The Chef groans.

He rubs his eyes, sinking into a seat in the dining room of his home golf course, TPC Potomac. He takes a few deep breaths.

His mind goes elsewhere for a moment. It returns as he reaches for his phone.

“This is José Andrés,” he says soberly. “I need to speak to the White House.”

His playing partner and good buddy David Chow’s jaw drops from the other side of the table, his head cocked slightly in disbelief.

“Did you just say … the White House?”

***

SOMETIME IN THE WINTER OF 2016, José Andrés’ phone rang.

It was Sergio Garcia.

As almost every story involving José starts, somebody needed help. Garcia had been an excellent professional golfer, achieving fabulous wealth and international fame, but on the eve of his 34th birthday, Garcia still had holes in his resume. With 20 pro victories but no major wins in 73 attempts, his legacy hung dangerously in the balance between historically good and quickly forgotten.

“He called me out of the blue,” José remembers, his eyes widening. “He had this … energy.”

The request was formally a job offer: Garcia needed an in-house chef for Masters week, and he could think of no one better suited to run his kitchen than the best chef he knew, José.

Trouble was, José was already booked solid. He was busy trying to feed the world. And feeding the world doesn’t necessarily allow for a week of flipping omelets at a rental home in northeast Georgia, as Andrés tried to explain.

“I need you, José,” Garcia said.

“Everybody needs me,” Andrés said.

Garcia was relentless, and soon it became clear that he really did need José.

You see, Sergio and José were kindred spirits — two Spaniards who immigrated to America alone as kids with immense talent and limited language skills. Andrés arrived in New York City with $50 in his pocket and three years of training under one of the godfathers of modern Spanish cuisine, Ferran Adrià, and soon ascended the ranks of the city’s culinary scene. He moved to D.C. and took his first big swing with minibar, a 25-course menu of Spanish small plates served to just a handful of diners each night. The restaurant is largely credited with bringing the tapas revolution to America, and was awarded two Michelin stars in 2016, turning José into a food celebrity.

Sergio found a fortune in America, but José found a level of achievement that eluded his counterpart — one that Garcia hoped to find in Augusta.

So the Chef named his price.

“I’ll cook for you in Augusta,” he told Garcia. “But only if you promise you’ll win the Masters.”

“Fine,” Garcia said, cracking a smile. “If you cook for me, I’ll win the Masters.”

Six months later, José was next to Sergio’s father, Victor, when Garcia’s winning putt disappeared on the 18th green at Augusta National.

“I don’t know why these things happen to me,” José says now, chuckling. “But they do.”

The hours that followed are hazy. He remembers serving as Victor’s impromptu interpreter for an interview with CBS. He remembers champagne, many bottles of wine and the celebratory drink he declined in the legendary (and off-limits) Butler Cabin basement in favor of a prized cigar. (“I didn’t know the cabin was famous!” he says innocently.)

Mostly José remembers the look in Sergio’s eyes. His friend had fulfilled his wildest dream, and yet he seemed to be drawing from a different source of nourishment.

“It was fun to have José around,” Garcia told me the other day. “Not for the cooking, but for the energy and charisma and laughter he brings to everything he does.”

“He didn’t need a chef that week,” José says. “He needed my spirit — our spirit.”

And that made José happy. Job well done. Done, that is, until Sergio found him again at the end of the night.

“I need you next April, José,” he’d said. “For the Champions Dinner.”

JOSÉ IS EVERYWHERE, which is perhaps why his phone never stops ringing.

On line one is the José you think you know — the celebrity chef. From up close, the machine is dizzying. José is the owner and face of the well-greased restaurant empire José Andrés Group, which seems to grow in size every 15 minutes and offers an ever-expanding suite of media offerings featuring his eponymous face. The timing of our round of golf intersects with PR blitzes for a new Amazon Prime television show and another cookbook called Zaytinya. A question about his restaurant in D.C. yields a question in return.

“Which one?”

On line two is the José you want to know — the golf diehard. This is the José I’m excited to meet. The guy who hangs with pro golfers like Sergio Garcia and Collin Morikawa, who caddies in the Masters Par-3 Contest, and who knows the secrets behind the Champions Dinner, which he has helped this year’s host, Jon Rahm, prepare.

But it’s the José on line three that you really should meet. José, the savior. The guy who’s trying to feed the hungry and save the world. He’s not the guy I’m expecting on the morning we play golf, but it’s not his benevolence nor his confidence that surprises me.

