KAWAGOE, Japan — It’s been impossible to talk about golf and the Olympics without mentioning the biggest names in the game who will not be playing in Tokyo. Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka, Louis Oosthuizen, Adam Scott, Sergio Garcia, Patrick Cantlay … Sounds a lot like 2016, doesn’t it? During the run up to the Rio Olympics it was easier to keep track of who wasn’t competing in the men’s event rather than who was.

While numerous golfers have expressed some regret for not playing in 2016, it was just another iteration of a complicated relationship between golf and the Olympics. One that encompasses its entire history with the international event.

The London ‘Boycott’

Golf’s debut at the Games came in the 2nd Olympiad. Paris, in 1900. It went off without a hitch, with American Charles Sands winning the 36-hole stroke play event. The women’s event was just nine holes but produced the first gold medal ever for an American female with Margaret Abbot taking the top spot.

The 1904 Olympics in St. Louis added a men’s team event, removed the women’s event, and saw a Canadian, George Lyon, take the gold. All was well for golf at the Games, until the 1908 event led to its century-long suspension.

Much of the information is lost to history, but the 1908 competition, in which no medals were handed out, can be whittled down to a massive miscommunication. The Games were originally scheduled for Rome, but were moved to London after a Mount Vesuvius eruption. The British Olympic Committee asserts that they sent a note to the R&A informing golf’s oldest governing body that they should be managing the affair. Apparently, the letter was never received.

The BOC, never hearing back from the R&A, moved forward in planning the competition for six rounds, two each at Royal St. George’s, Cinque Ports and Princes Golf Club. The 108-hole proposal dwarfed the previous two Olympiads, and the R&A didn’t agree with it. Various British players were irked by the confusion surrounding it all, and coincidentally filed their registration papers incorrectly. Was it a sneaky boycott, as it has been described many times? Perhaps! According to the PGA Tour, it came down to a misinterpretation, or disagreement, of what ‘amateur’ meant. The result was a field of just one man who filled out his papers correctly the defending champ, Lyon. He was offered the gold medal as the only man remaining, but declined. The next Olympic gold medal in golf would be issued 108 years later to Justin Rose.

Augusta National, Olympics host?

It appeared like golf might make a triumphant return to the Games in the mid-90s after nearly a century away. With the ’96 Games being staged in Atlanta, it was up to the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games to propose new sports, if desired, as is routinely afforded host countries. The head of the ACOG? Then-future chairman of Augusta National, Billy Payne.

In October of 1992, it became clear the ACOG would petition the IOC to bring golf back into the games, and Augusta National was pegged as the perfect host course. It had sports writers dreaming about two weeks at Magnolia Lane. LPGA commissioner Charles Mechem was dreaming about breaking barriers. The first women’s competition at Augusta National would award a gold medal along the way? Sign us all up.

According to reports at the time, the format was already decided: 72 holes, stroke play. A maximum of three men and women from each country would shape the field. The R&A was in. The USGA was in. ANGC Chairman Jack Stephens was in. Golf had a lot going for it. What it didn’t have was full local support.

Atlanta City Council was a key stakeholder in approving Augusta National as the host course prior to Payne’s appeal to the IOC for golf’s inclusion in the games. Without the Council’s support, Payne couldn’t move forward, and the council did not support Augusta National’s institutionalized uniform membership. The club had just one Black member, and zero female members. How did that match with the mission statement of the Olympics and its pillar of equality?

It didn’t. And ironically, the best male players in the world once again largely scoffed at the idea. “I’m not juiced about it,” Tom Kite told reporters at the time. “I don’t know of anyone who really is. We have a lot of international events that serve the same purpose.”

“That would take some convincing,” Payne Stewart told reporters in 1992, wary of playing for no prize purse. “Most everybody out here is used to playing for something.”

Eventually, without the support required to appeal to the IOC, Augusta National as a host course fell apart. Golf in the Games fell apart. Payne’s proposal never advanced, and no new sports were added in 1996.

Re-entry is complicated

Getting back into the games is a battle, if you haven’t learned. With London hosting the 2012 Games, however, golf had new life. In 2005, it was announced that baseball and softball would be eliminated from the list of events, clearing room for a sport born in the British Isles. At least that was the thought. Support was just never strong enough. Four other sports were up for re-entry, and golf didn’t even pass the preliminary vote. Squash and Karate both advanced to a final vote ahead of golf, and neither were approved. Four more years to think about it.

