Ed. note: The 2020 U.S. Open, now set for Sept. 17-20 at Winged Foot Golf Club, was originally slated for June 18-21. In a cap tip to the week that would have been, GOLF.com will be highlighting our national championship over the coming days, from its history, courses and legacy to its special ties to Father’s Day. In Part I, we looked back at Hale Irwin’s 1990 U.S. Open title. In Part II, we revisit The King and Cherry Hills.

*****

Who can forget that ’60 Open?

The National Open in the final year of the Eisenhower presidency, the Open when American golf said farewell to the staid fifties and put its arms around a new guy, a DIY American golfer who was unlike any winner who had come before him.

A Western U.S. Open, at Cherry Hills, out in Denver, altitude 5,300 feet. The best Open ever.

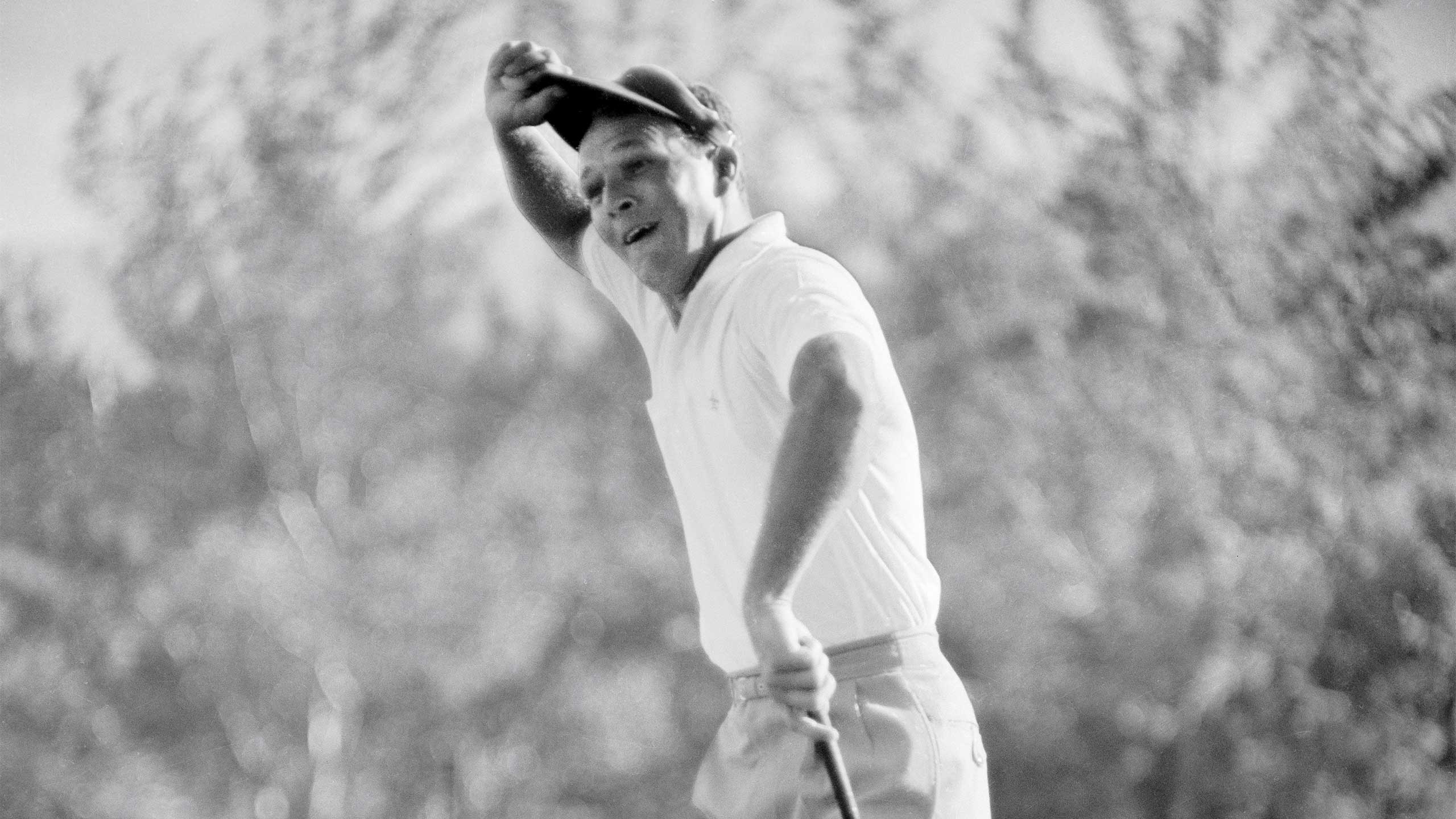

Remember how Arnie gibed with his writer buddies (Dan Jenkins, Bob Drum) at lunch on Saturday, in between the third and fourth rounds, then shot a closing 65 after driving the short par-4 1st? Golf has never had a more famous two-putt birdie or a winner who was easier to love. Arnold Palmer, his own self.

