The actor Paul Giamatti was born in 1967. So was the country singer Faith Hill and Kurt Cobain, the late Nirvana frontman. The CNN anchor Anderson Cooper was born in 1967. And the golfers Steve Stricker (517 PGA Tour starts), David Toms (617 PGA Tour starts) and Brian Morris (one PGA Tour start). Morris played last week, in the Bermuda tournament.

Maybe you saw glimpses of him there, at the Butterfield Bermuda Championship. Golf Channel showed him some. So did the Tour’s social-media channels. Or maybe you were one of the few dozen people following him around the gorgeous Port Royal links. We could all see the hold this game can have on a man.

Morris knows the deal. “One and done,” he told me the other day. He had played 36 holes in a PGA Tour event and he won’t be playing in another. He had to play out of a cart. That gnawed at him. But there was no way his body could tolerate two straight days of walking.

His scores — 89 and 92 — were the least of it. He got himself to the first tee on Thursday and to the 18th green on Friday. That was the most of it. He got through the one part of one and done. Like Archie “Moonlight” Graham, who is in the Baseball Encyclopedia for appearing in one game, in 1905, as a New York Giant. He never stepped into the batter’s box but he stood in right field for a half inning and that was enough. And in that vein, Morris is a note in the PGA Tour’s record-keeping. One start. Yes, one MC. But one start!

At the start of the first round, he had an odd sensation. From the time he hit his opening tee shot until he pulled his ball out of the first hole, he felt nothing. It wasn’t the accumulated weight of his 30-plus chemo treatments. It wasn’t his neuropathy. It was the adrenaline coursing through his veins. For a short spell there, he was Superman. His slight flesh-and-blood body had turned to steel. His P-for-Puma hat could not contain his head.

A month earlier, Morris, the head pro at the Ocean View Golf Club, on Bermuda’s north shore, had called his wife from work. For a moment, she heard only his sobbing. Suddenly, a thousand invisible bugs were crawling all over the inside of her skin again, spreading anxiety with ruthless efficiency. Her husband, father to their four children (blended family), has Stage IV cancer. It’s in his stomach and esophagus and brain. He has inoperable tumors in his neck. Laurie Morris has learned to fear a buzzing phone.

This time, the news was good. Butterfield, a Bermuda bank with ledgers going back to the 18th-century, was giving her husband an exemption into the PGA Tour event it sponsors.

A fast month later, Morris was playing in the tournament with Sahith Theegala, a tall and lean 23-year-old Tour rookie from California, and Michael Sims, a former University of Rhode Island golfer and Bermudian. Morris and Sims are cousins, Bermuda-style. Only 63,000 people live on the island, and family histories are often all entwined. Each calls the other cuz.

(A quick and coincidental aside: I walked-and-talked some with Sims at Torrey Pines during a U.S. Open practice round, where he was caddying for a qualifier, Wilson Furr. Every year, the golf world expands. The game goes to new places. But it contracts, too. Someday I imagine I’ll see Tiger and Charlie at the driving range at the North Palm Beach muni.)

Sims got in the Butterfield tournament through a Bermuda qualifier, where there were two dozen locals playing for four spots. Sims (73, 77) didn’t make the cut in the tournament. Theegala, who had a superb college career at Pepperdine, did. He shot 140, even par, to make the cut on the number. “He put up with me,” Morris said. “Sahith, man — he’s got loads of game.”

Morris does, too. Ask Sims. Ask anybody who knows the intimate world of professional golf in Bermuda, where there are more than a half-dozen courses, a sizable number for a country that’s not that much bigger than Manhattan. The golf pros in Bermuda are like surfers in Santa Cruz. They hang. They move around. They do what they can to stay in the game.

