2024 RBC Heritage: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

2024 RBC Heritage: How to watch, TV coverage, streaming info, tee times

Nine dollars, cart included: On the road to Augusta, a stop in rural South Carolina reminds of golf’s allure

It was a small, worn sign, but startling: an arrow pointing left, accompanied by two words in block letters: “COUNTRY CLUB.”

We were driving what I’m tempted to say was an unassuming stretch of road, but the truth is I’d been doing a lot of assuming as the miles and small South Carolina towns along Route 1 ticked by. Shuttered stores and restaurants abutted run-down houses, many of which were being reclaimed by the budding trees behind them, and several shiny Dollar Generals were the only obvious signs of commerce. I’d made plenty of assumptions about the small Carolina towns that looked like time and industry had passed them by.

The “COUNTRY CLUB” sign stuck out particularly given where my copilot/colleague Sean Zak and I had come from (we’d started the morning poking around east coast golf mecca Pinehurst) and where we were headed (Augusta National Golf Club), and it would prove an important reminder of the 99 percent of golf that exists in the in-between.

This was the second day of a road trip that had begun at 6 a.m. in lower Manhattan the morning before and now, just two hours from our destination, we were eager to arrive. Fast food wrappers and empty Monster Energy cans littered the floor by my feet; the latter had started as a joking tribute to Tiger Woods’s energy drink sponsorship, but we’d somehow ended up drinking them unironically throughout the afternoon and were feeling their effects in combination with two No. 1s from Hardee’s.

ADVERTISEMENT

What did a country club look like in Bethune, S.C. (population: 345)? My co-worker, Sean, slammed on the brakes and we ventured some half-mile down Pleasant Hill Road, but there was no golf course to be found. I checked Google Maps; we’d already driven past the waypoint marked as “golf course.” We headed back toward the main road, even more slowly now.

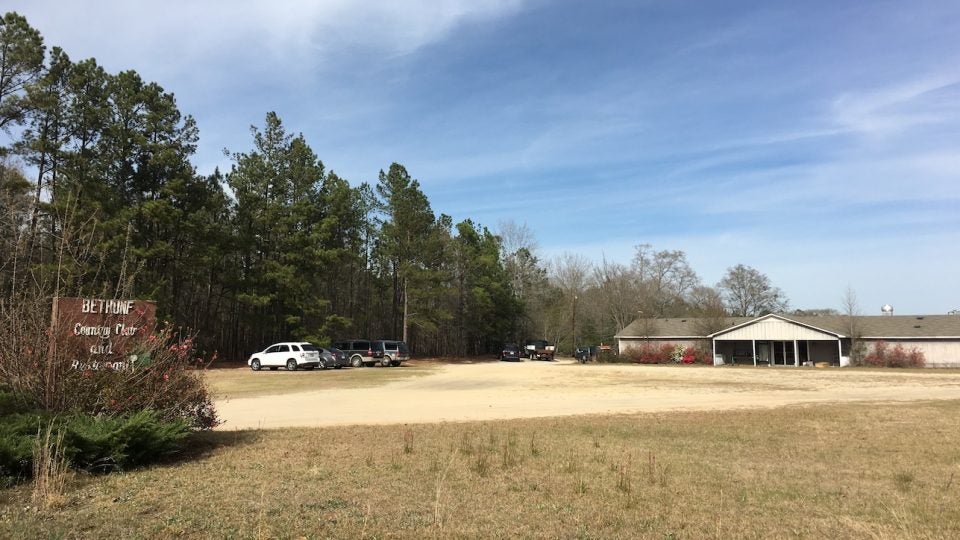

Then, through a thick weave of brambles, a sign: Bethune Country Club. Behind it sat a near-empty dirt parking lot fronting a dilapidated grey one-story building. We’d certainly have dismissed it as another closed business but for one sight: an elderly man tottered across the parking lot in our direction, a thin golf bag slung over his shoulder.

What was this place?

We’d scoured the back roads of New Jersey a day earlier to find the semi-hidden gates of Pine Valley Golf Club, where we were encouraged to kindly remove ourselves from the property. Our excitement here was distinctly different: there, we’d been hoping to catch a look at the highly exclusive No. 1-ranked golf course in the world. Here we’d stumbled on a secret that we might actually be able to play.

