You already know Brian Doxtator.

You met him for the first time last month at the 149th running of the Kentucky Derby, as the pack charged down the home stretch at Churchill Downs. Doxtator stood at the front of the group suddenly in NBC’s crosshairs, wearing a pastel suit and a white hat. His company’s horse, Mage, had just crossed the finish line in front of him, winning the Kentucky Derby. He jumped up onto the railing in celebration, deliriously yelling and hugging his salmon-suited counterparts in front of a flock of NBC camera lenses.

Almost immediately, the image of the three frat-adjacent men on the verge of tears went viral. For a few hours, Doxtator was the face of every meme on the sports internet. Not that he realized.

“As I walked out of the trophy ceremony, someone turned to me and said, ‘Have you checked your phone?'” Doxtator told GOLF.com. “And I was like, ‘I just looked at it. I have a ton of texts and calls. It’s pretty crazy.’ And they said, ‘No, Brian, check social media.‘”

He opened Instagram.

“That was the first moment where it hit me,” he says now. “Oh boy, everything just changed.”

What changed in the instant Mage crossed the finish line at the Run for the Roses? For one thing, the trajectory of Doxtator’s professional life.

Today, Brian Doxtator is the co-founder of Commonwealth Sports, a sports startup aimed at turning athletes into assets. Through his company and associated app, users can invest money to purchase real pieces of “ownership” of professional athletes. When Commonwealth’s athletes make money, its shareholders earn a piece of the pot, too.

It is an idea of a decidedly different flavor in the sports marketplace, where ownership opportunities have long been left to only the highest-income earners. At the Derby alone, Mage’s victory earned profits of some $93.54 per share for some 400 owners who purchased $50 shares in the horse’s fundraising round. And if you believe Doxtator, that’s only the beginning of it. His goal is to “democratize” sports ownership, making it affordable to real people to “invest” their money in athletes of all sports, hopefully providing real-life financial incentives to those who do.

“We’re hoping we can create a virtuous cycle,” Doxtator says. “Our company is battle-tested. We’ve won big races. We had the highest-earning horse in the world last year. But this thing is just as much on a personal level as it is on a financial one.”

Eventually, he says, he dreams of Commonwealth as a sort of sports utopia, where successful athletes beget further investment — and buy-in — from shareholders, building a community of hybrid fan/owners making money and memories following athletes.

“We had a ton of people in Miami for a race in January. We had a suite at the Genesis Invitational,” he said. “We were joking that when we do a fundraising round for our next horse, we’re just gonna post photos of our owners holding trophies at the biggest races in the world.”

But creating a sports utopia is about more than picking the right horse; it’s about picking the right horse over and over again. Lost in Doxtator’s bluster is the cold reality of the business he’s chosen: it only works if Commonwealth keeps winning.

To date, Commonwealth’s success can be largely tied to the racing expertise of Doxtator’s partner, Chase Chamberlin, who aligned the company with the racing blueblood Winstar Farm and helped steer it in the direction of Mage. But Doxtator seems to understand the next move he makes — expanding Commonwealth’s offerings into a second sport — could be even more important to the company’s long-term success. This is perhaps why Commonwealth’s second sport is the one closest to the founder’s heart.

“Golf,” he said. “I’m a lifelong golfer, a scratch player. I played competitive amateur golf. I mean, I’ve got a golf club sitting next to me right now.”

