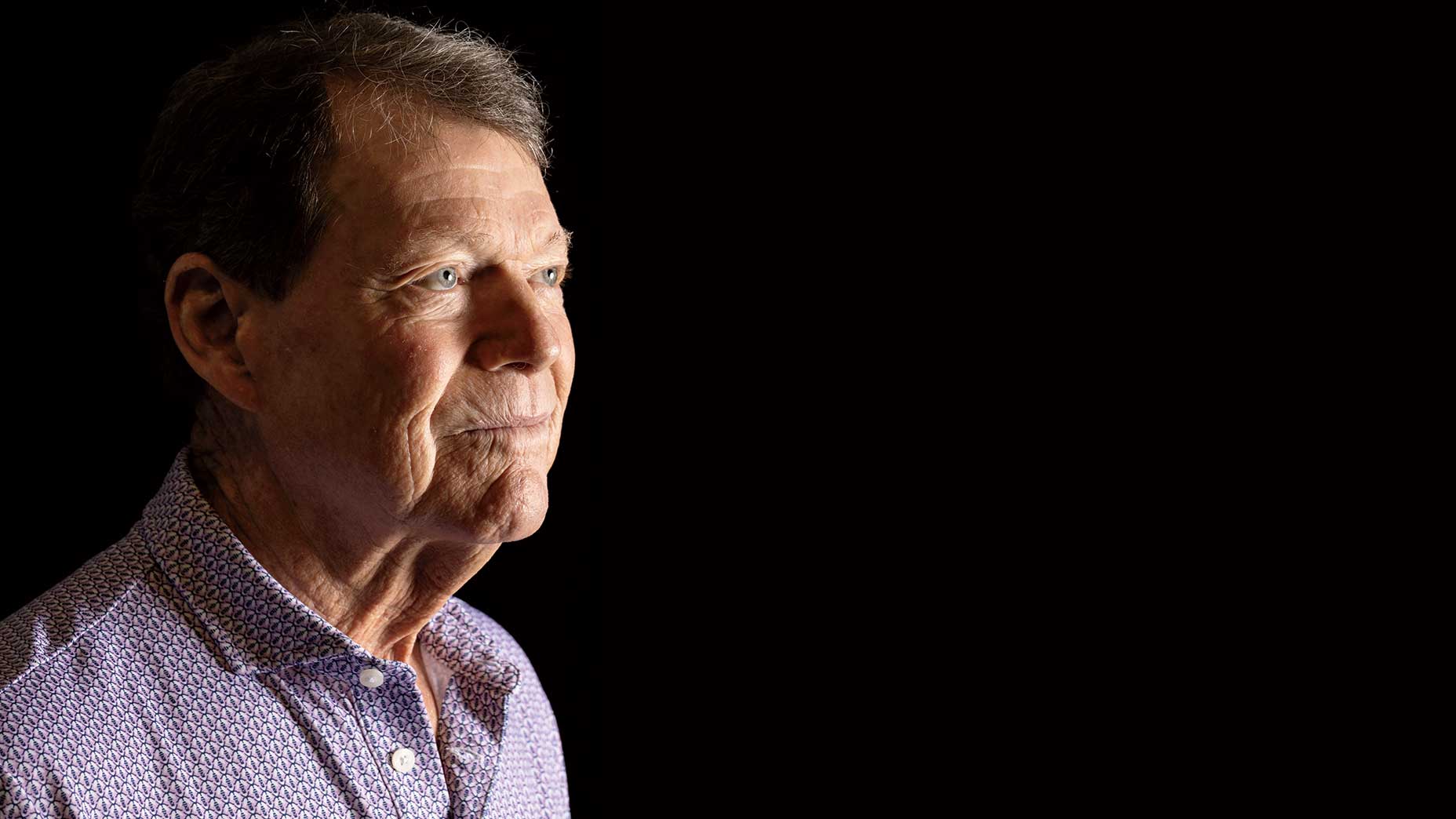

Tom Watson isn’t widely known as a sentimentalist, but, on certain topics, he can sound as wistful as a Hallmark card.

