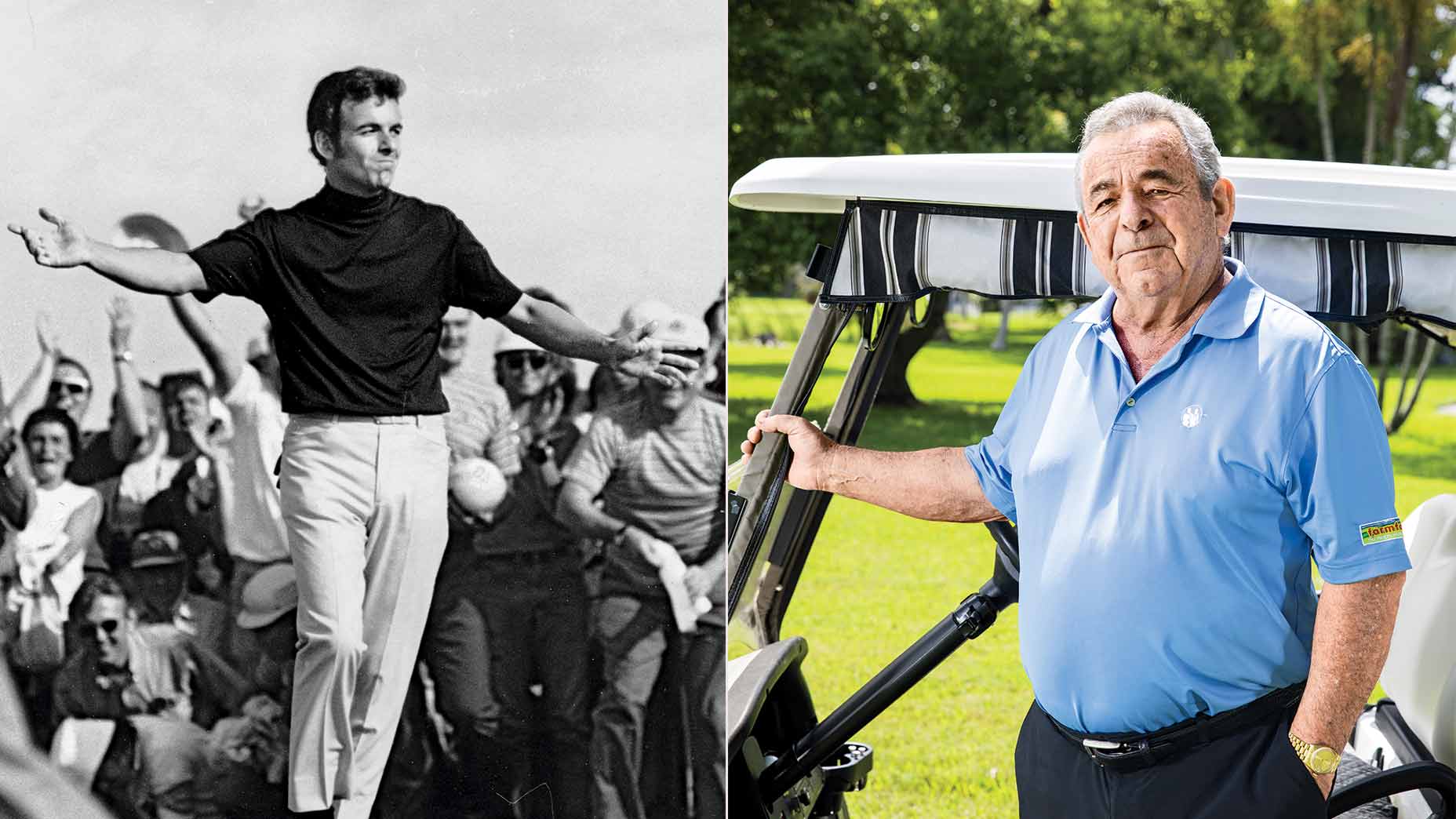

Fifty years ago, Tony Jacklin capped a searing season of golf by winning the U.S. Open, his second major in 11 months. Back then, the raffish Englishman looked Bondian cool, but a half century later he can still feel the frayed nerves — and just about every other emotion from his remarkable life in the game.