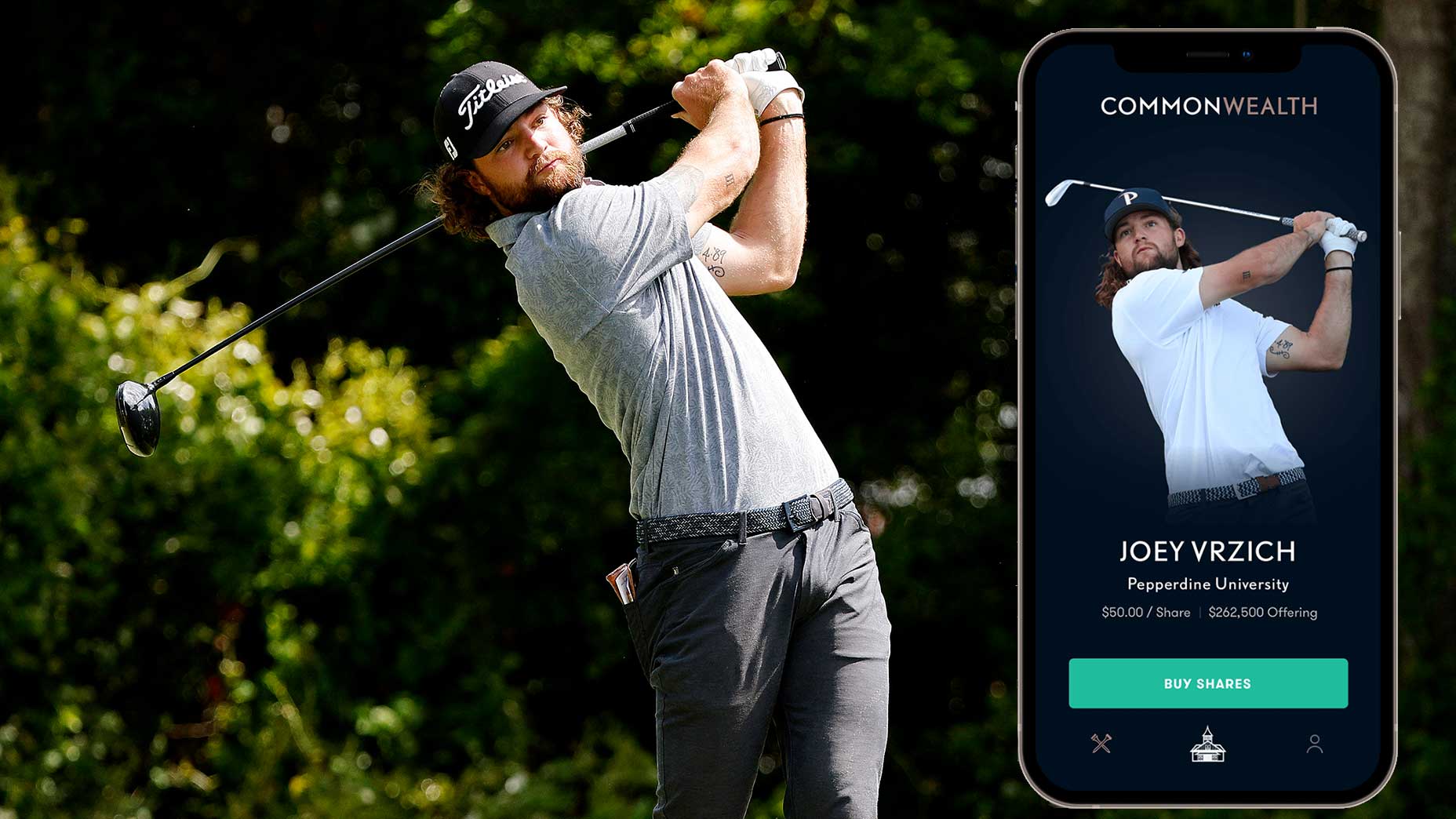

Brian Doxtator didn’t need to watch Joey Vrzich play a hole to know that he was the “real freaking deal.” In fact, he didn’t even need to watch him hit a shot.

It was during an afternoon round at his home course, the Saticoy Club in Somis, Calif., that Doxtator and Vrzich first crossed paths. Doxtator was on the 17th tee box when Vrzich’s group — a foursome of teammates from the Pepperdine golf team — hit into him.

“They’re walking up, and Joey’s coach comes up to us and says, ‘Hey guys, sorry about that,'” Doxtator remembers. “We’re like, ‘Hey, no worries, how are the guys playing?'”

Vrzich’s coach pointed in Joey’s direction.

“You see that guy with the long hair in the middle of the fairway?” The coach said. “He’s eight under.'”

Doxtator was hooked.

“I was like, oh my god. Saticoy is one of the hardest-scoring courses I’ve ever played,” he said. “I got his name and started researching him. I loved his resume. I loved his game. And then I got in touch with his agent and asked him if he wanted to sign.”

The agreement was fairly simple. Commonwealth agreed to pay Vrzich a one-time sum of $257,000, which is expected to cover three years’ worth of travel, caddie and coaching expenses, in addition to other odds-and-ends. In exchange for that investment, Vrzich agreed to pay out a percentage of his earnings to Commonwealth for the next six years. In the first three years, 30 percent of player earnings are paid out to Commonwealth investors, and in the three years following Commonwealth’s investment (years 4-6), investors earn steadily decreasing shares of player earnings (20 percent, 15 percent and 10 percent). At the end of the sixth year (or at any point in the agreement, provided Vrzich is willing to pay a buyout provision) he can return to keeping 100 percent of his earnings.

For a player, Commonwealth offers an enticing opportunity: three years of guaranteed job security at a time in which payouts are infrequent and growth is significant.

“If you were on a one-year deal, imagine halfway through and it’s not going well — you can’t make a leap on a one-year deal,” Doxtator said. “We want our guys to take the long approach. Don’t cut corners. Do it the way you believe is putting you in the best position to succeed.”