It’s just that before I met José, I was pretty sure nobody could actually save the world.

Now I’m not.

SHORTLY AFTER 9 A.M. on a crisp and bright March morning, José’s phone rings again.

It’s work.

José — or “Chef,” as almost everybody calls him — is already one cappuccino and five calls into the day. He is on the practice range at TPC Potomac, banging balls into the ether while he holds court over speakerphone. This behavior may violate club rules, but José is too beloved by everyone here for those restrictions to apply.

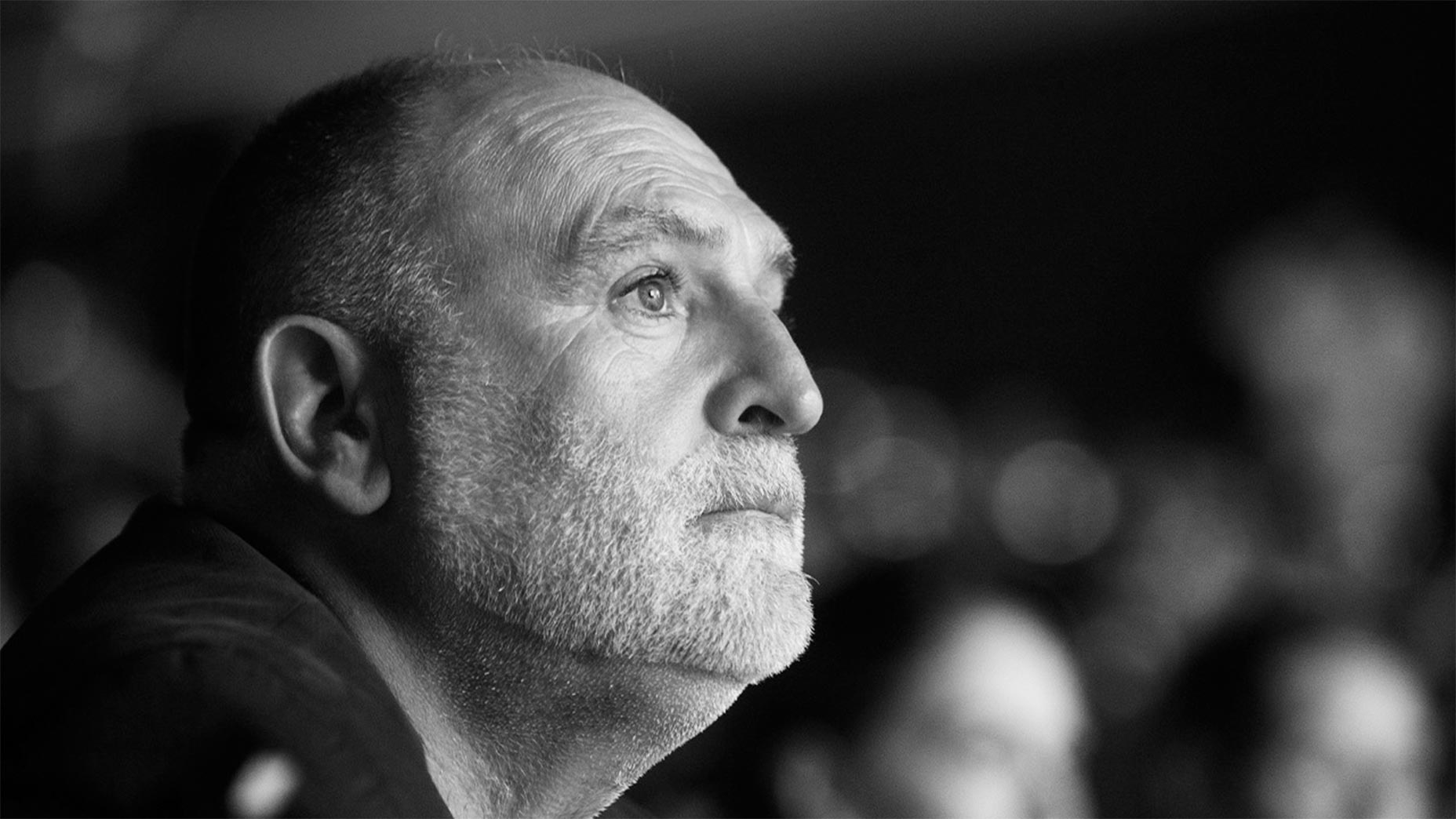

His broad build fits his disposition: larger than life, with a glistening white beard that has the peculiar effect of exaggerating his already-theatrical emotions. Last year, when José wore Augusta National’s iconic all-white jumpsuit to caddie in the Masters Par-3 Contest, fans began approaching him with Sharpies and the tournament-issued gnomes. They thought the club had hired the chef to dress like a garden ornament.

