It’s been 35 years since the Golden Bear, in the twilight of his career, summoned that old Jack magic to bring home the greatest triumph in Masters history. His son Jackie was on the bag that day, but it wasn’t the first time he’d looped for his dad. In this excerpt from his soon-to-be-published book Best Seat in the House, Jack Nicklaus II remembers putting the Bear’s bag on his back — and being guided by his father through a lifetime of invaluable lessons.

While I certainly never planned on it, caddying for my dad, Jack Nicklaus, presented an amazing way to learn more from him as he offered lessons about the game of golf and, more important, about life.

The first time I ever caddied for Dad was at the Open Championship at Royal Birkdale Golf Club in Southport, England, in 1976. It wasn’t by plan or design. Dad’s regular Open Championship caddie was Englishman Jimmy Dickinson. Jimmy first caddied for my dad at the Open Championship in 1963. He was on Dad’s bag for two of his three Open Championship titles (1970 and 1978), and they had a great partnership.

I walked the course with Dad as he played his practice round with Raymond Floyd before Thursday’s opening round. On the approach to the 9th hole, Jimmy tore his Achilles tendon and couldn’t continue. Jimmy asked me to carry Dad’s bag to the 10th tee while he looked for a replacement caddie.

While we waited, Dad looked at me and said, “Why don’t you carry the bag for me on the back nine?” At 14 years old, I really didn’t have time to react or even process what Dad was asking. I certainly did not register how much trust Dad was placing in me. I just grabbed the bag, which probably weighed around 50 pounds, and went to work (so to speak). Dad’s drive off the tee landed in the middle of the fairway, followed by a perfectly struck 4-iron that landed on the green about five feet from the pin. I watched the flight of the ball, and it seemed to defy gravity with its height and hang time.

I hoisted Dad’s bag over my right shoulder, and we walked side by side down the fairway. Although I had spent so much time with Dad on the golf course, it had not been as a caddie. I was like a deer in the headlights, and I was so overwhelmed. I was only a few minutes into my new gig when Dad quickly reminded me of my new responsibilities. We had walked about 30 feet when Dad stopped and asked me, “Didn’t you forget something?”

I was surprised by the question and had no idea what Dad was talking about. I turned and looked back down the fairway, thinking I might have dropped a club or that maybe Raymond Floyd had not hit his approach shot yet. I was confused and looked it. Dad pointed to a small chunk of turf that was bottom-side-up in the middle of the fairway behind us.

“You forgot to replace the divot,” he said, regarding the green turf displaced by his approach shot.

Having let my new role get the better of me, I was embarrassed as I found the dislodged turf and replaced it. This was “Golf 101,” an etiquette rule I knew as a golfer. It was time for me to focus since I was in Dad’s office — and this was serious business.

I set Dad’s bag down on the fairway, and nobody replaced a divot quicker or better than I did then. It was the best replaced divot in the history of replacing divots!

Now, the nerves surfaced. I was a wreck, worried because Dad said he didn’t need a replacement caddie for Jimmy. He had me, and I was wondering whether or not I was up to the task. Yet, as he always is, Dad was incredible. Honestly, it was hard to believe he played so well—Dad finished in a second-place tie with Seve Ballesteros, six strokes behind winner Johnny Miller. Dad was at a huge disadvantage with an inexperienced son-turned-caddie on his bag. I didn’t know anything about being a caddie other than the oft-repeated mantra, “Show up. Keep up. And shut up!”

When I caddied that first time for Dad, our relationship changed. He was Dad first and always, but I also quickly understood that he was working when on the course. Golf was his profession, what he did for a living to support his family. Out there I saw him as a competitor for the first time. With me on his bag, I also understood I could help or hurt his performance.

Mom and Dad had to have been entertained by my first efforts, since I was determined to be the best caddie I could be. And, boy, I overdid it at times.