“The possessions that mean the most to me are the photographs,” he says. “The photographs are what evoke the memories.”

It’s a wet midwestern morning, Open Championship weather in Overland Park, Kan., and the greatest American links player of all time is standing in the doorway of his office on the 11th floor of a boxy building in a leafy business park. Rain streaks the windows. Trophies crowd the shelves, so many of them that Watson can’t say without squinting which events they represent. He has no such trouble with the pictures on the wall. Few golf fans would. Many of the images are iconography: Watson chipping in at Pebble to steal the 1982 U.S. Open; Watson walking with Jack Nicklaus, arms around each other’s shoulders, in the gauzy afterglow of their Duel in the Sun.

That was 1977, at Turnberry, site of the second of Watson’s five Open titles and the backdrop of his most famous defeat, when, in 2009, at age 59, he came within a bad bounce of capturing the Claret Jug for what would have been a record-tying sixth time.

Now 73, he cuts a similar profile to that of his prime. The gap-toothed grin. The construction foreman’s forearms. His demeanor is familiar too: cordial but reserved, with a brusqueness toward questions that brush on touchy subjects. Don’t ask him to go deep on his controversial Ryder Cup captaincy in 2014 or the tension with Phil Mickelson that rose around it. Interviews with Watson rarely morph into confessionals. But they cover a lot of ground.

In a Hall-of-Fame career that spanned five decades, Watson won 70 professional tournaments, including eight majors, and earned a reputation as one of golf’s most authoritative voices, as forthright about the game as he was guarded about himself.

Some things he can’t hide. Watson’s eyes still well up when he speaks of his friend and longtime caddie, Bruce Edwards, who died of ALS in 2004, as they do when he mentions his late wife, Hilary, who succumbed to cancer in 2019.

But of his ’09 Open heartache, the near-miss at Turnberry, he says flatly, “I lost.”

Watson gave up competing seven years ago. Like his great rival, Nicklaus, before him, he has become a “ceremonial golfer.” But he hasn’t hit a shot of any kind since April, when, coming off a mishap on his ranch that required shoulder-replacement surgery (more recently, he had another procedure to repair tendon damage in his hand), he helped Nicklaus and Gary Player get the Masters underway.

Still, ceremonial does not mean silent. Watson follows the game closely and has strong views on it. With the 2023 Open Championship approaching, GOLF asked him for his take on everything from the distance debate to the LIV divide, and to share his favorite recollections of his long years on the links.

I’ve got a rich life, but, in the end, I’m a golfer.

GOLF: There were a lot of headlines about your accident, but I never read a detailed play-by-play. What, exactly, happened?

TOM WATSON: Being a grandfather and having a farm and having had go-karts for my kids when they were growing up, I thought, I’ve got to get a go-kart for my grandkids. So I got one, and I built a little track out there. I was going around a corner too fast and I turned it over, and I stuck my arm out to brace myself and I just kind of ruined my shoulder.

Flipping a go-kart. Maybe you’re lucky it wasn’t worse.

Not really. Go-karts have cages, and I had a helmet on. But being a 175-pound guy, I guess I just thought I was strong enough to push a 250-pound cart back over with one arm. Bad idea.

The swing looked good for that ceremonial tee shot at Augusta.

I practiced for that. I was down in Texas, running horses with my trainer and his wife. We play golf together, so I decided to try hitting some shots. I topped the first one and hit the next three thin. But, after that, I managed to stay down on it with a wedge and a 7-iron. Then I grabbed my friend’s wife’s driver, and I hit it pretty good. At Augusta, I was just hoping I wasn’t going to top it, so I teed it up a little higher to make sure I wouldn’t.

In your last few years competing in the Masters, you described yourself as a “ceremonial” golfer, and you didn’t always sound thrilled about it. How do you feel about it now?

I’m honored to be a part of that tradition, but I also have a lot of other things going on in my life. About seven years ago, I decided that my competitive golf career was basically over. At the time, Hilary was doing very well in the cutting-horse world. I followed her around to a few shows, and I thought, You know, I want to try something new. I decided I was going to become the best cutting-horse showman that I could be.