For prospective investors, Commonwealth ownership is even easier. Once Doxtator and a team of advisors have purchased a “position” (an ownership stake in a racehorse or revenue-sharing agreement with a professional athlete), Commonwealth offers the position to the public in what’s called a “single-asset equity.” Once the SEC approves the arrangement, Commonwealth divides its ownership into shares, then offers those shares for purchase through the company app. Most users can purchase a share in an athlete or racehorse in less than a minute. (As a carrot for serving as the intermediary, Commonwealth takes 10 percent of investor revenue, but Doxtator has been known to invest personally in many of Commonwealth’s offerings.)

Share price is affected by two primary factors: earning potential and user interest. Some shares are priced higher — around $1,000 per share — for a higher potential gain. Many are lower — around $50 — the same amount Commonwealth priced Mage. Doxtator says the goal is to bring most of the company’s offerings closer to that $50 number, but that will depend upon the number of active users the company can attract.

“User growth is a key metric for us because we can get more sports assets and offer more opportunities,” he said. “And then of course, the community is bigger and we can activate them more often.”

Mage’s victory was Commonwealth’s highest-profile success story to date. On the Commonwealth app, user accounts more than doubled after the victory, ballooning to some 15,000. The attention Mage — and other profitable horses — have earned has helped to fuel belief among Doxtator’s colleagues that the company is on the precipice of a sports fandom revolution.

“Racing is set,” he says, “Everybody agrees. Racing is good. We’re gonna try to make it bigger. We’ve got to.”

Golf will be the first foray in bringing Commonwealth to the big-time, and Vrzich will join Baylor grad Cooper Dossey in leading the charge. The two golfers — Vrzich is 24, Dossey 25 — have full status on PGA Tour Canada for 2023 and will be part of the end-of-season push toward the Korn Ferry Tour. As part of their agreement, both golfers are contractually obligated to wear Commonwealth logos and provide weekly “shareholder updates” on the company app, in addition to regular contact with Commonwealth officials to ensure proper use of the shared bank account holding the initial investment. That said, Doxtator indicated player discretion remains pretty broad.

“All we’re doing is reviewing expenses at the end of every month,” he said. “So long as you can say, ‘Hey, this is why it’s related to my golf career,’ we will almost certainly approve it.”

It’s early to say if either has what it takes to wind up on the PGA Tour, but it is decidedly not too early to earn a piece of their success. Commonwealth is expecting to release an “IPO” on both players — expected to be priced at $50 per share — in the coming weeks.

“All I’d say is I’m not just a business guy doing this. I live on golf courses. I try to hear the inside scoop from the money games, from the agents,” Doxtator says. “We’re looking for people who fit our company.”

Mage lost the Preakness, the second leg of the Triple Crown, a reminder that even Commonwealth’s best assets often result in no payout for the folks at home.

Still, the Derby video still proved a surprising dose of fame for Commonwealth Sports. On the heels of the most significant win in the company’s history, public interest in the startup exploded overnight. Doxtator, whose original background is in venture capital, says the timing couldn’t have been more serendipitous.

“I always say, the startup graveyard is littered with companies that had their moment too early,” Doxtator said. “We started in 2019. We were two years in stealth. We built our platform and now here we are, battle-tested.”

That might seem like a strange thing to say about a three-year-old startup (largely because it is a strange thing to say about a three-year-old startup), but when Doxtator sees that Derby video, he sees something more than a few pastel-colored suits and a celebration.

“Shortly after our video came out, I got sent a video of some friends on a golf trip in Palm Springs watching the race. None of them were invested in Mage. None of them have even invested in Commonwealth. But they took a video of them losing their minds when Mage won, and that was the moment that I burst into tears,” Doxtator says. “I just got emotional and couldn’t believe it, because it was just the ripple effect of what’s going on. Clearly, it’s all working.”

It is working. There’s just no guarantee it’ll keep working. The randomness of competition is one of the great joys of watching professional sports, but it’s easy to see how that same randomness could prove disastrous for a company hoping to turn athletes into commodities.

Informed as Doxtator’s read on Vrzich and Dossey is, they’re still long shots to reach the PGA Tour, let alone the sustained level of Tour success needed to represent a massive return on investment for shareholders. Players from the PGA Tour Canada and Latinoamerica (which were recently combined under the Tour umbrella) make up just 28.2 percent of the current PGA Tour constituency. The vast majority arrive directly through the Korn Ferry Tour, PGA Tour University, sponsors and special exemptions or some combination of the four.

But then again, if the goal is to build a sports community, Commonwealth might not need to generate eye-popping ROI to capture sufficient interest from sports fans. For that, it needs only a few more moments like Churchill Downs.

“The Derby was the best big moment, but we don’t want just one big moment. We want a whole team full of them,” Doxtator says. “And I’d say after the Derby, that’s no longer bluster. We might have a claim to be the most exciting team in sports.”

There’s no shortage of bluster, either. Still — what if he’s right?