Like most guys on the PGA Tour, Dad always marked his golf balls with a pencil mark on either side of the number on the ball. It was something he always did just before he teed his ball up on the first tee of a round. It was a light press of the pencil lead, barely visible, but enough to distinguish it if there was ever a question of golf ball identification.

Dad never marked his golf balls during a practice round. So, after his practice round at the Open Championship in ’76, I wanted Dad to be prepared. I marked all the golf balls Dad planned to use in the next day’s opening round before we went to bed. At that time, balata golf balls were the choice for professionals and low-handicap golfers. The soft balata cover allowed for more control off the tee and much higher spin rates on iron and wedge shots.

I was determined to mark Dad’s golf balls like no others. I planned to have the most thorough markings ever on a golf ball. Well, I went through pencil after pencil after pencil as I marked those golf balls. I can’t tell you how many tips of pencil lead I broke off into those soft balata covers. All I can say is there was no mistaking those markings on Dad’s golf balls — they stood out like pimples on a teenager’s nose. I am not sure how counterproductive my excessiveness was, but Dad’s brand-new golf balls had slight pieces of lead sticking out of them.

Dad never demeaned my efforts as he gracefully searched for balls in his bag that were not terminally damaged by me to use in the competition. He gracefully asked me to give the forever-scarred golf balls to his adoring fans in the gallery. Everyone was happy — and, at the time, I didn’t know any differently.

I still remember the 17th at Royal Birkdale, when I first caddied for Dad. At that time, Dad played with the Slazenger B51 golf ball. Dad’s drive off the tee found the right rough, where the thick grass was nearly 18 inches long. A slight wind of five to ten miles per hour was at Dad’s back, and the yardage to the pin was 247 yards. Dad looked at his golf ball, settled in the lower section of the grass, and grabbed his 7-iron. I was sure he planned to lay up and asked him about his line — I thought he wanted to land the ball in front of the cross bunkers near the green.

Surprised, Dad looked at me and said, “I am putting this on the green.”

Dad’s powerful swing tore what looked like four- or five-foot strips of grass blades from the ground. Anyone who has hit from high rough understands how quickly that grass will grab the club’s shaft, turn the clubhead and result in a quick shot to the left. Not only did Dad keep that 7-iron square, he made great contact with the golf ball. It sailed high and true toward the target. In fact, Dad hit it too strongly. The ball landed on the green, near middle, and bounded over. The ball traveled 265 yards!

Dad’s steadfast support of caddies is well known. He was, in fact, a caddie himself as a kid, carrying the bag for his own dad — my grandfather Charlie — at Scioto Country Club in Ohio.

Dad didn’t rely on one specific caddie during his professional career, though Angelo Argea, Willie Peterson and Jimmy Dickinson were on his bag many times and were part of his championships. Angelo, who was known as the “Silver Greek” for his gray afro, was on Dad’s bag for 44 of his 70 PGA Tour wins. In fact, Dad won five of the first six tournaments he played with Angelo on his bag. Willie first caddied at the Masters at the age of 16 and was on Dad’s bag for five of his six Masters titles. I was on the bag for Dad’s sixth and final Masters win in 1986. More on that in a little bit.

For all the ways in which he counted on caddies, Dad has never been “clubbed” by one — that is, a caddie never told Dad which club to use or handed him a club for hitting a shot. Dad selected the club himself. For instance, if Dad’s approach shot from the fairway was 158 yards to the pin, he might have played six or seven different clubs. He might have choked down on a 4-iron or hit a 9-iron to spin the ball.

The longer I caddied for Dad, the more I realized my main responsibility was to be his friend on the course. Yes, I did the tasks required as his caddie. I cleaned his clubs, held the umbrella when it rained, marked his golf balls, tended the pin, helped him sidestep any distractions. But my job was to be his friend and, if necessary, help him refocus.

Here’s an example: I was on Dad’s bag at Augusta, and he had a 155-yard shot over a front bunker to the pin. When Dad rolled the sod over his 7-iron and the ball landed in the bunker, he said, “I think there’s something wrong with that ball.” I asked him what he meant, and Dad said he felt the ball’s flight wasn’t correct. But I knew he hit the ball fat because I heard the sound.

