FORT WORTH, Texas — Seventy-two-year-old Devoyd Jennings watched the final-round telecast of the Charles Schwab Challenge with great interest on Sunday afternoon. In his nearly three decades as a Colonial Country Club member, Jennings had never seen a black golfer contend this deep into the weekend at the fabled PGA Tour event at his club. And now here was Harold Varner III, an amiable 29-year-old by way of Gastonia, N.C., in the hunt.

Varner’s fine play had landed him in the fourth-to-last pairing Sunday and just one stroke behind leader Xander Schauffele. Making Varner’s performance all the more riveting was that it had unfolded against the backdrop of the racial and social unrest that has rocked the nation.

As you likely know by now, a fairytale ending for Varner wasn’t to be. After a quiet even-par front nine, he came home with two bogeys and seven pars to finish at two over for the day, dropping him into a tie for 19th. Still, Jennings remained captivated by Varner, for good reason.

Twenty-nine years ago, Jennings was part of the first wave of black members — a half dozen in all — that Colonial admitted. This came just months after the PGA Tour enacted a policy that forced tournament host venues with all-white memberships to take “appropriate action” to be more inclusive.

So, for Jennings, seeing a black golfer win a PGA Tour title at a club that Jennings helped diversify would have been especially meaningful.

“If he had won, it would have been sweet, it would have been the fulfillment of the dream we had when we joined,” Jennings said Sunday in an interview at his home, just minutes from Colonial. He was in his living room, the TV tuned to CBS, and wearing a white sweater baring the Colonial logo. “We wanted to make a difference and bring others into the game. A win would have meant the dream had been fulfilled. It didn’t happen today, but the dream is still alive to bring others into this great game.

“Man, if Harold had done it today, I would have been shouting for a month, but we’re still going to claim this.”