José has a personality of contrasts. He can be both gruff and vulnerable; harsh and tender; rabidly competitive and rib-piercingly funny. As a chef, his existence depends upon punctuality, but he doesn’t excel at brevity. By the time we’re headed back toward the 1st tee, he’s 20 minutes over time on a call with his team and using phrases like “and just two more things…” This may be typical of a José Andrés phone call, but his endurance is impressive to watch considering the pace of his delivery, which appears to leave him out of breath. (José can stuff more information into 20 minutes than most can fit into an hour, the vigor and tenacity of his voice smashing through bullshit like a sledgehammer.)

But that’s not what’s interesting about this phone call. I’m eavesdropping because I can’t believe what he’s saying — nor the casualness with which he is saying it. The topic of discussion? Only the day’s efforts to feed the people of war-torn Gaza.

José wasn’t sure what to expect when he founded the non-profit World Central Kitchen in 2010, but the last 15 years have proven it to be nothing less than his life’s purpose. His goal is refreshingly (and almost biblically) benevolent: To feed the hungry. And it doesn’t take long to realize this is by far the most revealing and foolish of his pursuits, as his buddy David Chow jokes plainly.

“Just think about how good you’d be at the important things in life, like golf,” David tells José. “…if you weren’t so busy trying to save the world.”

On the day we meet, World Central Kitchen has been tasked with organizing a supply drop to Gaza, where a stiff blockade and months of war have left millions of citizens starving. It goes without saying that this task requires Herculean coordination and temerity from dozens of people, but it is perhaps worth mentioning that the job also receives the complete attention of the celebrity face of the organization.

As the work call reaches its 35th minute, it is obvious to even the most cynical observer that positive PR does not drive José’s involvement with WCK. His voice sounds animated and even a bit anxious as he speaks, repeating the details of the morning’s mission a few times because they seem to settle him.

Landing a supply drop in Gaza is challenging beyond the obvious difficulties of flying military planes into a warzone, because, as José explains, attempting to feed this particular group of the hungry involves making a few facts clear to the key figures of Gaza’s explosive diplomatic powder keg. First, there is no ulterior political motive at play from José or World Central Kitchen; second, World Central Kitchen is alone in organizing the drop; and third, World Central Kitchen’s sole interest in organizing the drop is to feed hungry and innocent people. (World Central Kitchen often asks for help from nations, including the U.S. and EU, to execute its missions — José describes it as “hey, let me use your airport” diplomacy — but the unpopularity of some Western governments in Gaza has his organization treading carefully.)

This isn’t supposed to be thorny stuff. If anyone is qualified to handle issues of food, timing and location on a massive scale, it is José Andrés. And if there’s any message that everyone can rally behind, it’s that we ought to feed the hungry.

But nothing today will be simple for José. Except for the golf.

THE CALL ENDS on the 1st tee box, and for the first time all morning, José’s true self appears.

He holds what turns out to be a meticulously maintained 19 handicap, which technically makes him a below-average golfer. But the thing he loves about golf is that it’s the most “democratic” sport — allowing any two players to compete, no matter their ability.

Like a true competitor, he spends his free moments pre-round pushing the limits of golf’s democracy by bemoaning his lack of recent play and begging me, his competition, for more strokes. After he’s bludgeoned me for an extra five or six shots, he spends the afternoon joyfully tearing me to shreds with net pars and birdies.

“You’re young and you can hit it far, but you’re not ready,” he teases. “I can’t wait to tell my friends I beat a golf writer.”

He’s talking plenty — the rare type who yells at both good and bad shots — but he’s also striping it. On the 10th hole, he fades a gorgeous approach around the trees and unleashes a full-fledged scream.

“C’MON, BABY!!!” he bellows, his voice echoing so loudly through the valley it literally stirs birds from the trees.

These are the sounds of a man in love with golf, which is not someone José Andrés ever thought he’d be.

Andrés found the sport on a family vacation about 15 years ago, bought a set of clubs the next week and has been obsessed ever since. He says he’s always been an athlete, playing sports all over Barcelona as a child, and golf has provided him a grown-up competitive outlet. (Andrés’ subsequent stretch of stories detailing a brief and perhaps controversial run of utter dominance as a teenage street basketball player in Spain, are, for obvious journalistic reasons, here omitted.)

