Dave Stockton Jr., former PGA Tour pro and son of the legendary short-game guru, wanted a putting green in his backyard in Rancho Mirage, Calif. His reasons weren’t purely golf related: He was tired of his ever-increasing water bill.

But his standards for the synthetic putting green were high. It had to roll like a real one. He also knew what he didn’t want — a concrete slab that didn’t respond like any putting green he’d played in his decade on Tour.

What he got, he says, “looked perfect year-round, even when the dogs went to the bathroom on it.”

Dogs aside, it was a breeze to maintain compared to a real lawn. “Once or twice a year, I had guys come out,” he says. “It was a couple of hours and they were done.”

Stockton liked the green so much that he started working for the company, Back Nine Greens.

Putting greens got a pandemic boost. Stuck at home, people began dreaming about installing a green or short-game practice area. But in the annals of DIY projects, it turns out these greens are tough to create. Engineering a synthetic green is not all that different from creating a real one. It requires drainage, proper pitch and someone who can lay the sod so it doesn’t look like bad plastic surgery. People who try to do it on the cheap can end up with lumpy, uneven and wet greens. Same is true for those who go with real sod. Jack Nicklaus threw in the towel a few years ago and opted for a synthetic green at his home at The Bear’s Club, in Jupiter, Fla. And he owns his own golf course design firm!

“He had a natural green, but with bentgrass he had to cut it every day,” says Bob Hambrick, director of operations at Southwest Greens, who replaced Nicklaus’ green. The Golden Bear ultimately became a consultant to the company and helped improve not only its product’s roll but also its receptivity to shots from up to 200 yards away.

“Our greens are going to do whatever a natural green will do,” Hambrick says. The secret is a sand base. The average cost for these backyard Shangri-las is hard to capture. The synthetic turf goes for around $23 per square foot, cheaper in areas like Arizona and more expensive in places like New York and California. The average green is about 800 square feet, so you’re looking at $19,000 for the turf alone. The challenge — and the added expense — is in getting someone who knows how to shape the contours properly and seam the green so it rolls true.

Steve White, founder of Georgia-based Tour Greens and a former Clemson golfer who still sports a plus-1 handicap, has created a series of ready-made greens that people can buy and install for a fraction of the cost of fully customized greens. The company’s two most popular options are The Southampton ($5,375 for a taste of Shinnecock Hills) and The Carolina ($3,450 for a hint of Pinehurst).

