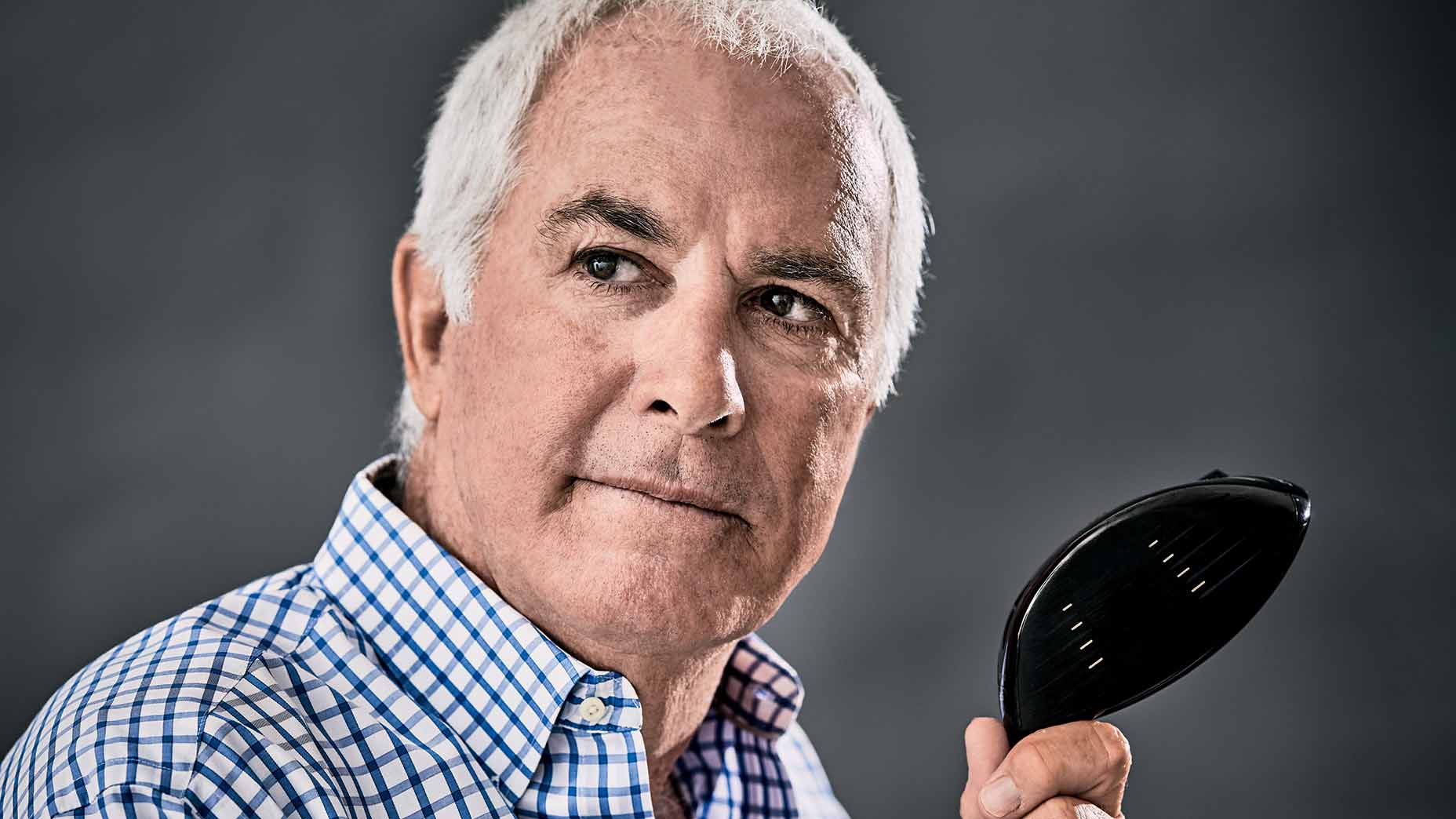

You’ve been tracking Curtis Strange for decades now. In the 1970s, when you were shooting frozen-fingered, nine-hole 47s in your high school matches, Curtis was shooting 68s for Wake. He was a golfing god, and he and his brickhouse Wake Forest teams got regular write-ups in Golf World (a weekly and a bible), in Golf Journal (a USGA publication) and in all the better dailies. Curtis Strange was a national golf figure at age 20. Now he’s 67.

Somehow life has conspired to put you in a place where you get to talk to Curtis on a semi-regular basis. You’re on the phone with him, you see him in hotel lobbies, you walk beside him at tournaments, in reach of the rope line. You’re actually comfortable around him. But this moment is different. Now you’re in Curtis’ real office. Curtis Strange, on a range, club in hand. Once it was an everyday thing. But you haven’t seen it in years.