His house backs up the claim. His living room is loaded with sports memorabilia, including trophies from splashy golf events like the Ryder Cup celebrity pro-am and a big-money tournament at the famed Spanish club Valderrama. Three years ago, José walked in a birdie to win TPC Potomac’s member-member in a playoff. The trophy remains in the clubhouse, etched with his name, and is his proudest golf achievement.

“I’m a pretty intensely competitive person,” says Chow, who won the club event with José. “I’m not sure José knows that because I’ve never had to show it. He has enough competitiveness for three people.”

A round can tell you a lot about a man. In José’s case, our round first reveals that he is a golf addict. As the 11th hole comes into view, he laughs maniacally, recounting in great detail how the par-4 played as the hardest hole on the PGA Tour in 2022 and famously helped foreshadow Sergio Garcia’s departure to LIV. Second, our round reveals that José is savvy to golf’s business superpowers — he plays with custom-branded ProV1s that read: “Bring to Jaleo and get one gin & tonic on José Andrés.” (“We try not to give out too many of those,” he says with a wink.) And third, our round reveals that José uses his golf addiction and savviness to help advance his nobler pursuits, like feeding the hungry.

One example came back in 2017, when José cooked for Garcia at the Masters. At the beginning of the week, José mentioned that he was hosting a fundraiser for the Food Bank of Augusta on Friday night. When Friday night rolled around, Garcia — then tied for the lead and attempting to change his life’s trajectory — showed up at the event and spent three hours raising money.

“He just never stops,” Sergio says when I ask him why. “It rubs off on you.”

But even the guy trying to feed the world has limits to his benevolence, like when his golf writer-turned-playing partner is standing over a two-footer to win a hole.

“Let’s see him make that,” Chef says with a devilish grin.

Which is the fourth thing you learn when playing golf with José Andrés: No gimmes.

AROUND THE 12TH HOLE, his phone rings again.

It’s Jon Rahm.

The two have been chatting a lot recently, mostly by text, for an upcoming engagement: the Masters Champions Dinner. Rahm, you might recall, won his first Masters last April, which means it’s his turn to host golf’s holy dinner — a multi-hour, several-course affair that is arranged (and paid for) by the tournament’s reigning champion. Three dozen or so former winners will attend, and the work of preparing the menu takes several months.

Rahm’s menu, though, has been in motion for much longer than that. The Spaniard claims to have retained José’s culinary insights for the Champions Dinner years before Rahm even won.

Andrés’ phone exploded last April, minutes after Rahm’s victory, when the golfer proudly told the world Chef José would be building his Champions Dinner menu.

“I’m like, I told you this a million times, José, you’re cooking for me at the Masters,” Rahm says.

José remembers no such agreement.

“I thought, ‘Well, s—t, I guess I’m helping out at Augusta,’” he says with a chuckle, his inflection leaving him to pronounce the club “ow-goos-ta.”

Augusta National is familiar with José, given he helped Garcia craft his own Champions Dinner menu in 2018, and the reverse is also true. Andrés has high praise for the club’s culinary team — a group he calls “top-notch.”

“And I don’t mean ‘top-notch for a golf club,’” he says. “They’re serious cooks.”

Worried about running afoul of Augusta, José keeps the details of crafting the menu close to the apron. He says he will be sending a team of his top lieutenants to assist with operations and insists that no dinner attendees will leave hungry.

Rahm and Andrés have settled on a spread that rivals any in Champions Dinner history, honoring Rahm’s Basque heritage with a tender intentionality that’d make Juan Elcano blush. Among the personal touches on Rahm’s menu: his favorite dish, Chuletón, a shared-plate steak served no warmer than medium-rare; a Basque lentil stew whose recipe comes from Rahm’s grandmother; a limited-edition run of a 30-year-old bottle of wine, Imperial, hand-sourced by Rahm’s grandfather; and, for the first time in Masters history, an array of small plates loaded with Rahm’s favorite tapas y pintxos.

The communal spirit of the Champions Dinner menu is for Rahm, but it works on a few levels. It doesn’t take a culinary expert to know that golf badly needs this meal, and what better way to remind a broken sport of its priorities than by sharing a plate?

José refuses culinary credit — or any responsibility, really — for Rahm’s menu, saying only that he has helped “bring Jon’s vision to life.”