How’s that going? Are you a single digit in that sport yet?

I’m more like a 15. Every now and then, I’ll break 80.

Does it fill a competitive need that you used to satisfy with golf?

People ask me if I get nervous going into the show pen. The only time I really get nervous is when I allow myself to think that I have a good run going. And then it hits me, “Oh, no. That’s exactly what you say when you’re six under on the golf course with six holes to go and you end up four under par.” But I don’t usually get nervous. Maybe because I’m not good enough.

Or maybe it’s because on the course you learned to cope with pressure.

I couldn’t handle the pressure when I first came out on Tour. I wasn’t steeped in it. I’d played amateur golf, and there was pressure there. But playing week in and week out with the pressure of making the cut, that was the first time I’d felt the pressure of trying to make a living. In those days, if you made the 36-hole cut, you were exempt into the next week’s event. You didn’t have to Monday-qualify if you made the cut. So there was big pressure. After that, there’s the pressure of trying to win, and there were times when I had that chance and I couldn’t do it. I wanted to get it over with and I got too fast. Eventually, I learned I had to slow down and breathe. When people ask me about dealing with pressure, that’s what I tell them. You have to keep putting yourself there until you learn enough to get comfortable.

And confident?

There’s a difference between confident and cocky. Byron Nelson said it right. He said, “I never wanted to go to the first tee saying, ‘I’ve got this totally.’” When he was too confident, that’s when he made mistakes. He said he always wanted to have a little bit of doubt about his swing. The kind of doubt we all have.

I’ve heard it said that you first realized you could play with the big boys when you were 15, and you won a big Kansas City amateur match-play event. True?

Actually, I was 14, playing with the men. That was important because it led to other opportunities. But, no, the first time I really believed I could play with the best was ’77 at Turnberry, when I walked off the final green with Jack Nicklaus and he put his arm around me and said, “Tom, I gave you my best shot, but it wasn’t good enough.” Right then and there, I said to myself, “Well, if I can beat the best in the game, then maybe I can play a little.”

Not bad for a guy who didn’t even like links golf at first.

I did not care for it, no.

Do tell.

In 1975, the Open was at Carnoustie, and I was staying with John Mahaffey and Hubert Green. We fly into Edinburgh, rent a car, drop off our stuff and head immediately to the course to play a practice round. The club secretary, Keith Mackenzie, a gruff-looking man with a handlebar mustache, meets us in the parking lot with a big smile on his face and says, “Wonderful to have you here.” He was very gracious. And I said, “Boy, I can’t wait to play the course today.” And Keith’s expression changed. There was a pregnant silence and he said, “Tom, I’m very sorry. But you can’t play the course today. It’s strictly for qualifiers to play today. Not the exempt players.”

Buzzkill.

But he made arrangements for us down the road at Montifieth. We get on the first tee, and everything was raw as a bone. I hit my drive right down the middle. John and Hubert found their balls, but I didn’t find mine. So I dropped another. Then I walked about 40 to 50 yards off to the left, and my ball was in a small depression. I’d hit it down the middle and I wound up there? Not a good first impression. I thought, I don’t think I like this.

And yet you won the Claret Jug that year. What changed in your attitude?

I decided to get off my pity pot, to stop complaining and accept what links golf gives you — that it’s a game on the ground as well as the air. I came to accept it, but I didn’t really enjoy it. That came later.

When?

In 1981, [former USGA president] Sandy Tatum and I went over there before the Open at Sandwich. We were at Dornoch. I remember the starting time: 10 a.m. A beautiful day. Bright sunshine. Halfway through the back nine, it started to cloud up. A reception had been organized for us. We’re inside and it starts to rain. A drip at first, but then the windows start to wash with rain. The bushes are blowing. And I go over to Tatum and I said, “Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” And he says, “I’ll organize the caddies.” So we went out, just the two of us and two caddies. Wind blowing. Rain coming down sideways. On the 16th, I hooked it in the quarry down to the left, hit my third to the front of the green and came trudging up and said, “Tatum, I’ve never had more fun playing golf than right now.”