I said, “Dad, you hit the shot fat.”

Dad’s immediate answer was, “No, I didn’t.”

I quickly learned my response wasn’t what Dad needed to hear. Dad controlled what he could control on the course, and, in his mind, the ball didn’t fly like it should. I learned after a short time as Dad’s caddie to be more supportive and act as his friend. It was a quick learning experience as I took that golf ball out of play before the next hole.

After Dad won the ’86 Masters, Greg Norman, who finished tied for second with Tom Kite, thought having me on the bag was the secret sauce to his win. I regret to say I was not the secret sauce. It just so happened Dad was a great player, and he dragged me along on that victory.

“What is it like to be Jack Nicklaus’ son?”

It’s a question I’ve been asked many times throughout my life. I had never pulled back the curtain and given an in-depth answer until I spoke at the Congressional Gold Medal presentation for my dad in 2015, in Washington, D.C. During my speech, I discussed in detail the 1986 Masters, where I served as Dad’s caddie. Not many had given Dad a chance at victory because they thought he was past his prime at the age of 46, but he proved everyone wrong. He shot a final round of 65, seven shots under par, with a 30 on the back nine, for a total score of 279 to win his record sixth Masters. He became the tournament’s oldest winner and the second-oldest winner of any major championship, behind Julius Boros, who at 48 won the 1968 PGA Championship.

Honestly, I didn’t think I was up to the task when Dad asked me to speak in D.C. In fact, I asked Dad if he wanted one of his peers, maybe his good friend Tom Watson, to introduce him. When Arnold Palmer was presented his Congressional Gold Medal in 2012, Dad introduced him. I knew how overwhelming it would be for me to introduce Dad, and I didn’t know if I could do a good job. Trying to be funny, Dad smiled and told me to consider it practice for his eulogy.

Dad had made me a part of it. I knew I had Dad’s full focus. I felt like I mattered. And I felt loved. That is what it’s like to be his son.

That didn’t make it any easier for me, but here is what I said:

To share some of my clarity with you, let’s go back in a time in sports history that many of us remember, the ’86 Masters. We’ve heard about it earlier, but I will tell it from a little bit different perspective.

It was a beautiful spring day in Augusta, Georgia. It was Masters Sunday. I was a 24-year-old kid carrying the bag for Dad. We were on the 9th green, and Dad had just backed away for the second time from a slippery downhill birdie putt. There had been back-to-back roars from the 8th green, where Tom Kite and Seve Ballesteros had each made eagles to extend their lead. I stood with the gallery there on the 9th green. There was a tension in the air. We were caught up in the moment of nervous energies of golf history. It was a moment that seemed to swallow us, all of us, except Dad.

Unexpectedly, Dad turned to the surrounding gallery, flashed a boyish grin and said in his high-pitched voice with a certain level of levity, “Hey, let’s see if we can make some noise of our own up here.” He then steadied himself at the task at hand. As he walked that putt into the hole, the crowd erupted, the game was on.

It was that final nine holes that is forever etched in my memory. I remember that fluid yet powerful swing. I remember the precision, the concentration, the intensity. I remember each heroic putt, each heroic shot. Above all, I remember the emotions. Dad clearly had a mission to give everything he had left. To manage the only thing he could truly manage, himself.

Yet I watched him struggle. I can still see the tears in his eyes and feel those in mine. It was the encouragement and the ovations the fans gave Dad those final nine holes that was unforgettable. Sure, the enthusiasm was fueled by the events of that day, but I knew it was more than that. The cheers represented an appreciation for a lifetime of accomplishments and the way he had done it. They embraced a good man with good character.

