“I called him Pap from the beginning,” wrote Arnold Palmer in his 1999 autobiography, A Golfer’s Life. You can trace the King’s mastery of social skills and his love of people to his mother, Doris, but Palmer’s mental and physical strength, his black-and-white distinctions between right and wrong and his doggedness in pursuit of a goal are directly descended from his father, Milfred, who was best known by his nickname, Deacon, or more commonly, Deke.

Understanding this relationship is the key to understanding what drove Arnie. Two incidents from when he was 3 help explain and define the intense father-son bond. The first occurred when the boy King was carrying a quart of milk up the stairs of his grandmother’s house, and he stumbled and fell on the bottle. The glass shattered and severely sliced Arnie’s left hand. He remembered the doctor stitching him up. “I suspect I may have cried—though perhaps not,” he wrote. “It certainly wouldn’t surprise me if I didn’t, because even then I knew my father and grandfather were tough and seemingly unsentimental men, and I instinctively knew I wanted to be like them.”

MORE: Buy Sports Illustrated’s Arnold Palmer Commemorative

The toddler already grasped the importance of fortitude. His father gave him a grip to match. “He put my hands on the club and said, “That’s the way you hold it,”” recalled Arnie. “He said it just once, but that was enough. I have held it that way from then on. I wouldn’t have dared change for fear he would have caught me. When he said do it, I did it.”

From there, Pap’s advice to his son was straightforward. “Hit it hard, boy. Go find it and hit it hard again.” And that’s all the kid wanted to do: play golf and hit it hard. Doing so, however, wasn’t so easy.

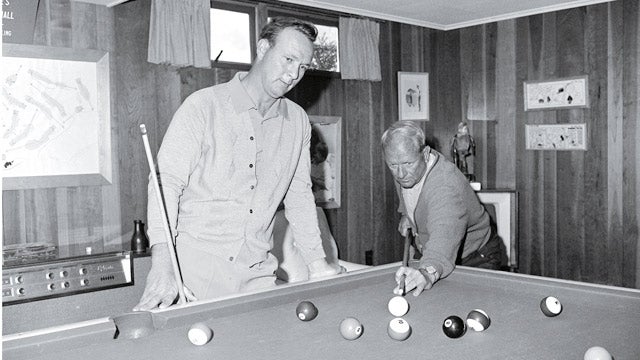

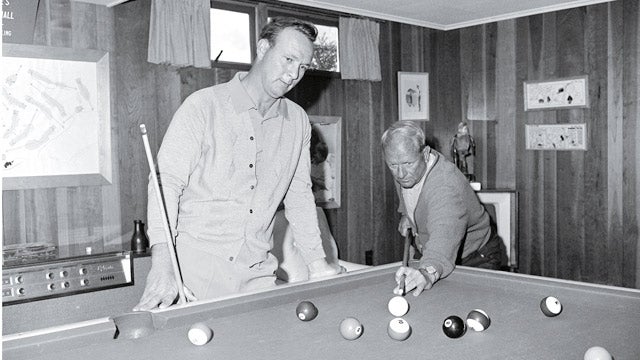

Deke Palmer was the head professional and superintendent at the private Latrobe Country Club in western Pennsylvania. He hewed to the old Scottish tradition that pros and members didn’t mix. That certainly held true for the pro’s family. Young Arnie couldn’t use the club’s swimming pool, and golf privileges were limited to quite early or late in the day. Only rarely did he get to play with his dad. And as with many fathers of that generation, Pap was stingy with praise for his son. He instructed him to obey the rules, to cherish the game and its inherent sportsmanship and etiquette, and to maintain a sensible attitude about winning and losing. What Pap didn’t instill was much positive reinforcement, something that young Arnie craved—and that drove him to succeed.

Everything turned at the 1954 U.S. Amateur at the Country Club of Detroit. At age 24, Arnie reached the final against Bob Sweeny, a well-liked, 43-year-old, silver-spooned dandy who’d captured the British Amateur 17 years earlier. From the wrong side of the tracks came hard-swinging, hardscrabble Arnold Palmer. Two down after the first of two rounds, Pap’s boy roared back, and after Sweeny hit an errant drive on the 36th and final hole, Arnie was a winner.

“As the media swarmed around us, my mother was the first one to hug me when I walked off the final green,” he wrote in A Golfer’s Life. “As we embraced, she was crying tears of joy. “Where’s my father?” I called out. “Let’s get Pap in here. He’s the man who really won the U.S. National Amateur.” For several moments I couldn’t find him in the crowd, but suddenly he was there, quietly smiling for the first time that week. I could tell he was happy. As a flurry of cameras clicked around us, he put his hand on my shoulder and squeezed it. “You did pretty good, boy,” he said simply, and my heart swelled nearly to the breaking point. This meant the world to me, and I felt my own tears coming. I’d finally showed my father that I was the best amateur golfer in America. It was the turning point of my life, and I don’t know if I’ve ever felt as much happiness on a golf course.”

Arnie had pleased his Pap. It’s all he ever wanted to do.