The text messages on the morning we play golf indicate he’s done more than that. A photo of a dry run of the dessert dish made by José’s team — named Milhojas, a gorgeous puff pasty stuffed with delicate lattices of custard — gets a two-word response from the Masters champ.

“Que bonitoooo!” (“How pretty!”)

Rahm is less guarded about Andrés’ involvement.

“That was José’s doing,” he says of a pintxo named Chistorra. “I don’t even know how to explain it to be honest. It’s wrapped in potato. I’m going to trust him on that one.”

As a golf nerd with a nose for the game’s history and traditions, Rahm took seriously the business of constructing the menu. Fortunately, food is serious business for José, who would sooner shoot 120 than disappoint his guests. Rahm knows firsthand.

“My wife Kelley loves it,” Rahm says. “I’ll say, ‘Hey, man, I’m around,’ and not an hour later he shows up with massive plates of food.”

Rahm would like to think he’s unique in that experience, but he knows all too well he isn’t. You don’t feed the world by keeping a small circle.

“He’ll come back from being in Haiti, or Ukraine,” Garcia says. “It’ll be 1 in the morning, and he’ll say, ‘Okay, what do you guys want?’ He’s tired, but his first thought is, ‘Let me cook something for you.’”

“He’s showed up at my house on accident, too,” Rahm says, laughing. “At one point he showed up to watch the Real Madrid match and I said, ‘You got the wrong guy, you’re looking for Sergio.”

Rahm also remembers what he told José at the door.

“We’ll still take the food.”

AFTER OUR ROUND, José’s spirits are high.

He’s won again, a 1 Up victory courtesy of a six-footer for a closing net par. His trash-talk carries him back to the TPC Potomac clubhouse for lunch. But before someone can take our order, his afternoon takes a turn.

A notification pops up on his phone, and it’s quickly obvious that something is wrong. He falls silent, quietly dropping his head into his hands.

After a few seconds, he picks up his phone.

“This is José Andrés,” he says. “I need to speak to the White House.”

“Did you just say … the White House?” Chow asks.

José doesn’t respond. A few minutes later, he places another phone call. He sounds anguished.

“It’s José … there’s been an accident in Gaza … one of the parachutes didn’t deploy.”

A long pause.

“There’s been a loss of life.”

On this day, in addition to World Central Kitchen, six countries have sent humanitarian aid planes to Gaza. Usually, supplies are lowered to the ground by parachute, landing with a gentle thud. But one of the parachutes on one of the planes malfunctioned, sending a few hundred pounds of cargo cratering unabated toward the earth. Nobody knows whose plane was responsible for the mishap, but the reality is grim: Five people are dead.

A horrible quiet lingers over the table. There’s so much to say — the tragedy was nobody’s fault; so many more lives were saved by the airdrops; nobody could have done anything to prevent what happened — but it’s no use. The news cuts José deeply. He isn’t responsible, but he feels that way.

A few minutes after the call, his phone rings and he leaves the table. He returns and doesn’t elaborate.

Suddenly, a tiredness washes over him. The energy from his victory has evaporated. He sighs.

“Did you know that I’ve flown around the world one-and-a-half-times this year?” he asks, recounting a World Central Kitchen flight manifest that begins with an eastbound flight from D.C. to Tel Aviv and ends with an eastbound flight from Ukraine to D.C with a stopover in Hawaii, noting he’s added a few D.C.-to-Europe legs for kicks.

“It’s March,” he says quietly.

José is everywhere. He founded World Central Kitchen because he was galled by widespread hunger in the aftermath of natural disasters in New Orleans and Haiti. But the crises keep coming, and people keep starving, which means José — and his non-profit of more than 100 — keeps working.

But nothing about the world seems to make sense anymore, not even to the people who have committed their lives to the frontlines. Just this week, José received another devastating phone call. An Israeli airstrike struck a convoy of aid workers on a humanitarian mission in the Gaza Strip.

Seven World Central Kitchen employees were killed in the strike — Zomi Franckom, a 43-year-old Australian; Saifeddin Issam Ayad Abutaha, a 25-year-old Palestinian; Damian Soból, a 25-year-old from Poland; Jacob Flinkinger, a 33-year-old dual U.S.-Canadian citizen; John Chapman, a 57-year-old from the UK; James Henderson, a 33-year-old from the UK; and James Kirby, a 47-year-old from the UK. In the moments following the news, World Central Kitchen said it had paused all operations in Gaza.