Tony Jacklin was not the fifth Beatle — it only seemed that way. In the late ’60s, the dashing Englishman with a great head of hair came to America with the goal of being the best golfer in the world. For a brief, brilliant moment he was, winning the 1969 Open Championship and the 1970 U.S. Open, with a transcendent performance at the ’69 Ryder Cup in between. Jack Nicklaus’ final-hole concession to Jacklin at that Cup — allowing the underdog Brits to forge a tie — is a lasting monument to sportsmanship and led to a lifelong friendship between the two men. Jacklin was unable to sustain the magic as a player, but in the ’80s he reinvented himself as the European Ryder Cup captain, leading the charge that turned a lopsided exhibition into one of the most intense spectacles in sport. In 2002, he was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame.

Now 76, Jacklin makes his home in Bradenton, Fla., the patriarch to four children, two stepchildren from his second wife, Astrid, and 14 grandkids. Jacklin has designed dozens of golf courses (including a joint effort with Nicklaus: The Concession Golf Club, in Bradenton), but this man of myriad interests is also a fine woodworker, the coauthor of a golf-themed novel, Bad Lies, and…a talker.

GOLF: Can you believe it’s been 50 years since your U.S. Open win at Hazeltine?

TONY JACKLIN: I don’t know where the hell the time goes! [Laughs] It’s crazy. But it was a great week in my life. From a golfing standpoint, I walked on water.

What was your secret?

The day before the tournament started I got a great tip from Bert Yancey’s brother Jim. He was a golf pro, and he knew I was struggling with my putting. It was a simple thing. He said, “Have you ever tried looking at the hole while you putt?” I threw three balls down on the practice green and, boom, I got this wonderful feel for distance. That’s how I practiced all week, though in the tournament rounds I returned my eyes to the putter. But I kept the feel. In the first round it was blowin’ 40 miles an hour. I was pretty used to that, playing so much golf in England and Scotland, but it seemed to affect everybody else. On the first hole I made a 20-footer, and I was off and running. I just putted beautifully all week. I thought my life had changed forever. I thought I was gonna putt like that every week. [Laughs] That wasn’t the case. But it certainly happened at the right time for me.

In the second round you hit a celebrated shot on the 17th hole. In the rough after an errant drive, you hooded a 5-iron and played a low runner around a tree that fed between two ponds and trickled pin-high, leading to a birdie. Why take such a risk when you already had the lead?

I remember it clearly. It was a risky thing. Playing links golf as much as I did, you’ve gotta visualize the shots. Imagination is half the game. And sometimes you have to seize the moment. That’s part of being a pro. You calculate the risk.

You increased your lead each day and entered the final round up by four strokes. How did you feel before teeing off?

I was about as nervous as I’ve ever been. I knew I had to get it done, otherwise I’d be branded a failure. There was a little bit of panic on the front nine. I three-putted the 7th hole. Then on No. 8, I hit a 4-iron to three feet, and I missed it! I thought to myself, Please, God, not now. On the next hole I had 30 feet for birdie, and I hit the putt far too hard. It could have rolled 8 or 10 or 12 feet past, which probably meant another three-putt. But my ball hit the back of the hole, jumped up about a foot in the air and decided to go in. And from that moment forward I thought, This is mine now.

You were the first European winner of the U.S. Open in nearly 50 years. Why such a long drought?

Very few of us ever came over here to play. But my ambition was to be the best player in the world, and I knew that if I was gonna be as good as I wanted to be, I had to beat the likes of Nicklaus and Palmer and Trevino. So I got my Tour card in 1967. Being in America, my game really accelerated. I became close to Yancey and Tom Weiskopf. Tom’s mentor was Tommy Bolt. I had played with all the best players we had in Britain, but they didn’t know as much about the golf swing, particularly the importance of the lower body, the legs. We were compromised by the weather and the links courses; it wasn’t about making swings, it was about playing shots, you know? But in America, I had the opportunity to work on technique. Weiskopf had that wonderful swing and he initiated the downswing with the legs, which was what Hogan and Nelson did — all the great players, really. And Bolt was our link to them. So I worked really hard on that. And winning in Jacksonville [at the Jacksonville Open Invitational] in March ’68 was a big deal because I played the last day with Arnold. Playing in front of Arnie’s Army was like playing with Jesus Christ. [Laughs] I mean, they didn’t give a damn about what you were doing. And despite that, I got it done. And that was a great confidence booster, knowing that I could win in that type of arena against all odds. I had to be tough playing over here, because there were a bunch of guys who resented any foreign player in those days. Fifty years is a long time ago — the attitudes were a bit different then. It was a battle to survive. When I stepped on the golf course, the softest thing about me was my teeth. This game gives you so many hits in the gut. You’ve gotta be tough to be out there week in, week out.

