It was amusing, when John A. Solheim, the chairman and CEO of Ping, made a casual Godfather reference in a recent interview. Solheim is not a student of the movie trilogy. He’s 75, an engineer by training, serious and quiet and not exactly immersed in pop culture, despite his new interest in skateboarding. (This year, at both the Solheim Cup and the Junior Solheim Cup, he gave each player and captain a skateboard he designed.) Solheim, presumably, has never settled a business problem by way of a poisoned cannoli, as Connie Corleone does in Godfather III. Still, when Solheim said he was in a “Godfather-type position,” it was a knowing nod.

Like the fictional Michael Corleone, Solheim runs a company founded by his European-born father. (Karsten Solheim was born in Norway in 1911 and died in Phoenix in 2000.) The Corleones — Vito, followed by Michael and finally Michael’s nephew Vincent — face a range of complicated succession issues, financial and emotional, as the Solheims have in real life.

But there the broad similarities end. The Corleone family business was gambling and extortion. The family was based in New York and operated out of an opulent suburban mansion. The Solheims make golf clubs in a series of nondescript, sunbaked buildings off I-17 in Phoenix, the worldwide headquarters of Karsten Manufacturing (a telling name). As the don in the third generation, Vincent turned out to be a hothead, a renegade — and a disaster. John Karsten Solheim, anointed by his father, John A., as his successor, is steeped in the practices that made Ping Ping.

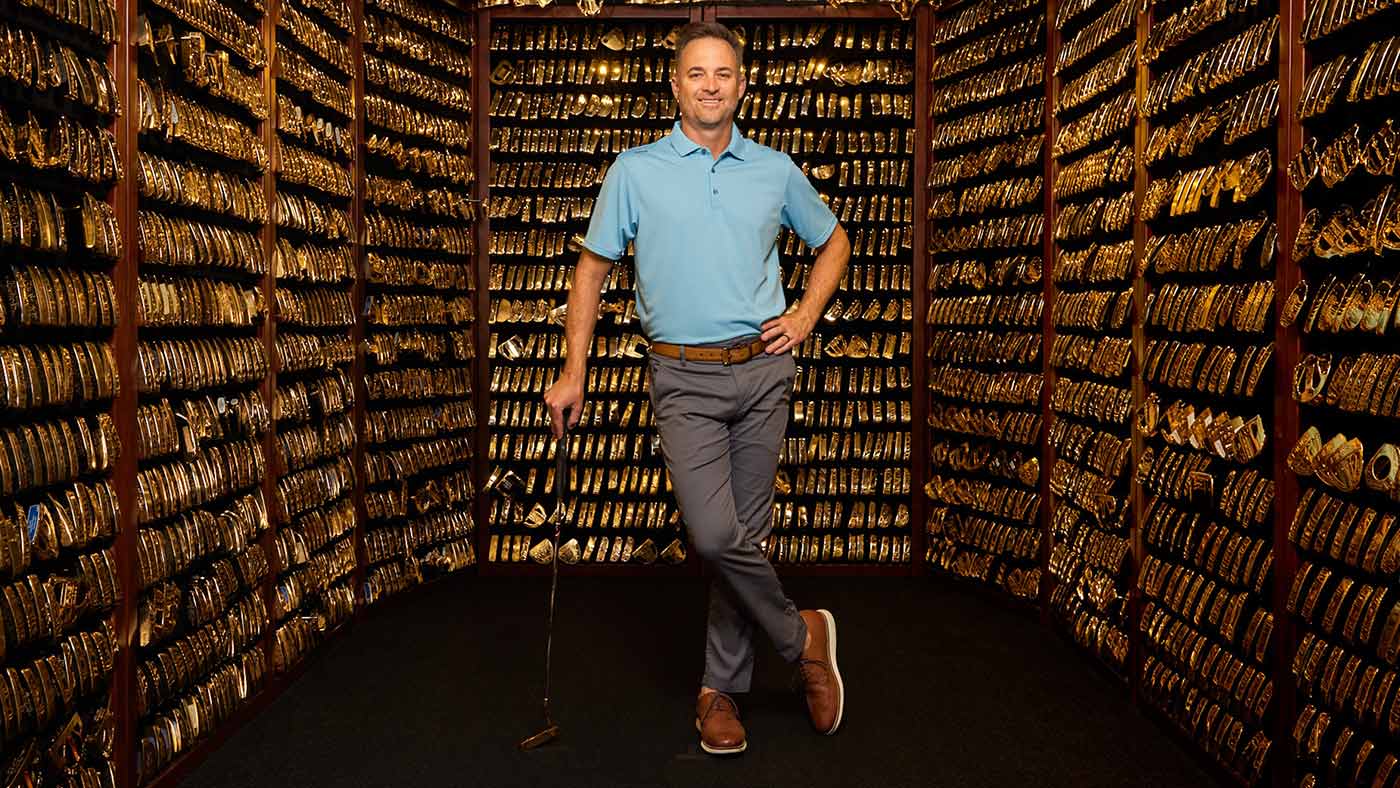

John K. has been the Ping president for five years already. In due course, he’ll assume his father’s titles (chairman and CEO) and responsibilities. He’s been training for the job all his life, really. He’s 47.

“It’s the third generation that loses a business, generally,” John K. Solheim said recently. He’s a businessman and an engineer, and he has a light touch. “If you get to the fourth generation, you have a legacy business.” The Ford Motor Company, for example.

