their own caddies to the tournament. In 1986, when Nicklaus won his sixth, at age 46, his eldest son was his caddie.

We walked over to Leon’s father’s gravesite and Leon noted high grass in the vicinity of Noy Maben’s final resting place. Leon does a lot of minor cemetery maintenance himself, but this job required a lawn mower. The cemetery is owned by the city and its manager is an acquaintance of Leon’s. “I’ll give Reggie a call,” Leon said.

Noy Maben — who, with his wife, adopted Leon as a baby — had a barbershop in downtown Augusta that was a short walk from the family home. There were still many first-generation freemen and freewomen alive when Noy Maben was born in 1894. By the time Mr. Maben died in 1975, Henry Aaron of the Atlanta Braves had replaced Babe Ruth as baseball’s all-time home-run leader. A Black man had replaced the Great Bambino as the owner of the pastime’s most glamorous record. Leon and his father watched baseball whenever they could.

As a boy and teenager, Leon logged many days in his father’s shop, shining shoes and brushing hair clippings off the shoulders of his father’s customers. He listened to the men talk about baseball and football, religion and politics, wives and women. Golf didn’t come up much, Augusta National even less, the Masters barely at all.

Golf was for the folks in Sand Hills. They worked in golf, as caddies, but also as drivers, waiters, housekeepers and bakers. Some of them played the nearby city-owned course, The Patch, after it became open to Blacks. (The course dates to 1928 but it became open to Black golfers only in 1964, by court order.) Sand Hills liked golf. Downtown Augusta had football and baseball and basketball. Downtown Augusta had its own Black ecosystem, and the barber shop was an important part of it. Downtown was where you found the real action.

But that didn’t stop Leon from trying to date a girl from Sand Hills “with a mean daddy” while in high school, or trying to get work at the Masters. Each year, in late winter, Augusta National would announce that the club was looking for local kids to work the tournament, picking up wrappers and sweeping the porches, and twice in the late 1960s Leon heeded the call. At the appointed time, Leon and 20 or so other kids gathered outside the gates of the club. A club manager sized up the pool. Leon did not get picked, not the first year, not the second. “Guess I was too scrawny,” he told me.

All through school, Leon was young for his class. He turned 17 in February 1970, when he was a senior at T.W. Josey, one of two all-Black high schools in Augusta then. He was working at a McDonald’s on Walton Way, a mile or so from his house, so he didn’t try to get a job at the Masters that year. He was trying to get a scholarship to play college baseball. He was helping out in his father’s barbershop. There was homework and church, dating and hanging.

So he most decidedly was not paying attention to the Masters of 1970, the year Billy Casper and Gene Littler finished in a tie through 72 holes. Josey High, closed for Masters week, was back in session on the Monday, when Casper handily won the 18-hole playoff. Leon was more likely to know, seven games into the new baseball season, that Hank Aaron was batting .462.

One month later came an event that changed Leon’s life, and life in Augusta: the Augusta Races Riots of 1970. This is how NPR summarized it on its 50th anniversary:

“The story is all too familiar: a Black teenager suspiciously dies in a county jail. Law enforcement’s explanation of what happened doesn’t line up with the boy’s injuries. In response, people protest in the streets and violence erupts. These events didn’t happen last month. They happened in 1970 in Augusta. For two days, starting on May 11, 1,000 Black residents rebelled against the city’s systemic oppression. More than 100 blocks of neighborhoods and businesses — about seven miles — were ransacked and vandalized. Police killed six Black men.”

Leon Maben was working at the Walton Way McDonald’s when would-be rioters stormed in. They saw Leon, asked him if he was OK and turned around. His father’s barbershop was spared, too. But Leon has carried the terror and the heartache of those two days ever since. By his accounting, 100 Black-owned businesses in the Laney Walker business district were looted by Black residents, many of whom were desperate and angry long before the boy’s death in the county jail. But that death was the tipping point. The tragedy of it all is incomprehensible. It was years in the making.

As Leon and others see it, the Black business community in Augusta never recovered. Augusta National’s newest and biggest philanthropic effort, the one that Fred Ridley announced last November, aims to change that. The club wants to be part of Laney Walker’s renaissance. Leon Maben has devoted himself to the same thing. For the first time in his life, he’ll tell you, he’s rooting for Augusta National. Their interests align.

We left Cedar Grove, Leon in the passenger seat of my green Mini, with its Pennsylvania plates, the windows down and the sunroof open. I didn’t tell him — there was no reason to — about the hours I had spent in a different Cedar Grove cemetery, in Suffolk County, on Long Island.