You think it was fun for your caddies too?

I don’t know. But that was the day I fell in love.

Who impresses you the most among contemporary players?

I really like Rahm and Scheffler. They go at it in different ways. Scottie’s got that upright swing. Jon’s is short, with the bowed wrist—short but powerful. But more than anything, I like how they handle themselves and treat people.

The pros play a different game. And there’s talk of rolling back the ball for them. Thoughts?

A few years ago, when Bryson DeChambeau took it over the water on the 6th at Bay Hill, and the crowd went wild, I thought, That’s really exciting. You can’t mess with the ball. But I’ve changed my mind. For the good of the game, they need to reduce how far the ball goes. What they’ve proposed is to bifurcate, though. I don’t like that. I think everybody ought to play with the same golf ball. For the pros, it would take less than a week to adjust. For the rest of the world, it would take longer. But there are ways, including playing from the right tees. The question then becomes, what happens to the inventory of illegal golf balls? Who is going to bite the economic loss? There’s still a lot to talk about, but I think it needs to happen.

You’ve rarely been shy expressing your opinions. What’s your take on the division in the men’s professional game today? [Eds. note: This interview was conducted before the announced merger of the PGA Tour, DP World Tour and Saudi PIF. Watson has since commented on that as well.]

My take is that money talks, and it bought these LIV players to leave the PGA Tour and violate its conflicting-event rule. That’s what happened, right? And the format for LIV is an exhibition tour versus what I consider competitive golf, where you have a cut. I’ve played exhibition golf. I’ve played a lot of tournaments where I got a guarantee. But, in almost all of them, there was a cut, and I prided myself in making that cut. What I consider pure golf, championship golf, is different.

Sounds like you’re okay with LIV not getting Official World Golf Ranking points.

Here’s my take: What the major championships ought to do is get together and say, You know, these LIV guys can play. We give exemptions to amateurs and other players for different things, so why don’t we give exemptions to the LIV players? Let’s say we give the top five or the top three LIV tour players exemptions into the majors. The real tours can have their World Golf Ranking system. A lot of those LIV guys can really play. They’ve shown that at the majors. I think they ought to have an opportunity to compete. But, when they left to play for money, the PGA Tour had every right to do what it did, and I concur with it.

When you were in your prime, there were talks of “super leagues.”

Don’t I know it. I was approached by [sports agent] Mark McCormack in the late ’70s. I remember him succinctly saying, “We’re going to pay million-dollar purses.” In those days, $200,000 was the total purse in tournaments. He said, “We’re going to take the top 20 or 30 players, and if you’d like to do it …” And I said, “Mark, that would ruin the PGA Tour. It’s not going to work for me.”

Because, essentially, it would create a two-tiered system?

If you take all the top players, what do you have left? That’s something I’m wondering about now for next year’s PGA Tour. How are the sponsors of non-elevated events going to feel? And what about the exempt guys who aren’t in the elevated events? What kind of chance will they have to move up?

I think a lot of people are wondering about those things.

I’m wondering too.

An event that’s not about money is the Ryder Cup. You played on several winning teams and captained a winning team in ’93, the last time the Americans won on non-U.S. soil. But the last time you were captain, in 2014, the U.S. lost, and you got pretty rough treatment in the press. Did you feel that was unfair?

I did what I thought was the right thing to do.

Is there anything you wish you’d done differently?

Bottom line: Their team was better.

Have you had many conversations with your players from that team since?

Sure. They still call me “Cappy.” Jordan Spieth. Every time he sees me, it’s “Hey, Cappy, how you doing, man?”

What about Phil Mickelson? He was pretty critical of you. Have you had conversations with him?

I have had some conversations with him. Sure.

How have those been?

Been great.

Great? Really?

Uh-huh.

I want to ask you about a different relationship: the one you have with David Feherty. You were credited with helping save his life by getting him to address his drinking. Was there a particular moment that prompted you to get involved?

I saw a friend who was having the same issues with alcohol as I had earlier on in my life. I offered my help, and he took me up on the offer.

Was there anyone in your life who helped you in a similar way?