We made our way cautiously around the back of the building (the front door was blocked and didn’t seem to open) in search of someone who might quote us a greens fee. Guarding the pro shop was a small fleet of mismatched golf carts, rusted-out lawnmowers and a rules sign that was mostly illegible save for one: “No Carts within 15 feet of Green.” The grounds crew, had there been any, had no lack of equipment to choose from, including a front-end loader sitting next to the sign for the first hole, where a teen in a graphic t-shirt attempted to perch his ball on a tee.

“There’s no way you’ve seen a worse golf course than this one,” Sean murmured.

I’d have ventured no further toward the True Detective-vibed pro shop had I been alone or in the dark, but behind the door we were greeted by a friendly man in a faded red polo. He informed us of the going rate: Nine dollars — cart included. “Cash is good,” he said, then repeated it to himself. “Cash is good.”

He asked the obvious question: What were we doing there? We told him where we were headed.

“Ah, Augusta,” he said. “That’s a different kind of place.”

As we made our way to the first tee, the shop attendant hopped in one of the four-wheelers and went to shoo aside the group ahead of us the way one might a flock of seagulls. “They don’t know how to play golf,” he said, speeding off.

We strapped our bags into the best-looking cart in the fleet, though it still held three mostly-empty packs of cigarettes and a half-dozen soda bottles in the cabin. Then we were off, down the 305-yard downhill par-4 first.

The complete disregard for any sort of course maintenance was impressive, in a way. On the second, a hole sign laid in the woods beside the tee box, which was surfaced (as were all the others) with a ragged dirt-and-moss combo. We discovered by the third that the greens, rather low on actual grass, were actually faster than Pinehurst’s had been that morning. The exception there came from piles of sand that cropped up a couple times per green and brought the ball to a screeching halt. Free relief or in-green bunkering? We weren’t sure.

Several abandoned carts sat ghost-like just off what would have been the 5th fairway, had it been mown (what makes a fairway, anyway?). And the narrow chute from the tee box of the dogleg-right sixth hole called to mind Augusta’s 18th, although a telephone pole and several ominous “WARNING” signs guarded the right side.

The entire place seemed run with a sort of laissez-faire philosophy: things are the way they are and should remain that way.

But we had a terrific time. There was an exploratory aspect to finding the next tee (and choosing where to peg from) and guessing where the next sharp dogleg may lead. Select patches on each green rolled true, allowing for some nifty saves, including a 25-footer that Sean made from the fringe after his tee shot settled between a piece of PVC pipe and pile of old Coke bottles in the woods.

The man in the red shirt was between tractors and the pro shop as we came off the ninth. He nodded with approval when we told him his greens were faster than Pinehurst’s, and reminded us what a good deal we’d gotten. “Can’t do nine dollars with a cart ’round New York City,” he said with a grin.

At his urging, we parked the cart by the first tee: one woman had just arrived and was looking for one that would run well. I thought of warning her that every time we’d hit a big bump, Sean’s bag had ejected out the back, but it felt like that would have been insulting.

I ran inside to grab a Gatorade for the road ($2 — double the price of a beer). I had so many questions left but settled on one: “What’s the course record here?” I asked. After I’d birdied the first, the thought of chasing BCC’s low number had immediately jumped to mind — how many good players could have come through Bethune over the years?

“Twenty-seven,” he said, which meant eight under on the par-35 layout. Holy hell. “Ever hear of a guy named ‘Two Gloves?’ Tommy Gainey? He and his dad grew up playing here.”

The fact that Tommy Two Gloves, PGA Tour winner and small-time golf cult hero, could have been the product of this place made me take a step back. He gestured to a picture in the corner of the shop, tacked on a bulletin board. It was Gainey on a promo for Big Break IV, accompanied by his signature, and a note: “To Bethune C.C. Thanks for everything.”

It stuck with me, the idea of that golf course raising a Tour player with more than $6 million in career earnings, as we got back on Route 1, now less than two hours from Augusta.

“Have a good trip down the river,” the man in the shop told us as we went. I couldn’t figure out what river he might’ve meant, but I liked the sound of it.

Augusta National, which I am about to see for the first time, is a very important golf club. It can also run the risk of being perceived as The Only Golf Club. There are, of course, more Bethunes than there are Augustas; and the more time we spend around the latter we run the risk of forgetting about the former altogether. What we think of as “requirements” of a golf course are rather negotiable, given that the woman who took our cart on Easter Sunday at Bethune will enjoy the same challenge of getting the ball in the hole as Rory McIlroy will this Thursday.

The miles continued by — 35 per hour, if you followed the road signs — as we rolled away from Bethune and through its sister towns, where land was cheap and time passed slow and golf in any form seemed to make plenty of sense.

ADVERTISEMENT