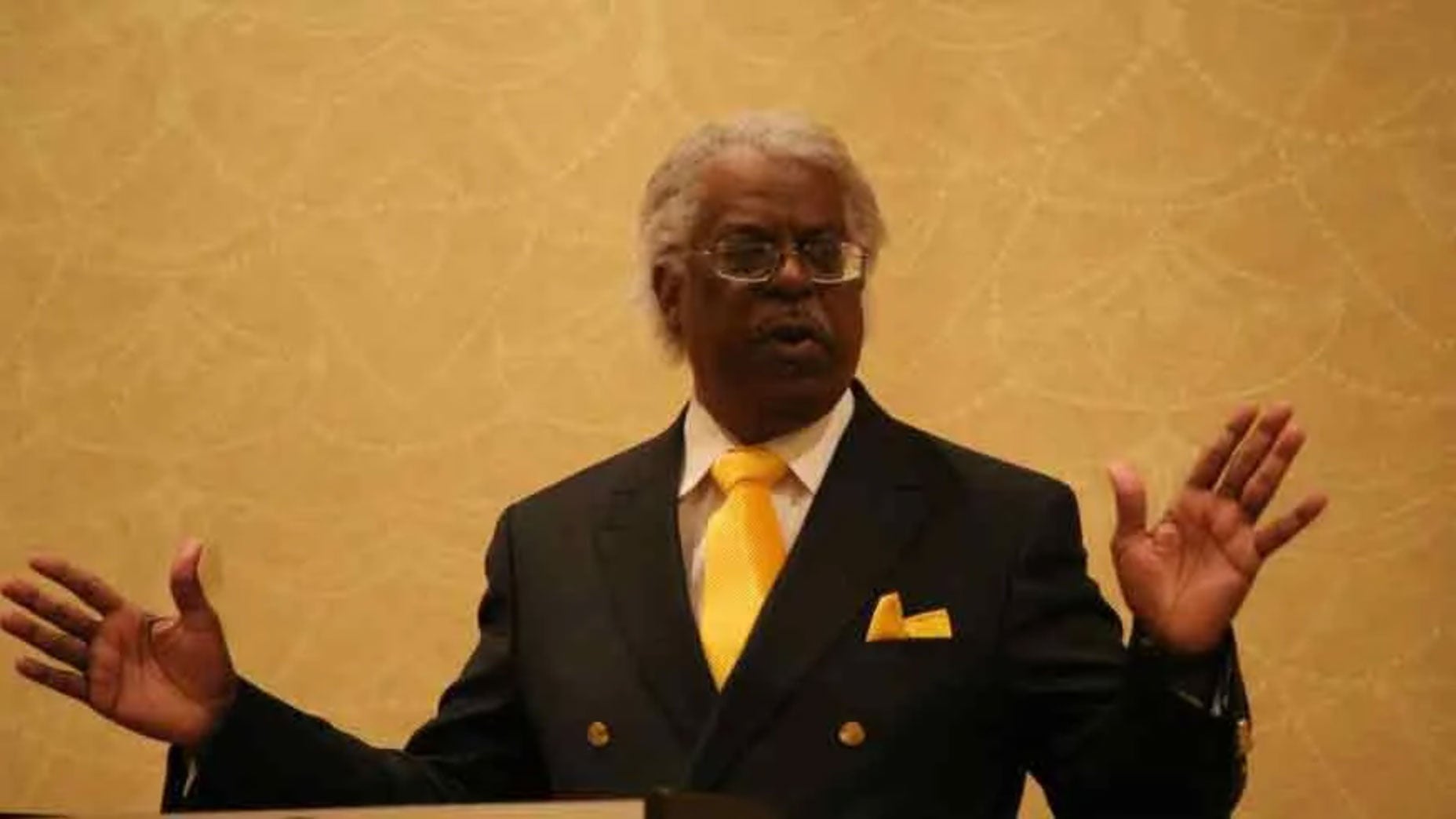

Jennings is the president and CEO of the Fort Worth Metro Black Chamber of Commerce. His company, which supports minority-owned businesses in the area, holds its annual fundraising tournament at Colonial in the spring, a scholarship dinner in the fall and a “gift show” for women members. Jennings, who’s known as “J” at the club, said he has also tried to impart some of his heritage to his fellow members.

“I go to the bar and they say, ‘J, what have you got going now? What’s next for you?’” Jennings said. “I’ve brought in speakers and African crafts and books and things for the gift show they have never seen. It’s a way to connect [members] where we weren’t connected.”

Jennings said the club has helped him and his wife Gwen connect with people he otherwise would never have met; it’s also a useful networking tool for his colleagues. “I didn’t grow up in a country club setting and most people in the minority community didn’t,” he said. “But when they see [the club] and see the business connections you can make here, it’s helpful.” But Jennings also said that he feels Colonial still needs to further evolve. The lack of young black members, he said, troubles him.

“When we joined in 1991, it was a breakthrough moment because we had never been allowed here, but it needs to accelerate,” he said. “Now the majority community has a chance to mentor the minority community and bring somebody into the club like somebody brought me in.

“There are businessmen in Fort Worth right now who can mentor a minority community member and bring them into the club. Show them what country club life is like. That can be done nationwide. With the minority community, you are going to need to come get us.”

Jennings also has a message for Varner, for whom he gained much admiration over the last four days: “Harold should approach the players on the PGA Tour. Players who already know him and say, Who can you mentor? Who can you bring into golf? Somebody brought him in — who can you bring?”

When he was a younger and played more regularly, Jennings said he would invite two or three young minority golfers to the club and pair them up for a round with some of Colonial’s better players, with the goal of getting his guests hooked on the game. And to this day, he said, he still uses the club as a means to develop young minds. Every year he brings the Black Chamber of Commerce Young Leadership class to Colonial to teach them business and social fellowship.

The way Jennings sees it, he’s just paying his good fortune forward.

“I had three people help me out when I got started with golf. I just want to help others,” he said. “That’s something we can all do.”