My friend Mike Donald, the former Tour player and the winner of the 1995 Bermuda Open, has made more than 15 trips to Bermuda, to play in the Bermuda Open and the Goslings Invitational. Morris played often in those events, and Mike would see him, by day and by night. “He shot 29 one year on the front,” Mike told me. This was in the Goslings event. The years blend. “I saw it on a leaderboard and I’m like, ‘Holy sh*t — Brian’s having some round.” Out in 29 doesn’t mean you’ll sign for 63, of course, but you don’t just get lucky and shoot 29. Morris recalled leading after a 66 one year “and then choking in the next.” I could hear in Mike’s voice how much he loved Brian’s life-is-good vibe, to say nothing of his tell-it-straight manner. Mike painted a picture of a man who could tend bar deep into the night (Docksider’s, Front Street, Hamilton) and be on the first tee bright and early the next morn, cheerful and ready to go. Brian remembers some top-20 finishes.

He wasn’t playing for the hardware, not really, or even the check, though a check is always nice. Brian was in the game for the game. His favorite golfer is Fred Couples, though he’s never met him. His favorite tournament is the British Open, though he’s never played in one. His favorite course is the Old Course, though he’s never been on it.

His accent is chiefly British, with nods to Australia and Canada and the American South. “I believe in a body life,” he told me. He was explaining one of his many tattoos, this one on his left arm: LIVE LUCKY, the words separated by tumbling dice. “Every day you live, trust me, you live lucky, mate.” Troost me.

The Morrises, husband and wife, like Vegas. They like to gamble. They go every year with friends. Well, not every year. They didn’t go this year. Still: live lucky.