I was blessed with several friends and loved ones who helped me through my affliction.

There’s a story your friend and caddie Bruce Edwards used to tell about the time you hooked a shot on the 18th at Pebble, and, as the ball was headed toward the hazard, you held your finish, eyes locked on the ball. Bruce said he asked you, “Why are you posing like that, staring at the ball?” And you said, “Because that’s my punishment.” Is that true? And was that a moment you felt you could learn from?

True. I wanted to suffer the consequences fully of the bad shot, then go find it and start over.

You were a psychology major at Stanford, so maybe you could help with this dream I have where I keep trying to tee up a ball and it won’t stay on the tee. Stressful. I’ve talked to a lot of golf friends, and they have similar dreams. I was wondering…

Mine’s the one where I take back the club and the gallery is standing right here [gestures behind], and I can’t get the club back. The other one is hitting a putt uphill and it comes back at me. Or when the putt goes up and it’s like Mount Vesuvius, and the ball goes down the other side and rolls 30 to 40 feet away. That’s the nightmare.

I’m relieved to hear that elite players have those nightmares too. What do you think it’s about?

It’s the complexity of the human mind and the shared feelings we all have playing the game — of pressure, of challenging situations. The mind puts them in a box, and sometimes when we’re asleep and REM hits us, all of a sudden the box opens up.

And the darkness comes out.

Then you wake up.

You were so close to a sixth win in 2009 at Turnberry. How often do you think back on ’09?

Only when people like you ask me about it.

You never think about that approach on 18? You talked about bounces in links golf. That seemed like the ultimate bad bounce.

Well, I can still visualize the shot coming down: It was splitting the pin. And I flashed back to ’77. I was thinking, Be close. And the shot hits the green and people cheered, and then I hear them go [makes sighing noise].

Did you have the same feeling as the crowd when you saw the ball roll over the green?

I just said to myself, “Alright, let’s get the job done. Let’s get it up and down.” Which I didn’t do. But one of the great things came afterward. I was with Hilary, and her phone rang. It was Barbara Nicklaus calling her to say that Jack wanted to talk with me. So Hilary puts Jack on the phone and he says, “Tom, today I did something I’ve never done before. I watched a tournament from the first shot of the day to the last shot of a playoff.” And then he describes the last hole. He says, “You hit a perfect drive. You hit a perfect approach. If it stops six inches short, you win the tournament. Third shot, you hit the shot that wouldn’t lose you the tournament. And the fourth shot? You hit it like the rest of us would have hit it, you dog!” I still think about that today. The greatest player who ever played the game calling me up and making me laugh to try to console me, because he knew the pit I had in my stomach.

I was looking at a photo earlier of Stewart Cink hugging his caddie right after he beat you in that playoff. And what struck me about it is that you’re standing right there, smiling at them. You look genuinely happy for him.

I was sharing in his joy. I almost had it. The other thing to remember is that I had won it five times, and that guy hugging his caddie, that was his first.

Now you’ll be back as an ambassador at this year’s Open. What does that entail?

Basically, I’m an entertainer. Sponsors have me come over, and, if you buy into this program, you get a chance to play with an Open champion.

Will your hand and shoulder be ready to play?

No. But I’ll drive around. I’ll meet all the groups. Tell stories. Try to help them out with their swings. Maybe talk a little smack. That’s basically what I do now: I entertain people with my golf. And, frankly, I quite like it.

So, you’re okay playing what Curtis Strange calls “jolly golf”? I know that a lot of guys who played at the highest level have a hard time doing that.

I still enjoy playing golf with friends and helping people out. When I was growing up, I played golf with my dad and his friends and learned how they interacted with each other. And even when I got better, I still played golf with amateurs, 12 to 15 handicaps. We’d still go out and compete. I still enjoy that.

Do you miss it now?

Of course I do. I’ve got a rich life, but, in the end, I’m a golfer. That’s what I am.

You’ve mentioned that that’s how you’d like to be remembered: as a great golfer. Did you meet your own high expectations on that front? What kind of grade would you give your career?

Let others assess. Not me.