Remember how Arnie leap-frogged Ben Hogan, an old 47, in that last round, and how Hogan closed bogey, triple? All the Iceman needed was two pars for 280, which later became Palmer’s winning score. Remember how Arnold flung his visor into the crowd when he was done, even though the tournament wasn’t? Remember how the broadcasters pronounced the name of Hogan’s 20-year-old amateur playing partner? (Nick-LOUSE.) Remember Jack’s short pants and black shoes and white socks, and his own 72-hole total: 282? And what Hogan said to Jenkins? I played 36 holes today with a kid who could have won this Open by 10 shots if he’d known what he was doing. Remember all that?

Gosh, I do. Like it was yesterday. I was two months old.

No U.S. Open is more embedded in our subconscious than the 1960 Open at Cherry Hills. No National Open has grown more in stature since its playing, except the 1913 tournament, the year of Francis Ouimet. But the ’13 Open has been powered by Mark Frost, by Walt Disney Pictures, by Shia LaBeouf. By the Hollywood dream machine. The rise and rise of the ’60 U.S. Open was done without any marketing budget at all, and its stature has grown over the decades for one reason above all others: That’s when Arnold won his Open. He never won another.

You can’t even think of Arnold’s life without Cherry Hills. Without his win there, he wouldn’t have the standing he enjoys today, as the most important figure in the history of American golf.

No tournament meant more to Arnold than the U.S. Open because no tournament meant more to his father, Deacon, head professional at Latrobe Country Club. The whole father-son thing in American golf existed before that June day in 1960. (Bobby Jones and the Colonel.) But Arnold’s win was the start of Phase II, and suddenly there were a million daily-fee golfing fathers dreaming in green. First there was Arnie and Deacon. Later there was Tiger and Earl.

You could say it, back then: The U.S. Open was manly. Preparing for it, playing in it, taking it home. You did it for yourself, for dad, for country.

Palmer, then 29, won the 1960 U.S. Open with the most mesmerizing birdiefest in golf history, six in the first seven holes to start his fourth round. Over the next 20 years, in Palmer’s mind, there were 10 other Opens he could have or should have won. He spent his 50s, 60s, 70s and 80s obsessing about them. (He died in 2016 at 87.) Even though Palmer subsequently won all manner of other tournaments — including two British Opens and two Masters — he was never the same after the ’60 U.S. Open. “I lost the edge,” he once said. When he needed it most, he couldn’t find the gear that would let him close.

“Winning that first U.S. Open was an obsession,” Palmer told a small group of us one fall day at Latrobe. He was sitting at a round table in the club grill room. Lunch, the eating part, was over. He wasn’t holding court. He was speaking personally and from some deep place. “The first thing you want to do is win an Open. Then, after you win it, you have to stay aggressive, stay the way you were when you won it. And it’s difficult to do.”

Some months later, I relayed that scene to Nicklaus.

“Interesting comment,” Big Jack said. We were sitting in his office. “I make a similar comment every time I sit down in front of an audience and talk about that 1960 Open. I say the best thing that ever happened to me was not winning the U.S. Open in 1960. Because if I had won that Open, I would have been too smug or too self-confident and felt like however I had prepared, my game was ready. But I was growing into the game then. Arnold had already won two Masters. He was at the top of the game. He had the edge.”

Arnold had won the ’58 Masters. Two years later, he won the ’60 Masters. Two months after that came the win at Cherry Hills. Which meant that midway through 1960 there was only one person who could win four especially grand golf events — the Masters, the U.S. Open, the British Open and the PGA — in one year. If only professional golf had a tidy name for those four tournaments.

Kevin Drum is an expert on this whole broad subject. That is, the 1960 U.S. Open and its afterlife, the invention of the professional Grand Slam, the counting of professional majors, Jack’s 18 and Tiger’s 15 and Arnold’s eight. So is Kevin’s brother Bob Drum Jr. and their three siblings. They are the children of Bob Drum, Arnold’s Boswell. What Jenkins, born and raised on the Fort Worth Press, was to Hogan, Drum, born and raised on the Pittsburgh Press, was to Palmer. Kevin owns the Drum & Quill, a bar and restaurant in Pinehurst. Pinehurst is a nod to a lost time. So is the D&Q. So is this whole broad subject.

Arnold had already won two Masters. He was at the top of the game. He had the edge [at Cherry Hills].”

“When people look at the ’60 Open, they do it through the eyes of the modern sports fan, but you really can’t, because sports then was about storytelling,” Kevin Drum told me recently. He’s on to something. Modern sport is about numbers and analysis at the expense of blood and emotion. Kevin’s father was a storyteller. So was Jenkins. So was Arnold. Who has time for stories anymore? Well, now we do. That’s why everybody watched The Last Dance.

On many occasions, including in his 1999 autobiography, Arnold told two of the set pieces of his life, with Bob Drum on stage beside him.

The first is that Saturday-at-lunch conversation, on June 18, 1960. That’s when Palmer, in the telling and the retelling, said to Drum, “What if I shot 65? Two-eighty always wins the Open. What would that do?”