“These are people … angels … I served alongside. They are not faceless,” José said in a statement. “The only crime they committed was feeding people.”

It’s difficult to express the depth of the heartache. Every time the world hits rock bottom, a new tragedy starts calling.

“I look around at all these hungry people, and it seems like everybody’s forgotten about them,” José says. “We started in Haiti, then Houston happened. Irma, then Maria…”

He starts ticking through a list of international tragedies he has personally witnessed.

“All of a sudden it’s 15 years later,” he says.

It’s hard for José, or anyone at WCK, to rationalize feeling fatigued. How can you take a moment to breathe when so many people need you? What do you tell the people in the trenches with you? And what do you tell the families of those who gave everything for the good fight?

But it is exhausting. On afternoons like this one, the work must feel Sisyphean: always another mouth to feed, but never time to feed yourself.

Which is what makes José’s determination so honorable … and maybe so trying. He forges on even knowing the toll. Even knowing the hard world that awaits him. Even feeling the same sad and cynical urges that weigh on the rest of us — and, unlike the rest of us, knowing exactly how much sadness and cynicism is actually out there.

I break the silence with a simple question. Why keep going?

“At some point, you realize if it’s not going to be you, it’s not going to get done,” he says. “You do it because you can. And if you can do it, you can carry things forward.”

In this hopeless moment, it suddenly hits me that José Andrés is still hopeful.

And if he can feel hope, why can’t we?

BACK AT HOME THAT MARCH AFTERNOON, José has perked up.

His wife Patricia (he calls her Tichi) is enjoying a late lunch, which has afforded José the opportunity to make her dough for empanadas. Her presence brings some warmth back to his voice, and the small act of service appears to energize him. He apologizes for his phone usage earlier in the day.

“I don’t normally do that when I’m playing golf,” he says. “Today was just so crazy.”

The sentiment is sweet, even if neither of us believes it.

We sit over a cappuccino in his backyard, which will soon bloom into a brilliant garden. During the summer and fall, he grows as many fruits and vegetables as the space allows. He forages during his golf rounds for the items his garden can’t provide, and his wayward drives yield a small fortune. His home club is fertile ground for fungi, particularly chanterelles.

Sometimes José daydreams about the simple life of a chef, cooking unfussed meals for loved ones using ingredients sourced straight from the earth. But life isn’t that simple anymore.

In an ironic twist, José’s work for others has exponentially increased his celebrity. He holds meetings with heads of state, and his work regularly receives international acclaim. José missed defending his title in the member-member after President Biden summoned him for a trip on Marine One.

He enjoys the perks of fame — the annual Masters invite from IBM isn’t too shabby — but he mostly resents his profile.

“It created a little aura around me, which is nice … for the first 10 selfies,” he says, shaking his head. “That’s not why I do it.”

The reason why he does it is sitting in the other room. Tichi was the brains behind World Central Kitchen, he says, and is a fierce advocate for having a platform and utilizing it. José just liked the idea of jumping out of airplanes and saving the world.

He was 40 when they founded the organization. At 54, he’d be alright with fewer airplanes. But there are still mouths to feed, so the work continues.

“I believe it’s not about who you are, it’s about your intentions,” he says. “People forget that.”

José does not. He intends to keep feeding the hungry. Not all the hungry. Hell, he’s not even feeding most of them. And even then, it’s hard work to keep it from falling apart.

José may never satisfy his own appetite. When he’s gone, the world will still be hungry. Sometimes he feels like a fool for dedicating his life to the pursuit. But he learned a long time ago that the only secret to doing anything worth a damn is being foolish enough to try.

“Everything is so complex,” he says. “Everybody seems to believe that my truth is the only truth. There are many truths. And the only actual truth is that there are very good people on every side. People who want a better, more peaceful world. We can’t leave them behind.”

And we won’t, because José is going to keep trying, no matter how mighty the challenge or how unreasonable the goal. This, it turns out, is how things get better — not by hoping, thinking, whining or moping — but by doing. Better will arrive slowly, and often painfully, but it always comes eventually.

Sound familiar?

“I dream of a hole-in-one, but I don’t know if I’m ever going to get it,” José says, pausing ever so slightly. “If I can just keep my ball moving forward, I’m happy.”

Saving the world is hard, I say. Golf sounds a little easier.

He grins. The kitchen is calling.

To contribute to World Central Kitchen in honor of the lives lost in Gaza, follow the link here.

You can reach the author at james.colgan@golf.com.