Your father was a truck driver. Is that where the toughness came from?

We never had much growing up. But my dad was a keen golfer and he gave me that love for the game. I was out on the British tour when I was 19. In fact, I was the first one in Britain to play golf solely for a living. Peter Alliss and all the rest had jobs to go to in the winter. But from 1963 forward, I went to South Africa in the winter to play. I went to the Far East. I just had a burning desire to succeed. I suppose some of that comes from growing up in very modest circumstances.

How did you pay for all the travel?

I had to play well! The ’63 Open [at Royal Lytham & St. Annes] kick-started my career. Making the cut there was a big deal at the time. That money kept me going for a while. Lytham was always good to me. I won a tournament there in ’67 and, of course, the ’69 Open [Championship].

I’ve been fortunate in my life. I wanted to win one tournament my whole life, and it was the Open. And to get it done so young, at 25, is quite amazing.

How were you received by the galleries at that Open, since you’d been spending so much time in the U.S.?

The British galleries were there to greet me. I could sense there’d been a lot of people following my golf through the media and that maybe they were proud of me. I had a tremendous following, even in the practice rounds. And I suppose you’re 25, you’re full of vim and vinegar and you want to show off. I got off to a nice start and kept going. I played well all the way through and others faltered. When you add up the scores, I had won by 2.

You make it sound easy, but I know the night before the final round you took a sleeping pill.

[Laughs] And Yancey had to put me to bed! I had dozed off in a chair. Look, I knew it was so important to sleep. There was a lot at stake. I knew there had been no British winner [of the Open] for 18 years, since Max Faulkner at Portrush. And we didn’t tee off until about 2:30 in the afternoon, so the last thing I wanted was to not sleep and be up bloody early, worrying about the round to come.

Had you taken sleeping pills before?

No. But I’ve taken a few since. [Laughs] You know, when it’s all said and done, the hardest thing is to stay in the moment. On the 14th hole [of the final round] I hit a good drive. Walking down the fairway, I said to myself, “I wonder if an hour from now, I will be—” And I actually physically smacked myself in the face. [Laughs] I was doing exactly what I knew you were not supposed to do.

An hour later you were the Champion Golfer of the Year.

I’ve been fortunate in my life. I wanted to win one tournament my whole life, and it was the Open. And to get it done so young, at 25, is quite amazing.

I wrote to him afterward and said, You know, that gesture was something that’ll stay with me for the rest of my life.

And then, two months later, you were part of an iconic moment at the Ryder Cup, with “The Concession.” People remember Jack’s grand gesture on that final green at Royal Birkdale, but not that you eagled the 17th to square the match.

That was a 50-footer, from here to eternity. [Laughs] I think people also forget I beat Jack in singles that morning. But, anyway, we got to the 18th tee of the final match. I’m hurrying off the tee, up ahead of Jack, eager to get to my ball. And he hollered after me, “Tony!” So I waited while he caught up to me. And he put his hand on my shoulder and says, “Are you nervous?” And I say, “Jack, I’m bloody petrified.” He says, “Well, if it’s any consolation, I feel the same way.” And it put it all in perspective. We both hit good shots into the green, leaving around 30 feet. I putted first, to within two feet. I had in mind that if he hit his close, maybe we’d say good-good, but he smashed his four and a half feet by. I couldn’t concede that! It was big-time missable, given the circumstances. While he’s hitting his final putt, I’m thinking, No matter what happens, TJ, you gotta make this goddamn putt. Like the great champion he is, Jack holed his putt. As he bent down to get his ball, he picked up my coin and said, “I don’t think you would’ve missed it, but I would never give you the opportunity in these circumstances.” Which was fantastic. We were already good pals, but I wrote to him afterward and said, You know, that gesture was something that’ll stay with me for the rest of my life.

I have to ask you about a less happy memory: the ’72 Open Championship at Muirfield.