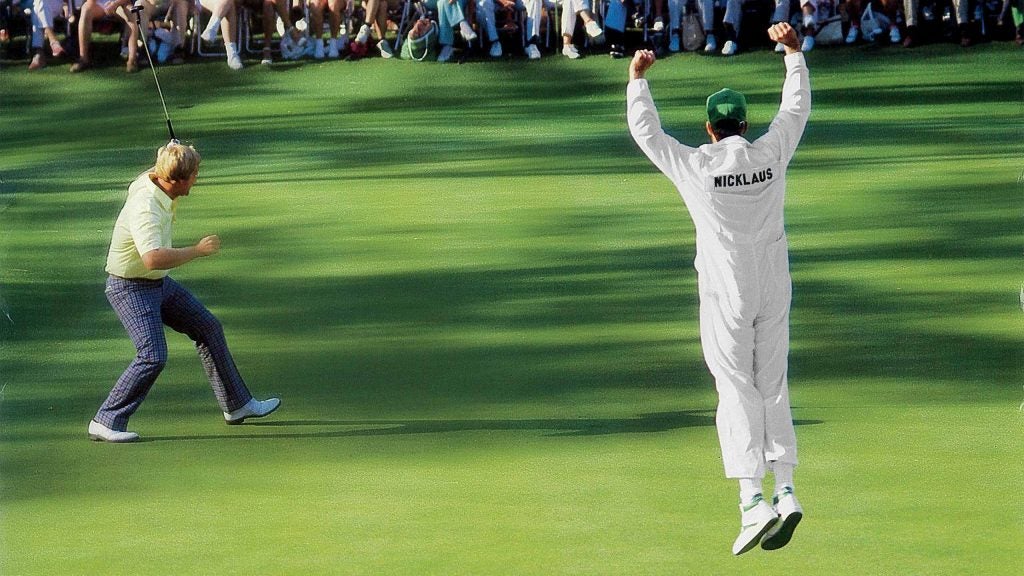

Dad was now on the 18th green. I stood motionless, holding the flag, as Dad putted out for a final-round 65 to complete his unlikely come-from-behind victory at the age of 46. As his final putt dropped, the crowd erupted. Dad quickly picked the ball from the cup and faced the crowd to greet their cheers.

And there I was, completing the mundane task of placing the flag back into the cup. For me, time was standing still as the cheers continued. I was thinking, Wow, Dad really played great today. Yet it was more, so much more. This man, this wonderful man, had accomplished so much. He is Jack Nicklaus; he is arguably the greatest golfer in the history of golf. The Golden Bear had just won his sixth green jacket in incredible fashion. His fans adored him. It was his moment in time. A moment so earned and a moment so deserved.

Now, let’s go back to that question that I am so often asked: What is it like to be Jack Nicklaus’ son?

So there I was, turning from the flag, and all I saw was my dad. In the midst of this moment — that was all about Jack Nicklaus — there Dad stood, waiting for me with the most wonderful smile. His arms were outstretched to embrace me. Dad had made me a part of it. I knew I had Dad’s full focus. I felt like I mattered. And I felt loved. That is what it’s like to be his son.

The envelope came to my house, and in it was a handwritten note in black felt pen. It was dated March 29 — five days after the Congressional Gold Medal presentation. It said:

Dear Son,

What can I say except that I am so proud of you and what you said Tuesday in Washington. Your talk was so good that I didn’t care what I said. You made your father one happy and lucky man. To know he has a son as great as you. You are the best!!!

Love you, Dad

I have been very blessed to play a lot of golf with my dad and to caddie for him. I have watched him compete, I have watched him win, I have watched him get beat and I have watched him build his incredible legacy. I’ve learned more from caddying for Dad than I ever did playing the game of golf. As his caddie, I also learned more about golf course management, game management and, frankly, life management than I ever did from playing golf.

And I owe it all to my dad.

Adapted from Best Seat in the House: 18 Golden Lessons from a Father to His Son, by Jack Nicklaus II and Don Yaeger. Copyright 2021. Published with permission of Thomas Nelson Publishing.