Thanks to some savvy marketing from the IGF, which used Jack Nickaus and Annika Sorenstam as public figureheads, golf was voted back in to the Games in October 2009. It would join the slate of sports alongside rugby sevens for the Rio Olympics, scheduled for 2016. Live from the Presidents Cup in San Francisco, Tiger Woods chimed in:

“There are millions of young golfers worldwide who would be proud to represent their country,” Woods said. “It would be an honor for anyone who plays this game to become an Olympian.”

Fast-forward seven years, and that didn’t ring true. For one, Woods was battling chronic back issues, unable to play, and golf was battling the Zika virus, which was prevalent in host country Brazil. Similar to the current Olympiad, the World Health Organization issued declarations on whether or not to host the 2016 Games at all.

Ultimately it was considered safe for the Games to go on, and for people to visit Brazil, but many male golfers thought otherwise. Dustin Johnson, Jordan Spieth, Hideki Matsuyama, Jason Day, Shane Lowry, Rory McIlroy, Graeme McDowell, Adam Scott … each of them bowed out. Others followed suit. In the end, the strength of field for the men’s event plummeted to the level of a fall series event, nowhere near the status organizers had hoped for when Woods so confidently spoke about it in 2009.

Another Olympics, another virus …

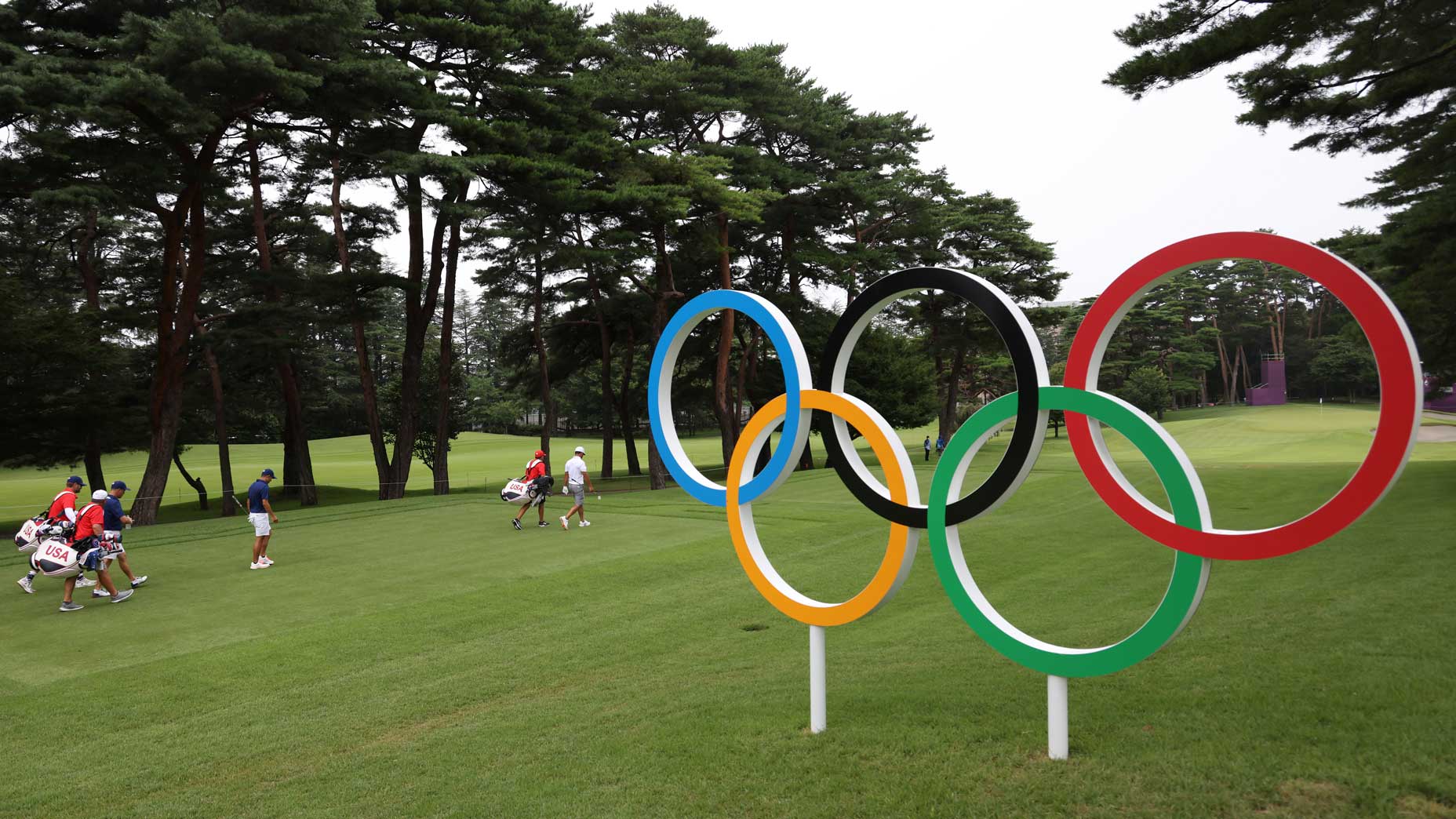

All of that brings us to 2021, and the 2020 Games, where something similar took place with the men’s competition.