There’s not much to say: Trevino chipped in five times that week. How do you beat that?

And yet you were tied playing the 71st hole, a par 5. Then what happened?

I was just in front of the green in two, and he was over the back in four. He ended up making five and I made six. It’s difficult to get your head around that. It was a big blow. I’m not sure I ever recovered.

But you were only 28!

I was very burnt out. I had been running myself ragged. Mark McCormack was representing me, and he was always pushing for more. I was traveling between the U.S. and Europe six or seven times a season. I was going to Japan and South Africa, always chasing deals and tournaments. I wasn’t living life on my own terms. It was never about what was best for me, it was about Mark and [his agency] IMG. It took me a long time to realize I was just a pawn in a much bigger game. The [’72] Open was a hard knock. And around that time the European tour was just beginning. I had a house in Northern England and a young family, so I decided I wanted to be closer to home. I guess you could say I lost my edge. I won some smaller tournaments after that, but my best golf was behind me.

And yet you had the ultimate encore, at PGA National, as Ryder Cup captain. How did you get the job in 1983, when you were only 39?

Historically, the captain was a generation or two older than the players; it was an honor given to somebody well after their playing career ended. I didn’t find this out until much later, but Bernhard Langer and a couple of other younger players on the tournament committee kept arguing that they needed a captain who was more in tune with the players. They kept going back and forth, and five months before the Ryder Cup they still hadn’t named a captain. They finally called me. You could have knocked me down with a feather. But I knew things had to change, so I said I would only do it if they gave me carte blanche. I wanted us to fly on the Concorde, just like the Americans; we had always been on the back of the bus on British Airways, not knowing who was paying for the drinks. I insisted we get to take our caddies — that hadn’t been done before, because of money. I demanded a team room. We’d never had that before. All of our meetings were in the back of these smelly locker rooms, and then we had to go out and find dinner in whatever town we were in. And I said I had to have Seve. [Ballesteros, the 1979 British Open and ’80 Masters champ, had been snubbed for the ’81 Ryder Cup team because he was feuding with the European tour over appearance fees.] Lord Derby, who was the president of the European PGA, said, “You’ve accepted the captain’s job. He’s your problem now.” [Laughs]

Europe had lost every Ryder Cup since you helped forge the tie in 1969, and most of the losses were blowouts. But in 1983, you pushed the U.S. to the brink before losing by a point. What changed?

It starts with the players. Seve, Faldo, Lyle, Langer, Woosie — this generation was about to start dominating on the world stage. And then we created the environment for them to succeed. What I was really doing for them was giving their self-esteem back. They all felt like kings. They were being treated properly. And we came bloody close to winning. Afterward, we were all taking it quite hard. It hurt to come so close and not pull through. It was Seve who spoke up, and said we had a lot to be proud of. I think he knew in his heart things were going to change.

Indeed, because in 1985 Europe won for the first time 28 years, and it wasn’t close. How good was that celebration?

Well, I had bought all the guys these beautiful Savile Row suits, and they all ended up wearing them in the bloody swimming pool at the Belfry!

Now in ’87 you have to tangle with Jack again — he’s the U.S. captain and the Cup is at his lair, Muirfield Village. You guys had a big lead going into Sunday and then the U.S. won five and a half of the first seven points in singles to essentially tie it up. Have you ever been more nervous in your life than you were at that point?

The short answer is no. As captain, you make your decisions and then all that’s left is to pray. [Laughs] I know I was asking God for a few birdies. The captain’s job is so nerve-racking, and thank goodness we pulled through because I might not have survived it if we didn’t.

That was the first European victory ever on America soil. Not many people can say they have something on Jack Nicklaus. That has to feel awfully good.

Well, Jack has always been a great sport, and he was then, too. It’s certainly a special memory. I loved everything about being Ryder Cup captain. So many great moments and great friendships. It’s fun to talk about all of these things, even the heartbreaks. I’ve had a great life in golf. It was a fantastic adventure and I wouldn’t change it for the world.

Tony Jacklin by the numbers:

Professional debut: 1962

Total professional wins: 29

European Tour wins: 8

PGA Tour wins: 4

Major championships: 2

Senior PGA Tour wins: 2

Ryder Cup appearances: 11 (4 as captain)

World Golf Hall of Fame induction: 2002