To which Drum said, “Two-eighty won’t do you a damn bit of good.”

The rest is I’ll-show-you history.

“What people can’t understand today is that this wasn’t ‘media member’ and athlete; these were two buddies — a sportswriter and a golfer,” Kevin says. “There was no antagonism there. My father was trying to spur Arnold on. He was a homer.” A subtle difference, and a critical one.

Arnold created the template of modern golf on that June day in 1960 by showing you could win a U.S. Open with length and pizzazz. Others followed suit: Nicklaus, Tom Watson, Ernie Els, Tiger Woods, Angel Cabrera, Rory McIlroy, Dustin Johnson, Brooks Koepka. You can put Phil Mickelson on the list with an asterisk, if you’re so inclined.

But here’s the part of Arnold’s win in ’60 that isn’t modern at all: the charm of the Drum–Palmer interaction. The setting of it. That something so big came out of something so small. A chat in the lunch room. A slashing drive minutes later. Capped off by a two-putt birdie that will live forever.

The other set piece to come of the 1960 U.S. Open was how it launched the professional, modern Grand Slam. When Gene Sarazen won the 1935 Masters, nobody said, “Well done, Geno. You’re the first guy to win the pro career Grand Slam!” Prior to 1960, and for a variety of reasons, no top player said, “I’m gonna organize my schedule around Augusta, the two Opens and the PGA.” Sam Snead played those four in 1946, but that was a one-off. Arnold did it for the first time in 1960, played in those four events in the same year, then did it 17 more times after that. Nicklaus played those four in the same year 36 times! Ever since 1960, the Grand Slam — just playing in the four Grand Slam events, golf’s majors — has become the game’s holy grail. Those Grand Slam events have defined Tiger’s public life and, for millions of us, become the focal point of more weekend days than we can count.

It all began, in Palmer’s telling, on a flight with Drum, after the 1960 U.S. Open and before the 1960 British Open at St. Andrews. They had been talking about Bobby Jones, who won the U.S. and British Opens and the U.S. and British Amateurs in 1930. Golf’s original Grand Slam. This is from page 233 of A Golfer’s Life, Arnold’s autobiography:

“Well,” I said casually over my drink, “why don’t we create a new Grand Slam?”

There’s often a drink in the Drum–Palmer stories. That was Palmer, quoting himself. Now he’s quoting Drum:

“What the hell are you talking about?” he muttered, though probably a little more colorfully than that.

Hmmm. There might be more to it than that. The other day, I was doing some electronic thumbing through old Pittsburgh Press sports sections from 1960. This is from the Sunday before the start of the U.S. Open at Cherry Hills. There’s an illustration of Arnold above the fold, with these words beside it:

ARNOLD PALMER

OUR DISTRICT HOPE,

5-TOURNEY WINNER

THIS YEAR, INCLUDING

MASTERS, TRYING

FOR GRAND SLAM—

OPEN, THEN BRITISH

OPEN AND PGA

There’s a Bob Drum story next to it. The date is June 12, 1960. I sent a photo of the caption to Kevin Drum, by text. His response was immediate: “Wow.”

Not that it really matters. It’s a better story if Arnold invented the professional Grand Slam, with the four tournaments we all know so well, and Drum ran with it. They were storytellers, the whole lot of ’em.

Arnold, trying to win the third leg of the professional Grand Slam, finished a shot behind the winner, Kel Nagle, at the ’60 Open Championship at St. Andrews. Drum was on the scene, there on his own dime. The Pittsburgh Press was begging him for copy, as the story goes.

There were four golfers in the field that week at Cherry Hills who would eventually get their names on the trophy alongside Arnold’s: Gene Littler, who won the ’61 Open; Jack Nicklaus, who won the first of his four Opens in ’62 over Palmer in a playoff at Oakmont; and Gary Player, who won it in ’65. And there was one 15-year-old kid watching them in person, who would get his name on the trophy three times before he was done: Hale Irwin.

“We had just moved to Boulder from southeastern Kansas, and I was caddying and playing at a public course across the street from the motel where we were staying while our house was being built,” Hale told me by phone recently. He’s 75 but his voice has not changed. “There was a local businessman named Les Fowler who loved golf, and he took me to Cherry Hills twice, once for a practice round, once for a tournament round. I saw Tommy Bolt, Dutch Harrison, Hogan, Arnold. I never saw so many new golf balls in all my life. Arnold had just won the Masters. He was hitting his stride.”

When Irwin won his first U.S. Open at Winged Foot in 1974, he and Arnold and Raymond Floyd and Gary Player were tied for the 36-hole lead. Golf, for Hale Irwin, was always the U.S. Open, Arnold Palmer, Cherry Hills, 1960, Mr. Fowler, teenage dreams.

“That ’60 Open branded me,” he said.

It branded Hale, branded Arnold, branded American golf. Bob Drum, his children, Tiger Woods, us. Hale Irwin wasn’t talking about wash-off tattoos here. This kind of branding requires a steaming hot iron. It’s forever.

Michael Bamberger welcomes your comments at Michael_Bamberger@golf.com.