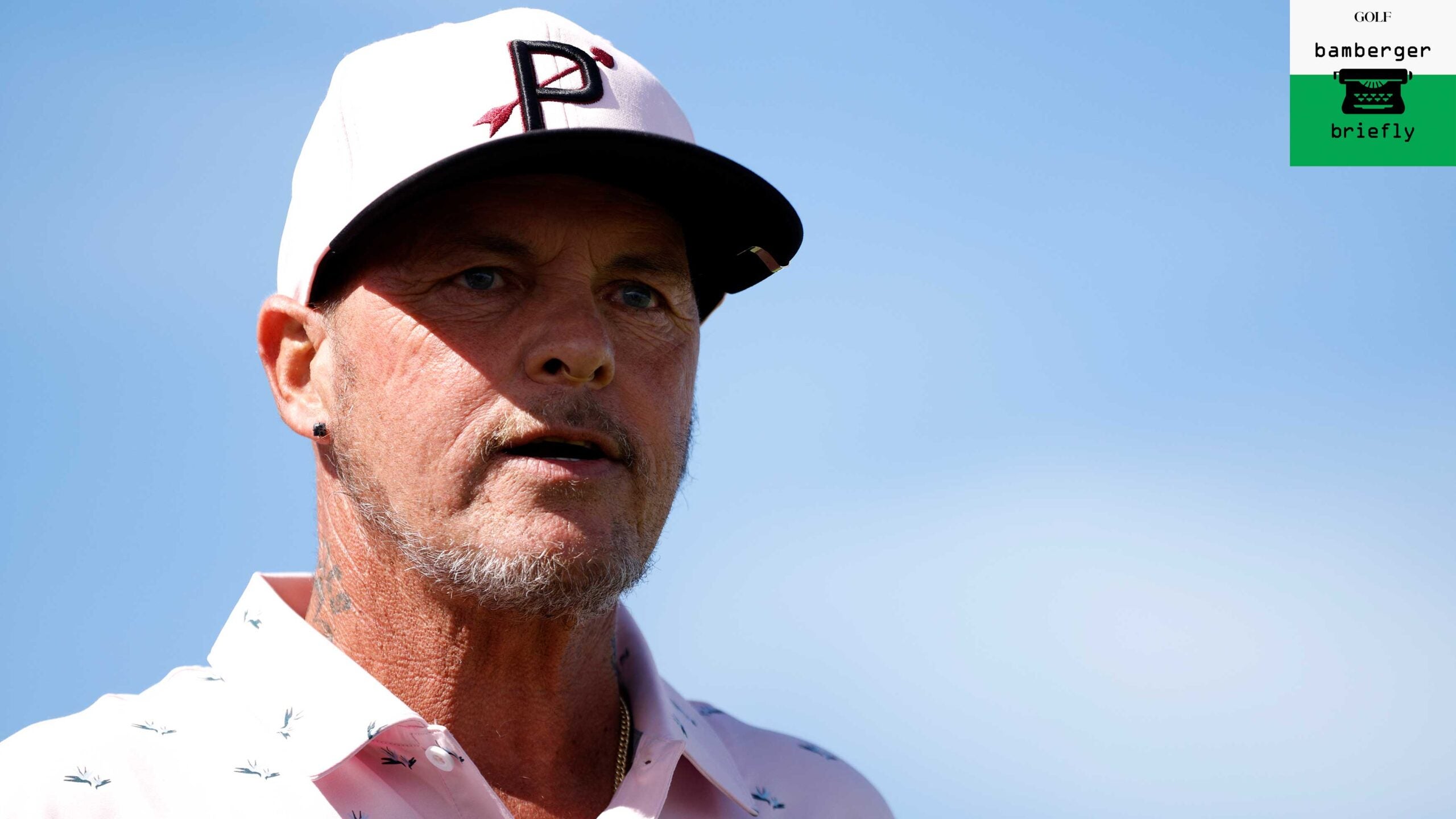

Brian has an interesting face. I mean, it’s right up there with Harvey Penick’s, who had creases on his so deep they could hold (people used to say) a seven-day rain. Brian has bright blue eyes and an impish, boyish face, save his wispy seafarer’s beard. He often has a long tee stuck behind one of his ears and there’s a black stud in his left earlobe and another in his right. He played his Friday round wearing a white shirt dotted with cartoon red-and-black monster trucks. A great shirt. It helps that Brian has the elfin physique, and matching spirit, to pull it off.

He also has a blue-ink tat on the left side of his neck that depicts the map of Bermuda. It’s a showpiece. Bermuda, as it dangles down Brian’s neck, looks like an old, sea-stained fishhook.

One of Brian’s heroes growing up was Keith Pearman, the longtime head pro at Mid Ocean, the island’s celebrated C.B. Macdonald course. Pearman, who died this year, was a revered golf pro and instructor, a beloved fishing guide and the one-man welcoming committee to thousands of Mid Ocean members and guests over the years. “As a Black man in Bermuda, in the golf industry, in his generation? Keith went through a lot,” Brian told me. “The perseverance he showed — I idolized him. One of the reasons Ocean View, my club, was built was so that Black golfers and Portuguese golfers could have a place to play.”

Every day you live, trust me, you live lucky, mate.

Ocean View is close to downtown Hamilton. It’s a sporty nine-holer, not even 3,000 yards long. Brian Morris, Keith Pearman, Michael Sims, Mike Donald and boatloads of other pros, local and visiting, have put up all sorts of low scores there, sometimes while playing under the light of the moon. (Full moons in Bermuda are especially bright. All that reflection off the water.) Sims played Ocean View with Brian earlier this year when his cousin made six or seven birdies over the course of nine holes. Something around 30, maybe lower, had anybody been keeping a card. But who needs a card when you’re playing match play?

Brian’s father — a few years older than Pearman on an island where everyone (kind of) knows everyone — was a 2-handicap golfer who sold life insurance. He started Brian in golf, among other sports. He wanted Brian to play as a righty, because right-handed clubs were easier to find. But Brian is nothing if not stubborn and he insisted on playing from the left side of the ball. He loved the game and imagined a future in it. He played in junior events and played well but his father was his main playing partner.

One day, when Brian was 19, his father came to watch him play cricket. (Bermuda takes many of its cues from Great Britain.) It was a usual thing. The father was sitting on a wall, about 20 feet off the ground, watching the cricket, when he fell, landed unlucky and died instantly. Brian saw it. His father was 49.

Some months later, Brian’s mother, after a brief bout with cancer, died. She was 49.