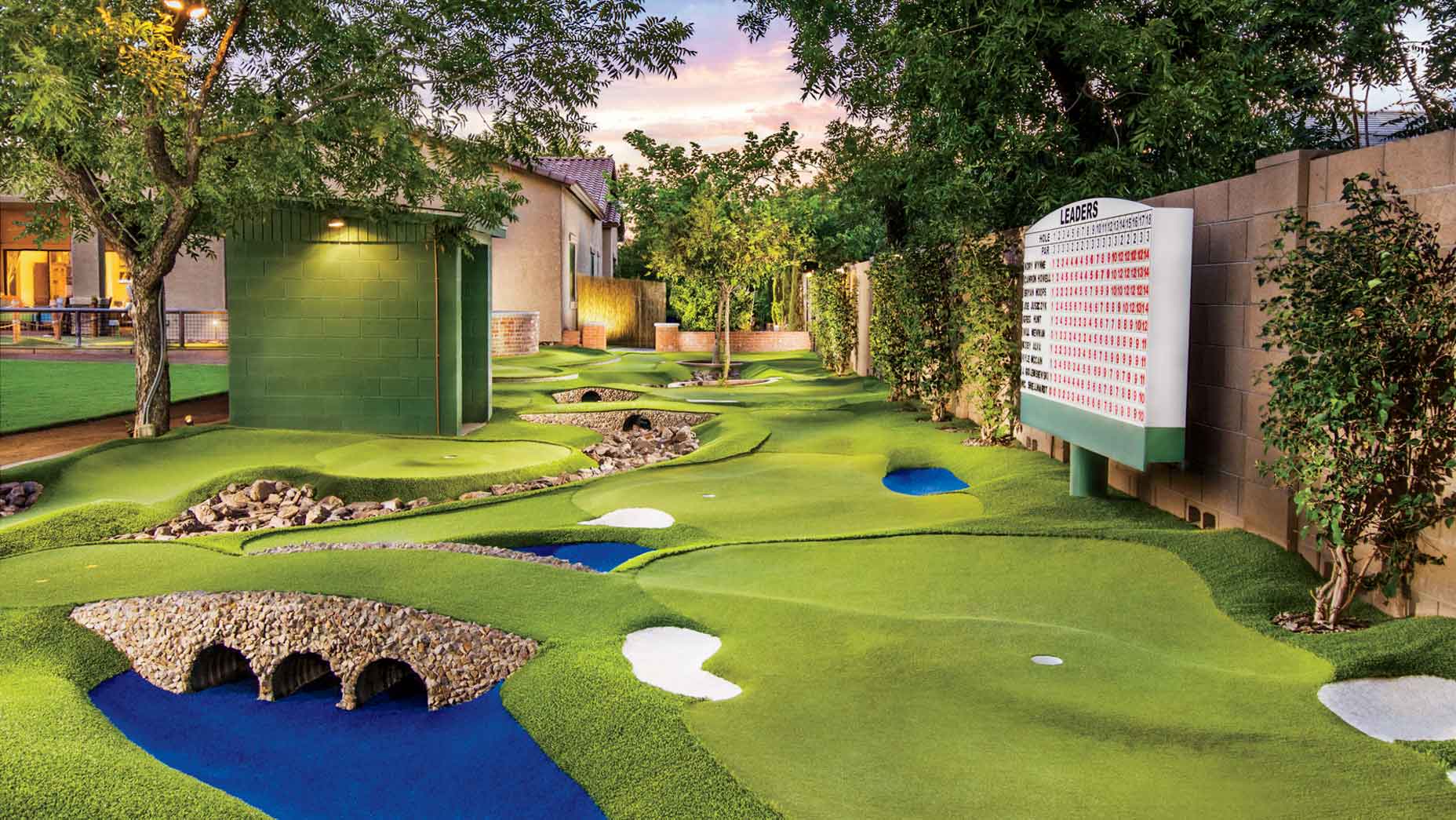

The company also does customized greens, which run from $20,000 to $250,000. Its most popular request is the 12th hole at Augusta National. “To make it look like it’s not just a silly little miniature thing, it could cost up to $200,000,” White says. “The green itself is only 3,500 to 4,000 square feet, but there are bunkers and rough, so the footprint is bigger.”

The annual maintenance for any of these synthetic setups is small. Stockton equates it to buying solar panels — a large up-front cost that you recoup over the years in lawn-care savings.

If there were a gold medal awarded to a home practice area not belonging to pros like Tiger and Phil, it would go to Jim Nantz, the CBS broadcaster and voice of The Masters. In the backyard of his Pebble Beach home, he has recreated the course’s iconic par-3 7th hole.

Nick Faldo, his broadcast partner and a six-time major winner, has aced Nantz’s 7th, as have a cadre of other pros. But not everyone Nantz invites over hits it pure, so he requires visitors to tee up a limited-flight golf ball, which travels a third the distance but, more importantly, won’t break windows.

Dominic Nappi, whose company, Back Nine Greens, designed a practice paradise in L.A. for actor Mark Wahlberg and recently redid Nantz’s setup, calls what he does golf art. “Your apron, your rough, your green — you want it to blend into the landscape of the yard,” Nappi says.

Of course, some people’s backyard practice areas are more extensive than others. Take the deep-pocketed real estate developer in Ponte Vedra Beach, Fla., who hired Bobby Weed, architect of Michael Jordan’s Grove XXIII, to design his practice area on a half-acre yard against the Atlantic. Weed had been charged with renovating the nearby Ocean Course, so it was easy to oblige.

“We had all of our equipment there,” says Joey Graziani, a design associate with Bobby Weed Golf Design. “In the evenings, when we were done with our Ocean Course work, we just went across the street. Our client was a good friend of Bobby’s, so it was just fun for us.”

What they did on that lot is something akin to a mini-mini-mini-Seminole.

They put in bunkers, plenty of pitching areas and two greens — one for putting, the other to receive shots. “You’re trying to create as many different shot possibilities as you can,” Graziani says.

At the same time, simple is better, in both slope and green speed. “You can overcook these things and they’re not functional,” Graziani says. “You could put in some great ridges and slopes, but if you’re trying to work on your game they’re not going to help.”

David Parks, a lawyer who works in real estate, bought a house on New York’s Hudson River during the pandemic. A putting green was high on his list of upgrades. He sees its three holes as a Welcome sign to his new home — albeit a $30,000 Welcome sign.

Has it made Parks, an 8.7 index, a better putter on the real deal — an actual golf course? He believes it has.

“I was in a money game and one down on all the bets on 18,” he says. “I had hit this shot to four feet from 185 yards. I took my deep breath and knocked in my birdie putt.”

Want Paul Sullivan’s advice on all things golf-related in personal finance? Send your questions to moneymailbag@golf.com.