Behind my boyhood home was a little woods with narrow paths. The longtime mayor of our village lived in a big house with that woods on one side and a murky cove on the other, a tributary of Patchogue Lake. Mayor Waldbauer’s house fronted narrow Cedar Grove Avenue, with an old cemetery across the street. As kids, in the 1960s and ’70s, we’d ride bikes in the cemetery, now and again, and occasionally watch the gravediggers at work. The Patchogue Library was just down the street, as were the offices of George Waldbauer & Son. Across the street was a bowling alley, Maggio’s, and next to Maggio’s was the Deli King, which fronted Main Street. On Main Street you could catch a bus to Bellport, one town east, where there was a village-owned golf course. Uh-oh. I better get off right here.

Leon seemed to be in no rush to go anywhere. We were driving on Laney Walker Boulevard Extension when he asked, “Have you ever seen a real plantation?”

“I haven’t,” I said, not knowing quite what he meant.

“Would you like to?”

“I would.”

He pointed us out of Augusta and over the Savannah River via the Sand Bar Ferry Road Bridge. We entered South Carolina.

What, I asked Leon, is the name of the plantation.

“Redcliffe,” he said.

My head did a double-take shake.

I have known the name Redcliffe Plantation for years. I knew it was in South Carolina. I never knew it was not even 10 miles from downtown Augusta.

My parents had close friends in Bellport, Ed and Carol Bleser. Dr. (Mrs.) Bleser was a university historian. She published a book in 1981 called The Hammonds of Redcliffe. I recall, vividly, being a senior in college, thumbing through the pages of The New York Times on a Sunday, and stumbling upon a review of it. I was in awe: somebody I knew had written a book that was reviewed in the Times. It was one of the things that set me on the path that I’m trying to stay on today.

When we got to Redcliffe, a vast state tourist site, the gates were closing, but Leon knew the woman in charge and she let us in. (Of course.) Redcliffe had, and has, an old, narrow entranceway called Magnolia Alleé that Leon said was the inspiration for Magnolia Lane. (Of course.) In the posted historical literature at the Redcliffe mansion, I read about slaves the Hammonds owned, the Wigfalls. (Of course.) One of the emancipated Wigfalls later opened a grocery store in Augusta.

Back in the 21st century, Leon and I treated ourselves to McDonald’s French fries and iced tea. That’s not quite accurate, the treating part. The car in front of us picked up our tab, anonymously. I have no idea why.

We headed over the Savannah River and returned to Augusta. We visited a man Leon knew who lived in a luxurious house deep in a woods, a man with deep ties to Augusta. He was interesting. Leon introduced me to our host as “my friend Mike.” It was nice. Bobby Jones once said, “There are two very important words in the English language that are very much misused and abused. They are friend and friendship.” I try not to use friend casually. As for Leon, I don’t know. Our host’s grandfather knew Bob Jones well. Cliff Roberts, too. The proof was on the walls. Out came a bottle of wine.

At 9 p.m., Leon and I slipped into TBonz, the steakhouse on Washington Road, just as it was closing. It’s not my kind of place, but it was late and we were nearby. The staff could not have been more accommodating, but Leon didn’t seem, to me, quite comfortable. He told me later he had been to TBonz three times in his life and each time he was the only Black man in the place.

We both ordered fish. Leon bowed his head in prayer before dinner, the brim of his baseball cap pointing toward his plate. We ate quickly, in deference to the hour and to the staff.

I drove Leon home and on our way there we passed by Augusta National’s main entrance and the grass strip where Leon and the other kids had gathered, more than 50 years ago, looking for work.

Much earlier, when we were still at Cedar Grove, Leon shared his Augusta mystery, his equivalent to my thing about who (if anyone) assisted Cliff Roberts with his suicide. Leon told me about an old church in downtown Augusta, founded by English settlers, decades before the Revolutionary War. The church, St. Paul’s, had a cemetery, a section of which was reserved for slaves. Years later, some of those bodies were exhumed and moved to Cedar Grove. But others were not.

“Who were they?” Leon asked of those left behind. “Who were those people?”

The day after the visit to Cedar Grove, I was stopped at a red light in downtown Augusta. It was another beautiful spring afternoon and I was thinking about hitting balls. My windows were down and so were those of the car idling to my right. And there, by pure chance, was Leon.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com