After years of questions about commitment from the press, and 12 months of postponement to this week, the qualifying period for the men’s Olympic golf competition wrapped up on Father’s Day, the Sunday of the U.S. Open. The next day was a crucial one for the International Golf Federation as they needed to confirm the final field of Olympians. In the next 24 hours, once again, many of the game’s biggest names would pass on the Olympics.

Tyrrell Hatton, the No. 11 player in the world, declined quietly through the IGF to represent England. He was followed by fellow Brit Matthew Fitzpatrick. Englishman Lee Westwood had dismissed the Games months prior, so the honor dropped all the way down to Tommy Fleetwood, the third replacement.

Then there was Sergio Garcia, who tweeted out an explanation in Spanish that said he would skip as well. He did not send out another tweet with the message in English, like he normally does. And just days after embracing Jon Rahm, his fellow countryman, on the driving range at Torrey Pines, Spaniard Rafa Cabrera-Bello quietly declined to play, too.

South Africa’s Louis Oosthuizen bowed out of consideration for his second-straight Olympiad. Martin Kaymer, who played in Rio for Germany, chose not to play in Tokyo. Dustin Johnson, who bailed before the pandemic even became a reality in March 2020, stuck to this guns. The message from the men was resounding: we’d just rather not.

It was a nice sign for the IGF that Rahm had agreed to represent Spain. He was the No. 1 player in the world, and any event carries greater weight with him involved. McIlroy, who had shunned the Games in 2016, chose to represent Team Ireland. Justin Thomas, one of golf’s biggest stars, was all-in for Team USA. The field had some juice to it that desperately lacked in 2016. Then the Covid tests hit.

On the Saturday before the competition was set to begin, the No. 6 player in the world, Bryson DeChambeau, tested positive for the coronavirus during his final prep for Japan. Six hours later, an even bigger name dropped. Rahm had tested positive with his third and final test required for travel to Japan. He was tested three more times, according to the Spanish Golf Federation, and each came back positive. This less than two months removed from a positive test that pulled him out of the Memorial Tournament after 54 holes, and just weeks after a slew of negative results in his trip to England and Scotland.

Rahm was replaced by Jorge Campillo, the 205th-ranked player in the world. DeChambeau’s void was filled by Patrick Reed, aka Captain America, but only after Patrick Cantlay and Brooks Koepka passed on the chance to be an alternate. It was a late but important reminder of the opinion many top male pros have of the Olympics. As a result the field will forever be remembered as less than it could have been. One more major withdrawal would have leveled the strength of field with 2016. Some progress, but not much.

What does the future hold?

Whatever fervor is lacking among some of the best male golfers in the world is made up for by endless excitement from the women’s game, as well as the men’s competitors who actually made it to Tokyo. Paul Casey called his qualifying one of the greatest accomplishments of his career. His fellow countryman, Fleetwood, was thrilled when other English golfers passed up on the opportunity. Two incredibly talented South Koreans are playing for an exemption that will keep them from mandatory military duty. India’s Anirban Lahiri was one of the last men in the field, and he couldn’t be more excited to be here. He’s also in great form, so you never know.

Thomas, one of the betting favorites, was asked a tricky question about it all Wednesday. Where would he rank winning Olympic gold among his other career accomplishments? He pointed out that, with fewer chances, an Olympic medal might actually be more difficult to win. Especially for an American, as you’d have to be ranked in the top 10 in the world just to qualify. Could Olympic gold possibly be as important as a major championship? It’s going to take some time to figure that out.

“Major championships change your life in more than one way,” Thomas said. “I think this being as new as it is, I think potentially down the road it could be a different answer just because it hasn’t been around long enough to necessarily be in history books, if you will. Majors have been around long enough to where you’re, I hate to say, not judged, but your career is made off of them. So I think there will be a point in time where the amount of medals or gold medals that you have could be something that’s on that list.”