Some years later, Brian’s sister, who had profound disabilities and lived with their grandmother, died. She was 49.

Their grandmother was like their second mother. In time, and in her time, she died, too.

My mom, my dad, my sis, my granny.

Brian would like a reunion.

After his father died, he took his clubs, went to the top of a cliff and threw them to the beach below.

“I didn’t know how to play golf without my dad,” Brian said. “Golf meant nothing to me without him.”

Through his 20s, Morris was on a walkabout, Bermuda-style. He buried his golf dreams with his father.

“It was probably for the best,” Brian said of his leave from the game. “I wasn’t mature enough. Had I worked in golf then, I would have burned my bridges. Now I’m grateful for it.” He tended bar. For six or seven years he worked a 6 p.m. to 3 a.m. shift, then, as a father himself, he switched to days.

After about 10 years without any golf in his life, a childhood friend invited him to play. They had come up playing junior golf together. “I didn’t want to go but I did,” Brian said. “I made a triple bogey on the first hole and I realized how much I missed it.”

This is fuzzy but this is Bermuda: Brian’s father, as a young man, delivered candy out of truck. He hired a kid to help him. That kid grew up and landed in the golf business. He encouraged Brian to go to the Orlando campus of the Golf Academy of America and get an associate’s degree in golf management. Brian did and it changed his life. That was in 2003. He’s been working in golf ever since. He plays golf, his friends are golfers, he travels with his clubs and stays at golfy hotels. He leads a golfing life.

One of his tattoos depicts a Bentley, to honor his driving game, he said. He drives it right down the line, without any Fiat 500 wobble. His son, Brian Morris Jr., has a Bentley tat, too. Brian Jr. is 30 and loves ye olde game. Natasha is 29 and lives in England. Zachary is 27. Rico is 17. Brian’s foursome. Plus, of course, Laurie.

The family house is 70 or 80 years old, purchased from Laurie’s mother. Through a window, Brian can watch cruise ships sail on by, gulls hovering over their sterns. Those cruise ships are an important part of the Bermuda economy. There are golfers on the cruise ships, golfers who rent clubs and buy golf balls. A cash register must ring. It’s the way of the world. “With Covid,” Brian said, “we haven’t had a lot of cruise ships.” There have been lulls before.

His two days in the Butterfield event were exhilarating. Playing with Michael and Sahith, and in front of so many family members and friends. Graeme McDowell and D.A. Points, strangers, went out of their way to say hello, to send Brian their best. “They’ve been, they’ve done, they appreciate,” Brian said.

There’s a cryptic beauty to some of his remarks.

“It’s exciting to meet you,” Brian said to McDowell. McDowell won the U.S. Open at Pebble, in 2010, when Tiger, in a manner of speaking, was the defending champion.

“I’m more excited to meet you,” McDowell said.

Brian described his play on Port Royal’s 16th hole, a spectacular 200-yard par-3. The detail was glorious: “Ocean short, ocean long, ocean left, wind in your face, bailout right.”

What’d you do?!

“Nutted a 3-wood, right into the bailout area, both days,” Brian said. Smart golf. He made two 4s.

He’s had, by the way, four aces. He went 20 years looking for his first hole in one. Then he made three in three straight rounds, on a Thursday, a Sunday and a Wednesday. What are the odds of that? Completely, totally incalculable. He made another, his fourth, earlier this year, on the 2nd hole at Ocean View. Live lucky indeed.

Brian learned of his cancer diagnosis in 2019, a day before Christmas eve. The doctors told him blahblahblahblahblah. The doctors gave him six months. Well, he’s still here! When he holed out on 18 after the second round, Laurie was there, screaming and cheering and clapping and crying, along with scores of others. Sims had slipped out his phone and recorded the two-putt for posterity. “I never saw him smile like that,” Laurie told me.