This practice tee is at a course called Grey Oaks in South Florida, near a winter home Strange shares with his wife of 45 years, Sarah, and (when they come through) their two grown sons and five grandchildren. As a commentator on TV and radio, Strange is incisive and candid. As a player, he was the same way, appealingly so. That was once a characteristic of U.S. Open winners. Ben Hogan, Hale Irwin, Hubert Green, Larry Nelson, Raymond Floyd and Tom Watson come readily to mind. DIY golfers. Flinty, really.

Curtis is making his familiar move, even though it’s been 33 years since his last significant win — the 1989 U.S. Open, which came a year after his win at the 1988 U.S. Open, at The Country Club. “Peter Jacobsen had the best line,” Curtis says. “‘What, they couldn’t come up with a name?’”

As Tour rookies, Curtis and Sarah and Peter and his wife, Jan, once found themselves staying at a place called Edge of Town Motel. They grilled their dinner on a portable hibachi and figured out that some of their neighbors were renting by the hour. If you get a chance to talk to Curtis, seize it. He’s a living link to the Tour when it was still a tour and people lived on it.

And now, at his invitation/insistence, you’re hitting balls right beside him, or trying to. Curtis is hitting it on the face, of course. Your own strikes are thin and thick and left and right. And then Strange decides to take a break from his own pile. He stations his slender self behind you and says, “Let’s see what you got.”

Must we?

Whatever Curtis Strange says about the game, it comes from a deep place. Although he’s a son of the South, and although he took a four-shot lead as he made the turn on Sunday at the 1985 Masters (Bernhard Langer won), to Curtis the U.S. Open is the father of all golf tournaments. His own father, a club pro who died before turning 40, played in six Opens. “I knew that the Masters was a special tournament, but it was an invitational. Anybody could play their way into the U.S. Open,” Curtis will tell you. Big difference. Augusta was cozy and clubby and private. The U.S. Open had narrow fairways but was open in every way.

So it is with pain in his heart that Curtis acknowledges that the Masters has become the it event for many players. “I don’t know when that happened, but it did,” Strange says. He can readily list the various things the Augusta lords have done right over the past 20 years, and the various missteps by the USGA: some of the courses USGA officials selected for U.S. Opens. Some of their rulings. Some of their hole locations. Some of their broadcasting decisions. Life turns on little things.

“The U.S. Open lost its identity as the hardest event in golf,” Strange says. He believes the USGA can get its groove back. He hopes the USGA can get its groove back. He has considerable skin in the game. He was the medalist at the USGA junior boys’ event in 1971. U.S. Opens were holy days for him and still are.

“The June days were so long, and you could practice so late,” Curtis says. He always lived on the range. He was always happy on a range. Dusk would come, at The Country Club, among other places, and Curtis would be over his pile. Sarah would often be 10 feet away, sitting on his bag. Curtis, both his game and his mentality, was made for the U.S. Open. After winning in ’88 and ’89, Strange still had a chance to win with nine holes left in ’90 at Medinah. A chance to win a third in a row. Hale Irwin won. It was his third Open title, 11 years after his second. Sarah and Curtis and Curtis’ twin brother, Allan, flew home from Chicago in a small private plane. The fellas drank beer and the plane had no lavatory. That was the least of it.

“It was terrible,” Sarah Strange says of that flight, and that period. “We were completely wiped out. The whole buildup to that third Open took Curtis out of his element.”

Allan’s sense of it is different. He feels that there was a certain relief for Curtis, when the run was over. He reminds you that in 1994, at Oakmont, Curtis played great, shooting four rounds of 70. He was one shot out of the Ernie Els-Loren Roberts-Colin Montgomerie playoff.

And then there is Curtis’ take on it, on what his golfing life was like, after Medinah. “I lost the edge,” he says. “I still went to the range, but it wasn’t like it was.” The intensity of his sessions and what they meant to him. The heat of his internal fire. No thermostat is refined enough to measure his before and after temps. But Curtis could tell the difference.

Curtis continued to go to the range. He continues to go to the range. It’s his sanctuary. Does he expect to suddenly get better? No. But he knows what every lifer in the game knows. There’s a deep pleasure in trying. Because golf is hard, and it feels good to do a difficult thing well.

So Curtis is behind you, on this range in South Florida. He takes an alignment stick and puts it in the ground about three inches behind and three inches to the right of your striped ball. He angles the stick so that it’s at about a 45-degree angle, roughly pointed at your chin.

“I can’t tell you what to do,” Curtis says, “but I can give you a sense of what it should feel like. Go ahead and hit the ball. Just make sure you don’t hit that stick.”

You make a backswing and a downswing. You clear. The strike is on the face and the ball is up in the air and drawing.

Without the stick, Curtis says, you’re too upright and to outside.

The next one’s good too.

The next round’s good too.

You report your progress to Curtis by phone.

“Next time I see you, we’ll have to set up the stick on the other side,” Curtis says. “You’ll be too inside by then.”

He knows how this thing goes, to the degree it’s knowable at all. Curtis Strange will tell you: It’s not knowable at all. And he wouldn’t want it any other way. Would you?