In Succession, the HBO show about a media mogul and his heirs, there’s a reference to investing with a long-term view — 1,000 years. One summer, when the younger John Solheim was in college, he was his grandfather’s gofer. He saw first-hand that Karsten didn’t have a 1,000-year horizon. “He had a mindset of work on today, that today’s problems are big enough, and don’t punt things down the road,” Solheim said. “Deal with today’s problems today.”

Listening to the father and son, in separate interviews, describe the company’s past, present and future, it’s easy to reach this bold conclusion: The company’s next 30 years will look largely like its last 30. Club design rooted in engineering. Marketing campaigns that make the L.L.Bean catalog look flashy. Black as the go-to paint for drivers, fairway woods and hybrids. Bubba Watson showing up at the Masters each April wearing a Ping hat, carrying a Ping bag and playing Ping clubs.

It’s the third generation that loses a business, generally. If you get to the fourth generation, you have a legacy business.

“I never met Karsten — I wish I did — but for me John Solheim is like a father figure,” Bubba said recently. That is, John A. Solheim, the youngest of Karsten’s three sons. For a while, Bubba had a gift for getting himself in trouble with his mouth, sometimes with hot mics, sometimes with players, once with his own caddie. John A., in his mild-mannered way, got in Bubba’s face. “He came up to me at a tournament and said, ‘We can’t act this way. Forget golf, forget my company. As people, we can’t act this way.’” The paternalistic chairman.

Bubba got his first half set of Pings — left-handed, stamped with odd numbers — as a Christmas gift from his parents when he was eight. Bubba’s mother and father, living on the Florida panhandle, were not steeped in golf. But there was a local pro, Hiram Cook, who played Ping because he was lefty and the local Ping rep went out of his way to supply Cook with clubs for his own use. Bubba’s parents took their cues from Hiram Cook. The Ping reps took their cues from Karsten Solheim. Karsten’s marketing method was elementary: Take care of your base. That is, on-the-ground club pros and everyday golfers who know that the value of a golf club ultimately comes down to a single thing, which is (of course) its performance.

“We don’t blow it out the door with our marketing campaigns,” John K. said recently. “We let our equipment do the talking.” Bubba is likely the loudest and boldest person associated with Ping. He’s a de facto Ping marketing executive.

“I called John K. and said, ‘Y’all want me. I want you. Let’s not argue anymore. How about a lifetime deal?’” Bubba said recently. “John was in the first year as the president. He said, ‘I gotta talk to my dad about this one.’”

Son talked to father. Eventually, Bubba, who is 42, got his contract for life. You can be sure there are no crazy numbers in it. Ping doesn’t do crazy. It’s really two contracts in one: one covering Bubba’s remaining years as an active player, the other for when he’s sitting on the porch rocker. But without John K.’s endorsement of it, the deal never would have happened. The father and son lean on one another. They’re partners.

That’s not a given, not in any multigenerational family business. John A., the older living Solheim, said he was determined to learn from his father, in good times and in more challenging times too.

“The transition between Dad and I was not easy,” John A. said. “Dad would not discuss anything that had to do with him being gone. He didn’t want things to change. We were moving to new things, and he was hanging on. I understand what he was doing and why, but I didn’t want my son to go through that. I’ve been letting him run.”

John K. thought he was ready to start running Ping a decade ago. His father had another idea: Go to Japan, where Ping had been struggling. When John K. arrived with his family — his wife and their four kids — Ping had 1 percent of the market share, he said. They stayed for close to four years. By last year, that number was 17 percent. The breakthrough, as Solheim explained it, was understanding the Japanese golfer.

“The American golfer picks up a club in a shop and waggles it,” he said. “The Japanese golfer picks up a club and brings it right to his face.” So John K. started paying more attention to the finish on Ping’s clubs, their ferrules, how they were wrapped. Cosmetics! Karsten might not have approved. But you can’t get to performance if you can’t get a golfer to try your club.

There are guitars on the wall of John K.’s office and a Whoop health-monitoring strap around his upper arm. The junior Solheim is a triathlete and musician. One of the highlights for him at this year’s Solheim Cup was a Gwen Stefani concert, sponsored by Ping. (He didn’t meet her and didn’t try. That’s so Solheim.) John A. says his son has his father’s ear, that he can hear the many different and telling sounds that come when a golf ball and a clubface meet. Those insights can make or break a club.

The Ping name comes from the pinging sound Karsten’s first design, the 1A putter, made with its hollow midsection. John A. would stuff a small piece of rubber tire in the putter’s cavity to deaden the sound. Fathers and sons.

As a family company gets older and larger and more established, and the family behind it becomes older and larger and more established, conflict arises. A boss makes hard decisions. People, often blood relatives, can get hurt or offended. The attitude has to be, the senior Solheim says, that “taking care of the business also takes care of the family.” When he becomes the boss, John K. Solheim, the third Solheim chairman, may discover that for himself. Or not.

He remembers driving his grandfather in a golf cart on the Karsten Manufacturing campus on the rare times Karsten permitted it and “holding on for dear life” the rest of the time. You can see it: Karsten behind the wheel, his little white goatee blowing in the hot wind, knowing there is not enough time in the day to get everything done. The grandson watching and learning.

Maybe the Solheims do do crazy, just a little, and in their own inimitable way.