In his prime, 150 would have been about the highest Brian Morris could shoot for two rounds at Port Royal. That is, in his physical prime. In other ways, he’s at his prime right now. His thinking is so clear. “I know this cancer is going to kill me,” he said. But it comes with a bright side. “Nothing pisses me off anymore,” he said. He looked around Port Royal and “saw so many of the people from my life.”

Let’s bring in the lads.

“In My Life,” from Rubber Soul, The Beatles, 1966:

Though I know I’ll never lose affection

For people and things that went before

I know I’ll often stop and think about them

In my life I love you more.

Music ran through our conversation. Lately, I’ve been on a kick of listening to Gerry Rafferty’s “Right Down the Line” and various covers of it. The song came to mind for me again when Brian was talking about his driving prowess and his Bentley tattoo. Golfers used to say, after splitting the fairway, “Right down the sprinkler line.” (From the era of a single mid-fairway irrigation pipe.) There’s a Bonnie Raitt cover of “Right Down the Line” that brings a reggae vibe to the song. Brian loves reggae. He loves Jamaica. (Jamaica and Bermuda are opposite sides of the same coin.) He’s been to Jamaica about 10 times. Bob Marley, Jamaican rasta king, lives on, in ink, on Brian Morris’s right forearm. It was his first tattoo.

“I believe you’ve got to travel, bro,” Brian told me. “I love Vegas. I love Jamaica, Australia, England. I love being anywhere, man. Even Canada. I love traveling, seeing the different cultures. It’s healthy to see.”

Golf has kept me grounded, humble. I would never apologize for how much time I’ve spent playing.

Brian said the illness made him appreciate life’s smaller moments. Man, does that hit home. Sometimes, just kicking in the edges of a divot hole after a good shot gives me so much pleasure I can hardly stand it. Brian talked about the pleasure of a warm bath in a big hotel tub, so big you can get your knees and your shoulders under the water at the same time. Talk about your post-round elixir.

I asked Brian if he considered his time playing golf time well-spent.

“One-hundred percent,” he said. “Absolutely, it’s time well-spent. Golf has kept me grounded, kept me humble. It’s given me the opportunity to meet some fantastic people. It gets you outside, with your peers, your friends, maybe your spouse. I would never apologize for how much time I’ve spent playing golf.”

I thought about that for a moment and said, “I’ve come to realize that golf is some teacher.”

“That’s well said,” Brian said. “It is. Golf is some teacher. Golf teaches you to adapt.”

There’s the game, in five words.

He plans on playing as much golf as he can, as much as his body will allow him, here on out. I asked: If you could play only one course for the rest of his life, which would it be?

“I would have loved to play St. Andrews,” he said. “That’s not going to happen. One course, for the rest of my life? Hmmm. To be honest about it, under these circumstances? I’m totally content playing my home course. Ocean View. I love where I am.”

I love where I am.

I asked Brian if he believed in life after death.

“I haven’t really thought much about it, but I believe I’m going to see my mom and dad and sister again, and my granny,” Brian said.

His parents shared a birthday, July 14. Brian was born July 15, 1967. It was a Saturday. The Open concluded that day. Roberto De Vicenzo won, at Hoylake, by two shots over Jack Nicklaus. A keeper.

“My birthday is on the second round of the next Open,” Brian told me. It’s at the Old Course. His favorite course. His favorite tournament.

Birthday candles typically come 60 to a box. He’ll have four to spare: 55 candles to mark his 55 years, plus one for good luck.

“I’m going to fight to stay alive so I can watch it on TV, but I can’t plan too far ahead,” he said. We made a deal: If I’m at the Open, and he can get to a phone, I’ll FaceTime him from the course. He laughed.

“I don’t want to die, I don’t want to leave those who are in this journey with me,” Brian said.

He prays, in his way. “You reach out to God when you can, where you can, whether it’s a church or a bathtub,” Brian said. He’s a bathtub guy, Bob Marley playing through the steam, literally. I asked if he had a go-to song.

“‘One Love,'” he said.

He half-sang the song’s famous refrain:

One love. One heart. Let’s get together and feel all right.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael.Bamberger@Golf.com.